By Deborah Espinosa and Patrick Gallagher, USAID’s Land Technology Solutions Program

Persistent and pervasive gender inequality is a global development challenge that constrains economic growth, educational opportunities, and health outcomes. It jeopardizes food security and undermines poverty reduction strategies. The world over, some formal and many informal laws and customs operate to hinder women’s empowerment and thus their full potential as agents of economic and social change.

Arguably, in no sector are gender disparities so prevalent and disempowering to women as in the land and property rights sector. For women, documented land rights can confer direct economic benefits and lead to greater autonomy, increased bargaining power within their communities and households, and enhanced resilience. Worldwide evidence suggests that when women enjoy secure rights to land, their control over household income increases.[1]

In much of the world, however, the ownership and control of land is a source of power, prestige, and profit. Not surprisingly then, women’s ownership and control over land is almost always constrained by entrenched traditions and practices that limit women’s participation in public life, even if formal laws recognizing women’s land rights are in place.

Importantly, USAID’s new and innovative tool for documenting land rights has proved impactful in reversing these trends. USAID’s Mobile Application to Secure Tenure (MAST) has worked to reduce gender equality and promote women’s empowerment in communities where it has been implemented. MAST is a suite of easy-to-use tools and methods that help communities efficiently, transparently and affordably map and document their land and resource rights. MAST combines a mobile application with a robust data management platform to capture and manage land information, including names and photographs of people using and occupying land, details about land used, and information regarding an occupant’s claim to the land.

Working with local governments, customary leaders, and civil society organizations, USAID is leveraging MAST to recognize and record both women and men’s rights to rural land, with positive women’s empowerment outcomes in Tanzania and Zambia.

In Tanzania, for example, although Tanzanian women comprise 50 percent of the population and provide 80 percent of total agricultural labor (a sector which employs 77 percent of Tanzanians), country data indicates that only 27 percent of women are landowners.[2] The country ranks 119th (out of 189) on the UNDP’s 2013 Gender Inequality Index. In 2018, Tanzania’s ranking has even fallen since its 2013 ranking of 130th. [3] [4]A key reason cited for Tanzania’s drop in the rankings is the persistence of gender inequalities in access to and control over land and other financial resources, and the additional burden that poverty places on Tanzanian women.[5] Another gender disparity in Tanzania is the low proportion of women in decision-making positions at regional and local government levels.[6]

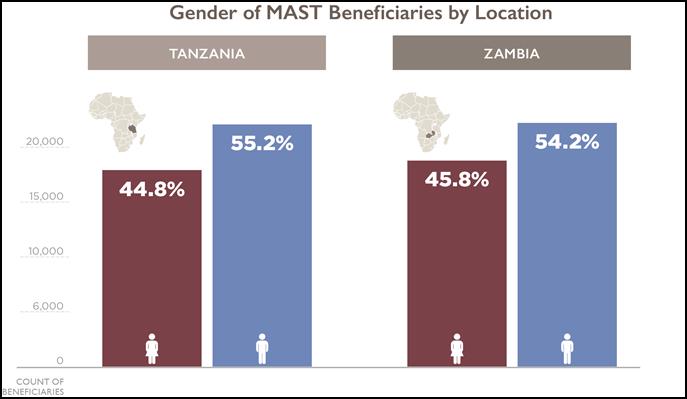

And yet, four years into USAID’s MAST-based Land Tenure Assistance (LTA) Program, almost 45 percent of project beneficiaries receiving land certificates are women (see Figure 1). Similarly, under USAID’s Tenure and Global Climate Change program in Zambia, two civil society organizations, Chipata District Land Alliance (CPLA) and Petauke District Land Alliance (PDLA), used MAST to also register about 45 percent of customary land in the names of women in a country with similar traditional constraints on women.

In both of these countries, MAST’s approach has been critical in promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment in the land sector. MAST includes on-the-ground trainings, using inclusive and participatory approaches to build capacity of communities to document, manage information about, and understand their land and resource rights. The MAST approach operates transparently, encourages full participation of community members, and increases the understanding of land rights of all beneficiaries, particularly women’s rights.

To hear directly from Zambian women on their experiences obtaining land certificates, see the USAID video, In My Own Name, Empowering Women Through Secure Land Rights.

What Does the Data Say?

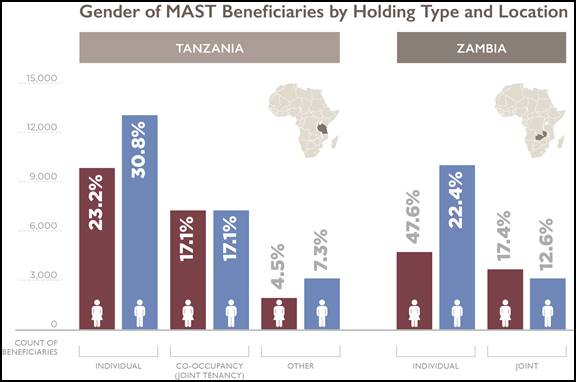

A gender analysis of data on individual versus collective landholdings provides further insight useful for future programming. In both Tanzania, and Zambia, more men hold land individually, while more women hold land jointly or in co-tenancy arrangements. This finding is backed by research indicating that female ownership of land is generally held together with husbands, whereas men are more likely to be sole owners of land.[7]

Despite that, men currently represent a higher proportion of individual landowners, the implementation of MAST has proven effective in promoting gender equality and empowering women by providing a technology coupled with an inclusive approach for recognizing and documenting land rights. In Zambia, land documentation had positive impact on household perceptions of improved tenure security,[8] and in Tanzania, there was an11% increase in respondents who felt that disputes over land will improve in the next year.[9]

[1] Meinzin-Dick, et al. 2017. “Women’s Land Rights As A Pathway to Poverty Reduction: Framework and Review of Available Evidence, in Agricultural Systems, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308521X1730505X.

[2] FAO. 2014. Gender Inequalities in Rural Employment in Tanzania Mainland An Overview.

[3] UNDP. 2018. Human Development Report.

[4] UNDP. 2018. Human Development Report.

[5] UNDP. 2018. Tanzanian Human Development Report 2017: Social Policy in the Context of Economic Transformation. Tanzanian women spend 13.6 percent of their time per day on unpaid care work compared to 3.6 percent for their male counterparts. Id. As a consequence, women’s availability for income-generating activities is reduced, to the detriment of themselves and the household and local economies.

[6] Id.

[7] Land Alliance and ODI. (2017). “Prindex Analytical Report.”

[8] USAID. 2018. USAID Tenure and Global Climate Change Evaluation Report.

[9] USAID. 2017. Baseline Report: Impact Evaluation of the Feed the Future Tanzania Land Tenure Assistance Activity.