The following is an excerpt from an article posted on Thomson Reuters Foundation PLACE. Follow the link below for the full article.

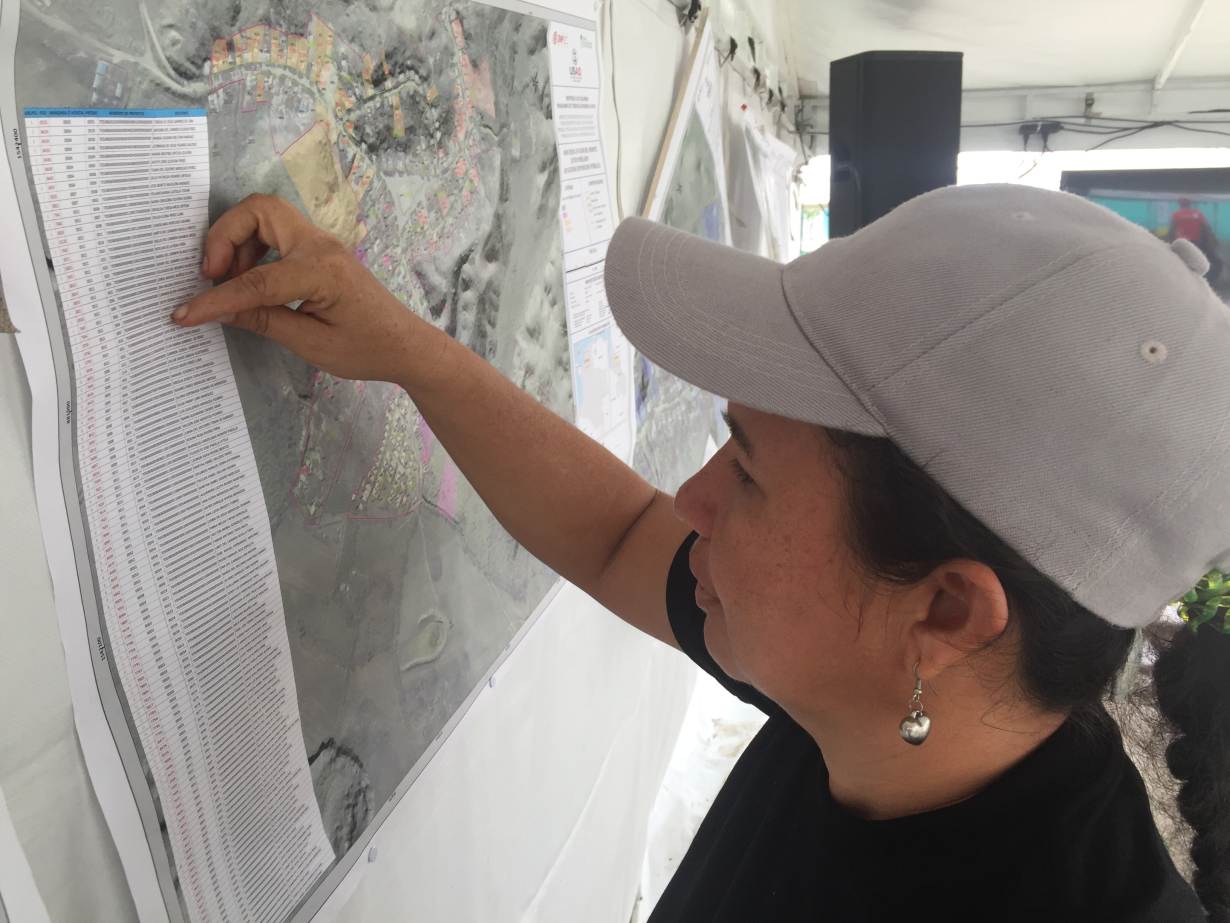

OVEJAS, Colombia, June 4 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – Forced to flee her home to escape violence during Colombia’s half-century civil war, farmer Diana Vitola has been waiting decades to receive a formal document proving she is the lawful owner of a small plot of land.

Living in the former war-torn municipality of Ovejas in northern Colombia, Vitola belongs to a farming community set to receive nearly 3,000 land and property titles, making this the first area where most land is formalized.

“We’ve been waiting years for this,” said 45-year-old Vitola, who grows maize and cassava.

“As a woman, it’s really exciting. Before women were marginalized. Now we can appear somewhere on a document. We feel important, that we have rights.”

“For the past 18 months, government officials have been visiting farms and thatched adobe homes in Ovejas on foot measuring, surveying and identifying plots of land.

Farmers now have the chance to register their property with the national land registry and receive formal titles for free.

CORNERSTONE OF PEACE

Granting land titles is part of government efforts to promote rural development as set out in the 2016 peace deal signed with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebels.

Unequal land distribution was a key reason why the FARC took up arms in 1964 as a Marxist-inspired agrarian movement that fought to defend the rights of landless peasants.

The peace accord pledges to address unequal land ownership and foster development in neglected rural areas hit hard by violence.

The government aims to formalize 7 million hectares of land, of which so far nearly a quarter have been titled, according to the University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.

“The land reform package is part of the attempt by the state to deliver to small farmers what has historically been denied to them, which is access to land and a dignified existence in the countryside,” said David Huey, Kroc Institute representative in Colombia.

Formal land titles will also help farmers to get access to government programs and credit, he said.

For villager Albeiro Rivera, who was also displaced by Colombia’s conflict, getting a property title to the home he grew up in and informally inherited from his father brings financial and legal security and allows him to get a bank loan.

“During the conflict, getting a land title wasn’t a priority. The priority then was to survive,” said 37-year-old Rivera.

“Having the property title means it is ours, it belongs to me and my wife. It’s a huge step. It’s now worth more and nobody can take it away from me. It would’ve been too expensive to have registered the property myself,” Rivera said.

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which is partly funding the pilot project in Ovejas, said it hopes to roll out similar initiatives over the next couple of months in other regions.

“The problem here is the lack of clarity about what land belongs to whom,” said Larry Sacks, USAID’s mission director in Colombia.

“Without the clear land rights it’s considerably more difficult to create the conditions that you need to transform rural areas to help licit markets flourish, to trigger private investment and spark economic growth,” he added.

FEW LAND TITLES

With property titles, the villagers of Ovejas are rather the exception than the rule.

Across rural Colombia, six out of 10 plots of land do not have a formal title or are not registered, according to USAID.

Granting land titles in Ovejas is relatively easy because no one disputes ownership of the plots.

Yet sorting out tenure is far harder in other parts of Colombia where land was seized by paramilitary forces, rebel groups or drug traffickers, with farmers often pressured by armed groups to sell out at cut-rate prices.

Attempts to restore landownership started during the previous government of Juan Manuel Santos, which launched a program in 2011 to return millions of hectares of stolen or abandoned land to their rightful owners.

The government then estimated 6.5 to 10 million hectares of land – up to 15% of Colombian territory – had been abandoned or illegally acquired.

Read the full story