This blog was originally published on Agrilinks.

By Chloe Bass

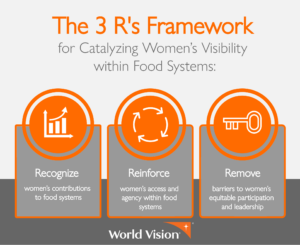

A discussion on sustainable food systems would be incomplete without attention to women’s contributions; yet too often they are a mere afterthought for policymakers, private sector strategists and international development program designers. While they may not be recognized, female producers, entrepreneurs and consumers make important contributions within food supply chains, food environments and food consumption domains of the world’s local food systems. Promoting women’s equitable engagement across all domains of a food system leads to increased food security, business profitability and country business profitability and country gross domestic product (GDP). As development practitioners, we must be intentional about including women and promoting their empowerment within all domains of the food system. The “3 Rs” Framework provides a useful lens for women’s integration.

R1: Recognize Women’s Roles in Food Systems

In many countries and contexts, women’s roles and contributions as producers, processors and consumers are underappreciated, and not formally recognized by policymakers and program designers. This can lead to exclusion from important training, planning, financing, decision-making and leadership roles. This can also have negative psychosocial effects on women. Across all food systems domains, when designing programming, it is critical that all actors — government, private sector, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and communities — recognize the roles women play. This means placing a premium on generating data, documenting women’s roles and communicating evidence of their impact within food systems. Women should be central to developing and sharing these narratives.

R2: Reinforce Women’s Access and Agency within Food Systems

For women to be economically empowered, they need to have both access and agency. Within food systems, this means having access to assets, capital, information and group membership. Agency is equally critical, as women need to have power to make decisions, to act on them and to be supported in the exercise of their agency. Reinforcing women’s access and agency are critical to empowerment and inclusive food systems.

For example, when considering ways to strengthen a local food environment (physical access to food, quality and presentation of food), governments can enforce existing laws and policies that support women’s equality, mobility and safety and ensure that accountability measures are in place, and NGOs can ensure that they design and implement programs that promote women’s participation and leadership.

It is also critical to reinforce women’s participation, promotion and leadership at multiple levels: at an individual level working directly with women; within households to promote female power; within communities and community institutions; within food and agriculture associations to levels of leadership and influence; and systemically through laws, policies and procedures. When this is done, it will benefit the whole system.

R3: Remove Barriers to Women’s Equitable Participation and Leadership

Reinforcing women’s current levels and types of participation within a local food system addresses questions of scale potential. These must be complemented by actions designed to increase the scope of women’s participation, including recognizing and addressing the most critical barriers to effective engagement for equitable participation and leadership. Within food systems, common barriers include:

- Inequitable access to knowledge, influential networks, technology and training.

- Inequitable laws and social norms around women’s ownership of land and other assets, women’s mobility, unpaid care work and household food consumption practices.

- Prevalence of gender-based violence against women.

- Blockages by gatekeepers.

- Inequitable pay for women (impacting income available for food expenditures).

- Barriers to women’s voice, decision-making and leadership.

- Lack of women’s representation.

As this list is not exhaustive, conducting inclusive market assessments, gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) analyses or other surveys/formative research in the beginning of programming assists in identifying the critical barriers for women, especially as the intersection of varying points of marginalization and vulnerability (age, ethnicity, religion, marital status and sexual orientation) can compound upon one another. Once identified, the proper interventions can be set in place to remove the relevant barriers.

For example, in the domain of consumption, agribusinesses can create relevant products and marketing targeting women as a viable market segment and implement women in leadership pipelines and safe work standards. Private sector actors can also ensure they have equitable hiring, remuneration and mentorship practices. Likewise, industry associations and cooperatives serve a critical function in mentoring women historically excluded from enterprise ownership and contributing to agribusinesses maintaining the competitive edge. These organizations provide opportunities where women can be mentored through invaluable connections with people who are influential, knowledgeable and experienced in their respective markets. Continual learning to upgrade an enterprise while establishing relationships with gatekeepers of a market segment through association mentorship helps bridge the gap for women to lead resilient agribusinesses.

World Vision Example: the 3 Rs in Practice

In its USAID-funded Nobo Jatra program in Bangladesh, World Vision uses multiple approaches to address the drivers of food insecurity. To promote R1: Recognition, the program worked with 200,000 households and the local, regional and national government structures to promote improved nutrition in a sustainable way by recognizing the important role mothers and grandmothers have in food preparation, and working with them to better understand the health and nutritional needs of women of reproductive age and infants and young children. To promote R2: Reinforce, using our graduation model, that provided up to $188 in cash grants for start-up capital, World Vision coached/mentored 21,000 women in literacy, numeracy, financial management and skills needs for various trades, many of them within the local food system. In this area in southwest Bangladesh, previously only 15% of women participated in paid employment. On average, they earn $54 to $75 a month, a sizable amount in this area.

To Remove Barriers (R3) and address sociocultural drivers and inequitable gender norms in the production and nutrition domains, World Vision promoted more positive household relationships that improved the status of women in and out of homes. Men who think that women should be consulted on household budgeting and purchases rose from 43.3% to 79.6%, while those who think men and women should share household tasks rose from 8.3% to 53.5%. The project increased leadership opportunities for women to participate within influential community networks: food producer groups; village development committees; disaster management committees; water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) committees; and community clinic support groups (R1, R2 and R3).

Call to Action

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating the benefits of including women in economies and food systems. The 3 Rs — recognize, reinforce and remove barriers — offer a practical lens to assist in the development of more equitable, sustainable food systems that benefit communities worldwide. Repeatedly, data show that including women’s involvement yields better household outcomes, increased idea and profitability and lower risk for businesses, and more representative government budgets and policies. We encourage all development stakeholders to examine where each might employ the 3 Rs in your food systems programming and how you might affirm other stakeholders who are employing these approaches. When food systems are more inclusive of women, we will see the rewards.