Volunteer community leaders are building trust and hope among rural citizens and spreading knowledge about land rights

Every morning Luz Estela Velandia wakes up to jog. A spry woman in her late sixties, she is vivacious as ever. She has hundreds of medals from a career in athletics, but these days jogging is as much about her health as it is about her community.

While roosters squawk, she runs by neighboring farms and thinks about her neighbors. She considers a variety of land conflicts common in her village that have split families and divided neighbors. In one family, two brothers are fighting over who gets what land after their father passed away. Over there, a family has built a shack and occupied an empty space next to the dirt road. On another plot of land, which was granted to them by the government in the 90s, some 17 families are living and farming under one single land title, and none can agree on anything.

La Luna is located in the municipality of Fuentedeoro where 6 out of 10 parcels are informally owned. Historically, Colombian land owners are responsible for titling and registering their properties with the state, but due to costs, complicated land laws, and the absence of government services in rural areas, informal land markets thrive.

Some 60% of the properties in Fuentedeoro lack a registered land title. USAID is supporting government to update the land cadaster and deliver land titles.

In La Luna the majority of people do not have a registered property title, and the conflicts seem to be endless. The subject of land tenure has become one of Velandia’s passions. Over the last year, she has learned more about property issues facing her neighbors than ever before. So, when she finds time between jogging, crafting, and leading La Luna’s Community Action Committee, she is teaching people about land rights and how property is titled and administered under Colombia’s arcane laws. Like hundreds of other rural municipalities in Colombia, Fuentedeoro has a decades-long history of violence, tragedy, and the struggle for land rights that has shaped its collective psyche. Under these conditions, reaching the community is not always simple.

“Fuentedeoro is the kind of place where people won’t open the door to strangers or give out personal information. People do not feel safe, and with the recent presidential elections, there is still a lot of uncertainty in the air.

Velandia’s job is to allay some of these fears and assure her neighbors that the government’s objective to increase land tenure security in rural areas is a legitimate, long-term commitment. For the last five years, pressure to title property and strengthen the formal land market has been percolating in the municipality thanks in part to USAID-funded programming to establish a Municipal Land Office and to examine the titling of properties of families living on many parcels under one land title.

In 2021, Velandia became one of dozens of community outreach volunteers raising awareness about land rights, the benefits of land titling, and the ongoing land formalization campaign in Fuentedeoro. As a volunteer, she received training in land formalization issues and social issues with supporting a culture of formal land ownership. The training, which is provided under the USAID funded Land for Prosperity program, includes a kit of teaching tools designed to simplify concepts.

“Before this, I knew nothing about land administration and Colombia’s land laws,” she admits.

Volunteers and land titling specialists at work in Fuentedeoro, Meta in 2022.

Massive Land Titling

Fuentedeoro is one of 11 initiatives funded by USAID and supported by Colombia’s land entities, including the National Land Agency. In total, the Fuentedeoro parcel sweep or barrido predial, as it is commonly referred to in town, aims to net over 2,000 rural property titles for landowners, some of whom have waited 40 years for a registered property title.

Just as important, the campaign will update the municipality’s rural cadaster for more than 6,000 parcels. The cadaster, which was last updated in 2006, is a master chart of all rural properties. Not only have properties changed owners since then, but land has been subdivided among families or sold to newcomers.

This methodology was created and refined by USAID and the Colombian government following the 2016 Peace Accords. Parcel sweeps streamline the collection and processing of property information in order to reduce costs and provide land agencies with integrated and reliable land data. Until recently, neither local nor national government agencies had complete control over this information.

With USAID funding and technical leadership, for the first time ever, Colombia’s three major land administration agencies are cooperating, sharing information, and supporting land titling campaigns to reach a goal of updating more than 100,000 parcels and delivering up to 40,000 land titles over the next five years.

Playing Games

Large land formalization campaigns rely heavily on social workers and outreach, and community liaisons like Luz Estela Velandia are one of the most effective ways to ensure participation. Trusted and motivated neighbors can fill the spaces where the government has been absent. Many in Fuentedeoro have long distrusted the government and believe land titling is just a ploy to take their land away. To overcome this information barrier, Velandia mobilizes her neighbors through neighborhood Whatsapp groups, where she can quickly reach 150 families living in her village.

Large land formalization campaigns rely heavily on social workers and outreach, and community liaisons like Luz Estela Velandia are one of the most effective ways to ensure participation. Trusted and motivated neighbors can fill the spaces where the government has been absent. Many in Fuentedeoro have long distrusted the government and believe land titling is just a ploy to take their land away. To overcome this information barrier, Velandia mobilizes her neighbors through neighborhood Whatsapp groups, where she can quickly reach 150 families living in her village.

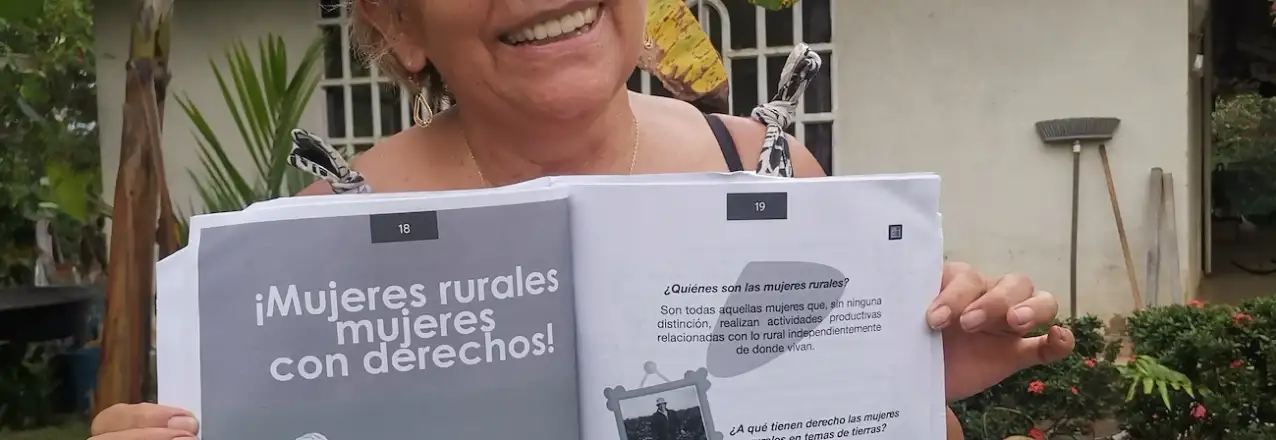

In the groups, she advertises outreach meetings where she then uses the teaching kit, which includes flip charts, games, and puzzles to improve recognition of complicated land topics. The memory matching game, which requires participants to match land administration concepts, is a crowd favorite.

“The kit is didactic and participatory,” she explains. “It has to be this way, because the subject matter is complex, especially for people who may not have a very high level of education.” The teaching resources are also an attraction. In her first outreach event, 60 people came to learn about the land titling.

“One of the first things we learn together is the difference between a registered land title and a carta-venta,” she says. The carta-venta is a notarized receipt typical of a land transaction in rural Colombia. Over three months, she has reached over 100 people with the community crash course in land rights.

Velandia is not always successful. One group of families living on a collective land parcel say they do not want to participate in the massive land titling campaign, which is free of charge. Over the last five years, the families have invested thousands of dollars in a lawyer who claims he will individually title their properties. Though the government cannot force people to title their land, the campaign still updates property information in the rural cadaster.

Benefits of a formal land market

“I tell people that, yes, they will have to pay property taxes, but a land title can also bring them government subsidies, programs, and better services. I tell them a land title represents their rights. And I tell them that women have the same rights as men to appear on a property title as a man.”

These campaigns to title thousands of properties at once form part of the government strategy to move away from a demand-driven land administration policy to one in which the government assumes the cost of first-time formalization. By doing so, it will alleviate major time and cost burdens that prevent most low-income rural landholders from seeking a valid title. Once a property is registered, future title transfers will be much less time and cost intensive. The Fuentedeoro campaign started in October 2021 and will take place over a period of 12-18 months.

For now, community volunteers like Velandia are becoming the government’s most important allies to increase public participation.

The Land for Prosperity Activity is raising awareness about land formalization among citizens and partnering with academic and educational institutions to prepare the next generations of Colombians for a culture of formal land ownership.

“The key is personalizing all these relationships. We spend time together and have coffee and teatime and we can be honest about what is happening in our lives. Especially for the women, I give the program more credibility.”

Cross posted from Land for Prosperity Exposure site