Balancing successful wildlife protection and expanding human populations leads to reduced human-wildlife conflict in Zambia’s North Luangwa Ecosystem

As the global community wakes up to the deepening biodiversity crisis, many of Africa’s wild spaces are under threat, not from guns and poachers, but from the shovels and agricultural fields of smallholder farmers trying to make a living. While a family growing corn or cotton may seem less ominous than a man holding a gun and poached ivory, the negative impact on wildlife can be equally devastating.

Each year, rural communities broaden their search for increasingly-scarce arable land and encroach on wildlife habitat. While this move makes sense from the farmer’s standpoint, this expansion intensifies human-wildlife conflict, often resulting in deadly human-animal confrontation, crop destruction, and attacks on livestock. Forests and wetlands converted to fields may never revert back to habitat for elephants, leopards, lions, antelope, and other key species that help to sustain a balanced ecosystem. This loss of habitat and change of land use represents a generational change.

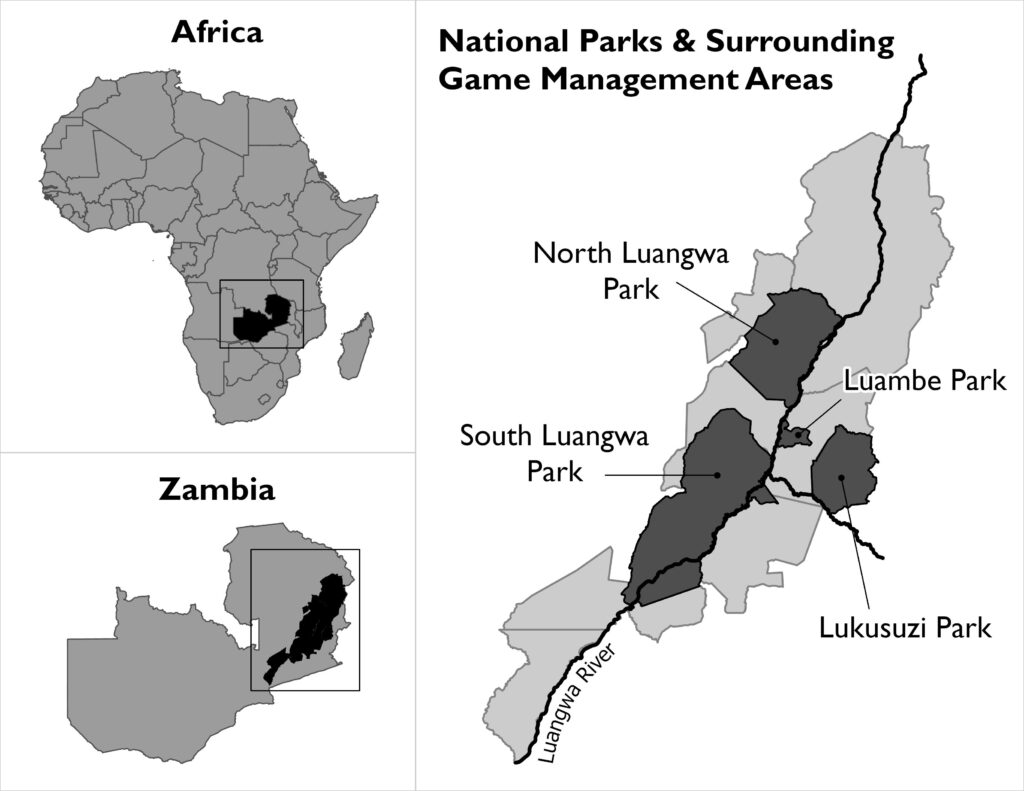

To combat this growing trend, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and Frankfurt Zoological Society are partnering with local communities in the North Luangwa Ecosystem of Zambia to strengthen the land and resource rights of rural communities, in the hopes of improving long-term land use planning to prevent encroachment into wildlife habitats, protect individuals’ rights to their land, and support sustainable livelihoods.

The Luangwa Valley is the oldest section of the Great Rift valley, a landscape along Africa’s largest undammed river that blooms with the rains from November to March. At the heart of the valley are the North and South Luangwa National Parks, bordered by an escarpment on one side and the Luangwa River on the other. The area’s abundant elephant populations were decimated by poaching in the 1980s, and rhinos were poached to local extinction. Since that time, large investments have helped to return a healthy population of elephants and other species to the area.

The valley is also home to 70,000 people and over 4,500 settlements in five customary chiefdoms, a population that has tripled over the past forty years. The chiefdoms are located in areas known as Game Management Areas, buffer zones to the national parks designed with the dual objectives that both wildlife and communities flourish. But these buffers are being pressured both by increasing wildlife populations, due in part to successful conservation efforts, and farmers. Each year, farmers prepare new tracts for agriculture, cutting deeper into habitats, within the current ranges and prime habitats of elephants and hippos, as well as predators.

The valley is also home to 70,000 people and over 4,500 settlements in five customary chiefdoms, a population that has tripled over the past forty years. The chiefdoms are located in areas known as Game Management Areas, buffer zones to the national parks designed with the dual objectives that both wildlife and communities flourish. But these buffers are being pressured both by increasing wildlife populations, due in part to successful conservation efforts, and farmers. Each year, farmers prepare new tracts for agriculture, cutting deeper into habitats, within the current ranges and prime habitats of elephants and hippos, as well as predators.

Clarifying Land Rights and Usage

In Zambia’s customary settings, land ownership and conflicts are managed by chiefs and village headpersons, who typically allocate property by telling families that they can expand their plot from one edge to a tree some distance away. Unfortunately, these verbal records are easily forgotten and open to interpretation. In addition, headpersons are often open to influence and bias, and as a result may allow some farmers with connections or influence to expand farmland outside of planned agricultural areas as fertility declines on well-established fields.

“We spend most of our time resolving conflicts between households every agriculture season. It is tiring. I know generally where people have lived, but I am asked to make decisions with very little information,” remarks a headperson from Kafoteka Village Action Group in Chifunda Chiefdom.

Working with chiefs and local community resource management groups, USAID and Frankfurt Zoological Society are supporting land use planning and documentation of households’ land and implementation of inclusive and transparent land governance across these landscapes of hundreds of thousands of hectares. With more secure land rights, communities can better manage their land and designate areas for agricultural expansion that do not create conflict with wildlife.

With USAID support, community enumerators are now documenting customary land with GPS-enabled smartphones and large-scale maps. After holding sensitization sessions with communities about the customary land documentation process, enumerators walk each and every field boundary and record the names of landholders and potential beneficiaries, paying special attention to the rights of women and children. This leads to the production of a community map for validation, which is ultimately approved by the community and signed by the chief. The chief then distributes land documents, proving an individual’s rights to a particular piece of land, which not only decreases conflict but can lead to better long-term land use planning.

Preparing for the future is an urgent task. Using these community maps, the traditional leaders and community members then develop long-term land use plans that cater to human and wildlife needs.

“We know the elephants will not respect the boundaries of our fields or our land certificates. But if we can use land planning to decide where we should not allocate new fields, we may be able to live in peace,” explains Chief Chikwa. “With FZS [Frankfurt Zoological Society], we’ve done land use plans and identified the areas for conservation, agriculture, and expansion. These household field maps will feed into the bigger plan.”

The future of Zambia’s wildlife landscapes and those around the world will be determined by what happens in the multi-use zones surrounding national parks. Mapping customary land holdings and engaging in long-term land use planning is critical to reducing human-wildlife conflict. It can help communities strategically decide where to expand in order to reduce encroachment on animals’ habitats, and better balance community needs and conservation imperatives. Local communities must be active participants in this effort, helping to both secure their rights and ensure that Zambia’s rich biodiversity is protected for the next generation.