The Challenge

Mozambique has a complex history of land tenure that dates back to colonial times.1 Both during and after Portuguese rule, private companies acquired rights to large tracts of land that communities have historically used and governed. Conflicts surrounding these company lands, including the country’s vast plantation forests and the land upon which they stand, have increased over the past 10 years. Though all land in Mozambique is officially owned by the state (as is common in most of sub-Saharan Africa), the country recognizes the land rights of communities and individuals acquired through customary governance systems and good faith occupancy. However, over 75 percent of rural land remains unregistered and under informal tenure arrangements, leaving millions of rural residents without documented land rights. They are vulnerable to the outcomes of negotiations between government, companies, and/or community leaders on the use or lease of land, often done without much input from community members.

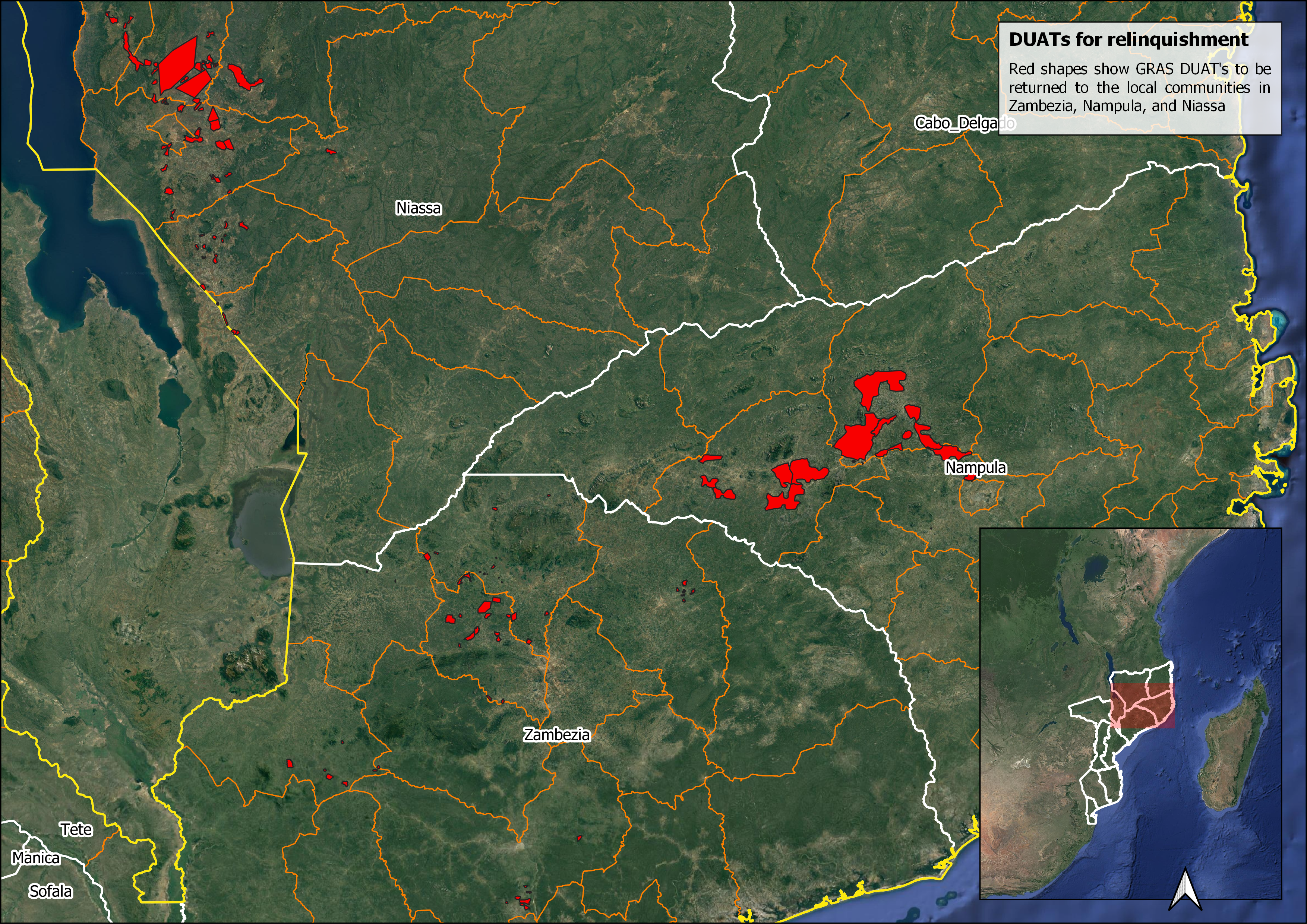

Over the course of several years, Green Resources acquired rights to 360,000 hectares scattered across Mozambique’s Niassa, Nampula, and Zambezia provinces. Since the acquisitions, Green Resources has struggled to manage these holdings. The parcels are scattered across hundreds of kilometers in the three provinces (as shown on the map below), which creates time, travel, and management costs. This is further complicated by a lack of trust between many local communities and the company. Communities point out that Green Resources, and the companies through which Green Resources acquired the land, made commitments that have not been fulfilled, such as building or improving schools and health clinics. Many of the parcels were effectively abandoned by the companies over time, leaving the communities unaware of their rights.

1 For an in-depth look at the implications of Mozambique’s colonial and modern land use policies, see Illovo private sector profile.

Map shows the landholdings Green Resources plans to disinvest from in red, which are scattered over Niassa, Nampula, and Zambezia provinces.

Map credit: Terra Firma

The Innovation

In 2019, when Green Resources came under new management, the CEO decided that the company’s scattered landholdings in Mozambique had become a liability. The company decided to disinvest, or relinquish, its rights to more than 230,000 hectares, some of which include high-value tree plantations and infrastructure.

“There was a period in Green Resources when land was seen as an asset and the accumulation of land was viewed as potential future value. Over time, the company has come to the realization that having excess land represents a liability rather than an asset: a community relations liability, reputational liability, and a commercial liability, because if you don’t have the financial means to develop the land in a reasonable time-frame, which we do not have, the land remains undeveloped, holding very little commercial value compared to the value it was once perceived to represent.”

Hans Lemm, CEO, Green Resources

Green Resources has existing unused infrastructure on many of the plots they plan to disinvest from, such as this former office that has stood abandoned since 2012. Once the company formally disinvests from the land, the Wudola community in Mocuba District, Zambezia Province hopes to transform this building into a school for adult education or a warehouse, a significant asset for a rural community with limited infrastructure.

Photo credit: Ricardo Franco

The company’s board, governed by public international investment funds Finnfund and Norfund, was eager to ensure that the return of land rights was done in a responsible, inclusive manner that guards against elite capture and prioritizes local community rights. To do this successfully, Green Resources partnered with USAID.

Land disinvestment was undertaken via two parallel tracks. First, Green Resources began the legal process of relinquishing its land and asset rights back to the government. Second, and in parallel with the company’s legal divestment process, USAID worked with communities to clarify, document, and register community boundaries.. First, Green Resources began the legal process of relinquishing its land and asset rights back to the government. Second, and in parallel with the company’s land disinvestment process, USAID worked with communities to clarify, document, and register community boundaries. Each community undertook a USAID-supported land documentation methodology, known as Mobile Applications to Secure Tenure (MAST). The MAST approach for communities includes: raising communities’ awareness of their rights and the ensuing documentation process; physically walking and delimiting communities’ boundaries; leading communities through a participatory land-use planning process that reflects current uses, needs, and a changing climate; establishing inclusive and representative community land associations; and developing and adopting community-level land-use regulations. MAST goes beyond delimiting boundaries in order to ensure a community can manage its land transparently and equitably, including outreach efforts to ensure that women, youth, and other marginalized groups are represented and actively participate throughout the MAST process, including as leaders in community land associations.

Nhumuliua community members participate in the community land documentation process in Mocuba District, Zambezia Province. Communities meet to define community limits and engage in participatory land use planning

Photo credit: Ricardo Franco

This disinvestment initiative is poised to be a win for both Green Resources and communities. The company hopes this effort will help them better manage their remaining landholdings, while repairing broken relationships with (and within) communities. The communities stand to benefit from the newly relinquished land and existing resources by asserting and formalizing their rights to these holdings, which will help reduce land conflicts and allow communities to invest in sustainable land and natural resource management practices.

The Champions

Lucia Salgado, Field Team Leader, iTC-F (implementing partner of USAID)

Lucia is a Field Team Leader for the local NGO iTC-F, a USAID implementing partner who is working with communities to carry out community land delimitations and sensitization activities on the newly relinquished Green Resources parcels. Lucia understands firsthand the importance of land documentation because the process for obtaining her own land document was challenging and time consuming. Land is a sensitive issue, and “people want evidence that we know what we are doing – my personal examples help a lot,” she says. “If I have a document that proves this land is mine, that it starts here and goes over to there, it is easier to avoid conflicts.”

Julieta Mario Massuri, Vice President, Community Land Association in Mecuburi, Nampula Province

Julieta Mario Massuri is the vice-president of the newly-established community land association Okhaliherana wo Onacuacuali (Ajuda mútua da comunidade de Nacuacuali, or Mutual Help of Nacuacuali community) in Mecuburi, Nampula Province. As a woman with disabilities, she used to feel doubly excluded in the community; after sensitization on land rights and the importance of social inclusion and gender equality in community land management, she decided to get involved. Since being elected as part of the association’s leadership, she feels that women are increasingly confident to speak up in meetings and demand accountability from the association.

Julieta says: “I feel valued and important in my community; my suggestions are heard and valid and I have space to influence positive changes for the community. We did not have a physical headquarters for the community land association, and I suggested we build one. At first people said it was too far and we could not do it, but I said if we worked together and each person carried some timber, we could get it done. We need to change our way of thinking, realize we are able to do things and not depend on external assistance.”

Hans Lemm, CEO, Green Resources

Hans Lemm has been CEO of Green Resources since 2019 and is a champion of the company’s responsible disinvestment effort. Hans believes that in order for the company to continue working in Mozambique, it must have both a legal right to operate and social legitimacy in the eyes of surrounding communities. The disinvestment initiative is an effort to repair damaged relationships with communities, while allowing the company to downsize its landholdings to a more manageable level.

Hans says: “In most places in Mozambique, our community relationships are generally solid. However, we have not always been able to deliver on our original business plans, and this has created tension between communities and the company. Successful businesses should create local jobs and make ripple effects in a positive spiral. If an area is not developed under this guise, correspondingly little development is achieved. For land-based investments, in particular, it is important that land is returned if plans cannot be implemented, so that the areas can be utilized in other ways by local people.”

The Impact

2Community delimitations included areas that were never part of GRAS parcels, as well as areas that GRAS renounced.

Green Resources is also teaching communities how to care for and replant eucalyptus trees so these resources can be a renewable source of community wealth, and the company is helping communities set up viable commercial enterprises. For example, Green Resources assisted six communities with relinquished high value parcels to sign a contract with a buyer for $120,000 worth of timber.

Community leaders report that they now feel more confident to engage with outside investors interested in their community’s resources and timber on an equal footing. One leader commented that before the community land association was formed, he would let resources in the community be taken for little to no money. Now he knows the community has rights and consults with the association on any new agreement to ensure the whole community benefits. Communities are eager to sustainably manage their land and tree plantations to generate income that can be used to achieve long-awaited benefits like community infrastructure, clinics, and schools.

Ortencia Sozinho, center, farms on an underutilized Green Resources landholding in Arejoane community, Mocuba District, Zambezia Province. Since Green Resources formally divested from the land, communities like Arejoane are able to assert their land rights, improving their tenure security. Photo credit: Ricardo Franco

A significant success of the community sensitization efforts has been increasing women’s knowledge about their rights and encouraging their participation in community land associations. Women now account for 43 percent of association members and are present in leadership roles. Lucia Salgado, who helped lead community sensitization efforts, reflected, “Some women said that they don’t know how to write so couldn’t be leaders of associations, but we helped them understand that someone who is educated can help with the writing… One aspect is to convince the woman and build her confidence, another aspect is to convince the husband that she should be able to be a leader. We are now seeing more women than before in leadership positions.” Women now report that they feel heard and have a voice in decision-making during meetings. Some women note that their community leadership roles have had follow-on impacts within their household; couples are making joint decisions about the use of household income, and some men are starting to share household tasks with their wives.

The Implications

As companies around the world audit their land-based investments and responsibilities to surrounding communities, the Green Resources case offers a compelling model for responsible, gender-responsive, inclusive land divestment. Whether divesting entire properties due to business closure or downsizing landholdings for other reasons, companies and communities alike can benefit from transparent dialogue over land management and responsible divestment that reduces opportunities for corruption.

For USAID:

USAID recognizes the scaling power of private sector partnerships and their potential role in securing land rights for communities. Yet private sector companies may not have the financial resources, technical capacity, or risk tolerance to engage in these efforts alone. USAID can act as a catalyst for responsible land based investment – or divestment – by providing financial resources, technical know-how, and capacity-building support to help the private sector effectively engage with local communities.

“The work that USAID and Green Resources are undertaking with the communities is really very unique; it holds great promise to be replicated in other parts of Mozambique and the world. Usually, community dialogue takes place when communities are trying to formalize their land rights, or when investors are negotiating with communities to gain access to land. It is not often that you find private investors who are interested in divesting and returning land to communities. Such an undertaking could have high potential for capture of land rights by local elites or by the government. To avoid this risk, USAID and Green Resources are engaging community members in a very public way, empowering community members themselves—particularly women—to lead the process, and utilizing mobile approaches to secure tenure (MAST) methodologies. This approach is already having a dramatic impact on reducing land conflicts and securing land rights and livelihoods for all members of the community.”

Mary Hobbs, Economic Growth Office Director, USAID Mozambique

For the Private Sector:

Green Resources can serve as a model for other private sector actors looking to responsibly disinvest from landholdings in a way that benefits the local communities they work with, building trust and supporting long-term development efforts in the communities while improving company profitability and reducing reputational and operational risk.

For Government:

Governments are often trying to balance community and company needs, supporting local efforts to document customary landholdings while also attracting new private sector investment to the country. The Green Resources model shows that private sector actors can partner with government to realign their investments in a way that supports community land rights while continuing to invest in and create jobs and sustainably resource management within communities.

For Communities:

This partnership demonstrates that partnering with private sector firms can act as a catalyst for – instead of an obstacle to – stronger community land rights. Communities can benefit from existing investments on the land and adopt improved land governance structures that promote good management and transparency in how they use the land, particularly in any future negotiations with outside investors. Communities also benefit from inclusive governance bodies that harness the creativity, drive, perspective, and unique abilities of diverse community members, such as women and youth.