By M. Mercedes Stickler, Land Tenure and Evaluation Specialist, USAID.

Last month, I had the opportunity to take part in the inaugural Conference on Land Policy in Africa. This event—organized by the Land Policy Initiative—highlighted the fact that land is one of the most important development issues facing Africa today.

At the conference, I presented three examples of promising approaches from USAID’s work in Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Zambia. Each of these examples demonstrates lessons learned and new approaches to land tenure challenges that we have worked with multiple stakeholders to design, pilot, evaluate, and scale up.

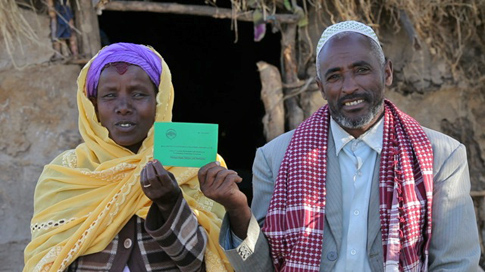

1. Land Certification in Ethiopia’s Lowland Pastoral Areas

Land Certification in the Ethiopian Highlands

Land Certification in the Ethiopian HighlandsSince 2005, USAID has supported a series of land certification schemes that have registered and surveyed over 800,000 parcels and issued over 500,000 land use certificates. Under these programs, boundaries were clarified and validated by neighbors and community members prior to certification, which reduces the likelihood of disputes among neighbors over land. The programs also piloted a method of co-registration of spouses to strengthen women’s land rights.

Preliminary evidence from the government’s own attempts to strengthen farmers’ tenure security shows a number of positive impacts: land certification was correlated with 40-45% higher land productivity in the Tigray Region and 30% higher soil and water conservation investments in the Amhara Region. The Government of Ethiopia is now scaling up this model – using new low-cost high resolution imagery –with support from the U.K. Department for International Development, the World Bank, and the Government of Finland, among others. Meanwhile, USAID is implementing an impact evaluation to measure the livelihood and production impacts of USAID-supported land certification programs in the highland regions of Ethiopia.

Following on the initial success of certification programs in the highlands, USAID recently launched a new program to strengthen community-level land rights in the pastoral areas of Ethiopia’s lowlands. This program is piloting models to map, register, and certify customary communal land use rights, as well as strengthen customary land governance arrangements. The results of this pilot will also be rigorously assessed through an independent impact evaluation, and the success of this approach could provide lessons on how to strengthen land tenure security in pastoral areas elsewhere in the region, such as in Kenya, Tanzania, and Sudan.

2. Mobile Technology Pilot to Document Land Rights in Tanzania

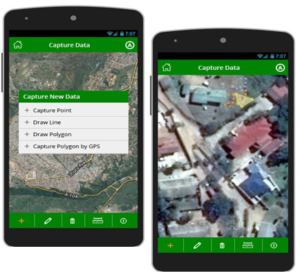

Using Mobile Technology to Map Land Rights in Tanzania

Using Mobile Technology to Map Land Rights in TanzaniaIn Tanzania, USAID is piloting an innovative approach to documenting land rights information using mobile technology. Land information, such as land claims and boundaries, is documented using low-cost and readily-available devices, such as GPS-enabled smart phones and tablets, coupled with crowd-sourced data collection methods. Under this program, USAID will train local community members to use technology to gather land rights information in rural and underserved settings. The resulting information will be used to quickly build a reliable database of land rights claims, which can then be verified by the government so that formal documentation can be issued in a more transparent, cost-effective, and timely manner, thus increasing land tenure security. USAID has built in an impact evaluation of this approach to help the Government of Tanzania and other stakeholders determine whether this is a viable alternative approach to more traditional and more costly land administration interventions.

3. Land Tenure and Climate-Smart Agriculture in Zambia

Community Land Rights Mapping in Zambia

Community Land Rights Mapping in ZambiaIn Zambia, USAID is strengthening smallholder farmers’ land and resource rights to increase investment in climate-smart agricultural practices, specifically agroforestry. Research shows that farmers who invest in agroforestry see positive benefits, including increased crop productivity and soil fertility, reduced variability in yields, and higher, more reliable farm income. However, agroforestry has not been widely adopted in the region, and while existing research suggests that tenure insecurity may be an important barrier to uptake, there has been insufficient evidence to date on how best to secure property rights to promote agroforestry adoption.

In selected sites in Zambia’s Eastern Province, USAID is piloting a series of interventions that strengthen smallholder rights to land and trees and provide agroforestry extension services to facilitate tree planting adoption and survivorship on smallholder farms. We are conducting a randomized control trial assessment to evaluate the impact of project interventions on the land use and livelihood decisions of smallholder farmers. With the consent of the customary authorities, villages were randomly assigned to receive either the agroforestry intervention, the land tenure intervention, both the agroforestry and land tenure interventions, or no intervention (the control group). A baseline survey has already been administered to 4,000 households in 315 villages, and an endline survey will be conducted in 2019. With this strong impact evaluation design, USAID hopes to quantify the correlation between secure land tenure and higher investments in agroforestry.

Supporting Missions Across 24 Countries

These are just three examples of promising approaches from our work in Africa. Across 24 countries, USAID’s Office of Land Tenure and Resource Management is supporting USAID missions to carry out projects, impact evaluations, and research activities that test and scale models to strengthen land tenure and property rights in support of key development objectives. To learn more, visit the following pages: