Originally appeared on Agrilinks.

This Q&A with Mark Freudenberger, a senior associate at Tetra Tech and director of the Land Tenure and Property Rights Sector, is part of Agrilinks’ focus on land, resource and marine tenure this April.

Agrilinks: What is land tenure and how is it different from resource tenure?

Freudenberger: Land tenure is the relationship that individuals and groups have with land, and the rules that define the ways in which property rights to land are allocated, transferred, used or managed in a particular society. Resource tenure, on the other hand, refers more broadly to the array of rights to surface and subsurface resources such as minerals. Often one finds a “bundle of rights” held by different people to access and utilize different types of resources.

Bundles of rights include, but are not restricted to, such things as the right to sell, mortgage and bequeath land; cut trees; own, lease or borrow a plot of land; dig for minerals under the land; and construct homes on leased land. This bundle can be broken up, rearranged and passed on to others. Some of these rights will be held by individuals, some by groups and others by political entities. For this reason, we often say that a mosaic of tenurial arrangements are found in a landscape ranging from ownership held by individuals, families, government or the community-at-large. See the USAID Land Tenure and Property Rights Framework for a useful glossary of terms.

Agrilinks: What’s the relationship between secure tenure and food security?

Freudenberger: Farmers need to be sure that the investments of labor and capital they make in producing food and other agricultural commodities generate a secure stream of benefits. Generally, when farmers are confident that the land is theirs, they will maintain and improve soil fertility, plant trees and invest in soil and water conservation practices. Good stewardship of the land is premised upon a belief that one has security of tenure. This does not mean that a farmer needs to have a land title or some other piece of paper in hand showing ownership. As many studies funded by USAID over the years have shown, farmers can have the perception of land tenure security even under arrangements not recognized by law.

Let’s take a case of how land ownership affects food security. When I directed the USAID Landscape Development Interventions project in southeastern Madagascar, and then later the Ecoregional Initiatives program, our agricultural extension agents encouraged farmers to fertilize their rice fields. To our dismay, we found that adoption rates were minimal. Farmers of the Tanala ethnic group living along the eastern fringes of the Fianarantsoa-Andringitra forest corridor simply would not invest in soil improvements. We thought the problem was lack of labor to collect and spread compost or difficulty obtaining credit to buy fertilizers.

We carried out a participatory assessment of the situation. To our surprise, we found that the majority of rice farmers, the long-term Tanala inhabitants of the area, had sold in distress their most valuable lowland rice plots to rich shopkeepers. In effect, the original residents had become leasers of their own land by turning over as much as three-fourths of their harvests to their landlords. Farmers were averse to investing in soil improvements because they captured so little benefit. We came to realize that unequal distribution of land was one of the central impediments to increased food production and long-term food security.

Agrilinks: Customary tenure arrangements are found throughout the world. Do these need to be formalized through land administration systems and land titling?

Freudenberger: In most of the places where USAID works, complex rules established by traditional institutions like chiefdoms or extended families with long-held historical rights to the land determine who can access, use, lease or transfer rights to both surface and sub-surface resources. We may think that these customary land tenure traditions are static and unchanging. Applied research carried out by many of the projects under the USAID Land and Urban Office has shown that tenurial regimes are constantly evolving in light of new environmental, economic and social conditions. A key issue is whether local communities perceive that they have security of tenure. When local communities believe that they control access to and use of their land, water, forests and mineral resources, it’s not necessarily the best option for public policy to promote an expensive and time-consuming national land registration process. Registration at the very local level, like at the village chief or commune level, of informal contracts and property transactions may sometimes be the best path.

For example, several years ago in Côte d’Ivoire, the USAID Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development II (PRADD II) project was mandated to support implementation of the 1998 Rural Land Law designed to convert customary tenure into a communal and private ownership. During the long process of public consultation with local communities, many questioned why government was imposing the requirement to do away with customary tenure norms and practices when indeed land owners felt secure. Indeed, clarification and recognition of customary rights by the land law opened up a Pandora’s box of conflicts and tensions. Villagers wanted nothing more but to record land leases and other agreements locally.

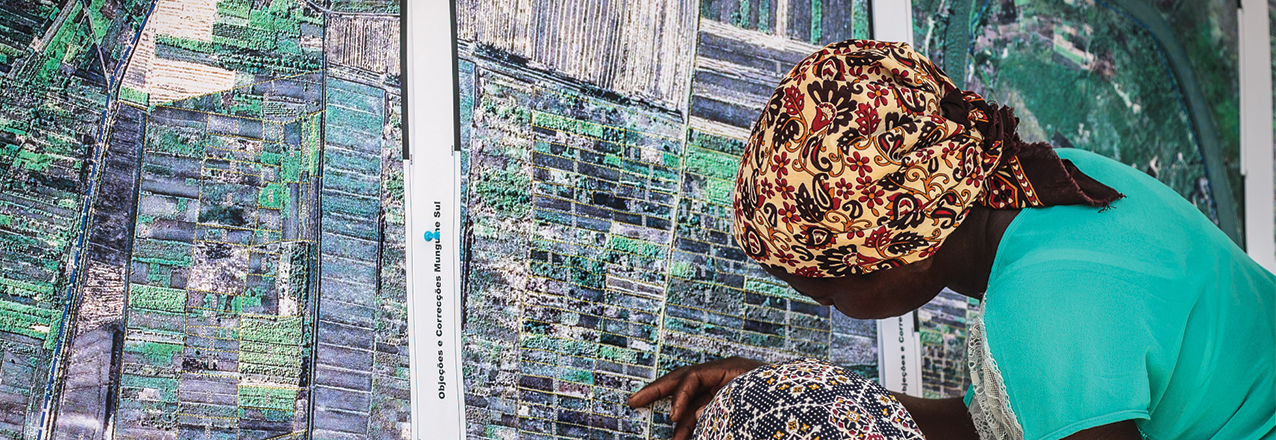

That said, from other parts of the world, we know that lands of high value — often irrigated lands or lowlands used for gardening, livestock grazing and other uses — can benefit from formal clarification, recognition and titling of the land. Conversion of customary holdings into collective or private ownership can increase security of tenure through the issuance of pieces of paper, be they formal deeds and titles, or even just slips of paper indicating ownership, sale or transfer of land. Land administration systems are needed to register these transactions. When informal land markets emerge around high value agricultural lands, especially in peri-urban areas or on irrigated plots, formalization of customary tenure is worth the investment.

From my 35 years of working in Africa, I remain impressed by the resilience of customary tenure systems. These tenurial regimes are not disappearing; rather, they are reproducing themselves, though often evolving rapidly to meet new market opportunities. For instance, in the diamond mining areas of Côte d’Ivoire, we found that communities are indeed devising new tenurial rules to help plan better the use of their territorial spaces. New tenurial arrangements have also been put in place to clarify ownership and leasing of cashew trees in response to strong international market demand. While customary tenurial systems are flexible and adaptable, I wonder whether they can withstand pressures of powerful economic interests manipulating the law to grab land for large-scale agricultural and other investment schemes. Without a formal title or deed, rural populations can be defenseless when confronted by the law.

Agrilinks: What are some examples of successes in promoting resource tenure security that contributed to greater food security?

Freudenberger: So many examples are out there of ways in which tenure security contributes to food security. For me, it’s most gratifying to see cases where programs secure rights to land for marginal peoples, especially women and the landless. For example, I am so impressed with the work of Landesa in India that supports tenure security to micro-plots, which in turn, generates significant amounts of food for households and income from sale to local markets.

From my own experience in the West African Sahel and Madagascar, and learning from examples like those of Landesa, I encouraged the PRADD II project in Côte d’Ivoire to promote micro-plots for women. In the diamond mining area of Séguéla, we worked with the local community to secure rights for women to own and manage highly degraded plots of mined out diamond pits. Women invested much labor to convert what men considered useless land into highly productive market gardens. Now, when I see flourishing small gardens in the urban fringes, or intensively managed micro-plots elsewhere, I suspect that these gardeners have somehow acquired secure access to land. How I wish I could find out for these cases how land, labor, a tiny bit of capital, and markets generate agricultural surplus.

Development practitioners sometimes fail to acknowledge that other marginalized populations contribute much to food security, for example the role livestock produced by nomadic and transhumant pastoralists plays in providing meat to Africa’s urban markets. In Ethiopia, the USAID LAND project has made great strides to secure the communal grazing lands and water rights of pastoralists in Oromia. Secure grazing rights go a long way toward assuring stable supply of livestock to regional and national meat markets and may also become the foundation of a response against violent extremism currently ripping the social fabric of rural areas.

Agrilinks: What are the success factors behind these initiatives linking tenure security with food security?

Freudenberger: For me, the key factor is that at the project design phase, development projects invested heavily in learning from the beneficiaries about local resource tenure realities. They investigated the history of land use, the root causes of resource conflicts and the conflict management practices of local communities. The project teams invested technical and financial resources to learn about the complexities of the land-labor-capital equations unfolding in each locality. Government officials, project staff and the communities themselves learned together about the social, economic and environmental factors contributing to changes in land and society. From this inclusive and participatory applied field research, development interventions were then planned with the beneficiaries to meet the tenurial challenges of the locality. Coalitions of committed actors, often those who had participated actively in the applied research, worked together at different scales to encourage public policy to incentivize recognition, clarification and registration of rights of marginalized peoples. We now know from the experience of USAID programs and projects that when people acquire the power and legitimacy to defend and advocate for their own territorial interests, be it a woman’s micro-plot or 1,000 square kilometer grazing areas of pastoralists in Ethiopia, a key ingredient of food security is put in place. However, tenure security alone is insufficient. Other complementary incentives, like strong markets, good availability of labor, or adequate provision of agricultural inputs, are also essential.

Agrilinks: What makes for a successful integration of tenure considerations into agricultural and food security programs?

Freudenberger: Participatory and inclusive applied research on land and resource tenure regimes is critical to help policymakers and project planners learn about the rapidly changing realities of urban and rural landscapes. I have worked with USAID projects in several African countries to set up consultative dialogues at the regional level to feed into national public policy forums on land tenure reforms. We often started this process by carrying out — with government officials, project planners and civil society — applied research using rapid rural appraisal techniques to learn about the complexities of local tenurial arrangements and also learn what local populations recommend as policy adjustments. We took government policymakers, land administrators and judges to live in villages for a couple of weeks at a time to listen to the people, and from this, devise appropriate public policies around land. These learning experiences enabled national elites to appreciate local realities, and often from these life-changing encounters, become supporters of policies and programs to improve land tenure security for rural populations.