Tell us about yourself.

I am a Geospatial Analyst and have been applying geospatial data and technology to a wide range of issues in the international development field for over 12 years. Currently, with the Land and Urban Office within USAID’s Bureau for Economic Growth, Education, and Environment (E3), I focus on integrating geospatial data, analysis, and technology to support evidence-based decision-making across land governance and urban programming. I also lead the Land and Urban Office’s gender equality and women’s empowerment work related to land governance and property rights.

Why is land important to USAID?

Land is a critical economic asset, allowing people to live a more secure and productive life. Secure land and property rights lead to economic growth and provide incentives for investment and sustainable resource management. Less secure tenure, on the other hand, can lead to conflicts, instability, and the exclusion of vulnerable populations, especially women. USAID’s mission is to end extreme poverty, promote resilient societies, and end the need for foreign assistance; therefore, addressing the issue of weak land tenure and property rights is essential for achieving Agency’s development objectives.

How can spatial data help USAID understand and strengthen land tenure and property rights?

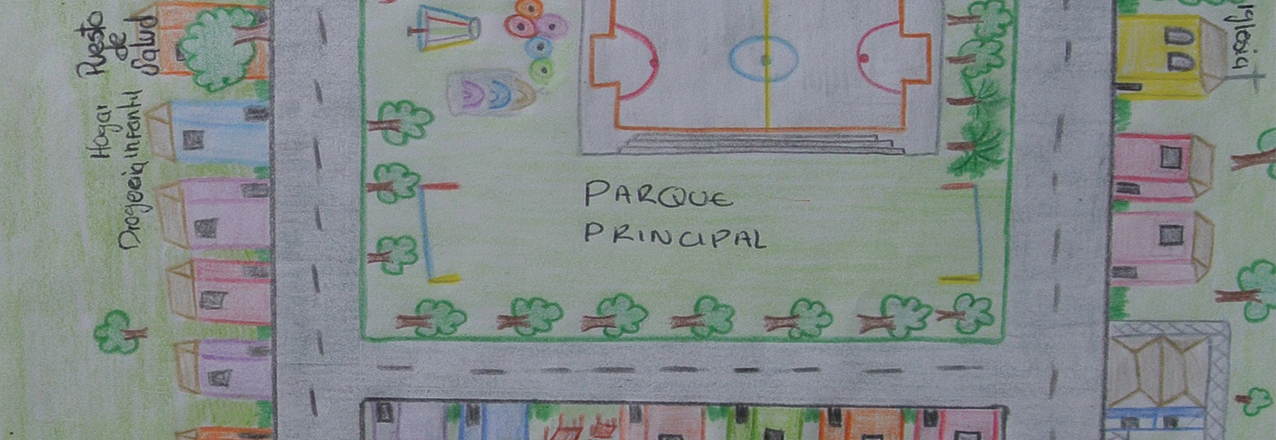

USAID uses spatial data to demarcate parcels and to map and clarify different land and resource uses for collectively managed land. This can help resolve land conflicts between neighbors as well as clarify overlapping interests. Simply knowing the boundary of one’s own parcel increases landholders’ perception of secure property rights, especially if the process of mapping the parcel’s boundary leads to some form of documented land rights – a certificate of occupancy or land use rights, for example.

The power of geospatial data is that relevant information can be collected and linked to geographic features. For example, along with actual boundaries, we can collect additional information on the type of ownership or occupancy, gender, use rights, crop type, and yield productivity and fertilizer use. This information, linked to the boundary data, can be displayed and analyzed in a spatial way to help local people, communities, traditional leaders, and governments understand and better manage their resources.

At USAID, we have developed and successfully piloted a flexible and participatory Mobile Applications to Secure Tenure (MAST) approach, which links an easy-to-use mobile phone application and a data management platform to help communities map, record, and document their land and resources. Geospatial data is a key component of this approach.

We recently launched a new program, Land Technology Solutions (LTS), focusing on the application of technology and geospatial data to address challenges in the land and resource governance sector.

Leveraging the power of geospatial data and analysis also allows USAID to evaluate impacts of land tenure interventions, identify gaps, and inform decisions regarding future investments in the land sector. For example, our office is using data collected through a series of rigorous impact evaluations to incorporate spatial data and visualization as a tool for making high evidence-based investment programming.

What is the role of USAID’s E3/Land and Urban Office?

The main role of USAID’s Land and Urban Office is providing high quality technical assistance to USAID missions to address land and resource rights in an effort to build resilient societies. We also invest in innovative technology solutions and partnerships to mobilize local resources and identify practices that provide long-term sustainability on our investment to reduce donor dependency across developing world. Given the cross-cutting nature of land tenure and property rights, the Land and Urban Office is consistently building the Agency’s technical awareness and capacity by creating and sharing knowledge and evidence.

What are some of your biggest accomplishments in the land sector?

Working together with local communities to find and implement solutions that improve their lives is what attracted me to the international field 12 years ago.

USAID’s Land and Urban Office has emphasized using participatory approaches to map, document and manage land resources, which has proven to be cost-effective, efficient, and flexible across different contexts. For example, I manage the coastal spatial planning and mangrove management activity under the Tenure and Global Climate Change (TGCC) program, which has piloted an innovative, highly participatory approach to develop a sustainable coastal and mangrove management approach in three communities in Vietnam. The process was driven by the communes, who jointly collected spatial data and conducted surveys, discussed overlapping resource uses, and decided on a plan for future management of coastal resources. The spatial data and maps help them better understand the current conditions of their resource and to make informed decision on their future management.

It is exciting to see the dedication to this activity from the local government and the interest by the provincial and central governments generated by the pilot. But the most exciting and satisfying aspect for me is to see the enthusiasm of the communes’ members, who took the idea of using tablets to map and understand conditions of their coastal resources and ran with it, with the hope of a better and brighter future.

Final thoughts?

My final thoughts are focused on women’s land rights. Many people think that land tenure is a complicated issue and it can be addressed only through large and expensive land registration efforts. USAID’s land tenure work has demonstrated evidence that working at small scales with local communities and addressing different elements of complex land tenure and property rights issues has greater impact on local communities’ livelihoods. For example, providing women with secure rights to land by building awareness about women’s legal rights to inheritance and property, or simply adding a line on land certificate forms to include the name of the wife (not just the husband) during the land documentation process can have a powerful impact on women’s lives, food security, and economic opportunities. Women with secure land tenure and property rights are more likely to invest in agricultural inputs, apply sustainable agriculture practices, and undertake economic opportunities, leading to improved food security and economic benefits to the entire household. Strengthening women’s land rights is central to USAID’s Land and Urban office objectives and contributes to USAID’s women’s empowerment programming strategy.