Originally published on the International Institute for Environment and Development blog.

Across much of Africa, land is not allocated and inherited under statutory law but through customary practices rooted in kinship. In patrilineal systems, land belongs to men’s families and is inherited through the paternal line.

In Zambia, many ethnic groups follow a matrilineal system, where women own land and pass it down the maternal line.

But ownership does not necessarily translate into access, use and control of land. Even in matrilineal societies, social and gender norms undermine women’s decision-making power. Traditionally – regardless of patrilineal or matrilineal systems − men have authority over household resources, including land − so when it comes to land rights, women are left out.

In Zambia’s customary systems chiefs and their advisors – known as indunas – and village headpersons allocate land. These customary leaders are usually men and, as custodians of tradition and culture, heavily influence whether harmful gender norms and practices persist or change.

Recognizing their influence, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded ‘Integrated Land and Resource Governance (ILRG)‘ program piloted an approach to engage these traditional leaders in shifting harmful gender norms and strengthening women’s land rights in Zambia’s Eastern province, to support a parallel systematic land documentation process. Ninety-six indunas and village headpersons (32% women) from seven chiefdoms participated in a year-long three-part dialogue series.

The dialogues provided indunas with a safe space to reflect and take positive action. The first session analyzed gender inequalities in ownership, access and control of land. The second session envisioned the change indunas wanted and their role to bring about that change. In the final session, indunas discussed achievements and challenges over the year.

Dialogue Leads to Action

Through the dialogues, the indunas made promising steps to shift gender norms that hinder women’s land rights. In five chiefdoms, indunas facilitated local discussions about harmful traditions, such as sending divorcees and widows away from the villages.

These discussion forums triggered an upsurge in the number of women bringing their cases to the chief’s attention. In four chiefdoms, indunas drafted by-laws supporting women’s land rights and banning property grabbing.

Some indunas who now support changing land records to reflect land given to women reached out to traditional courts to raise awareness about the shift. In the patrilineal Nzamane chiefdom, a woman – for the first time in history – was appointed as village headperson with full authority and decision-making power.

A woman headperson in the Nyamphande chiefdom addressed a pressing form of gender-based violence related to land: the use of traditional funeral rites to deny widows’ access to their deceased spouse’s land.

Indunas and village headpersons who participated in the dialogues encouraged men in their communities to include their wives in land documentation. And the indunas led by example, committing to share their own land with their wives and children, both boys and girls.

Induna Jacob Phiri, from Mnukwa chiefdom, was the first to share his land after the first dialogue session, saying “My wife had access to my land and planted crops of her own choice, but I never thought about what could happen to her if I died. I knew I needed to act while I was still alive, so I gave her a portion of land to be her own. After that, I felt empowered to tell people in my village to do the same.”

Not All Indunas Embrace Change

Despite promising shifts in behaviors and gender norms, many indunas did not support change − taking a backseat or even attempting to block and discourage those willing to drive it forward.

Although bringing together indunas from different chiefdoms intended to foster collaboration, the pilot initiative found that individual action by the indunas was much more successful than collective action.

Some of the indunas resisted changes in social norms, and it is important to invest more time in supporting the indunas and headpersons to have a deeper understanding of existing gender norms that should be changed before moving to planning and implementation.

Change Starts with Community

The pilot showed that shifting harmful gender norms at the community level is crucial in supporting women to access land rights. Given their role in regulating local culture and advising the traditional authority on land administration, customary leaders like indunas and village headpersons are a key entry point for that shift.

Change can be slow. But spaces for dialogue, critical reflection, and support for action-planning enabled the indunas to not only change their own beliefs, but also begin to see their role and their communities in a different light.

Between house visits, Mayor Mancera, who used a mask throughout the entire video to limit the spread of COVID-19, stopped and looked at the camera explaining to her followers how Fuentedeoro’s Municipal Land Office is playing a key role in allowing her to formalize public properties like schools and health clinics, as well as lands that were donated by the city for social housing.

Between house visits, Mayor Mancera, who used a mask throughout the entire video to limit the spread of COVID-19, stopped and looked at the camera explaining to her followers how Fuentedeoro’s Municipal Land Office is playing a key role in allowing her to formalize public properties like schools and health clinics, as well as lands that were donated by the city for social housing. She repeatedly reminded her audience and the new landowners that without their commitment and confidence in local government, Fuentedeoro’s Municipal Land Office would not be able to process their titles. It is true that without community buy-in, building a formal land market is practically impossible.

She repeatedly reminded her audience and the new landowners that without their commitment and confidence in local government, Fuentedeoro’s Municipal Land Office would not be able to process their titles. It is true that without community buy-in, building a formal land market is practically impossible.

Since 2015, USAID has worked in rural Iringa District, the heart of Tanzania’s southern agricultural region, to strengthen land rights and systematically address the lack of land documentation. Over the past five years, USAID/Tanzania’s Land Tenure Activity (LTA) helped villages and the district land office demarcate more than 70,000 land parcels and register more than 60,000 land certificates (known as CCROs), all using USAID’s digital

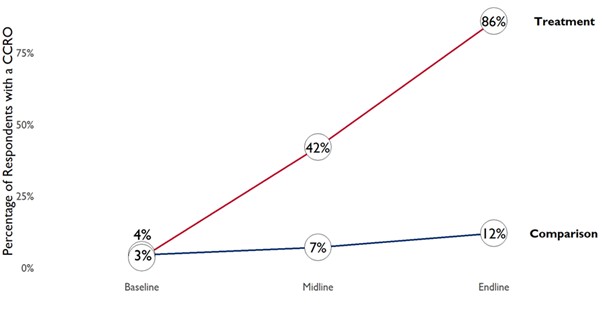

Since 2015, USAID has worked in rural Iringa District, the heart of Tanzania’s southern agricultural region, to strengthen land rights and systematically address the lack of land documentation. Over the past five years, USAID/Tanzania’s Land Tenure Activity (LTA) helped villages and the district land office demarcate more than 70,000 land parcels and register more than 60,000 land certificates (known as CCROs), all using USAID’s digital  The impact evaluation of LTA has helped USAID measure the activity’s effect on land-related outcomes and understand how systematic certification of customary land rights affects smallholder farmers’ tenure security, investment decisions, empowerment, and broader livelihoods. With increasing land pressures and widespread concerns about land grabbing, knowing the impacts of formalized customary use rights is relevant to both farmers and policymakers.

The impact evaluation of LTA has helped USAID measure the activity’s effect on land-related outcomes and understand how systematic certification of customary land rights affects smallholder farmers’ tenure security, investment decisions, empowerment, and broader livelihoods. With increasing land pressures and widespread concerns about land grabbing, knowing the impacts of formalized customary use rights is relevant to both farmers and policymakers.

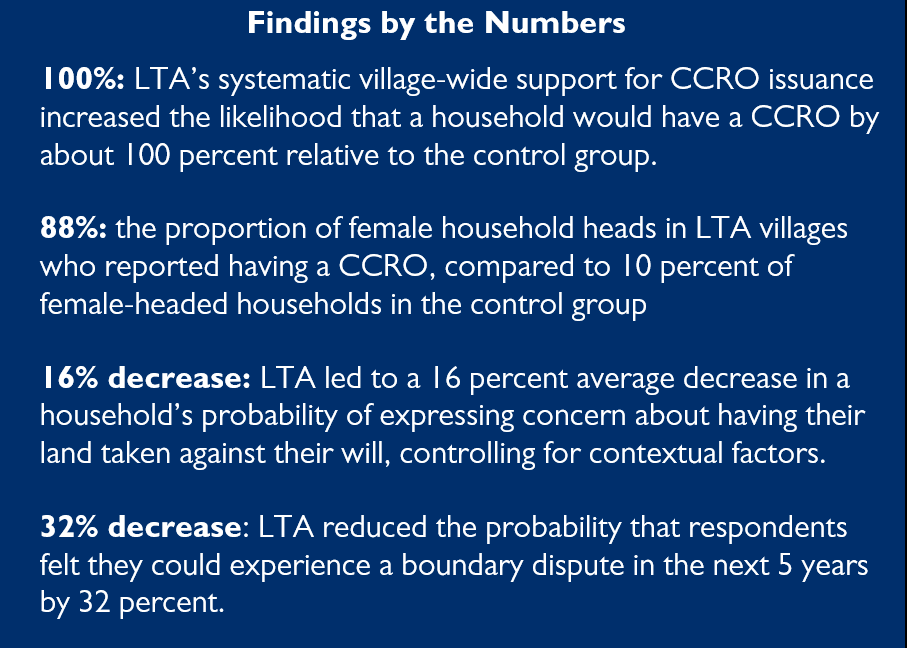

Tenure security improved for both men and women, and to a greater extent for female relative to male households heads. The evaluation also found a substantial increase in tenure security for female primary spouses supported by LTA. These improvements are especially important in the rural Tanzanian context, where women often have a harder time claiming and defending their land rights or exercising control over land decisions. Based on the evaluation results, USAID/Tanzania’s support for formalized customary land documentation seems to have not only expanded people’s access to CCROs but also led to more equitable access to land documentation in ways that allay gender-based concerns around land grabbing.

Tenure security improved for both men and women, and to a greater extent for female relative to male households heads. The evaluation also found a substantial increase in tenure security for female primary spouses supported by LTA. These improvements are especially important in the rural Tanzanian context, where women often have a harder time claiming and defending their land rights or exercising control over land decisions. Based on the evaluation results, USAID/Tanzania’s support for formalized customary land documentation seems to have not only expanded people’s access to CCROs but also led to more equitable access to land documentation in ways that allay gender-based concerns around land grabbing.