USAID is echoing the voices of women asserting their rights to land.

As part of the 16 days of activism to end violence against women and girls, LFP talked to Judith Rodríguez, a member of AFROMUVARAS, an association of afro-Colombian women who farm cacao in the Rescate Las Varas Community Council in Tumaco, Nariño.

As part of the 16 days of activism to end violence against women and girls, LFP talked to Judith Rodríguez, a member of AFROMUVARAS, an association of afro-Colombian women who farm cacao in the Rescate Las Varas Community Council in Tumaco, Nariño.

Despite violence against women in her municipality and community, people are changing their mentality. Women, in particular, are becoming aware of their rights to land and the importance of their contributions to the productive development of their collective territories and the care of their families.

In 2021, USAID’s Land for Prosperity Activity created a public-private partnership in the cacao value chain in Tumaco, which seeks to strengthen farmer associations like AFROMUVARAS so they can improve the quality of their cacao and access new markets. The cacao association was founded in 2017 and has 367 members.

What has the experience of having a collective land title for AFROMUVARAS been like?

JR: For us women, the collective land title means we are taking back what once was ours. As women, we are always forced to depend on men. Lately, there has been a lot of progress, and we are very thankful for it. In AFROMUVARAS it has been a wonderful experience to be part of this big group of women who want to develop their territory and improve the quality of life for women in rural areas. We want to make progress collectively, to be the voice of women in these regions, to take a chance on peace, on the wellbeing of our children, on the growth of our territory, as well as to generate employment opportunities and grow as a business.

In the Community Council, you share the land between members. Do you think the women who own land individually or jointly with their partners are as protected as you?

In the Community Council, you share the land between members. Do you think the women who own land individually or jointly with their partners are as protected as you?

JR: Yes, I think working with men or living with their partners and their children, if they have a title they are protected. I mean, we are betting every day on personal and territorial growth, this is the foundation. Working hand in hand, every day, with our families.

AFROMUVARAS knows of cases of economic violence against women in Tumaco?

JR: You can’t see it, but you can feel the economic violence, because women always depend on men or their partners. They expect the man to be the one that provides, and when he gets home he decides what everyone can do. It is harder for women to generate our own income and provide because usually, they do not have the same education or economic opportunities. And the men take advantage of this to exert economic violence, because there are fewer employment opportunities for women in Tumaco. Men always get the opportunity to work first.

There are laws to stop men from selling common properties without the consent of their partners. Do you think there is a need to talk about these laws more widely?

There are laws to stop men from selling common properties without the consent of their partners. Do you think there is a need to talk about these laws more widely?

JR: Yes, we need more outreach, so that women know these laws. So they can feel empowered enough around these issues to be sure that they are important. Land and property are their rights.

In AFROMUVARAS, do you think the way rural men and women think is changing? Is violence against women diminishing? How?

JR: Yes, things are changing. And I am very proud to answer this and it makes me smile, to see how women are taking part in many collective processes, participating in spaces where we are invited. We are raising our voices and protesting. These processes are empowering women, but there is still a lot of work to do. It is a long and difficult process. For example, today the President of our Community Council is a woman.

Why should the women of Tumaco have hope?

JR: We can be hopeful, very hopeful. If we work together, if we continue to be united as women, hand in hand, and continue to empower ourselves in social and educational issues, we can continue to grow in our territory.

How do you encourage other women to understand and recognize their rights?

JR: Today, from the rural areas of Tumaco, from our Community Council and our organization, as a member of AFROMUVARAS and also as a person, I tell women in neighboring areas that we are all women, we should all be empowered, we should work together, be strong and keep fighting. We can’t give up, we need to persist, be sisters and look for spaces where we can grow and be equal to men. We need to be present in those spaces to get what we want, because we can do it. We can participate in public spaces, social spaces, everywhere we want as women, we can grow and take a chance on peace.

One early morning in 1994, Gloria Ester Buelvas was woken and told she had to leave her grandfather’s farm in San Pedro de Urabá, where she had lived 16 years of her life. Nearly three decades later, Buelvas still does not know why she and dozens of members of her family were threatened and forced to leave their hometown.

One early morning in 1994, Gloria Ester Buelvas was woken and told she had to leave her grandfather’s farm in San Pedro de Urabá, where she had lived 16 years of her life. Nearly three decades later, Buelvas still does not know why she and dozens of members of her family were threatened and forced to leave their hometown. Colombia’s Urabá region stretches from the border of Panama along the Caribbean coast and is famous for bananas and large cattle ranching estates. Over generations, the region became a textbook example of the type of class divisions between landless farmers and an elite land-owning class that fomented strife and erupted in brazen warfare between the leftist guerrillas and paramilitary groups in the nineties. Families like the Buelvas were caught in the middle, accused of helping or supporting one side or the other.

Colombia’s Urabá region stretches from the border of Panama along the Caribbean coast and is famous for bananas and large cattle ranching estates. Over generations, the region became a textbook example of the type of class divisions between landless farmers and an elite land-owning class that fomented strife and erupted in brazen warfare between the leftist guerrillas and paramilitary groups in the nineties. Families like the Buelvas were caught in the middle, accused of helping or supporting one side or the other. Over the years, the municipality provided relief, including improved roads and electricity, and the families rebuilt their lives. Gloria and her neighbors supported each other through subsistence agriculture, but none have ever obtained a land title for their property.

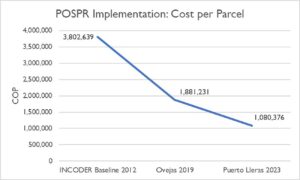

Over the years, the municipality provided relief, including improved roads and electricity, and the families rebuilt their lives. Gloria and her neighbors supported each other through subsistence agriculture, but none have ever obtained a land title for their property.  When the cadaster of Puerto Lleras was last updated in 2011, it included 2,300 properties. Following the implementation of the 2023 POSPR, the initiative surveyed over 4,600 properties, many of which are home to displaced families. More than half of these parcels are not recognized by the state but are ready to be formalized and issued a registered land title.

When the cadaster of Puerto Lleras was last updated in 2011, it included 2,300 properties. Following the implementation of the 2023 POSPR, the initiative surveyed over 4,600 properties, many of which are home to displaced families. More than half of these parcels are not recognized by the state but are ready to be formalized and issued a registered land title. Puerto Lleras is one of

Puerto Lleras is one of

USAID is promoting an innovative land administration strategy that supports the creation of Regional Land Offices (RLOs) in partnership with regional governments across Colombia. RLOs address issues of land formalization in municipalities with limited resources. RLO land formalization teams, which include a land surveyor and legal expert, rotates around the department, working in municipalities where local leaders have limited budgets and experience with titling property. The strategy takes advantage of economies of scale, allowing municipal leaders to share costs, and strengthens land use planning between municipal and regional leaders. RLOs interface with Colombia’s property registry authority, the Superintendence of Notaries and Registers, which is often located far from rural municipalities. They also assist with the titling of properties in urban areas, including public properties with schools and health centers, and provide technical assistance and training.

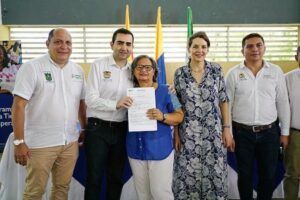

USAID is promoting an innovative land administration strategy that supports the creation of Regional Land Offices (RLOs) in partnership with regional governments across Colombia. RLOs address issues of land formalization in municipalities with limited resources. RLO land formalization teams, which include a land surveyor and legal expert, rotates around the department, working in municipalities where local leaders have limited budgets and experience with titling property. The strategy takes advantage of economies of scale, allowing municipal leaders to share costs, and strengthens land use planning between municipal and regional leaders. RLOs interface with Colombia’s property registry authority, the Superintendence of Notaries and Registers, which is often located far from rural municipalities. They also assist with the titling of properties in urban areas, including public properties with schools and health centers, and provide technical assistance and training. At the event, regional leaders delivered 146 land titles to landowners in the municipalities of Arjona, Calamar, Cartagena, El Carmen de Bolívar, Magangué, Mahates, María la Baja, San Jacinto, San Juan Nepomuceno, Santa Rosa del Sur, and Simití. RLOs ensure gender equality and a total of 108 land titles benefited women. The Bolívar RLO plays a central role in the Departmental Land Working Group, which coordinates tasks related to land administration and property formalization in the department in efforts to increase the efficiency of land titling and promote a culture of formal land ownership.

At the event, regional leaders delivered 146 land titles to landowners in the municipalities of Arjona, Calamar, Cartagena, El Carmen de Bolívar, Magangué, Mahates, María la Baja, San Jacinto, San Juan Nepomuceno, Santa Rosa del Sur, and Simití. RLOs ensure gender equality and a total of 108 land titles benefited women. The Bolívar RLO plays a central role in the Departmental Land Working Group, which coordinates tasks related to land administration and property formalization in the department in efforts to increase the efficiency of land titling and promote a culture of formal land ownership. W.R: A well-organized office brings people closer to the habits of legal land ownership so that their land titles can be passed from generation to generation and from owner to owner. It is an invitation to the community to align itself with the office, to resolve their doubts with clear and accurate information, and to learn how to do land transactions moving forward.

W.R: A well-organized office brings people closer to the habits of legal land ownership so that their land titles can be passed from generation to generation and from owner to owner. It is an invitation to the community to align itself with the office, to resolve their doubts with clear and accurate information, and to learn how to do land transactions moving forward. J.V: Without a doubt it can and will be over time. The Bolivar Regional Land Office is a strategic ally to reach each of the municipalities and the villages in corregimientos, and veredas in Bolívar. I believe the office is the critical link to continue formalizing land and properties, and to convert registered property titles into a positive habit of the community.

J.V: Without a doubt it can and will be over time. The Bolivar Regional Land Office is a strategic ally to reach each of the municipalities and the villages in corregimientos, and veredas in Bolívar. I believe the office is the critical link to continue formalizing land and properties, and to convert registered property titles into a positive habit of the community.

Fuentedeoro is known for plantains. The municipality is located in Colombia’s eastern plains, a vast region of large rivers that drain the Andes into the Amazon basin. In this landscape, Luz Dary Mendoza learned farming from her father, who grew a variety of crops in the fertile plains. But his livelihood and family’s future always depended on the revenue generated from the region’s cash crop: the plantain.

Fuentedeoro is known for plantains. The municipality is located in Colombia’s eastern plains, a vast region of large rivers that drain the Andes into the Amazon basin. In this landscape, Luz Dary Mendoza learned farming from her father, who grew a variety of crops in the fertile plains. But his livelihood and family’s future always depended on the revenue generated from the region’s cash crop: the plantain. The Rural Property and Land Use Plan, known by its Spanish acronym POSPR, seeks to change this paradigm. The initiative, which surveys and updates the cadaster for every parcel in the municipality, was recently carried out by Colombia’s National Land Agency with USAID support. Land formalization teams surveyed almost 4,500 rural parcels, covering Fuentedeoro’s more than 56,000 hectares. The land administration plan discovered that some 2,000 plots are ready to be formalized. Among these plots are the farms of Luz Dary Mendoza and 19 AGROSARDI members.

The Rural Property and Land Use Plan, known by its Spanish acronym POSPR, seeks to change this paradigm. The initiative, which surveys and updates the cadaster for every parcel in the municipality, was recently carried out by Colombia’s National Land Agency with USAID support. Land formalization teams surveyed almost 4,500 rural parcels, covering Fuentedeoro’s more than 56,000 hectares. The land administration plan discovered that some 2,000 plots are ready to be formalized. Among these plots are the farms of Luz Dary Mendoza and 19 AGROSARDI members. Under Luz Dary’s leadership, AGROSARDI joined a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) focused on plantain agribusiness. The PPP, which was facilitated by USAID Land for Prosperity, is valued at more than USD $250,000 and links critical investments from the public and private sectors to nearly 200 plantain farmers in and around Fuentedeoro.

Under Luz Dary’s leadership, AGROSARDI joined a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) focused on plantain agribusiness. The PPP, which was facilitated by USAID Land for Prosperity, is valued at more than USD $250,000 and links critical investments from the public and private sectors to nearly 200 plantain farmers in and around Fuentedeoro. Thanks to the plantain PPP, farmers are learning Good Agricultural Practices (GAP). AGROSARDI will generate cleaner, agrochemical-free crops. GAP also promotes soil recovery through the use of organic fertilizers, resulting in cleaner plantain suitable for human consumption.

Thanks to the plantain PPP, farmers are learning Good Agricultural Practices (GAP). AGROSARDI will generate cleaner, agrochemical-free crops. GAP also promotes soil recovery through the use of organic fertilizers, resulting in cleaner plantain suitable for human consumption.

The invasion occurred in 2010, and Jairo Gómez was there. He was one of a multitude of victims and families displaced by the violence that had engulfed their region and pushed them out of their homes. Gómez pounded in wooden posts, hung a tarp and hammock, and braced himself for the inevitable backlash. In less than a week, the police showed up with teargas and violence to evict the families. Gómez stood his ground.

The invasion occurred in 2010, and Jairo Gómez was there. He was one of a multitude of victims and families displaced by the violence that had engulfed their region and pushed them out of their homes. Gómez pounded in wooden posts, hung a tarp and hammock, and braced himself for the inevitable backlash. In less than a week, the police showed up with teargas and violence to evict the families. Gómez stood his ground. Social leaders emerged, and soon they were laying lines to create the lots for dwellings and future roads. By the end of the first year, 5,000 people lived in 9 de Agosto, which anywhere else was known as the barrio de los desplazados, or displaced people.

Social leaders emerged, and soon they were laying lines to create the lots for dwellings and future roads. By the end of the first year, 5,000 people lived in 9 de Agosto, which anywhere else was known as the barrio de los desplazados, or displaced people. This year, with USAID support Tierralta made a giant step towards incorporating the neighborhood into the town’s masterplan by titling more than 260 parcels. The event featured Mayor Daniel Montero delivering property titles to a packed auditorium, and was significant on several levels. First, as a clear example of the government providing families with a tangible asset that will inevitably lead to improvements in their neighborhood; second, the event represents the single largest delivery of land titles made by a municipal administration in the history of Colombia. “The wait times for government services are slow and you can never get everything done, but today we have fought for something beautiful,” Montero said to the crowd. “A land title will bring you new opportunities and hopefully bring peace, happiness, and hope to your homes.”

This year, with USAID support Tierralta made a giant step towards incorporating the neighborhood into the town’s masterplan by titling more than 260 parcels. The event featured Mayor Daniel Montero delivering property titles to a packed auditorium, and was significant on several levels. First, as a clear example of the government providing families with a tangible asset that will inevitably lead to improvements in their neighborhood; second, the event represents the single largest delivery of land titles made by a municipal administration in the history of Colombia. “The wait times for government services are slow and you can never get everything done, but today we have fought for something beautiful,” Montero said to the crowd. “A land title will bring you new opportunities and hopefully bring peace, happiness, and hope to your homes.” The Colombian government has struggled to facilitate land planning in areas affected by the conflict or to provide residents with services to legalize the properties of informal settlements like 9 de Agosto.

The Colombian government has struggled to facilitate land planning in areas affected by the conflict or to provide residents with services to legalize the properties of informal settlements like 9 de Agosto. With USAID’s support, Tierralta’s Municipal Land Office has improved its capacity to title urban property and reduced processing times from multiple years to just a few months. Key to the process is the improvement in communication and work flow between land agencies, or in this case with Colombia’s property registry authority, the Superintendence of Notaries and Registers (SNR). By working directly with the regional SNR office, Tierralta’s Land Office can title dozens of properties at a time.

With USAID’s support, Tierralta’s Municipal Land Office has improved its capacity to title urban property and reduced processing times from multiple years to just a few months. Key to the process is the improvement in communication and work flow between land agencies, or in this case with Colombia’s property registry authority, the Superintendence of Notaries and Registers (SNR). By working directly with the regional SNR office, Tierralta’s Land Office can title dozens of properties at a time. Since 2020, 42 USAID-supported Municipal and Regional Land Offices delivered over 6,800 land titles to families living in the urban areas of rural municipalities. In addition, the land offices have formalized more than 1,600 public properties and provided land and property services to more than 16,000 citizens.

Since 2020, 42 USAID-supported Municipal and Regional Land Offices delivered over 6,800 land titles to families living in the urban areas of rural municipalities. In addition, the land offices have formalized more than 1,600 public properties and provided land and property services to more than 16,000 citizens.

Theirs is one of 30 land titles delivered at an event earlier this year by Chaparral’s Municipal Land Office (MLO), which was created with support from the Land for Prosperity. The Land Office operates under the Municipality’s Secretary of Planning and is something of a one-stop shop for local land administration. It facilitates rural development initiatives and allows the local leaders to deliver on state-led land titling strategies that take the onus off land owners.

Theirs is one of 30 land titles delivered at an event earlier this year by Chaparral’s Municipal Land Office (MLO), which was created with support from the Land for Prosperity. The Land Office operates under the Municipality’s Secretary of Planning and is something of a one-stop shop for local land administration. It facilitates rural development initiatives and allows the local leaders to deliver on state-led land titling strategies that take the onus off land owners. For now, the Municipal Land Office is operating thanks to Natalia Quinoñes. As the MLO’s legal expert, she reviews hundreds of urban properties and provides citizens with information to begin to understand the complexity of Colombia’s land laws and the process of property formalization. Quiñones graduated in law last year and is relatively new to the land administration. In her job, learning is a continuous process, and she studies how land laws are evolving in today’s Colombia.

For now, the Municipal Land Office is operating thanks to Natalia Quinoñes. As the MLO’s legal expert, she reviews hundreds of urban properties and provides citizens with information to begin to understand the complexity of Colombia’s land laws and the process of property formalization. Quiñones graduated in law last year and is relatively new to the land administration. In her job, learning is a continuous process, and she studies how land laws are evolving in today’s Colombia. LFP helped to delineate the city’s urban perimeter, verified the geodesic network, and divided the municipality into workable intervention units. The parcel visit phase has begun and rural families in Chaparral are participating in the process. The POSPR is surveying an area of more than 88,000 hectares and approximately 8,600 parcels. More than 2,600 parcels are expected to be titled by the National Land Agency.

LFP helped to delineate the city’s urban perimeter, verified the geodesic network, and divided the municipality into workable intervention units. The parcel visit phase has begun and rural families in Chaparral are participating in the process. The POSPR is surveying an area of more than 88,000 hectares and approximately 8,600 parcels. More than 2,600 parcels are expected to be titled by the National Land Agency.

Through our analysis, we understand that deforestation in Chiribiquete is closely linked to land access and property issues and land grabbing. We see five big deforestation hotspots inside Chiribiquete that correspond to two areas in San Vicente del Caguán, two sections going towards San José del Guaviare, and one area which is the northern border of the Yaguará II indigenous reservation. Then we have zones such as San Miguel that, although they are not very large, already show evidence of deforestation.

Through our analysis, we understand that deforestation in Chiribiquete is closely linked to land access and property issues and land grabbing. We see five big deforestation hotspots inside Chiribiquete that correspond to two areas in San Vicente del Caguán, two sections going towards San José del Guaviare, and one area which is the northern border of the Yaguará II indigenous reservation. Then we have zones such as San Miguel that, although they are not very large, already show evidence of deforestation. I think that in the case of the areas around the national park, in theory it can contribute. We have the designations, such as the parks and forest reserves, but I think forest reserves have lost their validity, despite being a mechanism to ensure that the forests can be preserved and exploited in a sustainable way. With Colombia’s issues in terms of land access for rural communities, deforestation is a result not only of people colonizing the forests, but in many cases, it’s a result of government policies. In the case of the Amazon Forest Reserve, the government directed and promoted new colonies and occupation, and they did it with counterproductive policies that people still have ingrained in their heads in terms of what is required for someone to consider themselves the owner of a piece of land. So today, people who do not have grass or cows, do not feel they are owners. So, regulations and land use planning exist, but in the end, what transforms the land are the people who do not have the right tools or knowledge and receive no support from the government.

I think that in the case of the areas around the national park, in theory it can contribute. We have the designations, such as the parks and forest reserves, but I think forest reserves have lost their validity, despite being a mechanism to ensure that the forests can be preserved and exploited in a sustainable way. With Colombia’s issues in terms of land access for rural communities, deforestation is a result not only of people colonizing the forests, but in many cases, it’s a result of government policies. In the case of the Amazon Forest Reserve, the government directed and promoted new colonies and occupation, and they did it with counterproductive policies that people still have ingrained in their heads in terms of what is required for someone to consider themselves the owner of a piece of land. So today, people who do not have grass or cows, do not feel they are owners. So, regulations and land use planning exist, but in the end, what transforms the land are the people who do not have the right tools or knowledge and receive no support from the government. I think they are on multiple fronts, for example, in terms of prevention, patrolling, and control, and the application of environmental law. USAID has a number of actions and programs that are strengthening government entities, and they are carrying out projects and providing tools to the communities that allow them to make better use of their land. USAID has initiatives around communication and awareness raising that I think are vital, and that helps to bring that knowledge and that work closer to the communities.

I think they are on multiple fronts, for example, in terms of prevention, patrolling, and control, and the application of environmental law. USAID has a number of actions and programs that are strengthening government entities, and they are carrying out projects and providing tools to the communities that allow them to make better use of their land. USAID has initiatives around communication and awareness raising that I think are vital, and that helps to bring that knowledge and that work closer to the communities. If we don’t coordinate efforts and work with the communities in the northern part, Chiribiquete does not have a high rate of survival in the medium term. The process of deforestation moves fast, and every day there is more transformation. If we don’t make the indigenous communities who are protecting the southern parts of the park our natural partners, it is very likely that a time will come when there will also be deforestation in that region. So, our first challenge is to work with the communities, to make them our natural partners for conservation. Without discriminating between indigenous and farmer communities but including everyone.

If we don’t coordinate efforts and work with the communities in the northern part, Chiribiquete does not have a high rate of survival in the medium term. The process of deforestation moves fast, and every day there is more transformation. If we don’t make the indigenous communities who are protecting the southern parts of the park our natural partners, it is very likely that a time will come when there will also be deforestation in that region. So, our first challenge is to work with the communities, to make them our natural partners for conservation. Without discriminating between indigenous and farmer communities but including everyone.

Leany Alba, 28, grew up in Bogota and dreamed of being a professional photographer, but her parents never warmed up to the idea. She always loves maps and followed a career path towards becoming a cartographer. On that path, she found a burgeoning job market for her current profession: land surveyor.

Leany Alba, 28, grew up in Bogota and dreamed of being a professional photographer, but her parents never warmed up to the idea. She always loves maps and followed a career path towards becoming a cartographer. On that path, she found a burgeoning job market for her current profession: land surveyor.

“With today’s technology, there is no excuse. Any woman can work as a land surveyor.” says Leanny.

“With today’s technology, there is no excuse. Any woman can work as a land surveyor.” says Leanny. “So one of the challenges is communication with people. Women often have better communications skills, and it is necessary to have a certain tact in dealing with rural people, since almost nobody understands land” explains Leany Alba.

“So one of the challenges is communication with people. Women often have better communications skills, and it is necessary to have a certain tact in dealing with rural people, since almost nobody understands land” explains Leany Alba.