A Municipal Land Office in Valencia, Córdoba is helping families protect their property for future generations

Ana Espitia lost her mother two years ago. One day after the funeral, her brother insisted on selling the home that was still in her mother’s name. She was worried and unaware of how she could fight her brother to keep the house where she grew up and had taken care of her cancer-stricken mother in her final years.

“I was always by my mother’s side and I was going to fight for her home,” Espitia explains. “Then I heard that there was a land office in our municipality, and there, a lawyer explained the process to me.

In 1986, when Espitia was just 12, her mother bought the property in Valencia, a small town in northern Colombia, as a way to escape the violence that was increasing across rural areas. If she were forced to sell the home, she would have to find a place to rent in Valencia in an unfavorable real estate market.

Javier Guerra, the Municipal Land Office’s coordinator, explained to Espitia that in order to sell the property, her brother would need to gather all the signatures of her siblings. She was relieved and began studying how she could legally transfer the title into her name.

“Thanks to the Municipal Land Office, I got the type of advice that a lawyer would charge us a lot of money for, because property issues are always complicated here,” she says.

Espitia worked with her siblings to clarify the ownership of the land. In November 2021, the local land office put the cherry on top when it delivered the registered property title in Ana Espitia’s name. Valencia’s municipal government delivered a total of 45 land titles to residents like Ana Espitia, families who have waited over 30 years to finally prove they are bona fide owners of their properties. Espitia, who works as a cook in an elementary school, got time off from her job to attend the ceremony at the municipal park.

Ana Espitia has made improvements on her childhood home, located in Valencia, Córdoba in Northern Colombia.

Ana Espitia has made improvements on her childhood home, located in Valencia, Córdoba in Northern Colombia.

The Municipal Land Office was first created in 2015 with USAID support and titled dozens of urban properties in the town’s center. The office, which is embedded in the Municipal Urban Planning Office, ramped up operations last year with additional USAID support. In 2021, the office delivered a total of 68 land titles in 2021.

“The Land Office is a big achievement and a great success for municipal administrators and the community. We are bringing land titling to families who have waited 60 years to be recognized as land owners. As a team we are now bringing these services to Valencia’s rural communities, explaining to them that land titling is a process that is totally free.”

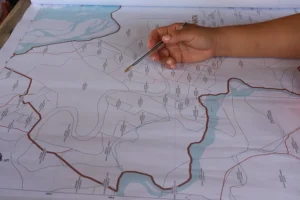

The local land office also plays an important role as liaison for the National Land Agency (ANT), which is leading a massive land formalization campaign in Valencia. The office’s local knowledge is critical for the government’s land formalization teams to understand and manage social dynamics, reach communities, and improve efficiency in identifying and understanding land ownership. The methodology, which was jointly designed by USAID and the ANT, collects property data across the entire municipality, mediates land conflicts, and reduces redundancy among land-related entities. The methodology, which combines land titling with updating the municipal cadaster, helps the government to reduce costs by up to 60% as well as the time it takes to formalize a property and streamline that with the nation’s cadaster.

“It’s important to recognize these efforts of the municipality, since they are not physically visible, but they are of great benefit to the population and communities and together we are fighting to create a municipality of property owners,” Martínez says.

Over the last two years, the USAID-funded Land for Prosperity program (LFP) has supported the creation or re-launch of 26 Municipal Land Offices across Colombia. These offices have already titled more than 1,100 properties for families and over 400 public properties like health clinics and schools. USAID is strengthening the capacity of local leaders to maintain formal land ownership, manage land transactions, and enhance the culture of formalization. Using an approach that develops the capacity of public servants and reaches rural communities has the potential to improve the relationship between the public and government institutions while establishing conditions for leaders to mobilize critical funds for improving their municipalities.

USAID-supported municipal land offices have identified over 39,700 parcels and almost 1,000 public parcels that can be titled through their respective municipalities.

USAID-supported municipal land offices have identified over 39,700 parcels and almost 1,000 public parcels that can be titled through their respective municipalities.

Willing to Invest

With her land title, Ana Espitia has a new outlook on life and gets excited about making investments in her home and yard. She is already planning to pour a concrete floor and improve the bedrooms with doors.

“It’s much easier to make an investment when you know the title is in your hands,” she says. “I feel like I can better organize my life and live with less anxiety.”

In addition, the future of her children also takes on a new meaning. With the land title in her name, she knows she can pass the land down to her daughter and their families.

“Knowing my children can benefit from the land makes life more comfortable.” – Ana Espitia

Hamilton’s Life

Hamilton Rodríguez came to Valencia, Córdoba in the year 2000, after his father was killed in El Carmen de Bolívar, Bolívar, where they used to live. After the wave of violence, Hamilton settled in Valencia and in 2013 bought the parcel where he now lives with his wife and four of their eight children. The parcel includes the backyard where Hamilton and his wife grow corn and ñame, and the front porch where Hamilton has his mechanics shop and fixes motorcycles.

However, when Hamilton bought his parcel he did it through an unregistered contract, and he did not receive a formal title to his property. In 2019 Colombia’s Rural Agricultural Planning Unit estimated that 70% of Valencia’s citizens did not have a formal title to their property.

To settle one’s debts

In late 2019, Hamilton submitted the paperwork to formalize his parcel but he ran into a problem. “They told me I had to settle all the cadaster debts from my parcel and I had to pay over COP $1 million (around USD $300).” It was very difficult for Hamilton to pay this amount, especially since one of his sons, aged 22, needed surgery to remove a recently discovered tumor. The family had to cover a lot of medical expenses related to the hospital and medicine, and did not have the money to pay the cadaster debt.

Luckily, thanks to Valencia’s Municipal Land Office, the municipality cancelled all debts and allowed him to start the payments from scratch. Thanks to this decision, Hamilton continued with the titling process and was one of the 45 owners who received their property titles in November 2021. Now that they are the formal owners of their parcel, Hamilton and his wife plan to improve and expand their home and his shop.

Valencia, Cordoba, Colombia

© 2022 Land for Prosperity

Cross posted from Land for Prosperity Exposure site

A massive property sweep

A massive property sweep Helping to bring the massive titling endeavor is a team of more than 100 land formalization experts that coordinates with community leaders and triangulates information to the ANT and other agencies. The team is composed of land surveyors, legal experts, and social workers who are well into year two of operation.

Helping to bring the massive titling endeavor is a team of more than 100 land formalization experts that coordinates with community leaders and triangulates information to the ANT and other agencies. The team is composed of land surveyors, legal experts, and social workers who are well into year two of operation.

Cáceres has long been of strategic importance to USAID and the government, and this attention has led to a cluster of initiatives. Joint efforts in the territory go beyond the municipality-wide land formalization campaign. USAID’s comprehensive rural development strategy is also developing the capacity of rural producers, such as honey producers in Bajo Cauca, and engaging the private sector to invest in conflict-affected municipalities. By focusing on general issues in rural development, USAID land tenure programming addresses property-related challenges while opening financing routes to reach underfunded areas. This approach bridges the gap between a land title and rural development and helps the government achieve its goals to build self-reliance and promote a more stable, peaceful, and prosperous Colombia.

Cáceres has long been of strategic importance to USAID and the government, and this attention has led to a cluster of initiatives. Joint efforts in the territory go beyond the municipality-wide land formalization campaign. USAID’s comprehensive rural development strategy is also developing the capacity of rural producers, such as honey producers in Bajo Cauca, and engaging the private sector to invest in conflict-affected municipalities. By focusing on general issues in rural development, USAID land tenure programming addresses property-related challenges while opening financing routes to reach underfunded areas. This approach bridges the gap between a land title and rural development and helps the government achieve its goals to build self-reliance and promote a more stable, peaceful, and prosperous Colombia. Nuevo Jerusalem paints an accurate picture of how towns are created in today’s Colombia: through invasiones or informal settlements created by internally displaced people (IDP). Colombia is home to a population of more than 6 million IDP—second only to Syria—and has the unfortunate distinction of being the world’s country with the highest number of IDPs and the least number of refugee camps.

Nuevo Jerusalem paints an accurate picture of how towns are created in today’s Colombia: through invasiones or informal settlements created by internally displaced people (IDP). Colombia is home to a population of more than 6 million IDP—second only to Syria—and has the unfortunate distinction of being the world’s country with the highest number of IDPs and the least number of refugee camps.

How can Municipal Land Offices support Puerto Libertador?

How can Municipal Land Offices support Puerto Libertador?

USAID provided the mayor and his council with expertise and consulting to get the ordinance across the finish line. As part of the negotiation, the council agreed that newly formalized landowners would be exempt from taxes in 2022 and will only begin paying property taxes in 2023.

USAID provided the mayor and his council with expertise and consulting to get the ordinance across the finish line. As part of the negotiation, the council agreed that newly formalized landowners would be exempt from taxes in 2022 and will only begin paying property taxes in 2023. The Story of Tax Collection

The Story of Tax Collection

Foundational Diagnostics

Foundational Diagnostics The Municipal Land Office’s first task is carrying out a diagnostic of Puerto Libertador’s existing properties. The analysis has revealed that at least 3,600 parcels are able to be formalized by the office, including 240 public parcels that should be formalized in the name of the municipality, such as schools, health clinics, municipal parks, and city buildings.

The Municipal Land Office’s first task is carrying out a diagnostic of Puerto Libertador’s existing properties. The analysis has revealed that at least 3,600 parcels are able to be formalized by the office, including 240 public parcels that should be formalized in the name of the municipality, such as schools, health clinics, municipal parks, and city buildings.

“By supporting the Municipal Land Office and land formalization, USAID is also supporting rural development, a in this particular case, improving the local health clinic,” said Héctor Sepúlveda, LFP’s Regional Coordinator of Bajo Cauca Antioqueño, where Valencia is located.

“By supporting the Municipal Land Office and land formalization, USAID is also supporting rural development, a in this particular case, improving the local health clinic,” said Héctor Sepúlveda, LFP’s Regional Coordinator of Bajo Cauca Antioqueño, where Valencia is located.

“Fuentedeoro is the kind of place where people won’t open the door to strangers or give out personal information. People do not feel safe, and with the recent presidential elections, there is still a lot of uncertainty in the air.

“Fuentedeoro is the kind of place where people won’t open the door to strangers or give out personal information. People do not feel safe, and with the recent presidential elections, there is still a lot of uncertainty in the air.

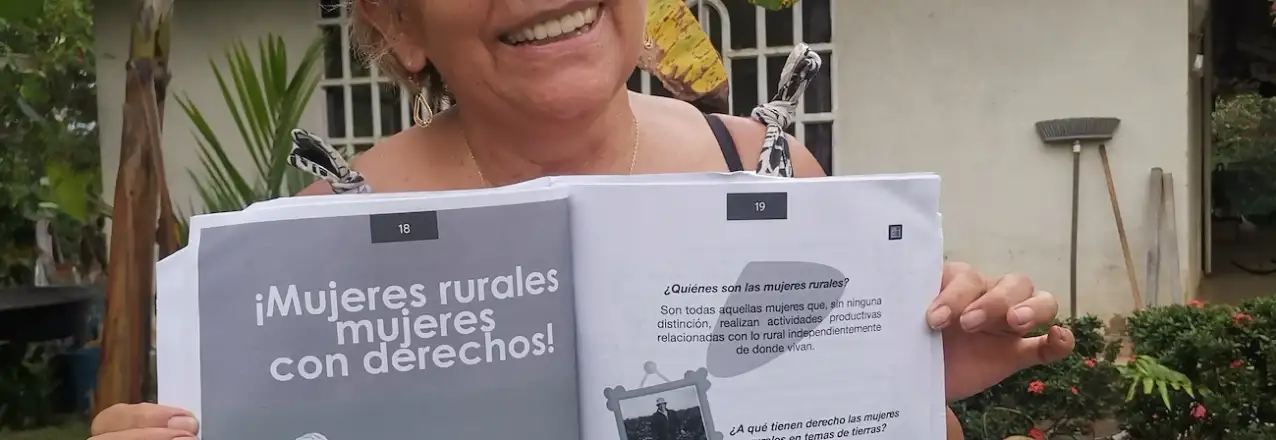

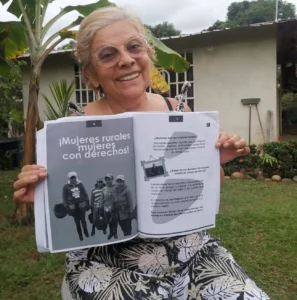

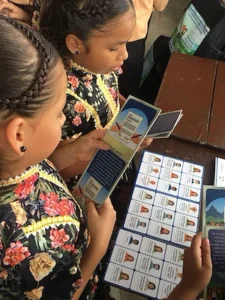

Large land formalization campaigns rely heavily on social workers and outreach, and community liaisons like Luz Estela Velandia are one of the most effective ways to ensure participation. Trusted and motivated neighbors can fill the spaces where the government has been absent. Many in Fuentedeoro have long distrusted the government and believe land titling is just a ploy to take their land away. To overcome this information barrier, Velandia mobilizes her neighbors through neighborhood Whatsapp groups, where she can quickly reach 150 families living in her village.

Large land formalization campaigns rely heavily on social workers and outreach, and community liaisons like Luz Estela Velandia are one of the most effective ways to ensure participation. Trusted and motivated neighbors can fill the spaces where the government has been absent. Many in Fuentedeoro have long distrusted the government and believe land titling is just a ploy to take their land away. To overcome this information barrier, Velandia mobilizes her neighbors through neighborhood Whatsapp groups, where she can quickly reach 150 families living in her village.

“Legalizing property is fundamental. If not, we find ourselves in this bottleneck that, if they are not legalized, no investment can be made in them. Historically, no one cared about legalizing property, and the land administration process was poorly executed. This is an example of a mistake from the past that brings us consequences today.”-Diana Navarro, Mayor of Puerto Rico

“Legalizing property is fundamental. If not, we find ourselves in this bottleneck that, if they are not legalized, no investment can be made in them. Historically, no one cared about legalizing property, and the land administration process was poorly executed. This is an example of a mistake from the past that brings us consequences today.”-Diana Navarro, Mayor of Puerto Rico In the Municipality’s Name

In the Municipality’s Name