USAID and the Colombian Government are clearing up land and property conflicts in Cáceres in order to promote a formal land market and spur rural development

In 2011, Walter Tapia was lucky enough to find a small house near his father in the town of Buenos Aires, located in Cáceres, an isolated municipality in northern Colombia. He put money and sweat into the cinder block house by adding a cement floor, tiling the bathroom, and improving the kitchen’s countertops and backsplash. By 2017, his house felt like a home.

That same year, the owner of the land showed up knocking on his door to ask Walter why he was living in a home built on the owner’s land. Walter never knew the land had a previous owner and the only proof of ownership he had was a notarized compra-venta, denoting how much he paid for the house. Such receipts are typical for property transactions in rural Colombia. Now, Walter faces a difficult negotiation process and a legal battle that he’s not prepared to stage or pay for.

More than a decade before, the mayor of Cáceres had granted a group of empty lots to poor, rural families, but the government provided them with neither a registered land title nor any type of housing subsidies to assist with housing. Unable to build their homes, most of the families moved away in search of other opportunities. Later on, a subsequent mayor provided other families with housing subsidies, and they then unknowingly built on the already spoken for lots.

Two doors down lives Walter’s sister. She found out she faces the same issue as Walter, earlier this year. Around the corner there are more, hundreds of cases more. This neighborhood of Buenos Aires is a textbook example of the type of confusion surrounding property ownership in rural municipalities like Cáceres.

“I don’t want to spend any more money on fixing up my house, because I have no idea what is going to happen and I might never see it again,” a dejected Walter says.

A massive property sweep

A massive property sweep

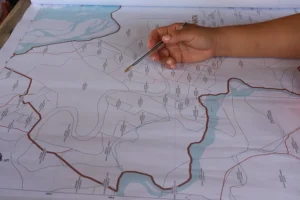

In Cáceres, Colombia’s land administration agencies hope to clear up these types of land conflicts using a land formalization methodology developed by USAID and promoted by the government. The multipurpose cadaster campaign updates the municipality’s official plot map—known as the cadaster—delivers land titles to landowners and brings much needed clarity to property ownership. The campaign, overseen by the National Land Agency (ANT) and supported by USAID, is based on a similar land titling pilot successfully carried out in the municipality of Ovejas, Sucre between 2018 and 2019.

The innovative approach is based on a strategy that integrates social outreach, careful legal analysis, and critical coordination with government agencies to update land ownership information for Cáceres’ more than 11,000 parcels. The methodology has evolved since the Ovejas Pilot, improving through lessons learned, and is proving that a massive approach, which combines titling and cadaster, reduces redundancy. When land entities work together, the government can reduce costs by 60% as well as the time it takes to formalize a property and update the rural cadaster.

Helping to bring the massive titling endeavor is a team of more than 100 land formalization experts that coordinates with community leaders and triangulates information to the ANT and other agencies. The team is composed of land surveyors, legal experts, and social workers who are well into year two of operation.

Helping to bring the massive titling endeavor is a team of more than 100 land formalization experts that coordinates with community leaders and triangulates information to the ANT and other agencies. The team is composed of land surveyors, legal experts, and social workers who are well into year two of operation.

In Cáceres, 8 out of 10 properties are informally owned. Properties are typically passed down from generation to generation, abandoned by families due to violence, or been granted by local government, but without land titles. But due to violence stemming from territorial disputes, the last time Colombia’s cadaster authority, IGAC, updated the municipality’s map of properties was in 2003.

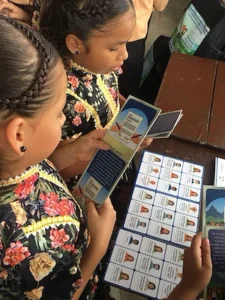

To confront the lack of the public’s experience and knowledge related to a formal land market, the campaign employs a robust social strategy that relies on a group of 20 community leaders. The community leaders are essential in order to reach residents with important information about the process and key dates to keep on the calendar.

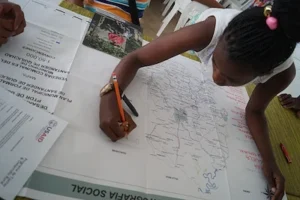

Ana Cristina Marchena is a community leader who lives down the road from Walter Tapia. She is working with the land formalization campaign to prepare residents with the information they need. Marchena and her colleagues received training in basic land tenure policy and how to title a property in Colombia. She prepares residents for exercises in social mapping, assists with locating residents who have been displaced, and helps communities flag major land conflicts in their neighborhoods or towns.

“The campaign’s workers cannot simply go into a rural community. They need somebody who knows the people, and my community recognizes me as a leader because I am always working with women and children. The community trusts me, and I can speak to them in their language,” says Marchena.

Perhaps Marchena’s most important role is as the nexus between the land formalization teams and armed groups who continue to play a role in the lives of so many rural villagers. As a trusted leader, Marchena can communicate with armed actors and prepare villages for the land formalization activities without unexpected episodes of violence resulting in turf wars or misunderstandings.

A far-reaching campaign

USAID is supporting 11 municipal-wide land titling campaigns across Colombia. Each campaign depends on a variety of factors and is expected to require an average of two years to complete implementation. By 2025, the government will have updated more than 115,000 parcels in the national cadaster with the possibility of delivering up to 40,000 land titles.

The updated rural land cadaster will include high-resolution maps defining property borders with more precision than ever before in the region’s history. A detailed cadaster reduces land conflicts and gives the local and regional governments critical information to plan land use strategies and investments that meet the needs of the population.

Team of land formalization experts in Colombia.

Beyond land tenure: integrated development

Cáceres has long been of strategic importance to USAID and the government, and this attention has led to a cluster of initiatives. Joint efforts in the territory go beyond the municipality-wide land formalization campaign. USAID’s comprehensive rural development strategy is also developing the capacity of rural producers, such as honey producers in Bajo Cauca, and engaging the private sector to invest in conflict-affected municipalities. By focusing on general issues in rural development, USAID land tenure programming addresses property-related challenges while opening financing routes to reach underfunded areas. This approach bridges the gap between a land title and rural development and helps the government achieve its goals to build self-reliance and promote a more stable, peaceful, and prosperous Colombia.

Cáceres has long been of strategic importance to USAID and the government, and this attention has led to a cluster of initiatives. Joint efforts in the territory go beyond the municipality-wide land formalization campaign. USAID’s comprehensive rural development strategy is also developing the capacity of rural producers, such as honey producers in Bajo Cauca, and engaging the private sector to invest in conflict-affected municipalities. By focusing on general issues in rural development, USAID land tenure programming addresses property-related challenges while opening financing routes to reach underfunded areas. This approach bridges the gap between a land title and rural development and helps the government achieve its goals to build self-reliance and promote a more stable, peaceful, and prosperous Colombia.

The new Jerusalem

For 800 families, Nuevo Jerusalem is still a dream. The new settlement, located 30 kilometers from Cáceres, Antioquia sees one or two new families arrive every day. Most of them have been displaced from their homes due to the violence and threats that make life impossible in this pocket of rural Colombia known as Bajo Cauca. With nowhere to go, the families attempt to integrate into shanty towns with scrap wood and plastic coverings. Every month, hundreds of people begin their journey to create a home for their families.

Nuevo Jerusalem paints an accurate picture of how towns are created in today’s Colombia: through invasiones or informal settlements created by internally displaced people (IDP). Colombia is home to a population of more than 6 million IDP—second only to Syria—and has the unfortunate distinction of being the world’s country with the highest number of IDPs and the least number of refugee camps.

Nuevo Jerusalem paints an accurate picture of how towns are created in today’s Colombia: through invasiones or informal settlements created by internally displaced people (IDP). Colombia is home to a population of more than 6 million IDP—second only to Syria—and has the unfortunate distinction of being the world’s country with the highest number of IDPs and the least number of refugee camps.

With no water, sewage, or electricity, Nuevo Jerusalem will eventually require the municipality of Cáceres to face a problematic reality: find the resources to invest in infrastructure for these displaced families and rezone the land to allow for residential use.

“This is how cities expand in today’s Colombia. The problem is that the municipal government is underfunded and cannot meet the needs of these families,” explains Wilmer Molina, a social worker employed by the Cáceres Municipal Land Office. “On the other hand, the town’s population could mean more than 800 votes, so maybe somebody will help them someday.”

“Unfortunately that’s how Colombia works.”

Through his work, Molina is entwined with Cáceres land issues. He represents one part of a multi-pronged effort supported by USAID to clear up confusion around land ownership, update the municipality’s property cadaster, deliver land titles to residents, and promote a functioning land market. The Municipal Land Office (MLO) is an integral part of Colombia’s National Land Agency’s goal to ensure that the municipality’s 11,000 plus parcels are formalized and reflected in the nation’s rural cadaster. The MLO is located in downtown Cáceres and receives dozens of people each week looking for answers about their properties, laws, and procedures.

© 2022 Land for Prosperity

Cross posted from Land for Prosperity Exposure site

How can Municipal Land Offices support Puerto Libertador?

How can Municipal Land Offices support Puerto Libertador?

USAID provided the mayor and his council with expertise and consulting to get the ordinance across the finish line. As part of the negotiation, the council agreed that newly formalized landowners would be exempt from taxes in 2022 and will only begin paying property taxes in 2023.

USAID provided the mayor and his council with expertise and consulting to get the ordinance across the finish line. As part of the negotiation, the council agreed that newly formalized landowners would be exempt from taxes in 2022 and will only begin paying property taxes in 2023. The Story of Tax Collection

The Story of Tax Collection

Foundational Diagnostics

Foundational Diagnostics The Municipal Land Office’s first task is carrying out a diagnostic of Puerto Libertador’s existing properties. The analysis has revealed that at least 3,600 parcels are able to be formalized by the office, including 240 public parcels that should be formalized in the name of the municipality, such as schools, health clinics, municipal parks, and city buildings.

The Municipal Land Office’s first task is carrying out a diagnostic of Puerto Libertador’s existing properties. The analysis has revealed that at least 3,600 parcels are able to be formalized by the office, including 240 public parcels that should be formalized in the name of the municipality, such as schools, health clinics, municipal parks, and city buildings.

“By supporting the Municipal Land Office and land formalization, USAID is also supporting rural development, a in this particular case, improving the local health clinic,” said Héctor Sepúlveda, LFP’s Regional Coordinator of Bajo Cauca Antioqueño, where Valencia is located.

“By supporting the Municipal Land Office and land formalization, USAID is also supporting rural development, a in this particular case, improving the local health clinic,” said Héctor Sepúlveda, LFP’s Regional Coordinator of Bajo Cauca Antioqueño, where Valencia is located.

“Fuentedeoro is the kind of place where people won’t open the door to strangers or give out personal information. People do not feel safe, and with the recent presidential elections, there is still a lot of uncertainty in the air.

“Fuentedeoro is the kind of place where people won’t open the door to strangers or give out personal information. People do not feel safe, and with the recent presidential elections, there is still a lot of uncertainty in the air.

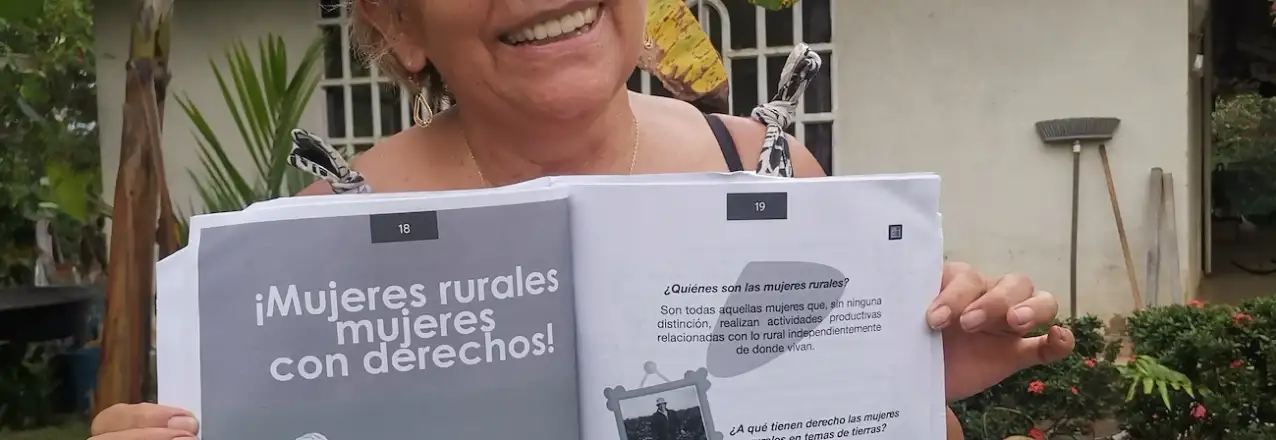

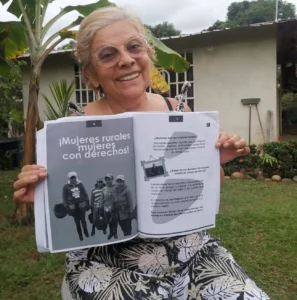

Large land formalization campaigns rely heavily on social workers and outreach, and community liaisons like Luz Estela Velandia are one of the most effective ways to ensure participation. Trusted and motivated neighbors can fill the spaces where the government has been absent. Many in Fuentedeoro have long distrusted the government and believe land titling is just a ploy to take their land away. To overcome this information barrier, Velandia mobilizes her neighbors through neighborhood Whatsapp groups, where she can quickly reach 150 families living in her village.

Large land formalization campaigns rely heavily on social workers and outreach, and community liaisons like Luz Estela Velandia are one of the most effective ways to ensure participation. Trusted and motivated neighbors can fill the spaces where the government has been absent. Many in Fuentedeoro have long distrusted the government and believe land titling is just a ploy to take their land away. To overcome this information barrier, Velandia mobilizes her neighbors through neighborhood Whatsapp groups, where she can quickly reach 150 families living in her village.

“Legalizing property is fundamental. If not, we find ourselves in this bottleneck that, if they are not legalized, no investment can be made in them. Historically, no one cared about legalizing property, and the land administration process was poorly executed. This is an example of a mistake from the past that brings us consequences today.”-Diana Navarro, Mayor of Puerto Rico

“Legalizing property is fundamental. If not, we find ourselves in this bottleneck that, if they are not legalized, no investment can be made in them. Historically, no one cared about legalizing property, and the land administration process was poorly executed. This is an example of a mistake from the past that brings us consequences today.”-Diana Navarro, Mayor of Puerto Rico In the Municipality’s Name

In the Municipality’s Name