Cross-posted from AgriLinks

Since 2019, PepsiCo and USAID have been working together to empower female farmers in West Bengal where they have PepsiCo local staff and agronomists providing trainings to women in the potato supply chain, equipping them to take on the role of community agronomists, and supporting women’s self-help groups access land leases to grow PepsiCo potatoes. As a result, women in the PepsiCo potato supply chain are producing higher quality and quantity of potatoes, expressing feelings of increased empowerment and finding support from their families and communities. Given their success in West Bengal, USAID and PepsiCo have expanded their work in India and to three more countries — Pakistan, Vietnam and Colombia — through a new Global Development Alliance funded through USAID’s women’s economic empowerment funding.

Sarah Lowery, economist and public-private finance specialist in USAID’s Land and Resource Governance Division, and Corinne Hart, senior gender advisor for energy, environment and climate at USAID’s Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Hub, share how PepsiCo is helping USAID make the business case for women’s empowerment.

Why did USAID partner with PepsiCo?

Sarah: The partnership began as a conversation between PepsiCo and USAID about the impediments of insecure land rights to achieving PepsiCo’s sustainability goals, and it developed into a collaboration to strengthen land rights and empower women in PepsiCo’s supply chains. We began working through our existing Integrated Land and Resource Governance (ILRG) activity in West Bengal to understand the myriad roles women already play in potato production, provide them with support, training and access to land, and shift harmful gender norms that limit their opportunities.

Corinne: Following the successes with ILRG, USAID hosted a cocreation workshop with PepsiCo, where we discussed strategies to make the case that women’s empowerment and gender equality in their agriculture supply chains can be a core part of their business; critical to advancing their sustainable agriculture goals and key performance indicators (KPIs). This partnership also has the overall goal of making the business case for women’s empowerment in the food and beverage industry as a whole. The International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) is a key partner providing a robust, evidence-based, gender-sensitive approach to the activity. We’re looking at shifting power dynamics, harmful gender norms, supporting women in gaining access to productive assets like land and also increasing their personal empowerment. Our strategic approach includes involving men to increase their understanding and enthusiasm about the benefits that accrue to the family when women in their households have a more recognized relationship with PepsiCo.

What are some of the results for women that you’ve seen?

Corinne: The data shows that women who are participating in this activity report that they feel seen and respected as farmers for the first time. We are tracking data on women participants’ perceptions of their own self-worth and how others in the community see them. These qualitative metrics are critical to understanding women’s empowerment, alongside quantitative indicators such as income earned and access to training and skills building. Measuring changes in perceptions of self-worth and personal empowerment are incredibly important components of women’s economic empowerment.

Sarah: Women are seeing their husbands become more supportive of them and their role as farmers. For example, we are working to create new roles for women as community agronomists. Initially, maybe their husbands or families did not believe they could or should do the job, but they have transformed these perceptions either by the influence of gender equality champions in the community, or seeing their wives be successful in these roles. We hear stories where women say “my husband didn’t think I could do it, and now he is taking my agronomic advice.” Women have persevered and continued to advocate for themselves and have become sources of information both for women in the community and for men as well. We’ve seen some of the biggest skeptics of our work become the most adamant champions.

Have there been any surprising results of this partnership?

Sarah: During this partnership, PepsiCo announced its 2030 Goal to Scale Regenerative Farming Practices Across 7 Million Acres, by “improving the livelihoods of more than 250,000 people in its agricultural supply chain and communities, including economically empowering women.” Our USAID-PepsiCo partnership has played a pivotal role in demonstrating that empowering women is possible and is good for business. And to measure progress against its livelihoods and other goals, PepsiCo is developing its Livelihoods Measurement Framework. Critically, the framework includes measurement of gender equality. This is really important because if you’re not being asked to measure your progress on something, you may not think about it.

Corinne: PepsiCo is building its capacity at all levels to understand and see their business activities through a gender lens. This activity and its initial successes are attracting interest from other companies, as well as other local PepsiCo teams. Other industry actors are now reaching out to see how we can partner and share our approaches. PepsiCo has already been showcasing what they are doing and working to get other companies in the sustainable agriculture industry to think about how women’s empowerment and gender equality is linked to their ability to achieve their sustainable agriculture goals.

Sarah: Another unexpected impact we have found is that some communities are associating the gender equality interventions — like assisting women’s groups access land to lease, providing agronomic trainings for women, installing a local community agronomist in the area, providing gender norms workshops, etc. — with PepsiCo in such a positive way that they have said, “We want to be a PepsiCo village.” Due to this initial success, PepsiCo is now seeing women’s empowerment as a part of a broader farmer loyalty strategy.

What are some of the lessons learned in working with the private sector?

Corinne: One of the big lessons has been that stakeholders across the company are motivated by different things and come with varying levels of interest. The local PepsiCo teams sometimes have additional, locally-specific priorities and pressures than the PepsiCo global sustainable agriculture team, and local company leaders have a huge amount of pressure and demand on resources and meeting their business targets. We have learned to tailor our messaging to different stakeholders across the company so that we can demonstrate the value-add of these activities to them, as well as making sure we are really clear about what would be expected of them.

Sarah: Particularly for the local business leaders who are focused on achieving their business targets, addressing gender inequality seems like an extra responsibility, at least at first. One of the interesting things is that as local teams are starting to see the value of women’s empowerment, we’re finding that they have begun taking on their own women’s empowerment initiatives. For example, at least one aggregator has begun working with a group of women to help them get access to land.

What are some important inclusive approaches that you’ve woven into the partnership?

Corinne: One important lesson we have learned has been to not be afraid to advocate for a gender-transformative approach. We want women to have access to land and to be farmers in the supply chain; we want men to recognize women as farmers and for women to identify as farmers. PepsiCo has been very receptive to testing a transformative approach. Additionally, preventing and responding to gender-based violence [GBV] is a central tenet of this activity. Some of the GBV interventions in West Bengal have included partnering with local organizations that provide survivor-centric support. [The United Nations defines a survivor-centered approach as one which seeks to empower the survivor by prioritizing their rights, needs and wishes.] We trained the local PepsiCo teams on what to do when they encounter GBV and gave them concrete steps to take.

Sarah: PepsiCo was very responsive to the inclusion of GBV prevention and response initiatives. As this was the first time focusing on gender equality and women’s empowerment as a business performance driver, some of our partners at PepsiCo were surprised that we’d have to be careful of any potential backlash against women from a program that is focused on women’s empowerment. As we’ve developed the partnership, however, PepsiCo has been very attentive and at times has worried we weren’t doing enough on GBV. Seeing PepsiCo global and local staff take on the responsibility to think about and program for GBV has been inspiring.

What makes a partnership with a private sector actor successful?

Sarah: Keeping clear lines of communication open to be able to discuss any issues transparently and collaboratively, particularly around any tension points that arise, has been really important. That has also been very effective for learning.

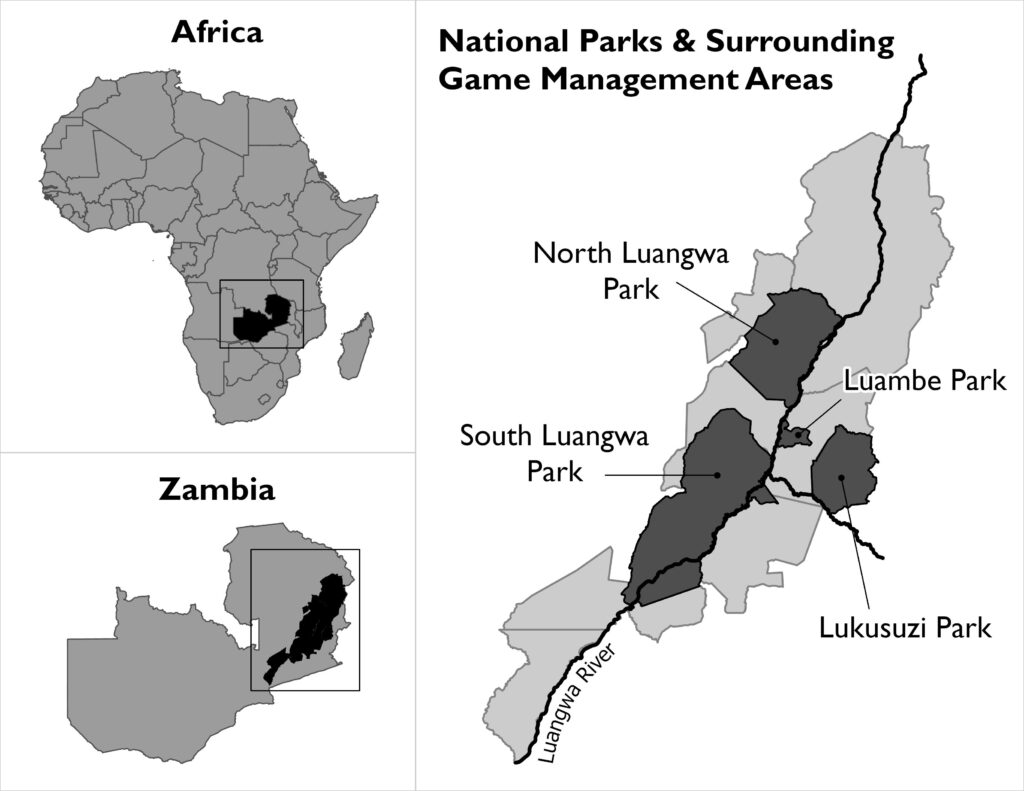

The valley is also home to 70,000 people and over 4,500 settlements in five customary chiefdoms, a population that has tripled over the past forty years. The chiefdoms are located in areas known as Game Management Areas, buffer zones to the national parks designed with the dual objectives that both wildlife and communities flourish. But these buffers are being pressured both by increasing wildlife populations, due in part to successful conservation efforts, and farmers. Each year, farmers prepare new tracts for agriculture, cutting deeper into habitats, within the current ranges and prime habitats of elephants and hippos, as well as predators.

The valley is also home to 70,000 people and over 4,500 settlements in five customary chiefdoms, a population that has tripled over the past forty years. The chiefdoms are located in areas known as Game Management Areas, buffer zones to the national parks designed with the dual objectives that both wildlife and communities flourish. But these buffers are being pressured both by increasing wildlife populations, due in part to successful conservation efforts, and farmers. Each year, farmers prepare new tracts for agriculture, cutting deeper into habitats, within the current ranges and prime habitats of elephants and hippos, as well as predators.

I am a senior agricultural specialist at USAID/Mozambique with more than 30 years of experience in agricultural development, including land rights and resource governance. I have an MSc in Animal Production from the University of Pretoria and an Honors degree in Veterinary Medicine from Eduardo Mondlane University.

I am a senior agricultural specialist at USAID/Mozambique with more than 30 years of experience in agricultural development, including land rights and resource governance. I have an MSc in Animal Production from the University of Pretoria and an Honors degree in Veterinary Medicine from Eduardo Mondlane University.

My name is F. Mulbah Zig Forkpa, Jr. I am currently the Land Governance Specialist at USAID/Liberia. I have served in this capacity for five years, helping to implement the Mission’s land and resource governance programs-first the Land Governance Support Activity, a $15.6 million activity which ended in August 2020, and now the Land Management Support Activities, a $9.4 million activity which continues until 2025. I also serve as one of the focal persons on gender in the Mission’s Office of Democracy, Rights, and Governance. I am a proud graduate of USAID’s inaugural

My name is F. Mulbah Zig Forkpa, Jr. I am currently the Land Governance Specialist at USAID/Liberia. I have served in this capacity for five years, helping to implement the Mission’s land and resource governance programs-first the Land Governance Support Activity, a $15.6 million activity which ended in August 2020, and now the Land Management Support Activities, a $9.4 million activity which continues until 2025. I also serve as one of the focal persons on gender in the Mission’s Office of Democracy, Rights, and Governance. I am a proud graduate of USAID’s inaugural