Q&A with three rural women from Tolima about claiming their land rights and inspiring women in their communities.

This blog was originally published by Land for Prosperity.

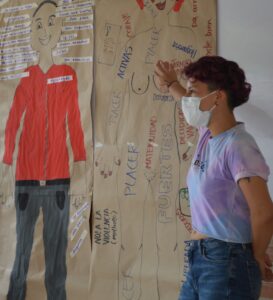

As part of the massive land formalization campaign in Ataco Municipality, Tolima, USAID Land for Prosperity Activity joined Colombia’s Land Restitution Unit (URT) to deliver a series of workshops to empower rural women ranging in age about property rights, land ownership, the care economy, and gender-based violence.

The women, who are involved in land restitution and formalization processes, will then replicate the knowledge with other women from their communities. In this interview, the following three women talk about their experience:

- Jimena Gutiérrez, 18, is finishing high school and works as a guard for the Mesa de Pole indigenous community.

- Laura Sanabria, 26, is a feminist and sociology student, an activist, and the leader of the Ataicamas Santiago Perez youth organization.

- Aracely Montano, 56, is a mother, housewife, and for the two years has been involved in a land restitution process.

Why do you think these empowerment workshops are only for women?

Aracely: Our gender has been abandoned, and they don’t listen to us. Because of sexism, men are always the ones who lead and make decisions.

Jimena: So that women are empowered and fight for their rights. Women’s rights are constantly being violated, and these spaces highlight how women are also capable, just as much as men.

Which do you think is the biggest obstacle that women face in their communities when it comes to expressing their rights?

Aracely: Because of sexism we have never been heard, men are always saying that they are the only ones that can work or start a project, and we can’t. They always say: “You? Who is going to listen to you? Leave it to us men.”

Laura: The biggest obstacle here is the ignorance of the population. Most institutions are centralized in the department’s capital, even though Ataco has 107 villages and most of the population lives in rural areas.

How can women begin to overcome these obstacles?

Jimena: Working together as women, because honestly, there is very little that one can achieve alone. But if we come together to fight for our rights and for ourselves, we can show people that we are capable and we can achieve what we put our mind to, we can change the law.

Laura: We need government institutions to come closer to our rural territories, to be present in the villages and reach the communities. We need strategies like this one. The government needs to reach small villages, visit the people, promote the roels and responsibilities of each entity, and tell us how we can access services related to gender and youth policies.

What benefits do you see for women who participate in these workshops?

What benefits do you see for women who participate in these workshops?

Laura: Even though the main topic is rural property, several subjects that reach beyond land titling and restitution have emerged. These spaces have enhanced the ability of women to recognize gender-based violence, to recognize the fundamental work that they fulfill when it comes to caring for their homes and society at large; and especially to understand that the women’s work has not been valued as it should be, that women are instead invisible. The workshops have also taught us about self-care, because knowing about the dynamics of gender based violence allow us to create strategies to take care of ourselves, to decide that we do not want to experience this violence, and question certain practices that were once seen as normal.

The Land for Prosperity Activity created gender and social inclusion guidelines for the implementation of massive formalization efforts that focus on increasing the knowledge of women about land rights and the care economy. In Ataco, this includes a municipal commitment to guarantee the inclusion and participation of women, youth, and ethnic communities in all phases of land formalization.

The massive land formalization campaign, funded by USAID in partnership with the government, has reached and trained nearly 600 people in Ataco, of whom nearly half are women.

What has been the most important lesson that you have learned during the workshops?

Jimena: The workshop has highlighted our rights and taught us to fight for ourselves and support each other. There is a lot of criticism between women, but here they teach us to join forces and work together. As far as land ownership, even though we do not have the documents for the land we live on, there is a chance that it will be ours and the land title will have our names on it. We have been living there for over 10 years, this is the opportunity to have a home of our own.

What does the term “empowered woman” mean to you?

Aracely: A woman who wants to move forward, a fighter, an entrepreneur, who starts her own projects, goes out, interacts with different people and projects, knocks on doors, asks for help, and in this way brings her village and her family forward.

How does empowerment result in women stand up for their rights?

Laura: We need to stop and reflect and understand what’s wrong. Once we know our rights, we can begin to question unhealthy practices that damage women, and raise our voices and fight for our land rights. Until we understand that, our capacity to demand our rights is non-existent because we will be unsure. We need to empower women with knowledge so they can raise their voices.

How do you plan to replicate this knowledge with your communities?

Ximena: We have monthly meetings with the women from my indigenous reservation, so there I will replicate what I have learned, so that women can understand their property rights.

Aracely: In my village, Pueblo Nuevo, I will share with all women who want to participate in social programs.

Laura: I am part of an organization called Ataicamas, and we were already thinking of hosting gender workshops. We want to start organizing workshops for women, especially about empowerment and economic independence.

About the author:

About the author: