This post is written by the Integrated Land and Resource Governance (ILRG) team and originally published in Agrilinks.

On March 8, 2021, International Women’s Day (IWD) marks a day where people across the world celebrate women’s achievements, raise awareness against bias, and take action to forge a more gender-inclusive world. USAID and PepsiCo recently partnered in West Bengal, India to support women in the PepsiCo potato supply chain in an effort to equalize their access to essential resources as their male counterparts, which is critical to agricultural success.

The USAID-PepsiCo partnership is designed to engage women as critical partners by empowering them, and thus challenging and transforming prevailing gender norms in the region, to build greater resilience in these rural farming communities and improve yields and performance in agricultural supply chains.

In West Bengal, India women are rarely seen as farmers, even though they typically spend as much time as their husbands working on the farm: preparing fields, planting seeds, harvesting crops, and managing animals.

When Anwara Begam and her women’s group, Eid Mubarak, were approached in October 2019 by the staff of a new joint initiative funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and PepsiCo to participate in potato farming as lead farmers, the group enthusiastically jumped at the chance. This was the first time many of these women had the opportunity to participate in agricultural extension; they received training and knowledge on a broad range of topics to apply to their agricultural practices to increase their yields and productivity. Through the support of this partnership, the group participated in a land-leasing activity to identify land and negotiate leasing terms; it was the first time many of these women had ever accessed farmland on their own.

With reliable land access, Anwara Begam and the women in the group attended agronomy training, improved their skills in potato farming and financial literacy, and became formal contributors to the PepsiCo potato value chain. During extension training sessions, Anwara learned how to improve her crop yields through land preparation, seed treatment, soil health and nutrition management, and pest and disease control. In its first year, the USAID-PepsiCo initiative conducted technical training with 48 women’s groups, bringing over 500 women into PepsiCo’s supply chain.

Using information from the agronomy training, Anwara recently recognized the signs of potato blight on her family’s farm and knew what measures to take to prevent it from spreading; however, her husband initially did not believe her. While he questioned her knowledge, she advocated that their family take swift action, and her initiative ended up saving her family’s crop.

Empowered with her enhanced skills and knowledge, Anwara is currently talking with other women about the positive benefits of improving women’s knowledge in agricultural practices, and at the same time, her bolstered ability to advocate and influence others has built her personal confidence and leadership skills.

Invaluable Women

The partnership’s initial success shows that empowering women with the knowledge, land, and access to PepsiCo’s value chain directly benefits the women and their families, while also meeting PepsiCo’s business goals to expand their supplier network and increase productivity.

PepsiCo agronomist Abdul Alim attended gender sensitization workshops and discussions on the role of women in agriculture alongside over 30 other PepsiCo staff. In his native village of Bhagaldighi, West Bengal, Abdul and PepsiCo aggregators have already hired women to sort and grade potatoes—jobs typically done by men.

Since Abdul’s training, seven women with experience growing PepsiCo potatoes participated in sorting and grading opportunities, where each worker can earn up to $4 per day. This pay is more than twice what a woman makes in an eight-hour day as an agricultural laborer, and the job offers women more flexibility to work around their household responsibilities, as they are paid on output rather than the number of hours worked.

Since the partnership began in mid-2019, USAID and PepsiCo have provided potato agronomy training for more than 1,000 women, as well as gender equality and women’s empowerment training to all PepsiCo local staff in West Bengal. From the partnership’s initial gender assessment, it was clear that economically empowering women requires more than teaching improved farming practices. Building on the success of the first year, the partnership will begin implementing household and community level dialogues on gender norms that hinder women’s access to and control over resources and income and further recognition of their role as farmers. Interventions that aim to change harmful gender norms, strategically engage men and community leaders, and increase women’s personal agency and empowerment are critical to mitigating unintended consequences, including gender-based violence.

Reporting from the field has shown that for Anwara Begam and the women of the Eid Mubarak group, access to land and knowledge provided by the USAID PepsiCo partnership led to increased self-confidence and recognition from their community, and they now see themselves as valuable potato farmers who contribute to their families’ livelihoods and the PepsiCo supply chain. This demonstrates that empowering women makes social and economic sense both for businesses and for rural communities.

Scaling through PepsiCo Agricultural Value Chains

Building on this initial success in West Bengal, PepsiCo and USAID are expanding the partnership through a Global Development Alliance (GDA) focused on proving the business case for women’s economic empowerment in Colombia, Pakistan, and Vietnam, and further into India in Uttar Pradesh.

The GDA will target PepsiCo farming communities with a gender-transformative approach that tests and pilots women’s economic empowerment solutions on PepsiCo demonstration farms, as well as scales up promising practices demonstrated in the initial project in West Bengal. The partnership aims to ensure that women farmers and workers benefit from being directly or indirectly involved within PepsiCo’s supply chains while also being empowered within their households and communities. Integrating women’s economic empowerment into PepsiCo’s sustainable agriculture approach will strengthen livelihoods and community resilience while improving the performance and sustainability of the supply chain.

PepsiCo will use data and insights from this partnership with USAID to show that investing in women makes business sense and should be scaled within PepsiCo’s supply chains and adopted by other leading companies. Read more about our work in West Bengal here and the GDA here.

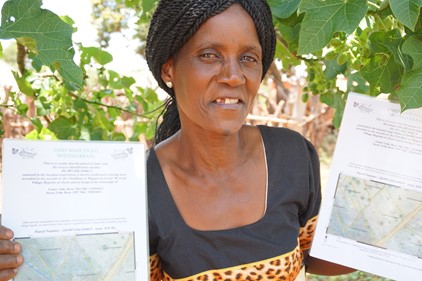

Like in many chiefdoms across Zambia, tradition dictates that family care corresponds to women leadership corresponds to men. As a result, men dominate both the household and community-level decision making when it comes to natural resources. In Chikwa, however, the Chief sees a role for women in natural resource management as a way to advance development in his chiefdom. He is willing to challenge traditions in order to secure opportunities for women leaders.

Like in many chiefdoms across Zambia, tradition dictates that family care corresponds to women leadership corresponds to men. As a result, men dominate both the household and community-level decision making when it comes to natural resources. In Chikwa, however, the Chief sees a role for women in natural resource management as a way to advance development in his chiefdom. He is willing to challenge traditions in order to secure opportunities for women leaders.