Strong and meaningful land tenure begins with national, regional and local government coordination.

Voices of Local Leaders

Colombia’s bureaucratic public administration system is an obstacle for rural municipalities to connect with the national government, especially in the poorest and most conflict-affected regions. Communication and administrative bottlenecks prevent much needed funding from reaching Colombia’s most vulnerable, underdeveloped areas and hamper the implementation of Territorial Economic Development Plans (PDET), a key tool to boost investment and development in these regions, which also honors commitments for comprehensive rural reform in the 2016 Peace Accord.

“Let’s Click” for the PDET —an initiative created by USAID, the Agency for Territorial Renewal (ART) and the Presidential Counselor for Stabilization, Emilio Archila— seeks to link local priorities with national resources and relevant cooperation programs funded by USAID. It also helps streamline support to avoid redundancy and increase the efficiency of investments.

Last year, USAID’s Land for Prosperity Activity participated in Let’s Click meetings with ART regional officials and elected leaders from several municipalities: The Mayor of Tumaco, 11 municipalities in Catatumbo, 15 in Montes de María, 4 municipalities in Southern Tolima and the Governor of Sucre.

In a meeting with municipal leaders of Southern Tolima, USAID presented its activities and offered technical assistance which aligns with the priorities and needs expressed in their PDETs. Public officials proved eager to continue coordinating with USAID, picking up where past initiatives have left off, such as in land tenure, government strengthening, and tertiary roads.

The mayors from Ataco, Planadas, Chaparral, and Rioblanco also presented USAID-funded tertiary road inventories to the Ministry of Transportation. The ministry is currently selecting the priority tertiary roads to receive attention and funding. USAID is also partnering the the ART to improve private public partnerships in the coffee and cocoa value chains in Southern Tolima.

“We see the PDET territorial approach as the ideal long term solution to consolidate peace in Colombia because of the government’s will to push projects forward”

“We see the PDET territorial approach as the ideal long term solution to consolidate peace in Colombia because of the government’s will to push projects forward”

-Lawrence Sacks, USAID Mission Director in Colombia

The mayors of rural PDET municipalities agree that strengthening land tenure and property formalization are key drivers of stabilizing their territories. Over the past five years, PDET communities have continually requested improved land administration in order to update rural land cadasters and issue property titles. Multipurpose cadaster programs designed with USAID support and led by Colombia’s National Land Agency have become the roadmaps that align all levels of government, build the capacity, and inform the community.

In 2019, Colombia’s President Ivan Duque set lofty goals for supporting land policies and updating the country’s rural cadaster. Today a little more than 20% of the country’s cadaster is updated, and the government aims to reach 60% by 2022 and 100% by 2024.

“The Ovejas Pilot (massive land formalization) is proof that land titling, property, financial inclusion, and agriculture strengthening programs can be a reality.”

-Iván Duque, President of Colombia

For the better part of the past four years, USAID has harmonized inter-institutional coordination and partnerships with the National Land Agency (ANT), the Agustin Codazzi Geographic Institute (IGAC), the Superintendence of Notary and Registry (SNR), the National Planning Department (DNP), municipality leaders, and communities.

Land titling serves to transform the local economy by strengthening state presence, triggering public and private investments, and providing local governments with tools for land use and administration. On an individual level, land titling is the first step toward land security and citizen property rights, decreasing people’s vulnerability to displacement. A property title also allows farmers to access subsidies and financial services.

Land for Prosperity visited

Land for Prosperity visited

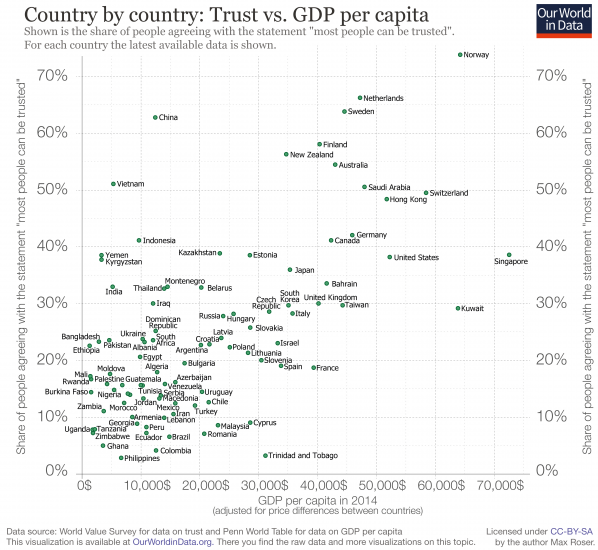

You’ll find many Sub-Saharan African countries crowded in the bottom left side of the graphic.

You’ll find many Sub-Saharan African countries crowded in the bottom left side of the graphic.

Working Together

Working Together

Is informality of public lands an obstacle to mobilizing resources that can be invested in infrastructure for public services, such as, health centers?

Is informality of public lands an obstacle to mobilizing resources that can be invested in infrastructure for public services, such as, health centers?