Gender-based violence (GBV) is estimated to affect more than one in three women worldwide. GBV takes a variety of forms, including sexual, psychological, community, economic, institutional, and intimate partner violence, and in turn affects nearly every aspect of a person’s life, including health, education, and economic and political opportunities. At the same time, environmental degradation, loss of ecosystem benefits, and unsustainable resource use are creating complex crises worldwide. As billions of people rely on these natural resources and ecosystems to sustain themselves, the potential human impacts are dire, with disproportionate effects on women and girls.

USAID’s Office of Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment (GenDev) is hosting the RISE Challenge to seek the innovative application of promising or proven interventions to address GBV in environmental programming.

THE RISE CHALLENGE AIMS TO:

- Spur greater awareness of the intersection between environmental degradation and GBV

- Test new environmental programming approaches that incorporate efforts to prevent and respond to GBV

- Widely share evidence of effective interventions and policies

- Elevate this issue and attract commitments from other organizations, including implementing partners and donors, for collaboration and co-investment

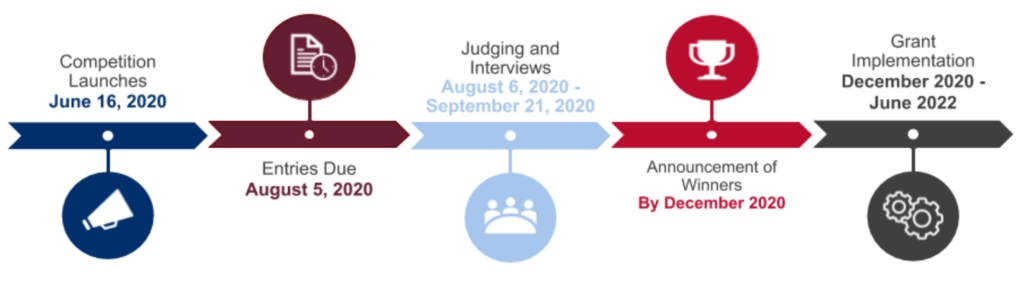

TIMELINE:

ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA:

ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA:

Prospective competitors must meet the following requirements to participate in the RISE Challenge. All applications will undergo an initial eligibility screening to ensure they comply with the eligibility criteria.

Organization size and type: RISE is open to all organizations regardless of size and type.

Partnership model: Applicants must demonstrate a partnership model and/or teaming intervention that leverages the capacity, expertise, and existing relationships across relevant environmental sector organizations, gender and GBV organizations, relevant experts, and local communities.

Local presence: All applicants must use the funds to implement interventions in geographies where USAID currently operates.

Willingness to capture and share evidence and learning: All applicants need to describe a clear and actionable plan for Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning that articulates how the applicant will test hypotheses, generate evidence, and use learning to adapt programming, which will feed into the evidence base that USAID is creating.

Topical: Applicants should present interventions that address the objectives of the Program Statement in the Request for Applications.

Gender analysis: Applicants must be willing to use grant funding to complete a gender analysis of their proposed intervention before implementation.

Eligible to receive USAID funds: RISE will conduct a responsibility determination prior to award, to ensure the applicant has the organizational and technical capacity to manage a USAID-funded project.

Language: Applicants must submit their entries in English.

Completeness and timeliness: Entries will not be assessed if all required fields have not been completed.

JUDGING CRITERIA:

Intervention rationale: Applicants will be judged on their articulation of the challenge, hypothesis for change, and rationale for how their intervention will prevent or respond to GBV in environmental programming.

Contextual awareness, human-centered approaches, and sensitivity: Applicants should describe and demonstrate an awareness of the local context in which their intervention operates, how they intend to meet their target population where they are at, and the measures in place to protect and collect sensitive information.

Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning: Given the nascency of the evidence base at this nexus, applicants will be judged on how their proposal will advance the international community’s understanding of challenges and potential interventions at the intersection of GBV and environmental programming.

Innovative partnerships and organizational capacity: Applicants will be judged on the degree to which their partnership model demonstrates the ability to leverage the diversity of expertise required to successfully innovate new interventions to challenges at the intersection of GBV and the environment. This includes proposed engagement with GBV organizations, women’s and girls’ organizations, indigenous communities/groups, youth, and other vulnerable groups and local partners. Partnerships with research, academic, or evaluation organizations with the capacity to support evidence collection are also highly encouraged.

Pathway to integration: Applicants should demonstrate a plan for understanding how this intervention can be applied in new contexts beyond the initial application.

Deadlines, details, and application:

competitions4dev.org/risechallenge Contact us: rise@usaid.gov.

Engage: #USAIDRISE.