USAID Press Release

Wednesday, July 10, 2019

Today, U.S. Agency for International Development Administrator (USAID) Mark Green and Ivanka Trump, Advisor to the President, announced 14 new projects with more than 200 public- and private-sector partners across 22 countries to support the Women’s Global Development and Prosperity (W-GDP) Initiative. These partnerships, which include representatives from bilateral and multilateral donors, non-government organizations, universities, foreign governments, and the private sector, will enable W-GDP to reach more than 100,000 women over the coming years in support of its three pillars: women prospering in the workforce, women succeeding as entrepreneurs, and women enabled in the economy. The announcement took place in front of hundreds of partners and award recipients in an event co-hosted with the U.S. Global Leadership Coalition.

Administrator Green noted “we know that investing in women builds countries that are resilient and self-reliant. The Women’s Global Development and Prosperity Initiative will accelerate the achievement of these goals by leveraging the collective resources and expertise of the U.S. Government to unlock the full economic potential of women around the world.” Advisor Trump said “we are thrilled by the enthusiastic response since the launch of W-GDP. Through our three core pillars of women prospering in the workforce, succeeding as entrepreneurs, and advancing economic equality under the law, we are committed to delivering real results that create transformational change for women in developing countries.”

USAID manages the central W-GDP fund, established through National Security Presidential Memorandum-16, and has set aside $27 million for an Incentive Fund for the following projects:

- A Micro-Journey to Self-Reliance: Economic Reintegration for Victims of Gender-Based Violence: Reintegrate at least 170 women victims of gender-based violence into the economy through increased employment and entrepreneurship opportunities.

- Brazil, Chile, Colombia, México, and Perú. Women Prospering in Technology: Work with information and communications technology companies to equip 8,700 women with the skills needed for placement and promotion in tech sector jobs.

- Côte D’Ivoire. Pro-Jeunes Vocational Training for Women in Energy:Provide vocational training and support to 750 postsecondary young women in solar-energy sales, installation, and service as entrepreneurs and employees for solar-powered micro-grids.

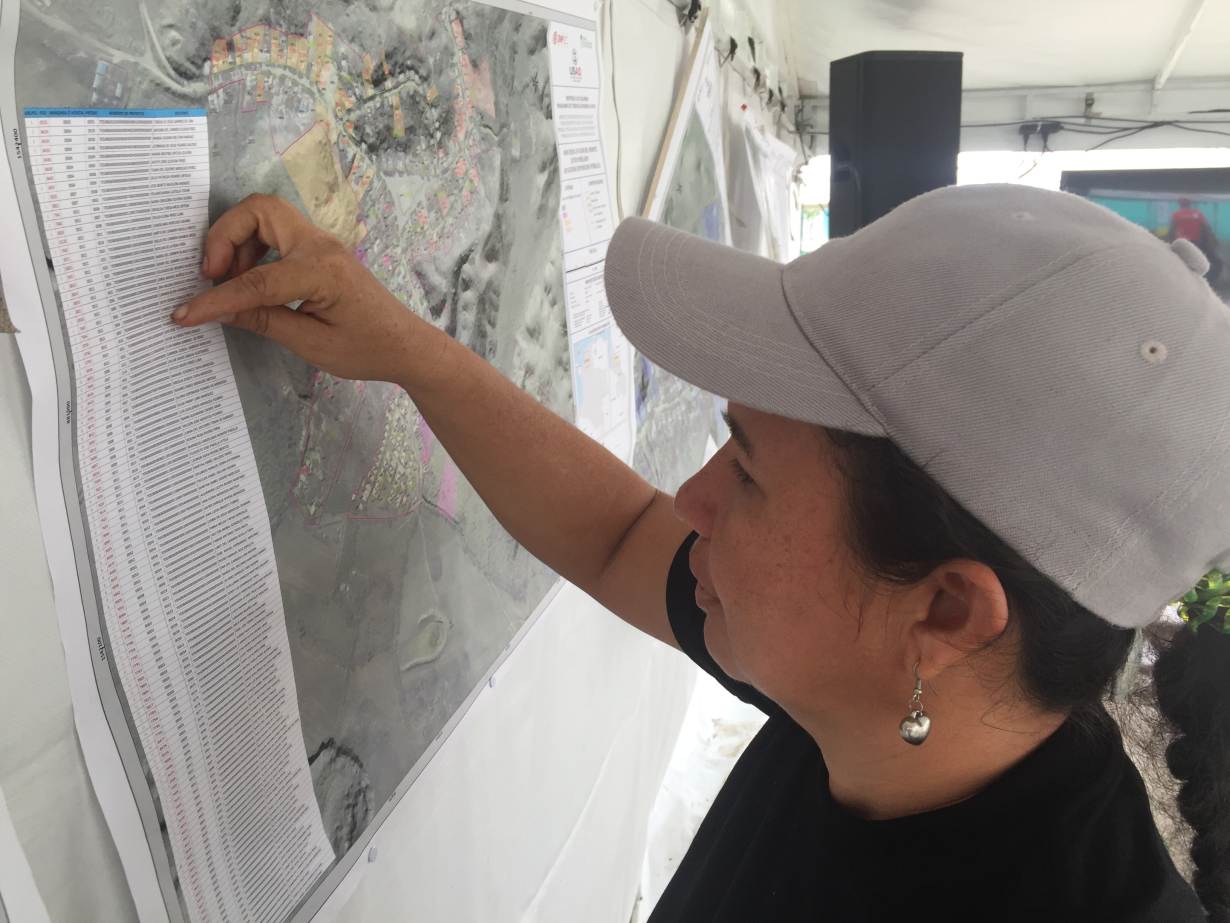

- Ethiopia, Liberia, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia. Property Rights for Women’s Economic Empowerment: Ensure women’s property rights through revising laws and regulations to improve the ability of millions of women to own, inherit, or use land across Africa.

- Supporting Entrepreneurial Skills (YES-Georgia): Provide focused technical assistance for 2,500 women entrepreneurs and employees to increase their earnings and facilitate access to finance for women entrepreneurs.

- USAID Global Development Alliance with Alaffia Alliance: Establish new processing operations in Ghana to create employment opportunities for 9,500 women in Ghana and link them with markets in the United States.

- Producer-Owned Women’s Enterprises: Create 28 women-owned enterprises in the creative manufacturing sector that will connect 6,800 women producers to commercial supply chains in natural and biodegradable products.

- Jadi Pendusaha Mandiri (JAPRI) – Becoming an Independent Entrepreneur: Create 2,000 registered women-owned enterprises and support growth in income and revenue for 5,000 women in poultry supply chains.

- Papua New Guinea. Women’s Economic Empowerment: Support the growth of 40 women-led enterprises while reforming discriminatory laws and business practices that affect 50,000 women in Papua New Guinea.

- The Philippines. The Journey to Self-Reliance through Women’s Economic Empowerment: Work with the private sector to increase earnings for 3,800 women entrepreneurs and 12,000 households, and assist local governments to address barriers that prevent women’s full economic participation.

- Women in Rwandan Energy (WIRE): Enable 1,400 women to break into the fast-growing energy sector, while working with the Rwandan Government and the private sector to bring even more women into this traditionally male- dominated field.

- Sénégal.Women’s Entrepreneurship Promotion and Business Investment Activity: Work with Peace Corps and the private sector to create 1,500 new jobs for women in agribusiness and equip 20,000 women with the necessary skills to increase their earnings.

- South Africa. Women Enabling Women: Create an eco-system of women’s economic empowerment by establishing 1,000 women-owned child-care centers, which will create jobs for thousands more women while reducing the burden of unpaid care for women in the workplace.

- West Africa.Women’s Economic Empowerment in the West Africa Trade and Investment Hub (WATIH): Ensure women-owned and managed Ghanaian agribusinesses will have greater access to markets for trade and investment.

The awarded projects will open doors to employment and entrepreneurship, and provide access to finance and tailored assistance for women in business. Moreover, the projects were carefully designed to target constraints found in laws, employer practices, and restrictive norms to improve the enabling environment for women employees, business-owners, and entrepreneurs for decades to come. The awarded projects were selected based on an interagency review process that included over 50 different points of contact who reviewed, rated, and ranked each proposal that was submitted. USAID looks forward to working with Congress in a bipartisan manner on these important initiatives.

Learn More

Additional Resources

The first whole-of-government approach to global women’s economic empowerment [download file]

“Investing in women is vital for our collective economic prosperity and global stability. When we empower women, communities prosper and countries thrive.”

IVANKA TRUMP, ADVISOR OF THE PRESIDENT

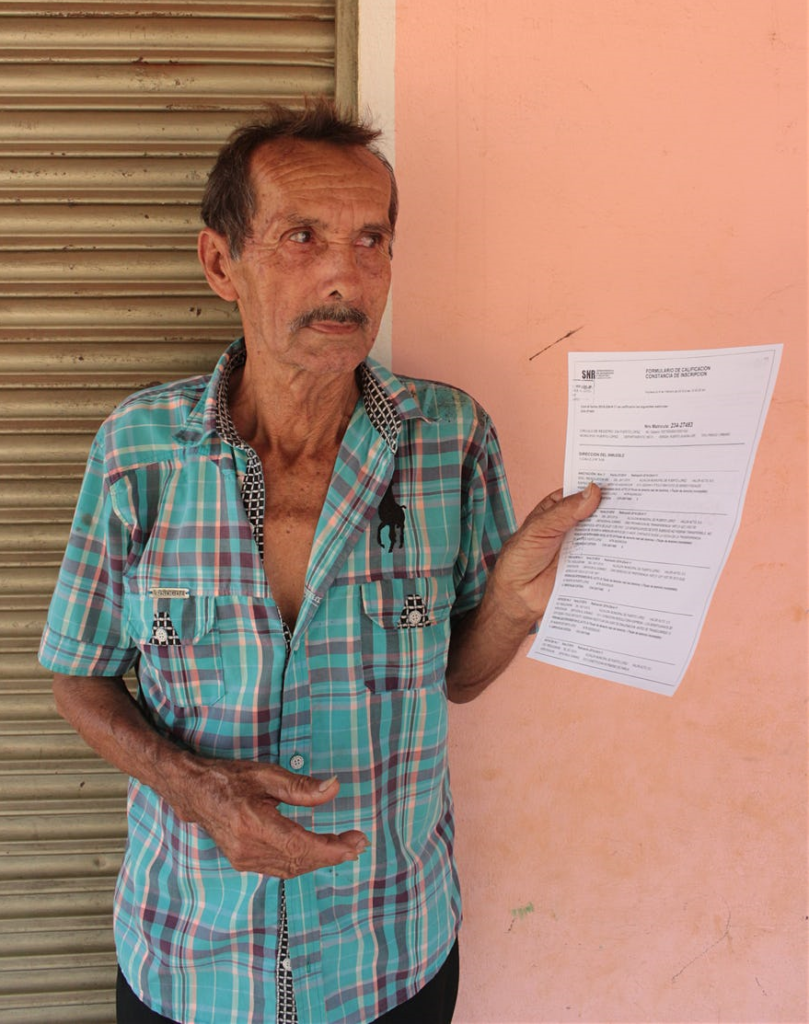

“When this government took over, less than 20% of the country had an updated cadaster. With USAID’s support and new public policy, the goal is to update the cadaster for 60% of the country by 2022, and try to reach 100% by 2024. The Ovejas Pilot in Ovejas is proof that land titling, property, financial inclusion and agriculture strengthening programs can be a reality.”

“When this government took over, less than 20% of the country had an updated cadaster. With USAID’s support and new public policy, the goal is to update the cadaster for 60% of the country by 2022, and try to reach 100% by 2024. The Ovejas Pilot in Ovejas is proof that land titling, property, financial inclusion and agriculture strengthening programs can be a reality.” Property Rights

Property Rights

Discussions about land tenure in

Discussions about land tenure in

Maritza Losada moved to Puerto Guadalupe, Meta five years ago when her husband found a job with a large biomass energy company that grows sugar cane. She and her husband purchased a lot in the town’s poorest neighborhood, Barrio Nuevo. The district remains today much like it was in 1995 when the government created the housing project for future agro-laborers: no roads, no sewage, no gutters.

Maritza Losada moved to Puerto Guadalupe, Meta five years ago when her husband found a job with a large biomass energy company that grows sugar cane. She and her husband purchased a lot in the town’s poorest neighborhood, Barrio Nuevo. The district remains today much like it was in 1995 when the government created the housing project for future agro-laborers: no roads, no sewage, no gutters.