By Terah U. DeJong, Country Director, Côte d’Ivoire, Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development (PRADD II) Project

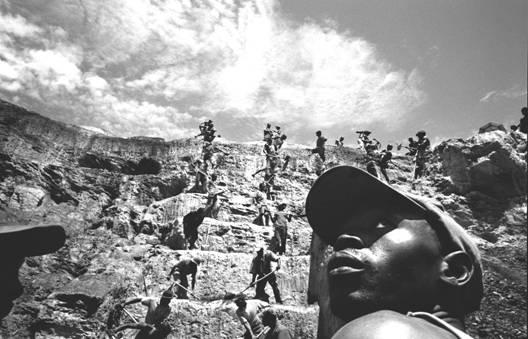

What is formalization in the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector? Reflections from the first international gathering dedicated to ASM in over a decade.

Formalization was a key buzzword at the International Conference on Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining and Quarrying (ASM18) held Sep 11-13 in Livingstone, Zambia. But what does formalization really mean in practice?

In my remarks at the event, I tried to unpack the concept based on my experience running USAID’s Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development (PRADD II) project in Côte d’Ivoire over the last five years, offering the following definition:

ASM formalization is the process of collaborative rule-setting and rule enforcement across supply chain actors, governments and communities with the aim of enabling ASM to contribute to local and national peace and prosperity, both now and for future generations.

By thinking of formalization in this way, we avoid just counting licenses and miner cards, and instead look at the degree to which governments, communities, miners and buyers have a productive and collaborative relationship. This relationship must be built on a shared understanding of the legitimate role of ASM in national and local economies, and a shared strategy to regulate and promote it.

Here are 5 ways in which PRADD II tries to apply this in practice.

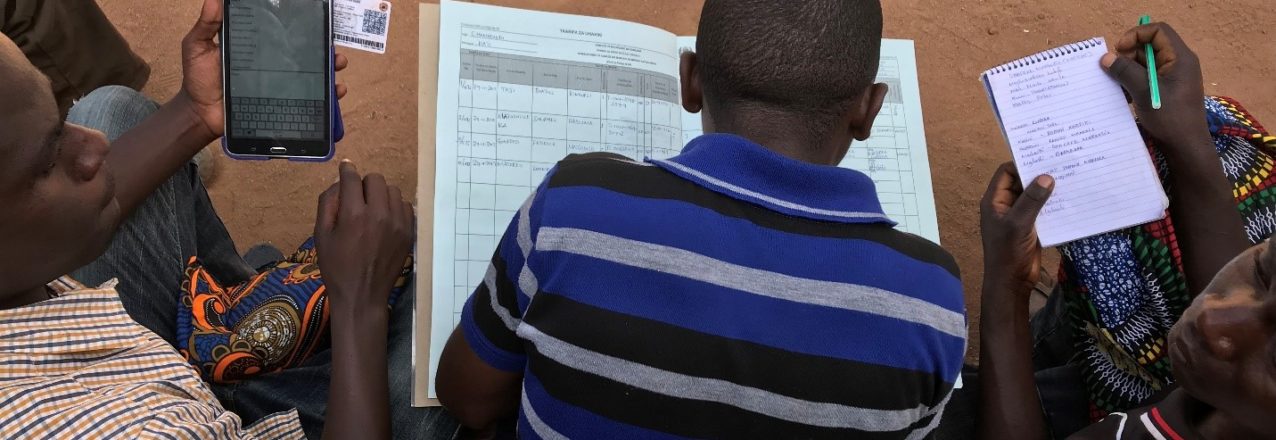

- First, we emphasize the need to develop a deep and accurate understanding of ASM supply chains – who are the miners, who are the buyers, what are differences between them, what power dynamics mark their relationships, how are they socially embedded, who are their leaders… the list goes on. Learning must be ongoing, analytical and participatory.

- Second, PRADD II sees collaborative and multi-level policy-making as key. By this we mean an inclusive process to define the vision, objectives and systems that will manage and promote ASM. The resulting policy must reflect the compromises and consensus about tough issues like licensing categories and revenue-sharing. Then, and only then, can resulting laws and regulations be realistic.

- Third, PRADD II fosters structured dialogue between all actors to build trust, share information and make necessary adjustments to rules and their enforcement. It is surprising how often actors do not talk to each other and, thus, creating spaces for dialogue is key. And it’s important to recognize that it isn’t just governments who make the rules – communities make rules, buyer networks make rules, diggers make rules. Dialogue is the only way to ensure that these rules are in harmony and effectively implemented.

- Fourth, PRADD II works on awareness-raising and norm-setting, so that actors have shared knowledge and a shared understanding when it comes to ASM and common challenges. Increased knowledge is beneficial not just to help actors comply with the laws, but also because it creates a shared “language.” For example, when miners and buyers both understand the principles of diamond valuation, conflict is reduced.

- Fifth, PRADD II focuses on incentives – both positive and negative – to make sure everyone remains involved and committed. In Côte d’Ivoire, communities have a big incentive – a 12% tax that they take on the value of the first sale – to record production and ensure the diamonds pass through the mining cooperatives. PRADD II introduced technical assistance measures as incentives to miners. Of course, incentives must be carrots and sticks. The project encouraged authorities and communities to enforce their rules, fairly and equitably, as without consequences there is little reason to comply.

ASM18 was a great forum to share PRADD II experiences and learn from the hundreds of others working on the “formalization agenda”. With a clear vision and clear strategies to achieve formalization, the decade ahead bodes well for ASM, increasing the chances that it will truly live up to its development potential.

Click here to watch the videos for the PRADD II Program