Dr. Matt Sommerville is the chief of party of the USAID Tenure and Global Climate Change (TGCC) program, which has implemented research and pilot activities to improve sustainable land management through strengthening land and resource rights. The program was active in Zambia, Burma, Vietnam, Ghana and Paraguay. From 2014 to 2017, Sommerville was based in Zambia, backstopping a customary land certification process that resulted in the documentation of over 15,000 parcels of land across five chiefdoms in Zambia’s Eastern Province.

Dr. Matt Sommerville is the chief of party of the USAID Tenure and Global Climate Change (TGCC) program, which has implemented research and pilot activities to improve sustainable land management through strengthening land and resource rights. The program was active in Zambia, Burma, Vietnam, Ghana and Paraguay. From 2014 to 2017, Sommerville was based in Zambia, backstopping a customary land certification process that resulted in the documentation of over 15,000 parcels of land across five chiefdoms in Zambia’s Eastern Province.

Tell us about the Tenure and Global Climate Change project in Zambia.

USAID began supporting customary land documentation in Zambia to test a simple question: Does the documentation of land rights influence farmers’ decision to adopt sustainable farming practices? The intervention was designed as a randomized control trial impact evaluation, and includes almost three hundred villages that were split between four treatment groups: one that participated in a land-tenure-strengthening intervention, a second that participated in an agroforestry intervention, a third that participated in both land tenure and agroforestry interventions and a control group.

As TGCC began to work with local chiefs, it became apparent that there was national interest across Zambia, from chiefs, civil society, and the Ministry of Lands, in low-cost, mobile technology-based, robust processes to document the land rights of Zambia’s millions of landholders. With the Urban and Regional Planning Act of 2015 and the Forest Act of 2015, new opportunities emerged for coordination between state and customary leaders on land use planning and resource management. Based on this, USAID began supporting civil society partners to undertake land documentation at scale. In addition, we also worked across interest groups to build communication and transparency between chiefs, communities and government ministries to improve land and resource management.

Why is this work important?

Zambia has historically been a large land area / low population country and land has been perceived as abundant. However, since liberalizing land markets in the mid-1990s, demand for land has skyrocketed, both from large-scale investments, as well as from middle and upper-class Zambians looking to access small farms in Zambia’s rural customary land.

Zambia’s centralized land record system is incomplete on government administered leasehold land, and is non-existent in the majority of the country under customary management. Incomplete records alongside limited transparency or communication between customary and state systems has created conflicts, disadvantaged women who lack documentation of their rights, reduced economic investment from the private sector, and robbed government of tax revenue.

Customary land documentation and increased transparency between the state and customary systems and presents a solution to the above challenges. With more complete land records and tax systems, the Ministry of Lands can contribute to the national Treasury. With the clarity of land allocations and existing customary rights on land, communities and district councils will be able to undertake land use planning, particularly in peri-urban customary areas, which will subsequently inform private investors, and reduce risks of conflicts related to their developments.

What are key achievements/successes from TGCC’s work in Zambia?

TGCC has contributed significantly to opening up communication among government, civil society, donors, chiefs and communities on land issues, and created opportunities to find common objectives. Through this process, TGCC has supported over thirty consultations across the country on Zambia’s draft land policy, which has evolved significantly over the past three years as a result and is expected to be sent to Cabinet in 2018.

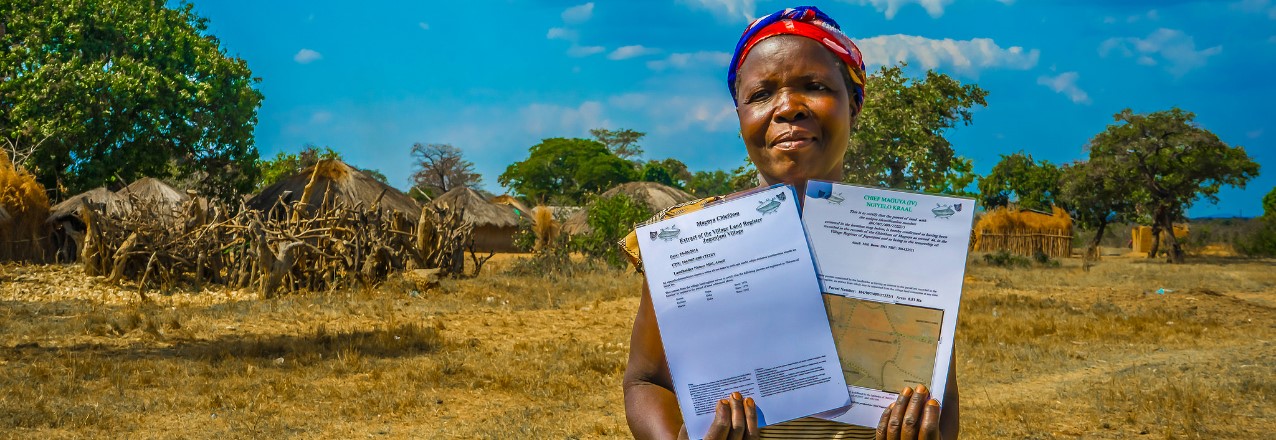

TGCC’s support to the Petauke and Chipata District Land Alliances, local civil society organizations, has demonstrated the ability of civil society organizations to play an active role in delivering land-administration services, acting as an honest broker between chiefs, communities and the district government. Through this work, the two district land alliances have mapped over 15,000 land parcels and documented individuals with ownership and other interest rights in that land. Nearly half of the parcels have a female landholder associated with the parcel, representing equal rights of ownership over the land.

Zambia’s government accepted these customary land parcels into the same national spatial data infrastructure that houses state land. For the first time, this allows the general public to see customary and state land allocations together.

Based on business as usual, the task of documenting the land rights across of Zambia’s land surface would take over 1,000 years. USAID’s participatory process and mobile tools developed under TGCC could bring this work down to under a decade. However, the costs would be substantial. To address this, TGCC has helped coordinate donor engagement with government and among each other to leverage investments in the land sector, and develop tools that can be cost-effectively replicated by government.

With respect to the impact evaluation goals of the program (testing how stronger property rights affect a farmer’s decision to practice climate-smart agriculture, including agroforestry), evaluators found success in each intervention. In terms of strengthening tenure security and increasing investment in agroforestry practices, however, the interactions among the two are more ambiguous. TGCC found some evidence that households with secure land rights invested more in some sustainable land-use practices and that women with secure land rights were marginally more engaged in agroforestry adoption. Indeed many factors go into the decision to adopt sustainable land use practices. However, it is clear that land tenure impacts take time to be felt.

What were the key lessons learned?

- The process of carrying out customary land documentation can be as important or more important than the document itself, because it can help farmers identify and resolve their long-standing disputes, and involves jointly walking boundaries.

- Inter-ministerial coordination is essential to resolving land and resource governance disputes as no single ministry has complete authority over land and resources in an area.

- While mobile tools can support data collection and data entry, they do not replace the need for paper receipts and reference maps in the field.

- The social dimensions of building understanding of customary land certification processes and goals, and the use of local civil society partners for implementation is essential to build trust and partnerships from local communities.

Where can I find more information?

The Tenure and Global Climate Change program in Zambia developed an abundance of resources including:

- Films documenting the work on:

- aligning land-tenure activities with traditional land governance (forthcoming)

- women’s empowerment (forthcoming)

- the strength of partnerships (forthcoming)

- how land tenure helps promote better farming techniques (forthcoming)

- Fact sheets, research and briefs include:

These resources and more information about the TGCC program in Zambia can be found at Land-Links.org here.

Tao Van Dang has served as the activity manager for the Participatory Coastal Spatial Planning and Mangrove Governance project in Vietnam since 2015. With more than 20 years of project management experience, particularly in non-governmental organizations, Dang has overseen mangrove re-forestation and disaster preparedness projects throughout Vietnam.

Tao Van Dang has served as the activity manager for the Participatory Coastal Spatial Planning and Mangrove Governance project in Vietnam since 2015. With more than 20 years of project management experience, particularly in non-governmental organizations, Dang has overseen mangrove re-forestation and disaster preparedness projects throughout Vietnam.

Catherine (Kitty) Courtney has more than 25 years of international and domestic experience in marine and coastal management, climate change adaptation and coastal community resilience.

Catherine (Kitty) Courtney has more than 25 years of international and domestic experience in marine and coastal management, climate change adaptation and coastal community resilience.

Dr. Matt Sommerville is the chief of party of the USAID Tenure and Global Climate Change (TGCC) program, which has implemented research and pilot activities to improve sustainable land management through strengthening land and resource rights. The program was active in Zambia, Burma, Vietnam, Ghana and Paraguay. From 2014 to 2017, Sommerville was based in Zambia, backstopping a customary land certification process that resulted in the documentation of over 15,000 parcels of land across five chiefdoms in Zambia’s Eastern Province.

Dr. Matt Sommerville is the chief of party of the USAID Tenure and Global Climate Change (TGCC) program, which has implemented research and pilot activities to improve sustainable land management through strengthening land and resource rights. The program was active in Zambia, Burma, Vietnam, Ghana and Paraguay. From 2014 to 2017, Sommerville was based in Zambia, backstopping a customary land certification process that resulted in the documentation of over 15,000 parcels of land across five chiefdoms in Zambia’s Eastern Province.

Yaw Adarkwah Antwi has more than 20 years of experience in land tenure and administration policies and holds a Ph.D. in Sub-Saharan Africa Urban Land Markets and an M.A. in Property Valuation and Law. Antwi has helped to develop land policies, particularly on the topics of land tenure, land management and agricultural development, in Liberia, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and, within the COMESA region, Kenya and Sudan. Antwi is currently the country lead and senior land tenure expert on the Improving Tenure Security to Support Sustainable Cocoa project funded jointly by USAID and Hershey’s.

Yaw Adarkwah Antwi has more than 20 years of experience in land tenure and administration policies and holds a Ph.D. in Sub-Saharan Africa Urban Land Markets and an M.A. in Property Valuation and Law. Antwi has helped to develop land policies, particularly on the topics of land tenure, land management and agricultural development, in Liberia, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and, within the COMESA region, Kenya and Sudan. Antwi is currently the country lead and senior land tenure expert on the Improving Tenure Security to Support Sustainable Cocoa project funded jointly by USAID and Hershey’s.

Ryan Sarsfield is the Latin America commodities manager with World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch (GFW) team. He works to reduce the environmental impact of key commodities in Latin America through collaboration with corporate and NGO partners and the development of tools to reduce deforestation and supply chain risk.

Ryan Sarsfield is the Latin America commodities manager with World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch (GFW) team. He works to reduce the environmental impact of key commodities in Latin America through collaboration with corporate and NGO partners and the development of tools to reduce deforestation and supply chain risk.

As Burma Country Coordinator, Emiko Guthe managed Tenure and Global Climate Change (TGCC) project Burma pilot activities by helping to coordinate participatory mapping efforts, which documented community land resources in eight locations. A GIS specialist by training, Guthe brought her experience supporting mapping efforts to many international development projects in Burma.

As Burma Country Coordinator, Emiko Guthe managed Tenure and Global Climate Change (TGCC) project Burma pilot activities by helping to coordinate participatory mapping efforts, which documented community land resources in eight locations. A GIS specialist by training, Guthe brought her experience supporting mapping efforts to many international development projects in Burma.