“What will happen to my children and me if my husband and I get divorced?”

“If my husband dies, will I be allowed to stay in this land, or be chased by his relatives?”

“I am scared to tend to my crops at night, but what if security guards of the company who owns the land catch us? We have nowhere else to go.”

These fears about what tomorrow will bring are shared by rural women across the world. Women often live with land tenure insecurity, unsure about their long-term ability to access and control the land they depend upon to feed their families. Data from 140 countries show that one in five women worry it is likely or very likely they will have to leave their land against their will within the next five years.

Recognizing that secure land tenure is at the heart of rural women’s social and economic security, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is implementing innovative and comprehensive approaches to increase women’s ability to use land without fear. To reach remote rural areas on a large scale, USAID has pioneered Mapping Approaches to Secure Tenure (MAST), using participatory methods and mobile technology to efficiently, transparently, and affordably document land rights. MAST approaches have been used around the world, including to document over 100,000 land parcels in Tanzania and 40,000 in Zambia.

However, documentation isn’t enough. Women’s land security is much more complex than simply formalizing ownership on paper. As land management in many countries is still concentrated in the hands of men or customary kinship structures, most rural women access land through male relatives, leaving them economically dependent and vulnerable to gender-based violence. Even when women are able to own land, decision-making about its use and related income is usually controlled by men. USAID is partnering with communities, governments, civil society, traditional authorities, and the private sector to address the legal, institutional, and socio-cultural barriers that constrain women’s rights to own, inherit, use, and control land.

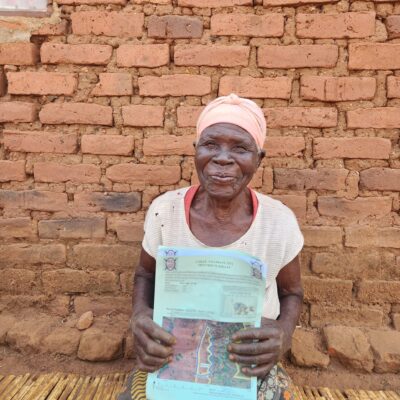

In Malawi, USAID worked with the government on a gender-responsive systematic land documentation project that included gender-balanced teams of enumerators, support for women elected to customary land committees, and household gender norms dialogues. These efforts were complemented by robust sensitization about women’s land rights through radio, comic booklets, and community gender champions going door-to-door. Lefas Dyson Moses initially registered a land parcel in his and his children’s names only. He left his wife of 50 years, Doris Joseph, out because he believed she had no claim to the land, having moved to his village upon marriage, a common view across Malawi. He changed his mind after speaking with the community gender champions and asked for the land certificate to be altered to include her. “I realized that I had made a grave mistake by not adding my wife as a landholder. She would easily be chased away from the land by my relatives in my absence, rendering her landless,” he reflected. Out of over 9,000 parcels registered so far, women are named in 67 percent of certificates, an impressive improvement from a previous pilot in the same area where women were named in only 38 percent of certificates.

As part of the effort to shift harmful gender norms hindering women’s land rights, USAID has worked with traditional leaders in Malawi and Zambia, given their central role administering customary land and acting as custodians of culture. USAID provided a space for local traditional leaders to reflect on harmful gender norms and identify how they can act as champions for change. Traditional leaders are now sensitizing community members about women’s rights to land, drafting by-laws banning widows being chased away from communities, and appointing women as village leaders. They are also leading by example, allocating land to women in their communities and registering their own land with their wives. According to Headman Kapachika from Zambia, “We are equal, so we should have equal rights to land. By giving land to women, we empower them, and they can support themselves now and in the future.”

USAID also partners with the private sector to implement innovative approaches to solve land conflicts between companies and rural communities and strengthen women’s land security. In Mozambique, thousands of smallholder farmers encroached upon land belonging to the agroforestry company Grupo Madal. Jubeda Mariano Mucufu, 35, remembers how the farmers used to work on the land at night, hidden, knowing that the land belonged to somebody else. Rather than evicting these farmers, Madal provided 1,300 people, 85 percent of them women, with long term land use rights. The women can now use the land for subsistence farming, as well as producing commercial crops for Madal. With the new income from participating in agricultural value chains for the first time, Jubeda is paying for school materials for her two children. “We really like the approach Madal is using, now we have peace of mind to work on our plot at any time of the day” she said.

Secure land rights and shifts in harmful gender norms are transforming fear into hope. When women can register land in their names, use land freely, and decide how land and income are used, they gain confidence and improved status in their households and communities. This in turn reduces conflict, opens pathways for economic security, and equips rural communities to better adapt to the effects of climate change.

“This is my land. Tomorrow when I am not here, nobody will take it from my children,” Vainess Ngoma, an 88-year woman from Muluso, Zambia, who registered two parcels of land with support from USAID.

The idea of a road and bridge across the Quilichao has been on the minds of city planners for at least twenty years but was never realized until a team of land experts from the Municipal Land Office took over the process of acquiring the land on both sides of the river.

The idea of a road and bridge across the Quilichao has been on the minds of city planners for at least twenty years but was never realized until a team of land experts from the Municipal Land Office took over the process of acquiring the land on both sides of the river.

That Wednesday morning, Soledid Rosillo, 48, woke up before the roosters, earlier than usual. She silently reviewed the list of her activities making sure not to wake anyone: prepare breakfast for her two children and her husband, pack a snack to take to school, iron school uniforms, clean the house…

That Wednesday morning, Soledid Rosillo, 48, woke up before the roosters, earlier than usual. She silently reviewed the list of her activities making sure not to wake anyone: prepare breakfast for her two children and her husband, pack a snack to take to school, iron school uniforms, clean the house…

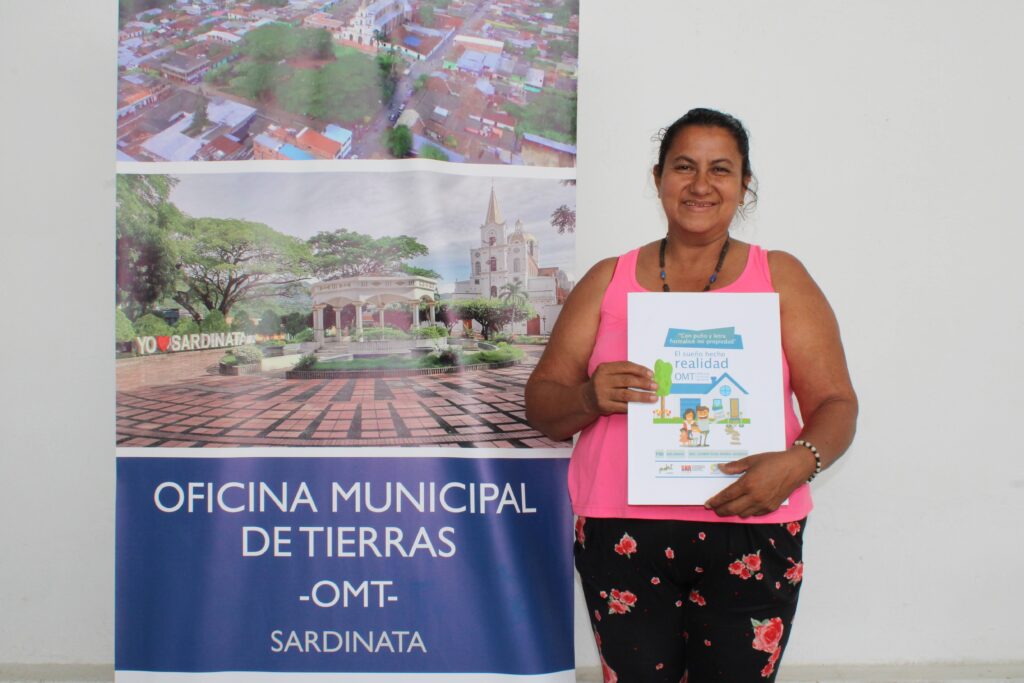

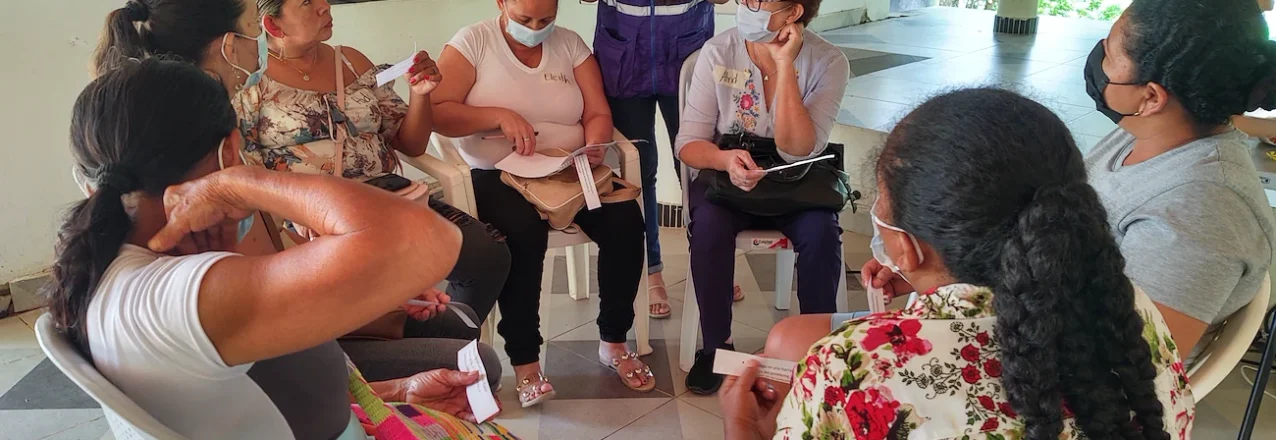

The municipality of Puerto Lleras (Meta) is one of 11 massive land titling initiatives being supported and promoted by the USAID Land for Prosperity program. In partnership with the Government of Colombia, these property sweeps update a municipality’s rural cadaster and title thousands of parcels. Each of the 11 parcel sweeps is focused on an entire municipality and seeks to ensure that rural women recognize their property rights, a key part of stimulating rural development and promoting a formal land market.

The municipality of Puerto Lleras (Meta) is one of 11 massive land titling initiatives being supported and promoted by the USAID Land for Prosperity program. In partnership with the Government of Colombia, these property sweeps update a municipality’s rural cadaster and title thousands of parcels. Each of the 11 parcel sweeps is focused on an entire municipality and seeks to ensure that rural women recognize their property rights, a key part of stimulating rural development and promoting a formal land market.