Overview

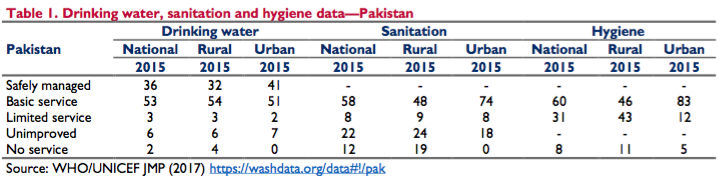

The landscape of Pakistan is highly varied, with mountains, deserts and the vast, irrigated Indus River Valley providing distinctly different productive opportunities for the population of nearly 208 million people. Combined access to land and water is critical to rural productivity. The densely-settled Indus Basin Irrigation System (IBIS) is the breadbasket of the country and produces the commodities that drive industry, with raw cotton and cotton textiles accounting for some 50–60 percent of exports. The Indus river basin is a resource shared with India, China and Afghanistan, with 47 percent of the IBIS land area is in Pakistan (FAO 2011b). The 1960’s Indus Water Treaty with India governs Pakistan’s access to water and maintains a precarious balance in an already water scarce region. Populations in the arid and semi-arid mountainous areas in the west and north of the country are more dispersed; farmers cultivating rainfed land known as barani rely upon smaller irrigation systems to support their crop and livestock enterprises.

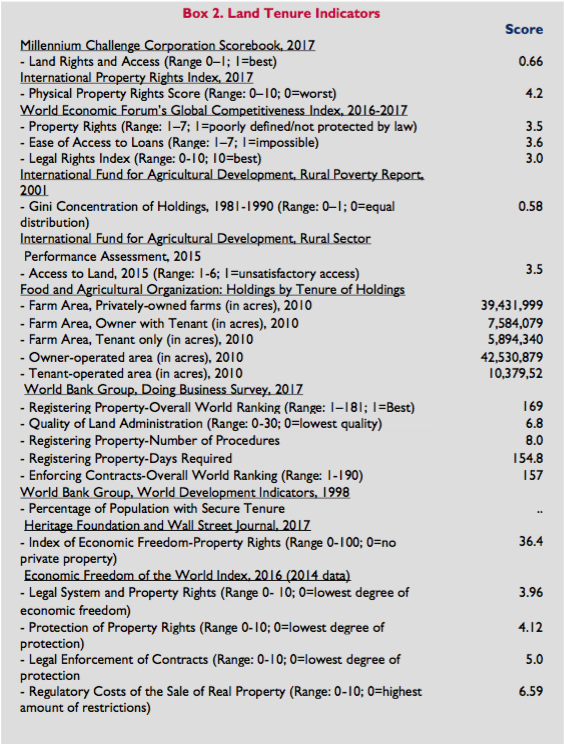

Ownership of irrigated land in the Indus Valley is highly concentrated. Between 50 percent of rural households are reported to be landless or near-landless. The landlord-tenant relationship based on patterns of unequal land distribution remains strong in Pakistan. Tenant farmers either lease or sharecrop land when they can or work as laborers on and off farms; many are raising stall-fed livestock. Poverty is highly correlated with landlessness and is seen as contributing to political and social instability. Repeated government attempts to address inequality of access to land and tenure insecurity have largely failed to transform the system. Tenants and sharecroppers have little incentive to invest in sustainable production practices. Insecure land tenure, coupled with poor water policy and management, has led to increasing degradation of land. Undervaluing the water supply has led to waterlogging and inefficient water use in some areas while poor water distribution has caused lack of water in other areas, lowering the profitability of land and the incentive to invest in complementary inputs.

Enactment of a comprehensive legal framework for establishing more equitable access to property and more transparent land administration could, many analysts believe, contribute to both political and economic development objectives. Given Pakistan’s history, however, the preparation and administration of such a framework would require substantial and sustained leadership on the part of both federal and provincial governments. Achieving commitment to drafting such land-reform legislation will require considerable political will. While it might be a challenge to create the right mix of political and economic incentives that will compel political and business elites to sponsor and pass legislation that privileges other socio-economic and class interests over their own, political leaders at the federal and provincial levels will need to work creatively and proactively to establish such incentives. Alternatively, linking statutory law with local customary law, ensuring that women have rights to property as established in law, and the establishment of a land registration system that incorporates the current tax revenue-based system of records with standardized documents and registries could increase tenure security and reduce land-based conflicts.

Reforms could also address urban land issues, currently cited by Pakistani firms as one of the barriers to investment. As government ownership of land in urban areas and informality in the urban land-tenure sector are significant, a more proactive role for local development authorities to address housing and industrial land is both necessary and appears feasible. There also seems to be a need for more effective governance of urban areas to allocate land for low-income housing and prevent illegal land seizures and squatting.

Cities and municipalities still must clarify and understand the balance of power between the federal and provincial government as they operationalize the 18th amendment to the Constitution, but weak and politicized municipal governments cannot maintain peace and security in ethnically and religiously diverse and densely populated areas.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

Drawing on experience elsewhere, donors could develop innovative options for increasing rural land access for the poor. Micro-plots, for example, could provide poor households with the economic, nutritional and psychological benefits of landownership without requiring the government to identify large amounts of agricultural land for redistribution. The development of methods for permitting women to acquire land and water rights in ways consistent with Islamic law and Pakistan’s Constitution could increase women’s economic opportunities and productivity.

Initiatives to address urban land issues could encompass housing for the poor as well as accessibility of space for commercial and industrial investments, including cultural heritage tourism. Increased attention to housing for the poor could improve public health and safety and, through increased security of tenure, encourage investment in and maintenance of properties including those in historic areas. The Orangi Pilot Project in Karachi provides a successful model for the development and distribution of services in squatter settlements. Donors’ support for removing barriers to urban investment by improving access to land (and services) could contribute to job creation and to the stability Pakistan needs.

Pakistan has no comprehensive water policy or water law defining rights to resources. The lack of a national water policy, and what that means for water management and distribution, has direct ties to and must be formulated within the context of 1960 Indus Water Treaty, which regulates much of the country’s water supply. The Government of Pakistan recognizes the need for a water resource strategy and formal, enforceable communal and individual property rights to water. The government has drafted numerous water policy statements and prepared several water resource strategies, but a policy and strategy have not yet been adopted. Moreover, Pakistan’s constitution assigns provincial governments the main responsibility for drinking water and sanitation service delivery, making national policies difficult to enforce. Donors could provide technical assistance and support to assist the government in creating the political will as well as assisting its current efforts to create a comprehensive legal framework governing water resources, develop a sequencing plan for adoption of necessary components and create an implementation program that responds to the challenges posed by the environment while taking advantage of successful local community governance models and water resource strategies.

Donors might continue to support the systematic upgrading of land, water and forest administration in urban areas as well as between the federal government and the provinces when other assistance and investments are being made. Over time, integration of resource governance responses with other kinds of assistance could lead to greater tenure security, broader access to land and water and sustainable use of forests. All of this could promote economic and social development and enhance political stability and inter-provincial harmony.

With growing global interest in carbon emission reductions and the Government of Pakistan embarking on its own Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) readiness, donors could provide technical assistance and support to assist the government in its efforts to create a comprehensive legal framework governing carbon rights and financial payments. Improving the ability of a range of institutions who historically have not been involved in development projects and programming, such as the Meteorological Department, is needed to ‘climate proof’ both the EIA process and infrastructure planning.

Private and communally-owned forests and woodlots provide the majority of the country’s wood and fuelwood requirements. Watershed and rangeland management are needed to enhance biodiversity, maintain fodder for livestock and reduce the costly impact of flooding. Donors could provide technical assistance to forestry departments at the federal and provincial levels in an effort to improve forest quality and develop a strategy of public-private partnerships for commercial timber production that would include strengthening business management skills and record keeping.

Pakistan has experienced heavy rains, flash floods, landslides and droughts since 2010. The recent establishment of provincial disaster management agencies provides donors with an opportunity to promote integrating disaster risk reduction measures within this new decentralized management structure. Given the multi-tiered nature of implementation at the federal and provincial level, horizontal and vertical integration driven by land use and management exercises coupled with community enumeration exercises would strengthen coordination and resilience in disaster risk reduction and post-disaster management. Legal and policy reform is needed, as current environmental laws do not fully include climate change, disaster risk reduction or climate mitigation or adaptation.

Rule of law in many densely-populated urban areas and in remote rural areas remains weak due to corruption and collusion. Donors could support police to disarm criminal gangs and land mafias. Capacity building and strengthening an internal check and balance system is needed to dismantle collusion between police and local bureaucrats. Resources are needed for a range of public institutions, including municipalities, to help officials reclaim their administrative functions. This, in turn, would improve the provisioning of goods and service and increase residents’ quality of life.

Summary

Land ownership is highly concentrated in rural Pakistan, and is a root cause of persistent poverty and instability countrywide. Only two percent of households have land holdings larger than 20 hectares, accounting for 30 percent of total land holdings (World Bank 2014). In urban areas, a lack of coordination between land-owning institutions, and weak local governance, continue to perpetuate power imbalances that not only enable violent extremism, but also exploitation of poor communities that reside in squatter settlements.

Land with access to water is the principal asset in the rural economy and poverty is strongly correlated to landlessness. While, the highest rate of landlessness is in the Sindh Province (PILDAT 2016b), about 50 percent of the rural population is landless or near-landless and lacks access to irrigation water, rights to surface and groundwater and other factors of production (Ghosh 2013).

Unequal access to land and inefficient and inequitable systems of water-management are creating patterns of natural resource use that diminish agricultural productivity, contribute to land degradation and perpetuate poverty and social instability. Furthermore, as bank loans for agriculture and other productive activities are tied to using land as collateral, a large percentage of women and landless farmers are unable to secure loans.

Unequal access to land and inefficient and inequitable systems of water-management are creating patterns of natural resource use that diminish agricultural productivity, contribute to land degradation and perpetuate poverty and social instability. Furthermore, as bank loans for agriculture and other productive activities are tied to using land as collateral, a large percentage of women and landless farmers are unable to secure loans.

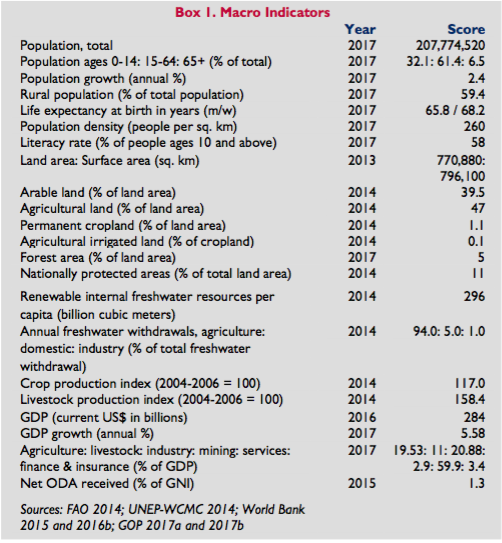

Only one-third of the population has access to safely-managed drinking water. Access to sanitation is much lower, with no safely managed sanitation in the country. Less than half of the rural population has access to basic sanitation. Shared latrines are common in urban areas, with an estimated 20 persons per toilet (Shaikh and Naib 2017).

The Land Reform Act of 1977—Pakistan’s third and most recent structural effort at addressing inequality of land access and land tenure since Independence—failed to meet its objectives. The legislation attempted to plug gaps in prior legislation and implement tenancy, land ceiling and land distribution reforms. Almost all of the minimal progress made occurred under the initial 1959 reforms. Pakistan’s uneven land distribution remains unaddressed. The country is also plagued by poorly functioning, inadequate and duplicative systems of land administration and an overburdened and ineffective formal court system. Parallel customary systems of transferring land and resolving land-disputes prove more accessible and efficient, creating a pluralistic legal environment.

Pakistan has a semi-arid climate and uses almost all available surface and groundwater resources to meet the demands of the agricultural, industrial and domestic sectors. Pakistan is considered the third most water-stressed country in the world (Shams 2017b). Ninety percent of the Pakistan’s water resources are used in agriculture, which is much higher than the global rate of seventy percent (Worldometers n.d.; Tanzeem 2017). Water scarcity is such that the country could face a critical water shortage by 2025. Recognition of an impending water crisis increases tensions not only between Pakistan and India, but also within the country, as provincial governments compete for scarce water resources (Shams 2017b). The Indus Basin Irrigation System (IBIS) is the largest contiguous irrigation system in the world (FAO 2011b). Only 60 percent of the water from the IBIS reaches farms and with loss of water during transmission, only 35-40 percent of canal water reaches the crop root zone (World Bank 2014). The demand for irrigation and drinking water is increasing. About 50 percent of water in irrigated systems comes from groundwater; the energy costs to pump the water are increasing; and aquifers are not being adequately recharged through the development of rainwater harvesting and storage. In urban areas, water supply is only available between four and sixteen hours per day (Shaikh and Nabi 2017).

The quality of agricultural and rangeland in Pakistan is degraded. The country has one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world and its forests cannot meet the population’s need for fuelwood.

Due to pressure of customary law and traditional practice, women in Pakistan have difficulty exercising the rights to land granted to them by constitutional, statutory and religious law. Women’s access to the natural resources they depend on for their livelihoods is inherently insecure and easily lost in times of scarcity.

Pakistan has significant mineral deposits, including gemstones, coal, copper and iron ore. Federal National Mineral Policy, and procedural laws and policies at the provincial level, regulate mining operations and investments.

In 2013, Pakistan witnessed its first democratic transition to power in 65 years with the completion of a full term of elected government (GOP 2014). The Government of Pakistan’s Vision 2025 aims to halve poverty by that year and raise the country to upper-middle income status by pursuing an export-led development strategy and doubling productivity with strong social values that promote peace, security, inclusiveness and inter-provincial harmony. Vision 2025 includes youth-centered programming and promotes increases in the quality of life through more efficient and effective water conservation and development, and investments in sewage treatment and sanitation. In order to increase economic growth, the vision includes energy and infrastructure development (GOP 2014; GOP 2015d).

Land

LAND USE

Pakistan has a total land area of 770,875 square kilometers. The total area does not include the disputed territories of Jammu and Kashmir (CIA 2017; 11,639 square kilometers and 72,520 square kilometers respectively), which are claimed by both Pakistan and India. Pakistan’s territory is divided into four provinces (Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa [KP], Punjab and Sindh) and four federally administered territories (Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), Gilgit-Baltistan and Islamabad Capital Territory or ICT). The Government of Pakistan does not recognize indigenous peoples, rather referring to them as tribal. The Federally Administered Tribal Areas, a semi-autonomous tribal area in northwest Pakistan, is divided into seven agencies and six Frontier Regions bordering on south-eastern Afghanistan (ICG 2015). The Provincially Administered Tribal Areas (PATA) are administrative subdivisions in the Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces that include areas such as Chitral and Swat (IFAD 2012; ICG 2015).

Pakistan is the second most urbanized country in South Asia (World Bank 2014). It has a population of 208 million people, and had an annual average population growth rate of 2.4 percent between 1998 and 2017. Population growth during that period was greatest in Islamabad, Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (GOP 2017b). Nearly 60 percent of the population lives in rural areas. Even though the average per capita income is $1,512 (IFAD 2016b), there is significant income inequality. The bottom 40 percent of Pakistan’s population lives on less than $2.27 a day (World Bank 2016a) and 53 percent live on less than $1.90 per day (UNDP 2016e). Nearly 30 percent of the population lives below the poverty line (UNDP 2016b). In 2013-2014, 29.5 percent of the population was estimated to live in poverty (Jamal 2017).

Ninety-seven percent of the population is Muslim. Pakistan’s population is made up of six principal ethnic groups: Punjabi 45 percent, Pashtun (Pathan) 15 percent, Sindhi 14 percent, Sariaki 8 percent, Muhajirs 8 percent, Balochi 4 percent and other 6 percent (IFAD 2012; CIA 2017). The Pashtun are the principal inhabitants of Pakistan’s Tribal Areas, which are the poorest regions on the country. Most residents of the Tribal Areas are dependent on livestock-rearing and subsistence farming for their livelihoods (GOP 2006a; Mongabay 2010; World Bank 2015).

Pakistan’s landscape ranges from the Himalayan and Hindu Kush mountains (including the world’s second-highest peak, K2), intermountain valleys, the irrigated plains of Punjab and Sindh provinces, the dry western plateaus of Balochistan Province and the sandy desert in eastern Sindh and Punjab provinces (UNEP 2014).

About 40 percent of Pakistan’s total land area is arable land, approximately 90 percent of which is located in the Indus River Plain of Punjab and Sindh provinces (FAO 2011c). Seventy-six percent of agriculture land is irrigated (PARC n.d.). The balance of cropland is used for non-irrigated cropping, including about 5 million hectares of rainfed (barani) agricultural land in norther Punjab and southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) provinces and seasonal floodplains in the Indus Delta. Pakistan’s main crops are wheat, maize, rice, sugarcane and cotton (World Bank 2009; PARC n.d.; GOP 2017b). Wheat, rice and sugarcane are all high intensity water use crops that contribute to water scarcity in the agriculture sector (Tanzeem 2017).

About 40 percent of Pakistan’s total land area is arable land, approximately 90 percent of which is located in the Indus River Plain of Punjab and Sindh provinces (FAO 2011c). Seventy-six percent of agriculture land is irrigated (PARC n.d.). The balance of cropland is used for non-irrigated cropping, including about 5 million hectares of rainfed (barani) agricultural land in norther Punjab and southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) provinces and seasonal floodplains in the Indus Delta. Pakistan’s main crops are wheat, maize, rice, sugarcane and cotton (World Bank 2009; PARC n.d.; GOP 2017b). Wheat, rice and sugarcane are all high intensity water use crops that contribute to water scarcity in the agriculture sector (Tanzeem 2017).

About 65 percent of Pakistan’s total land consists of desert, mountains and urban areas. These areas include about 52.3 million hectares of rangeland (Ahmed 2016) and 35,872 square kilometers of urban land (World Bank 2016b). Balochistan covers 42 percent of the country, and 93 percent of its land area is classified as rangeland (PARC n.d.; GOP 2017b). Pakistan has an estimated livestock population of about 232 million cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, camels and other animals (GOP 2017b). Livestock production (primarily cattle and buffalo) is integrated with crop production; animals are reared in intensively cultivated irrigated plains and stall-fed crop residue and forages. Sheep, goats, subsistence cattle and camels are most often kept on rangeland and are tended by nomadic and semi-nomadic groups. Pakistan’s leading livestock industry is dairy, placing it among the top ten milk-producing countries in the world (FAO 2015b). The country’s annual milk production is estimated at 55 million tons (GOP 2017b). Given population growth in urban areas, the demand for high-value perishable products such as dairy is growing, with increasing government investment to increase rural dairy production through infrastructure improvements and joint ventures. In December 2016, one of the largest foreign private direct investments in the dairy sector took place when Royal Friesland Company acquired 51 percent of Engro Food Pakistan for $450 million (PARC n.d.; GOP 2017b).

Forests cover approximately 5 percent of the country’s total land area (GOP 2017b). Most coniferous forests are located in KP province and the Northern Areas. Mangrove forests are found in the Indus Delta and along the coastline of the Arabian Sea. Nationally protected areas cover 11 percent of total land area, and the annual rate of deforestation is estimated between 1.66 to 2.24 percent (UNEP-WCMC 2014; Nazir and Olabisi 2015). Forestry accounts for nearly 15 percent of the country’s GDP (GOP 2017b).

In barani (rainfed) areas, the overall productivity of land and livestock is lower than in irrigated areas, and residents rely more heavily on access to forests and rangeland. In these areas landholdings tend to be dominated by owner-cultivators, and livestock is more important to agricultural production than in irrigated areas (Shah and Husain 1998; ADB 2009).

Pakistan’s agricultural land suffers from heavy soil erosion and steady degradation. Deforestation, livestock grazing and improper land cultivation techniques have caused reservoirs to silt up, reducing the capacity to generate power as well as the availability of water for irrigation. Countrywide, livestock populations exceed the rangeland’s carrying capacity, destroy natural vegetation, overwhelm water sources and cause soil erosion. At least 25 percent of the country’s irrigated land suffers from various levels of salinity, with 1.4 million hectares rendered uncultivable. The coastal strips and mangrove areas are stressed by reduced freshwater flow, sewage and industrial pollution (GOP 2002; World Bank 2006).

Pakistan’s total GDP in 2016 was an estimated $284 billion (World Bank 2016b), with 59 percent attributed to services, 20 percent to industry and 21 percent to agriculture. Livestock accounts for nearly 60 percent of agricultural GDP and contributes just over 11 percent of the country’s GDP (GOP 2017b). Much of Pakistan’s industry (e.g., textiles, sugar) is also linked with agricultural production (World Bank 2009; World Bank 2007a; UNDP 2009). While approximately 45 percent of the population works in agriculture, rural transformation is accelerating with more than 50 percent of rural workers employed away from farms (IFAD 2016a). Structural transformation within the national economy and annual poverty reduction are slow partially due to the fact that annual growth of agricultural labor productivity is less than 1 percent per year (IFAD 2016a). Pakistan is also among the world’s 20 leading producers of cement (Renaud 2015).

In 2013, the GermanWatch Climate Index ranked Pakistan as the eighth most-affected country by climate change between 1991-2010 due to flooding, drought and other climatic events. Maplecroft ranked the country as the 16th most vulnerable to climate change impacts over the next 30 years (cited in Fisher 2014). The main reasons for the country’s vulnerability include but are not limited to: population growth, ecosystem degradation, lack of land tenure and low institutional capacities. Climate change poses a serious food and water security risk to the country due to the importance of subsistence and rain-fed agriculture in rural economies (Fischer 2014).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Land ownership in rural Pakistan is highly concentrated. Land, especially irrigated land, is the rural economy’s principal asset. Poverty is strongly correlated with landlessness. The Government of Pakistan conducts an agricultural census every ten years. In 2010, smallholders with less than five acres of land made up 67 percent of privately-owned farms. Countrywide, six percent of privately-owned farms were over 25 acres. The average size of operational farm holdings in the country was 6.4 acres (Zaidi 2015).

Pakistan has engaged in three land-reform efforts (1959, 1972 and 1977) under three different governments. According to the Federal Land Commission, the government has, to date, expropriated 1.8 million hectares (less than 8 percent of cultivated area) and redistributed 1.4 million hectares to 288,000 beneficiaries. About two-thirds of land expropriation and three-fourths of the land distribution were accomplished under the initial 1959 land reforms (Khan 2000). Average farm sizes have decreased with land reform from just over 5 hectares in 1971 to just over 3 hectares in 2000 (IFAD 2011).

Land distribution continues to be highly skewed. The Land Reform Act of 1977—Pakistan’s third and most recent effort at addressing inequality of land access and land-tenure insecurity since Independence—failed to meet its objectives of plugging gaps in prior legislation and implementing tenancy, land ceiling and land distribution reforms. The 1977 Act was followed by the imposition of martial law and much of the momentum fueling reforms dissipated. In the years that followed, the courts ruled various provisions of the Act un-Islamic and political will to address land issues waned. A resurgence of interest in land reform and attendant revisions to the Act (mostly to pave the way for expansion of commercial farming interests) took place in the 1980s but without addressing the large numbers of landless people. Occasional uprisings occur. In March 2010, landless peasants marched toward Lahore to demand land and, in April 2010, the Punjab government announced a program to provide 255,024 plots to landless peasants (Khan 1981; Khan 2000; Critical PPP 2010; Nation 2010). The percentage of farm area that is under tenant farming decreased from 21.6 percent in 1980 to 11.1 percent in 2010 (Ziadi 2015). It is unclear if the land that has been taken out of tenant farming has been redistributed to peasants and now categorized as privately-owned farm land or if it has been consolidated into larger farms. The average size of larger operational land holdings (over 150 acres) increased between the 1990 and 2010 from 312 acres to 435 acres (GOP 2010; Zaidi 2015).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973 (as amended and restored) provides that Islam is the state religion and that all laws must be in alignment with the Qur’an. The Constitution provides that every citizen shall have the right to acquire, hold and dispose of property, subject to reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the public interest (GOP Constitution 1973; Reynolds and Flores 2009).

The 18th amendment to the Constitution passed in 2010 represents the decentralization of fiscal, administrative and political power from the federal to the provincial level (Fischer 2014, GOP 2014). A total of 17 ministries devolved power in 2010-2011 including: environment, food and agriculture, livestock and dairy, local government and rural development, education and health (Resnick and Rana 2016). Provinces are adapting federal regulations to meet their needs and development goals at different rates. While the Punjab adopted the 1997 Pakistan Environmental Protection Act or “Federal Act” with a limited number of changes in 2012, the Government of Balochistan in 2013 made significant changes to the Federal Act, in some cases making provincial environmental policies stronger than federal mandates. In 2014, Sindh and KP passed their own Environmental Protection Acts (Fischer 2014).

Much of Pakistan’s civil law, which is retained from colonial legislation originating in India, has been adapted over the years to reflect the Islamic character of the country (97 percent of the population is Muslim). The structure of Pakistan’s legislation is fluid and in a near-constant state of amendment as it continues to conform and adjust to Islamic jurisprudence, which is itself evolving (GOP Constitution 1973; Reynolds and Flores 2009).

Statutory law specific to land rights in Pakistan is dated, fragmented and incomplete. More than two dozen laws govern a variety of land matters at the national and provincial levels. There are numerous laws that regulate ownership, transfer, acquisition and tenancy. Land laws in rural and urban areas are often different (UN Habitat 2012b). Provincial revenue legislation provides for landholding categories, recordkeeping, land transactions, surveys, partition and authority of revenue department officials. Property rights of the tribal population of FATA and PATA are subject to a separate legal framework, the majority of which consists of customary law (GOP Constitution 1973; Khan 1981; USAID 2008, UN Habitat 2012b; United Kingdom 2017).

Pakistan has a well-developed and highly diverse body of customary law governing land rights. Customary law differs among provinces and geographical subdivisions, tribes, classes and residential status, and is enforced by established tribunals known as jirgas. Customary law governing land issues ranges from marital property rights to principles governing boundaries. Particularly in the Tribal Areas, people regulate their own affairs in accordance with customary law and the government functions through local tribal intermediaries. Tribes recognize individual land ownership, ownership by a joint or extended family and collective landownership by a tribe (Shirkat Gah 1996; GOP 2006a).

TENURE TYPES

Land in Pakistan is classified as state land, privately held land or land subject to communal rights or village common land under customary law. Land for which there is no rightful owner vests in the provincial government if within a province, or with the federal government if not (GOP Constitution 1973; GOP 2006a; USAID 2008; UN Habitat 2012b).

Major tenure types in agricultural systems are summarized as follows.

Ownership. Ownership is the most common tenure type in Pakistan. Private individuals and entities can obtain freehold rights to land, and communal ownership rights are recognized under customary law (Anwar et al. 2005; World Bank 2007a; GOP 2006a).

Lease. Formal term leases are common for parcels of agricultural land that exceed 30 hectares. Leases are for fixed rates, generally run at least a year and may have multi-year terms. Tenant farmers also may have informal and unwritten lease arrangements for much smaller plots from landlords. In 2010, approximately 26 percent of tenant farmers held leases (GOP 2010). Leases may be written or oral agreements (Anwar et al. 2005; FAO 2011c).

Sharecropping. Sharecropping arrangements locally known as battai are common on small- and medium-sized parcels of agricultural land (less than 30 hectares). Roughly 71 percent of Pakistan’s tenant-operated land was sharecropped in 2010, and 84 percent of sharecropper households are vulnerable to living in poverty (GOP 2010; Jamal 2017). Sharecropping arrangements are often intergenerational, as over time landlords form close bonds with tenants and their families (Khan et al. 2017). Sharecropping arrangements usually provide the landowner with half the production from the land; arrangements vary regarding provision of inputs. Middlemen known to both landlords and tenants may broker sharecropping agreements. Most agreements are unwritten (Anwar et al. 2005; Khan et al. 2017).

SECURING LANDED PROPERTY RIGHTS

Freehold land in Pakistan tends to be retained by families and passed inter-generationally by inheritance. Ownership is rarely registered. Despite formal laws mandating registration, incentives for registering land are weak or nonexistent and procedures complicated and lengthy. Land is typically titled in the name of the head of household or eldest male family member of an extended family. While community property rights are recognized in formal law, joint titling of land is uncommon. Islamic law is often inconsistent with statutory law; Islamic law permits oral, unrecorded declarations of gifts of land, while statutory law requires a writ, with the Benami Act legalizing documented but unrecorded transactions. Land in FATA is not recorded. The amount of land actually registered countrywide currently is unreported, but will be known once digitization across all provinces and territories is complete (Dowall and Ellis 2007; GOP 2006a; SDPI 2008a).

Landowners who cannot or do not want to cultivate agricultural land routinely lease it out under fixed-term agreements or sharecropper arrangements, and the land-lease market is quite active. Leasehold interests tend to be considered secure within the circumscribed terms agreed to by the parties. There are two types of tenancy: occupancy tenants who have statutory rights to occupy land; and simple tenants who occupy land on the basis of a contract with a landlord (Bisht 2011). In rural areas, tenants on smallholdings have seasonal or annual contracts that as a matter of practice are generally renewed for a number of years. The social hierarchy and consequential power relationships between landed families and tenure-insecure tenants however, creates dependency and keeps tenants in subordinate social and political positions. Tenancy reforms have been ineffective in increasing security and tenants have little legal recourse in the event of eviction (Jacoby and Mansuri 2006).

In urban areas, those with economic means can purchase houses and house plots; those with limited means usually rent shelter in informal settlements or encroach on surrounding land (Dowall and Ellis 2007; Jacoby and Mansuri 2006; Sayeed et al. 2016).

Foreign-controlled companies that are incorporated in Pakistan can own land in Pakistan. Foreign individuals must obtain permission from the Home Department before acquiring land in Pakistan (Martindale-Hubbell 2008).

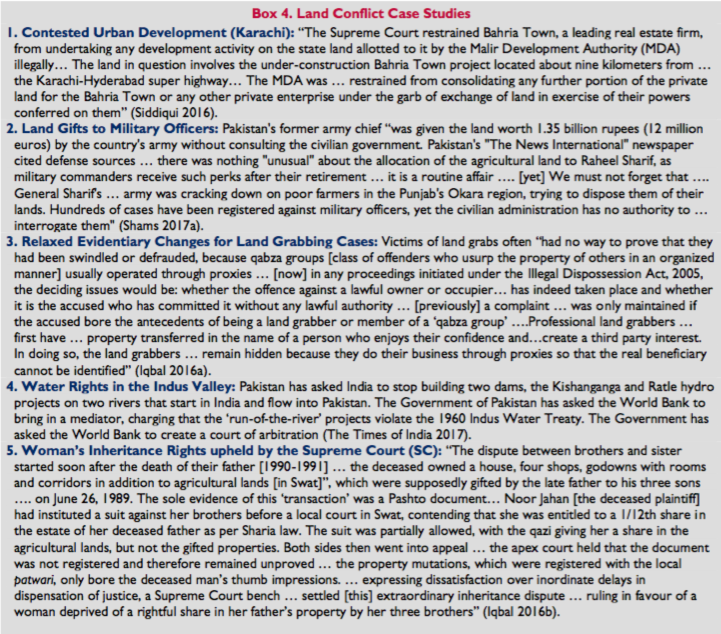

Squatting and land-grabbing are common in Pakistan. The lack of land available for housing development and lease by individuals in growing urban areas has forced migrants into informal settlements and squatting on vacant land. Pakistan is also home to individuals and groups known as the Land Mafia who illegally take possession of land or claim ownership of land and dispossess true owners through legal or extra-legal means. The Illegal Dispossession Act of 2005 was passed in an effort to address the problem, and its execution has been improved with new evidentiary protocols passed in 2016 (see Box 4).

In provinces adopting the national Transfer of Property Act, 1882, the Registration Act, 1908 and the Stamp Act, 1899, all documents transferring interests in land (including leases and conveyances) must be registered with the Provincial Land Registrar, the Provincial Board of Revenue or certain private housing and development authorities—parallel systems that have overlapping authority and do not coordinate information. Provinces that have not adopted the central legislation can adopt their own registration requirements, and in any province local authorities can adopt regulations that are contrary to the requirements of the central legislation. Urban land granted to the Army or housing development authorities is registered under separate systems maintained by those bodies, with no record maintained by the Provincial Registrar or revenue department (USAID 2008).

The Government of Pakistan, with assistance from donors, has started to improve land tenure security through the introduction of the digitization of land records. Improvements though are needed to create a comprehensive legal framework governing land rights and processes across the provinces and territories to address administrative inefficiencies and ineffectiveness within formal dispute-resolution systems. Finally, strong and multiple customary laws create insecurity of land tenure for owners, women and potential purchasers, particularly in Balochistan and FATA (Jacoby and Mansuri 2006; Malik 2013; ICG 2015).

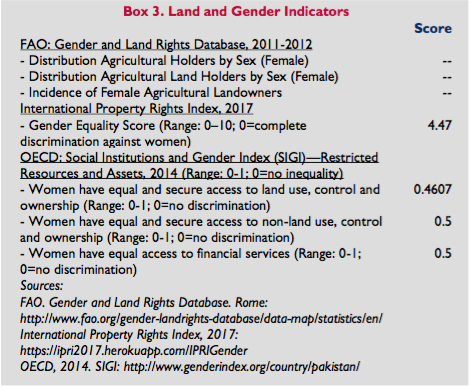

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Women in Pakistan have a legal right to own land under statutory, religious and customary law. While women comprise 72.7 percent of the agricultural labor force (UNDP 2016c), more men than women own land. Only 4 percent of women own land (either alone or jointly) compared to 31 percent of men (UNDP 2016d). Women are active in land rights movements and are advocating for jointly-titled land rights through their involvement in the Thappa Force (Yusuf 2016; Bano and Ghaffar 2014). With respect to women’s land rights and gender equality more generally, Pakistan has a Gender Inequality Index value of 0.567 ranking it 123 out of 148 countries (GOP 2015c). Pakistan’s ranking on the Human Development Index is also low – 148 out of 188 – due to low education and literacy rates, high infant and maternal mortality rates and a low number of women serving in Parliament. Strong patriarchal norms inhibit women’s ability to own and manage land and property. Many women do not inherit land which is a constitutionally protected right and are often threatened with violence if they do not waive their rights to land and property. Women in landed families might be more likely to inherit land, as a way to avoid land redistribution policy (Gul Khatak, Brohi and Anwar 2010). Nevertheless, women have a legal right to land after their father’s death through internal partitioning called khangi taqseem or family division. However, even when women possess such legal ownership, men deny their ability to access and control that land (Ali 2015). Further complicating women’s ability to exercise their land rights and increasing conflict within the family is inadequate parcel demarcation which comes to a fore when a woman (as a sister) tries to cultivate or build a house. Such confusion could be reduced if plot demarcation was required to take place at the time that partitioning takes place and name transfers are recorded in the revenue record. A limited number of inheritance violation cases make it to the Supreme Court (see Box 4).

Women in Pakistan have a legal right to own land under statutory, religious and customary law. While women comprise 72.7 percent of the agricultural labor force (UNDP 2016c), more men than women own land. Only 4 percent of women own land (either alone or jointly) compared to 31 percent of men (UNDP 2016d). Women are active in land rights movements and are advocating for jointly-titled land rights through their involvement in the Thappa Force (Yusuf 2016; Bano and Ghaffar 2014). With respect to women’s land rights and gender equality more generally, Pakistan has a Gender Inequality Index value of 0.567 ranking it 123 out of 148 countries (GOP 2015c). Pakistan’s ranking on the Human Development Index is also low – 148 out of 188 – due to low education and literacy rates, high infant and maternal mortality rates and a low number of women serving in Parliament. Strong patriarchal norms inhibit women’s ability to own and manage land and property. Many women do not inherit land which is a constitutionally protected right and are often threatened with violence if they do not waive their rights to land and property. Women in landed families might be more likely to inherit land, as a way to avoid land redistribution policy (Gul Khatak, Brohi and Anwar 2010). Nevertheless, women have a legal right to land after their father’s death through internal partitioning called khangi taqseem or family division. However, even when women possess such legal ownership, men deny their ability to access and control that land (Ali 2015). Further complicating women’s ability to exercise their land rights and increasing conflict within the family is inadequate parcel demarcation which comes to a fore when a woman (as a sister) tries to cultivate or build a house. Such confusion could be reduced if plot demarcation was required to take place at the time that partitioning takes place and name transfers are recorded in the revenue record. A limited number of inheritance violation cases make it to the Supreme Court (see Box 4).

There is momentum for gender equality at the Federal level. In 2011, Parliament passed The Prevention of Anti-Women Practices [Criminal Law Amendment] Act. The Act not only has strong prohibitions against child and forced marriage thereby criminalizing them, but also prohibits depriving women from inheriting any movable or immovable property at the time of succession. Forced marriage includes marriage for purposes of land, for settlement of personal disputes or disputes between two tribes [often referred to locally as “swap marriage” (Ahmad et al. 2016)] and marriage to the Holy Quran. Marriage to the Holy Quran is a common way for families to keep a female’s land inheritance within the family. Land cannot be lost as she cannot be married to an outsider.

Punishment for forced marriage to the Holy Quran includes imprisonment for whoever compels, facilitates or arranges it (quite often a brother or father). The punishment may extend to seven years, shall not be less than three years and shall be liable to a fine of 500,000 rupees (Noreen and Musarrat 2013; Zaman 2014). Punishment for depriving a woman of her inheritance includes a prison term which may extend to ten years but not be less than five years, or a fine of one million rupees, or both (Zia Lari 2011). Such crimes against women continue due to a lack of law enforcement, a lack of political will, a weak criminal justice system and lack of public pressure (Munshey 2015).

Nevertheless, Pakistan is a patriarchal society with an uneven practice of patriarchal social norms across the country and depending on area of residence (urban/rural). In urban areas, professional women are increasingly purchasing house plots in their own names, but women’s ownership of land in rural areas continues to be rare in most regions, despite provisions in customary and Islamic law that expressly provide such rights. Men continue to dominate in social, economic and political spheres particularly in tribal areas in FATA, PATA and in parts of Balochistan and Sindh. Men are presumed to control land and other family assets (Mehdi 2002; SDPI 2008b; USAID 2008; Gul Khatak, Brohi and Anwar 2010; Malik 2013; ICG 2015).

Customary law differs among provinces and geographical subdivisions, classes and tribes, creating differential impacts for women. For example, land ownership for women in the Jamaldini and Badini tribes of the Noshki District in Balochistan is nearly non-existent as these tribes practice ‘mard bakhsh’ (literally: willed to a man), meaning that only men with sons may own land (Gul Khatak, Brohi and Anwar 2010). Women’s access to land and property is particularly dire in FATA and PATA. Violent extremists operating in these regions have an overt agenda of gender repression. Discriminatory legislation that has been overturned at the federal level still operates in these areas. For example, the enforced Hudood Ordinances (1979) do not accept the testimony of women and the FATA Frontier Crimes Regulations (FCR 1901) suspends constitutionally guaranteed rights for gender equality and pro-women legislation. Women and girls are still considered property and are given away to settle disputes even though this act called swara was criminalized in 2006 by the Protection of Women Law (Malik 2013; ICG 2015). Similarly, these provinces do not follow Parliament’s lead regarding the 2011 Prevention of Anti-Women Practices Act that bars depriving women of their inheritance and a range of forced marriage practices (Zia Lari 2011; ICG 2015).

Neither customary nor Islamic law in Pakistan recognizes community property rights, but various provisions are made for the support of women, including agreements regarding payments and repayments of dowry, dower, haq mehr and maintenance. In some regions, dower paid by the groom’s family is substantial and often takes the form of land or a house that the husband’s family is expected to construct and put in the bride’s name. However, the impact on the bride is usually minimal because she will seldom exercise any control over the property in her name (Shirkat Gah 1996; World Bank 2005a).

Customary law grants widows use-rights to land until they remarry or their children come of age. Islamic law divides the deceased’s property into 12 shares and grants widows a one-quarter share of her husband’s property if she had no children or one-eighth of his property if she did (Hasan 2011). Daughters may inherit land rights (half the share of a son), depending on the practice within the family. If daughters receive land, they often relinquish the land to their brothers or other male relatives, following the religious practice known as tanazul (relinquishment). If a woman receives land rights through inheritance, her rights will likely be challenged by male relatives even if the bequest is supported by her parents and even if the gift was consistent with Islamic law (Ali 2015). Furthermore, women often do not challenge male relatives who usurp their land rights as they do not wish to upset their parents or lose the love and support of other family relatives (Ahmad et al. 2016) or because women themselves believe that they received dowry instead of land (Gul Khatak, Brohi and Anwar 2010).

There has been little acceptance under customary and religious law for women’s ability to control and manage land. Under customary law the senior male of the family holds the family land in his name (Shirkat Gah 1996; Mehdi 2002; SDPI 2008a; SDPI 2008b; Mumtaz and Noshirwani 2008; World Bank 2005a; Gul Khatak, Brohi and Anwar 2010). Following the passing of the 18th amendment to the Constitution, important legal steps are being made at the provincial level to promote gender equality in land ownership. The Government of Punjab passed both the Punjab Partition of Immovable Property (Amendment) Act, 2015, and the Punjab Land Revenue (Amendment) Act, 2015, to ensure property and inheritance rights for women living in the province (PILDAT 2016a).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Pakistan’s poorly functioning, inadequate and duplicative system of land administration has been improved with government and donor investments in digitizing land records. In June 2012, the Supreme Court of Pakistan directed all provinces to computerize land records. The Government of Punjab Province has completed the digitization process with the other three provinces in various stages of the process. Digitization is underway in KPK and in May 2017, the Government of Balochistan announced its intention to digitize land and revenue records (Zafar 2017). Once computerization of land records is complete, Provincial Revenue Boards stand to increase revenue via fees from crop inspection, tenancy, identification of tillers and other services that integration of the land system with Agriculture Department will enable. Digitization also improves transparency in record keeping and increases efficiency in revenue assessment. Automated, computerized systems promote secure and reliable transactions, real time updating of record and provision of reliable data to resolve land disputes. It will also help ease access to land revenue records by all stakeholders, maintaining efficient record for ownership title and data mining for taxation plans. Improving land administration and land governance contributes to at least four out of eight pillars of Pakistan’s Vision 2025, namely: empowering women, inclusive growth, modernization of the public sector and food security. Vision 2025 highlights land governance as a key factor for an enabling environment for the private sector and urban development (GOP 2014).

The formal court system remains overburdened and ineffective. Parallel customary systems of transferring land and resolving land disputes prove more accessible and efficient, creating a pluralistic legal environment (Dowall and Ellis 2007; USAID 2008; Ali and Nasir 2010).

In other provinces and territories, the number of institutions with responsibility over land registration continues to enable an environment ripe for rent-seeking by officials, local patwaris (the lowest level revenue officer who collects and keeps land records) and others involved in the land registration process. In some areas, women report difficulties dealing with patwaris who were reluctant to deal with women or to record women as land owners (Ali and Nasir 2010; USAID 2008) or women do not approach a male patwari for cultural reasons (Pott 2017).

The Provincial Land Registrar and Provincial Board of Revenue have responsibility to maintain registries of landholdings and revenue payments, but the records are not comprehensive. Until digitization is complete, junior revenue officers known as patwaris survey land, perform boundary demarcation and, in many jurisdictions, register land ownership, land transactions and mutations of records, and manage land distribution. The patwari has custody of the original land records (17 separate registers) for rural and urban land in a given area. Records of land owned by the military and granted to housing and development authorities are maintained by those separate institutions, and the registrations are not lodged with the registrar or revenue departments. In some cases, provincial revenue departments bypass the land registrar.

Land record digitization changes the role of the patwari over land at the village level with respect to registration and record keeping. Following digitization a registered land owner, for a small fee, can obtain a certificated duplicate of land records from the local land record service center and keep such records at home. Land record service centers have separate seating areas for women and women’s counters specially to provide land records services to women (Pott 2017). The patwari, however, still has a role to play in land-related dispute resolution at the local level.

The number of institutions with responsibility over land registration has created an environment ripe for rent-seeking by officials and others involved in the land registration process (Ali and Nasir 2010; USAID 2008). Registering a land transaction in Pakistan involves an average of 7.7 procedures. Registration steps are not standardized across the country, for example, there are seven procedures in Lahore and eight procedures in Karachi. Overall, land registration requires an average of 154.8 days and costs 4.6 percent of the total property value (World Bank 2017b). Registering property has been made more expensive by the recent doubling the capital value tax to 4 percent (World Bank 2017b). In an urban area such as Karachi, the formal land-registration process in the context of a sale begins by obtaining a ‘no objection’ certificate from the District Revenue Officer at the town or city level. The ‘no objection’ certificate written in favor of the seller permits the sale of a property. To make sure that there are no other claimants or interests in the property to be sold, public notice of the transaction must be published in two widely-circulating newspapers in both English and Urdu inviting objection to the sale. During the seven-day objection period, the buyer will verify the authenticity of the documents provided by the seller followed by a title search conducted at the sub-registrar’s office. A lawyer or deed writer is engaged to draft the sale purchase agreement. Thereafter, the buyer pays stamp tax, capital value tax, town tax and registration fee either to the Government Treasury or the National Bank of Pakistan. The receipt of payment for the property is brought to the Stamp Office for the issuance of the stamp paper which registers the value of the sale (money deposited) on the deed. The stamp paper is presented to the Registrar who records the change of ownership. The execution of the new deed is done before the Sub-Registrar of Conveyance/Assurance, with the name of the buyer recorded on the new deed. The last step, mutation or transfer of ownership, takes place after registration and includes obtaining a new title document (World Bank 2017b).

Despite reform, titling remains out of reach for the poor as even when squatter settlements known as katchi abadis (KA) have been regularized, only about one-third of regularized KA households obtain title deeds (Sayeed et al. 2016).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Rural land in Pakistan is rarely bought and sold. Land leases are more common and the lease market is active. Thirty-three percent of cultivated land was under some form of tenancy arrangement in 2000; in 2001–2002, 18 percent was sharecropped (the percentage sharecropped in 2010 is estimated to be about 66 percent). The productivity of sharecropped land is about 20 percent lower than that of owner-operated land (World Bank 2007a; Jacoby and Mansuri 2006; Barnhart 2010). In tribal areas, land transactions are verbal (Sabir et al. 2017). Land fragmentation is increasingly becoming a barrier to investment in small-scale production and underutilization of agricultural land. The compulsory requirement to divide land within the family following a father’s death is one reason for land fragmentation.

All of Pakistan’s cities are experiencing high rates of urban growth, due to an average annual population growth rate of 2.4 percent (GOP 2017a). Land and housing are scarce, housing is often of low quality (Shaikh and Nabi 2017) and prices are escalating. The state owns a substantial amount of urban land and is criticized by the business community for failing to develop the land or place it on the market. A survey of 700 firms in Pakistan identified land-market issues as the most significant barrier to investment; the business community contends that the government creates artificial shortages through inaction or occasional bans on the sale or transfer of state land.

Populations living in informal housing and KAs have increased (Dowall and Ellis 2007; USAID 2008; World Bank 2007a; Sayeed et al. 2016). Regularization of KAs has started to take place, especially in Karachi where an estimated 55 percent of the population resided in them in 2012 (Sayeed et al. 2016).

Pakistan recognizes simple mortgages, mortgages by conditional sale and usufructuary mortgages. Mortgage law was developed with attention to protecting farmers against moneylenders, and procedures for recovering the investment in the event of default are lengthy and costly for lenders. Pakistan has the lowest rates in the world for commercial bank lending for all types of mortgages at 0.2 percent of GDP (Sayeed et al. 2016). While ambiguous property rights have limited the availability of mortgages to wealthy individuals purchasing land in large urban areas (Martindale-Hubbell 2008; Dowall and Ellis 2007), alliances between provincial-level ruling parties, financiers and real estate developers have expanded the markets for upper-middle class housing, residential schemes and shopping malls at the expense of affordable housing for the poor (Sayeed et al. 2016).

Local land markets are highly inefficient (World Bank 2014). Constraints to the development of a more effective land market include high transaction costs, inaccurate land records, lack of efficient dispute-resolution procedures, high land prices in relation to income (especially agricultural income) and lack of credit. In urban areas, public land ownership is high and local development authorities together with political elites guide housing development (World Bank 2007a; Dowall and Ellis 2007; ICG 2017).

There are two categories of land available for foreign investment: state farmland and uncultivated land. The Government started promoting corporate farming with the passing of the Corporate Farming Ordinance in 2001 that allowed 99 leases held by foreign companies to be extended by 49 years and with no upper ceiling on land leases, and includes a number of tax holidays (FAO 2011c; Settle 2013; Ali 2015). In 2009, the government introduced an agricultural investment policy package and one million acres of land to attract international agricultural investors. The Board of Investment (BOI) advertised state farmland in Punjab and Sindh and hundreds of thousands of acres of uncultivated land in Balochistan and the Thar desert region of Punjab and Sindh. Investor inquiries were primarily of Middle Eastern origin (Settle 2013; Ali 2015). Agriculture also is a primary target for the Government’s Investment Promotion Strategy, 2010-2015 (FAO 2011c).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The 1973 Constitution and the 1894 Land Acquisition Act (including federal and provincial amendments) provide that the state can acquire property for a public purpose upon payment of compensation required by law. Specific circumstances in which the state can acquire property include: when necessary to prevent danger to life, property or public health; when the property belongs to an enemy or evacuee; when necessary for the proper management of the property; and to provide housing and services such as roads, water supply and power (GOP Constitution 1973).

The Land Acquisition Act requires public notification of an acquisition, an assessment of impacts and the valuation of affected assets by the District Land Acquisition Collector. Thereafter, the Act stipulates that the state will pay compensation in cash at market rates for land and crops to titled landowners and tenants who are registered with the Land Revenue Department or who possess formal lease agreements. Land valuation is usually based on recent 3- to 5-year averages of registered land sales rates, with an added 15 percent compulsory land acquisition surcharge. Local governments and donors implementing programs have considered the Land Acquisition Act to be too narrow and its safeguards inadequate to protect populations affected by land acquisitions. Compensation of land-based assets in cultural heritage sites, for example, is difficult.

In 2002, a National Resettlement Policy and Resettlement Ordinance were drafted. The draft policy and ordinance legislation expanded the categories of people entitled to compensation to include unregistered tenants, occupants and users of land, employees and businesses. The drafts also allowed for compensation in the form of land. The government has not adopted the draft policy and ordinance, but their terms guide some resettlement projects (ADB 2007).

Finally, a culture of environmental impact assessment (EIA) and a strategic environmental assessment (SEA) exists in Pakistan following the passing of the Pakistan Environmental Protection Ordinance, 1983.

This Ordinance made the EIA a requirement for any proposed project with possible adverse impacts on the environment and was made mandatory from July 1, 1994 (Fischer 2014). The EIA process has implications for sustainable development and resettlement for communities affected by infrastructure and other economic development projects. The public participation component of the EIA process is weak, used primarily to disseminate project-related information rather than to provide an opportunity for the public to ask about how a project might affect them and with consultation normally taking place after project construction has started. However, stakeholder concerns during the consultation process for the Sundar Industrial Estate Project resulted in a rejection of the project, as villagers whose land was compulsorily acquired for the project were not involved in the original EIA consultation. There is an on-going effort to integrate the effects of climate change into EIA procedures. The SEA process began in the early 1990s and continues to be used in the context of transport, large-scale irrigation and industrial development. The SEA process has been used to mainstream environmental sustainability into Pakistani policy (Fischer 2014).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Land conflicts are prevalent in rural and urban areas throughout Pakistan. There are three major causes for large-scale conflict in Pakistan with antecedents in British colonial rule. First, the British frequently gifted land to officers, bureaucrats and members of the judiciary and drew on the Land Colonization Act of 1904 to allot 10 percent of newly available irrigated agricultural land to the military rather than making such land available to local farmers (Settle 2013). Second, in order to protect British colonial interests from external forces, the colonial government did not develop transportation infrastructure in northern regions and frontier regions along the Indian border, which has resulted in the marginalization and regional underdevelopment due to the lack of infrastructure for economic growth. These underdeveloped areas also happen to be inhabited by nomadic populations and minority tribal groups. Third, migration between the two newly-independent nations of India and Pakistan during partition in 1947 created ethnic and linguistic demographic shifts in Pakistan, particularly evident in large cities and in the Provinces of Sindh and Punjab, which when politicized, leads to political instability (ICG 2017).

The impact of colonial-era history is visible in contemporary peasant protests and social land-based movements in Punjab and Sindh, in the separatist and independence movements in Pakistan’s northern regions of mineral-rich Balochistan, KP and FATA, and finally, in the presence of ethno-political violence in Pakistan’s largest urban city, Karachi. These violent conflicts over land and territory expose the fragility of the post-colonial state as federal, provincial and municipal administrative institutions struggle to govern in both densely-populated urban areas and scattered settlements in remoter ones.

First, the military is a significant landlord in both the Sindh and Punjab Provinces and in rural and urban areas. In rural areas, the military maintains a tenancy relationship with landless peasants on state farms that have existed since the colonial period. The state continues to allocate both forest and agricultural land to retired army personnel (to reward their service), heirs of martyred soldiers and to wounded military personnel (Jaffer 2016). There has been a long-running dispute between tenant farmers in central Punjab’s Okara District and the Pakistan Army. The disputed area includes 17,000 acres of agricultural land also known as the Okara Military Farm. The Government of Punjab owns the land, which includes seven farms, two dairy factories, a seed research institute and approximately 20 villages (Sheikh 2016). Okara farmers are part of and represented by the Tenants Association of Punjab (AMP, Anjuman Muzareen Punjab). The AMP is a movement of over one million landless peasants across 10 districts of Punjab Province that has been engaged in a struggle for land ownership rights. The struggle for secure land rights started in 2000 following the military’s introduction of a new piece rate system and new yearly lease agreements as well as unfavorable loan terms for inputs and daily expenses. Tenants who are sharecroppers refused to sign these new agreements and would not leave farms when verbally evicted. Other attempts at forced eviction took place in 2002 and 2003, as water and power supplies were disconnected (Sheikh 2016). At least 18 farmers have lost their lives since (Bano and Ghaffar 2014).

Protests by landless peasants across the Punjab have not lessened since 2000 and include protests at the Okara Farm, the Kulyana Estate and other military run farms in the Province (Sheikh 2016), which have turned violent. With the increase in power and militarization across Pakistani society, landless peasants and other groups fighting for resource rights are being detained under Anti-Terrorism Act as the military uses a broad interpretation of counter-terrorism law to arrest top AMP leaders and conduct village raids (Jaffer 2016; HRW 2016a). Twenty-four protesters were brought before the anti-terrorism court in April 2016 alone (HRW 2016a). Twenty-three peasant leaders and members were still imprisoned as of April 2017 (Iqbal 2017). AMP leaders are being branded as ‘anti-state’ with connections to the Government of India’s foreign intelligence unit, the Research and Analysis Wing or RAW (Jan 2016). In recent raids, police recovered hand grenades, rifles ammunition and foreign currency (Sheikh 2016). Conflicts between the military and peasants extend beyond land rights to fishing rights and environmental protection of the sea. In 2016, the head of the Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum was arrested by the Pakistan Rangers (a branch of the Pakistan Army). The exact nature of the charges was not released; however, Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum members had been actively protesting the construction of two coastal nuclear power plants built under a joint venture with the Government of China as well as protesting the acquisition of mangroves by the military-dominated Defense Housing Authority (DHA) (Jaffer 2016; ICG 2017).

The military not only controls land through large farms in rural areas, but controls land in urban areas through the DHA. The DHA is an autonomous body, managed by a military-dominated governing body, which controls and manages military cantonments across the country including in Karachi (ICG 2017). The DHA takes advantage of politicized politics and governance vacuums in urban areas such as Karachi to grab tens of thousands of hectares of land and construct exclusive residential communities (ICG 2017).

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRC), together with peasant and farmer’s rights groups, have demanded land reform; namely the redistribution of state land to landless peasants, with 15 acres being given to each landless family and women farmers receiving land shares equal in size to that of men. In addition to demands for land reform and putting an end to land grabbing by wealthy landlords, improvements to transportation and marketing infrastructure, access to canal water and workers’ rights and medical were among other demands (HRC 2014).

Second, violent extremism and inter-tribal conflicts in FATA and PATA, and a separatist movement in Balochistan along the border with Afghanistan, are territorial struggles that reflect long standing relationships between the Pakistan central government in the Punjab and communities that live in remote, peripheral areas. The Baloch have been waging a liberation struggle against the Pakistani state since the 1960s. Tribal group grievances pertain to decades of neglect as well as what is seen as a ‘forceful’ nation building strategy that attempts to incorporate tribal areas into the larger Pakistani body politic. Independence movements in Sindh pertain to struggles over irrigation water between Punjab and Sindh (Settle 2013).

Underlying conflicts in remote areas of the country whether, in the north or in the Thar desert in the south, are buttressed by social, cultural and political bias that systematically discriminates against tribal peoples and is evident in low scores on social indicators such as education and health, landlessness, environmental degradation and lack of participation in political decision making and a lack of livelihood opportunities (IFAD 2012). Sectarian violence and tribal conflicts have displaced upwards of three million people in FATA and KP for more than a decade (IDMC 2015).

Insurgencies and anti-terrorist measures have consequences for tenure relations in other areas of the country. As example, following the December 2014 massacre by armed militants at the Army Public School in Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, new legislation was introduced across the Federation and the Provinces to improve existing security frameworks. The Punjab Security of Vulnerable Establishments Bill 2015, for example, requires landlords to share information on tenants and temporary residents for the sake of security (PILDAT 2016a). Within forty-eight hours from time of delivery of possession of the rented premises, the landlord and the tenant will provide information to police about new inhabitants.

Third, recent and increasing ethno-political violence in the city of Karachi centers on control of land and territory that is partially enabled by the country’s land administrative system. Karachi’s coastal location, and its port on the Arabian Sea, has made the city a significant place for commerce, trade and economic growth. Karachi’s demographics changed significantly after partition, and politics since partition became increasing politicized as parties vied for power in a newly-independent Pakistan.

Migration to Karachi has continued as counter insurgency and military operations against separatist movements have forced jihadist groups such as the Taliban Movement of Pakistan to migrate south to establish recruitment and fund-raising offices in Karachi. The People’s Aman Committee from Balochistan has done so as well (ICG 2017). These groups, too, align themselves with local political groups and criminal gangs adding another layer of violence in the city. Political instability at the national level creates a power vacuum at the provincial and municipal level that elites, corrupt bureaucrats and criminal gangs exploited and that is exacerbated by uncoordinated land administrative institutions.

The large number of land-owning government agencies in Pakistan, each with their own standards and power to control land use and allocation, creates rent-seeking opportunities that are exploited by corrupt law enforcement and land and building authorities. In Karachi, for example, there are 17 land-owning government agencies. In the absence of a strong local government, there is uncoordinated urban planning (Sayeed et al. 2016; ICG 2017). The fragmentation of landholdings across municipalities, and the lack of coordination between land-owning agencies, create opportunity and space for the poor to squat on public lands. Private financiers and developers take advantage of this lack of coordination, colluding with and using political connections with bureaucrats to illegal access and regularize land for large scale real estate, commercial and housing development that benefits the upper middle class.

With this bias towards private development for the wealthy, the urban poor face a housing crisis that contributes to instability, corruption and violence, as they are pushed into densely populated areas such as squatter settlements called katchi abadis (KAs). More than 50 percent of the urban population lives in slums and squatter settlements (GOP 2015c) and at a population density of 4.500 persons per hectare (Shaikh and Nabi 2017; Siddiqa 2012). In Karachi, approximately 50 percent of the population resides in KAs that cover only 8 percent of the city’s land (Sayeed et al. 2016). Lack of government funds enable elites, criminal gangs and jihadist groups to capture not only of land as a bare asset, but also to control KAs and their resident population through the provision of public services such as transportation and electricity. The provision of this basic infrastructure to KAs allows mafias and extremist groups to create political patronage and recruitment networks that exploit the poor (Sayeed et al. 2016; United Kingdom 2017; ICG 2017). Furthermore, in the absence of any municipal regulation, the cost of private transportation in Karachi has increased by over 100 percent since 2000 (Shaikh and Nabi 2017). Taken together, all of these challenges reaffirm World Bank recent claims that urbanization in Pakistan is messy (Shaikh and Nabi 2017).

The nexus of politics, business interests, illegal land marketing and organized crime in urban extends to rural areas too (Crank and Jacoby 2015). There is considerable corruption in Education Departments across Pakistan connected to land mafias and powerful landlords. As provincial funds are often insufficient to improve educational infrastructure and the process of purchasing land legally is time consuming, wealthy land owners donate land to the Education Department or a politician in exchange for government employment for a family member. A Supreme Court inquiry into school closures across Pakistan found that many of the closed schools had been encroached upon by the donor as the promised employment was not provided or other powerful local interests occupy school premises. Schools also were closed when mutations in favor of the Education Department were not attested. The Education Department had filed against encroachers in either high or civil courts in only a few cases. Otherwise weak school administrations are unable or unwilling to evict encroachers (Supreme Court 2013). Police have been empowered to counter organized crime (mafias) forcefully grabbing land, which significantly increases their workload and strains their institutional capacity and resources (HRW 2016b; ICG 2017).

In addition to large-scale, violent land conflicts, smaller but nevertheless significant inter- and intra-familial land conflicts exist with respect to boundary, inheritance, succession and tenancy. Such land disputes are addressed by the revenue court system (United Kingdom 2017). Major causes of land disputes are inaccurate or fraudulent land records, erroneous boundary descriptions that create overlapping claims and multiple registrations to the same land by different parties. Up to 80 percent of the civil case load has to do with land titling and acquisition disputes arising out of land grabbing and misappropriation of property (United Kingdom 2017).

Local land disputes are heard at the tehsil level (a level of local government similar to a county) by the tehsildar, the officer responsible for the collection of land revenue and land administration. A Chief Settlement Officer and the provincial-level Board of Revenue are the appellate authorities within the revenue court system. The revenue court system, which is designed to provide a specialized and local resolution of disputes, has been criticized by landholders as time-consuming, complex and subject to corruption. Land administration offices do not publish procedures for bringing a claim, documentation of land rights is often missing, land records maintained by the local authorities are often incomplete or of questionable validity and land administration officials such as the patwari often do not appear to provide evidence (Ali and Nasir 2010).

Pakistan’s formal court system also has jurisdiction to hear land cases, creating a parallel structure of courts. Land disputes are the most common form of dispute filed with the formal court system, perhaps in part because filing a case may stay a pending revenue court proceeding. Between 50 percent and 75 percent of cases brought before lower-level civil courts and the high courts are land-related. Pakistan’s judiciary is hampered by low pay, poor training and a large volume of cases. Credible evidence of land rights is often nearly impossible to obtain. Land cases can take between 4 and 10 years to resolve, with the party in possession of the land delaying adjudication in order to prolong the period of beneficial use. Appeals are common (see Box 4; USAID 2008; Dowall and Ellis 2007; Ali and Nasir 2010).

Given the shortcomings of the court system and with rising secular tensions across the country, falsely accusing one party in a dispute of blasphemy is becoming another tactic to settle localized land conflicts. Given the severe nature and punishment for blasphemy and the fact that blasphemy charges can often lead to mob violence against the accused, especially if the accused is from a minority group, a party accused of blasphemy, even if falsely-accused, is likely to back down (United Kingdom 2017).

Reforms of the land administration system, such as digitization of land records, once completed, has the potential to overturn some of the corruption and efficiencies in the land conflict resolution system. Digitization of records and their central storage at Land Record Management and Information Systems (LARMIS) service centers should make land records more easily accessible to land owners, increase transparency and reduce some of the delays and corruption associated with the previous patwari system. Given that the LARMIS process has only been completed in one province with remaining provinces still in the process of completing the digitization process, it is too early to tell what effect digitization of records will have on land-related conflict and associated corruption within the system. Anecdotal evidence suggests that transparency has increased and corruption has reduced. Yet, given that the justice system is overburden, land-related cases may still take years to resolve (Ali and Nasir 2010; see Box 4).

The vast number of land-owning institutions that converge in one area is problematic given the fact that these institutions are uncoordinated and follow their own individualized standards and mandates. In the absence of strong local government, corrupt government officials, land mafias and the political and economic elite take advantage of these inconsistencies and gaps in land management. The state’s land-owning institutions, therefore, contribute to localized conflict and violence.