Introduction

In October and November 2020, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded Integrated Land and Resource Governance (ILRG) task order provided technical and financial support to Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) to facilitate gender integration in the election process of community natural resource governance structures in the game management areas (GMAs) around the North Luangwa National Park, Zambia. This intervention aimed at increasing women’s participation in village action groups (VAGs) and community resources boards (CRBs), serving as a pilot to engage stakeholders, including the Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) and the Zambia Community Resources Board Association (ZCRBA), on broader reforms to increase gender equality in community natural resource governance in Zambia. The approach included convening key stakeholders before and during the election process to support women and address practical and social barriers to their participation.

This report details the strategies used and the outcomes in the election results, and reflects on lessons learned, challenges, and opportunities for scaling the approach. The report further makes recommendations for stakeholders to facilitate gender-responsive election processes to increase opportunities for women’s participation in natural resource governance in Zambia and elsewhere.

Background

Natural Resources and Gender Equality

In Zambia, women and men have distinct traditional social roles and responsibilities at the household and community level regarding their access to and use of the local environment and natural resources. Likewise, depletion of natural resources tends to impact women and men differently. Despite this, gender inequalities and the different ways men and women access, use, control and their knowledge of natural resources are often ignored in natural resource management, thereby undermining the effectiveness, impact, and sustainability of development and conservation efforts. By failing to adopt gender-responsive approaches, programs in the sector fail to sufficiently address the different needs of women and men and consider their unique concerns, points of view, and knowledge.

There is growing evidence in Africa and elsewhere that inclusion of women in natural resource governance has significant positive effects on conservation and development outcomes, though this has been examined primarily in the forestry sector. A comparative study in East Africa and Latin America found the presence of women in community forest governance structures to enhance positive behavior and forest sustainability (Mwangi et al., 2011). In Asia, increasing women’s representation in community forest governance institutions improved resource conservation and regeneration (Agarwal, 2009). The benefits of women’s participation were linked to their indigenous knowledge of the forest, greater rule compliance and adoption of sustainable practices, and greater cooperation among women. Increased participation in natural resource governance can be a pathway for wider empowerment of women in the household and in the public sphere, also leading to opportunities for growth in families’ income from economic activities related to natural resources. In addition, private companies in value chains related to natural resources are more likely to certify products and practices if women have active participation in resource governance (Beaujon Marin & Kuriakose, 2017).

The Government of Zambia recognizes the need for community involvement in the governance and conservation of natural resources and over the past decades has promoted devolution approaches that enable communities to share responsibilities for natural resource management. The legal and policy framework, including the 2015 Wildlife Act No. 14 and the 2018 National Parks and Wildlife Policy, provide for community participation and gender equality in accessing, controlling, benefiting from, and managing natural resources. The policy has an explicit objective of mainstreaming gender, HIV/AIDS, and youth empowerment in wildlife conservation, creating equal opportunities and conditions for women, men, and youth to benefit equally and reduce inequities in conservation. The 2014 National Gender Policy and the 2016 Gender Equity and Equality Act No. 22 ensure gender equality and offer redress for existing gender imbalances by tackling gender-based violence (GBV) and gender disparities in positions of decision-making at all levels and across sectors. Despite progress in policy reforms, women’s actual and meaningful participation in natural resource governance and benefit sharing have lagged behind and remain a challenge.

Community Resource Governance in Zambia

Community governance institutions offer an important opportunity for promoting gender equality and women’s participation in the natural resources sector. In Zambia, such institutions are CRBs for wildlife management and community forest management groups (CFMGs) for forestry. DNPW manages national parks and has responsibilities in GMAs and in open areas where wildlife resides. GMAs were established primarily to serve as buffer zones around national parks, which is where most CRBs are established to co-manage wildlife resources.

CRBs are formed from the lower-level VAGs, which comprise not more than 10 elected members and are responsible for deciding on community needs and interests in the utilization of wildlife resources. The members with the highest votes from all VAGs in a chiefdom then form the CRB, which is a higher-level executive body of the community that also has 10 members. The CRB is the decision-making and coordinating body of the community. There are 77 CRBs in the country, grouped together in four regions to form the membership of the regional CRB associations and at the national level, the ZCRBA. Each regional CRB association has a leadership position in the ZCRBA National Executive Committee. Some of the key functions of the ZCRBA are to coordinate the CRBs, unify CRBs to advocate and address collective issues, and provide capacity building to the membership.

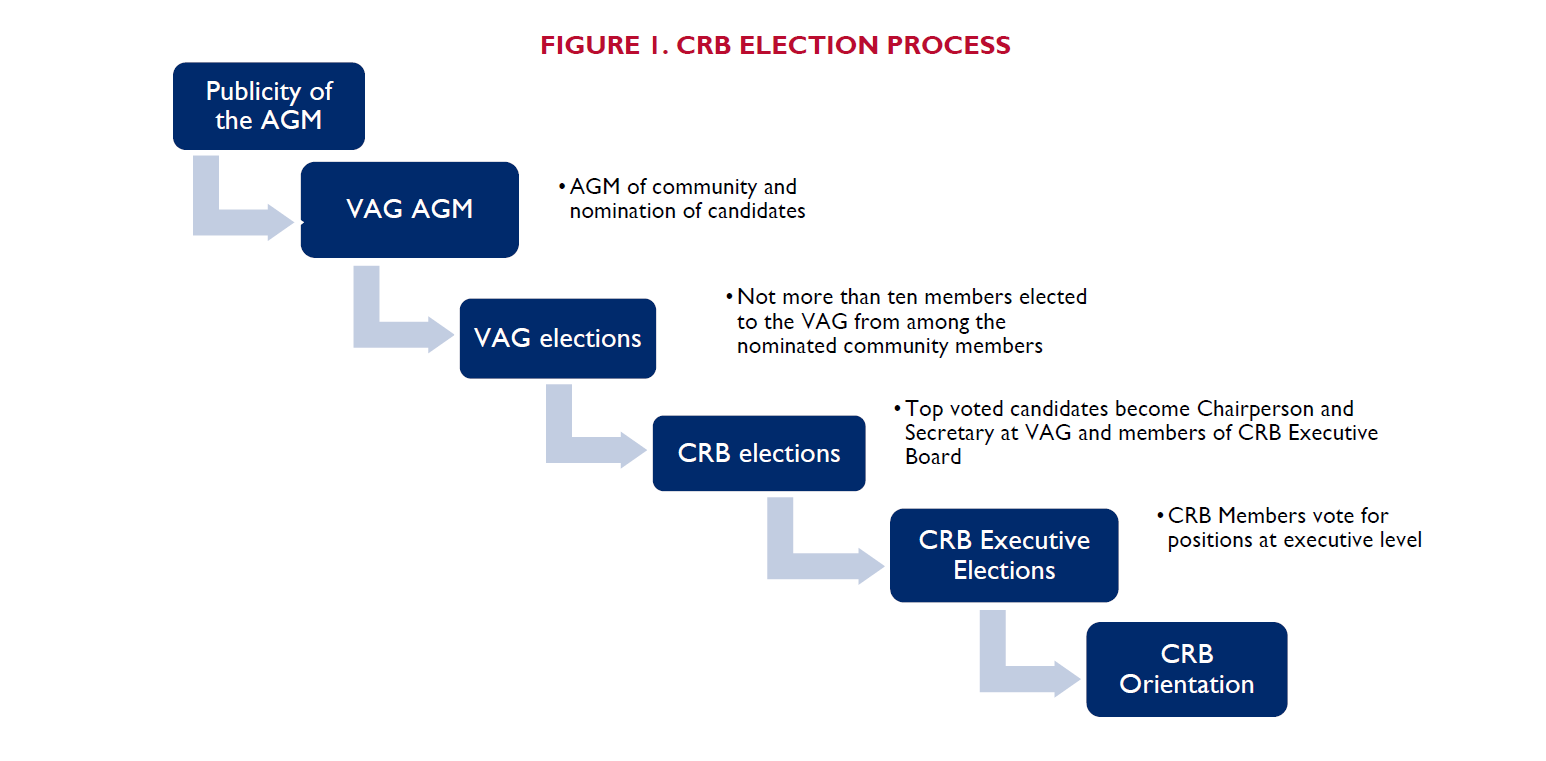

The election process for VAGs and CRBs is governed by the 2013 CRB Election Guidelines, developed by DNPW. The following figure illustrates the steps in the CRB election process:

According to the CRB Election Guidelines, the VAG and CRB positions are up for election every five years, though in practice this happens every three years. The election process starts with publicity about the annual general meeting (AGM) a few days prior to the meeting. All community members are eligible to attend the VAG AGM meeting. Publicity is done through megaphones and headpersons informing people of the date of the AGM, the agenda, and the venue. During the AGM, all individuals interested to run in the election are required to file their nominations, receive an animal symbol as their identity for campaigning and receiving votes, and immediately start the campaign to get elected. The campaign is often for a short period of two to three days. Experience from previous elections show that women are often not reached by awareness-raising efforts and lack information about the process and criteria to participate in the election. The short campaign period also disadvantages women, who have limited financial resources and competing household responsibilities.

According to the CRB Election Guidelines, the VAG and CRB positions are up for election every five years, though in practice this happens every three years. The election process starts with publicity about the annual general meeting (AGM) a few days prior to the meeting. All community members are eligible to attend the VAG AGM meeting. Publicity is done through megaphones and headpersons informing people of the date of the AGM, the agenda, and the venue. During the AGM, all individuals interested to run in the election are required to file their nominations, receive an animal symbol as their identity for campaigning and receiving votes, and immediately start the campaign to get elected. The campaign is often for a short period of two to three days. Experience from previous elections show that women are often not reached by awareness-raising efforts and lack information about the process and criteria to participate in the election. The short campaign period also disadvantages women, who have limited financial resources and competing household responsibilities.

During the election, representatives of the candidates sit in as observers throughout the process to ensure transparency; votes are openly cast using symbols. Voters line up outside the voting room and in small groups are allowed to enter, pick the symbol of the candidate of choice, put a thumb print on it, and cast the vote in a transparent box. The top two candidates with the highest number of votes in the VAG election automatically qualify to represent the community at the CRB executive level or board. In the case of CRBs with more than five VAGs, only the top voted candidates get onto the CRB board. The elections for CRB board positions generally happen shortly after concluding VAG elections. The CRB Election Guidelines do not set this timeline, which is left to the electoral committee to determine based on various factors, among them available resources, geographical coverage of the CRB, and capacity within the chiefdom.