As the Colombian government strives to put women at the forefront of land rights and restitution, USAID teamed up with a group of women to transmit their stories in their own voices and explain to rural families the land restitution road map.

As the Colombian government strives to put women at the forefront of land rights and restitution, USAID teamed up with a group of women to transmit their stories in their own voices and explain to rural families the land restitution road map.

Deyis Carmona Tejeda is not an actress. She acted for the first time when she was 43, inspired by displaced women who also suffered the ravages of war.

Behind the microphones, she had to let go of her own story for a moment in order to get into “Somebody Else’s Body”—as the play is called—and give life to Juana, the protagonist of a real-life story that recounts how she was displaced from her land by violent groups, how her son disappeared and was murdered, and how she lived under constant threat in addition to suffering abuse by her husband.

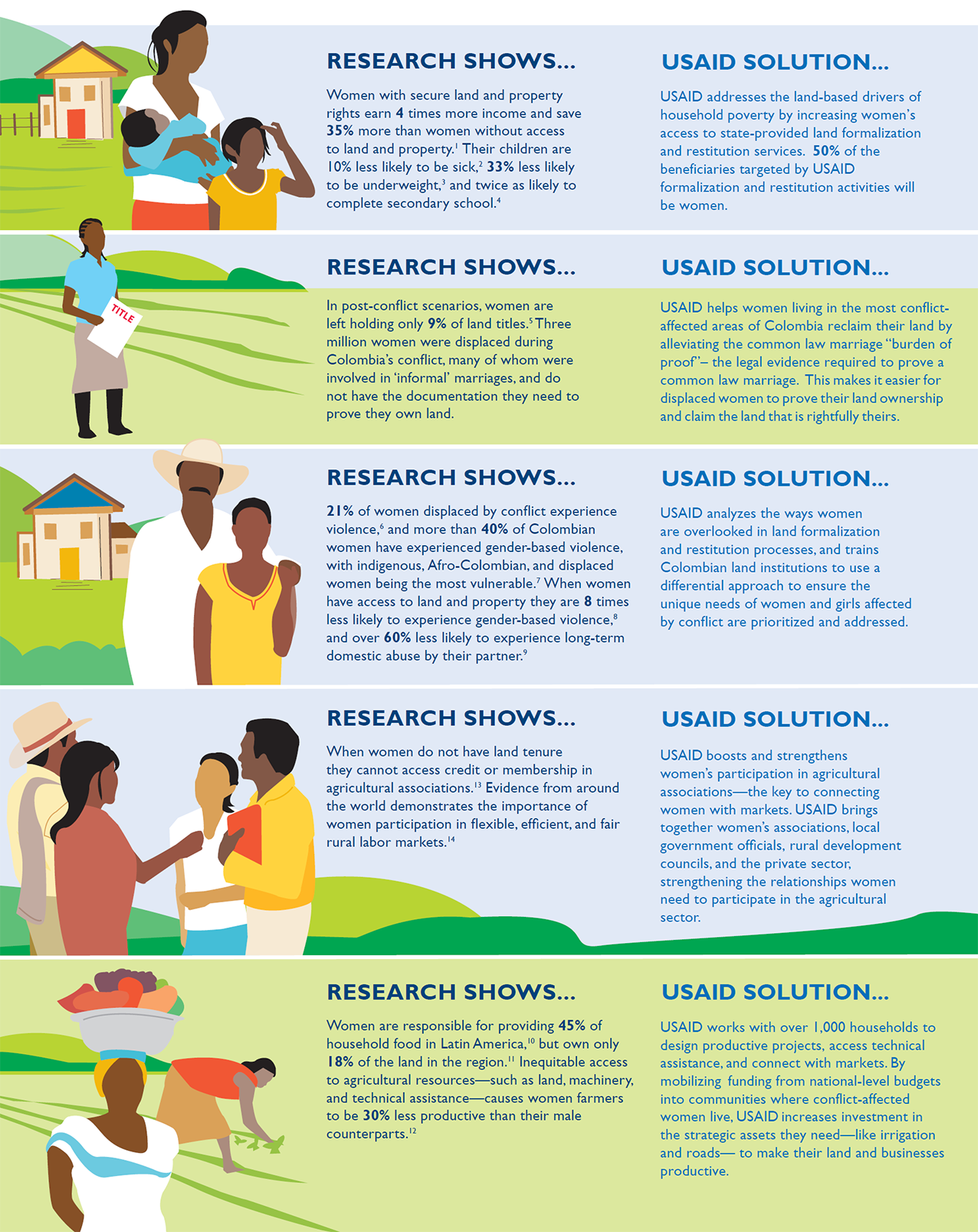

The play is one of the 12 radio dramas from the series Land Rights: Stories Made by Women for Women, directed by Colombian actor Daniel Rocha. The radio dramas are meant to disseminate information about land-related services available to women and victims of the conflict. The strategy is part of a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) program that has been working with the Colombian government since 2014, especially with the entities involved with land administration, like the Superintendence of Notary and Registry, the National Land Agency, and the Land Restitution Unit.

Women and War

Through female voices, these radio dramas guide other women in Colombia on how to formalize their property, file land restitution claims, and acquire funding and technical assistance for agricultural projects.

More than 70 women—including farmers, Afro-descendants, and members of indigenous communities—from 18 municipalities in Cesar, Sucre, Bolívar, Cauca, Meta, and Tolima were part of creating the scripts and storylines. The stories have been broadcast on 36 radio stations in these departments.

“We received training, and our work with USAID strengthened those skills. We think this is important because those same land institutions are being strengthened through this program, and by working with us, the program scored a goal by working with the victims in rural areas,” noted Deyis.

Many of the women who participated in the radio series have been or are currently involved in the land restitution process. Since their release, the radio dramas have reached more than six million listeners in 96 municipalities. In addition to airing on radio stations, the dramas have been disseminated via CD.

Listen to a radio theater show here: https://soundcloud.com/usaidlrdp

War in the Flesh

The drama starring Deyis is not much different from her real-life story. In 1996, when she was just 18 years old, she fled her home in rural El Copey to urban Valledupar out of fear for her life. She had begun to stand out as a leader in the community, and that was dangerous. Deyis returned, but was once again displaced in 2000 by threats from the paramilitaries. In 1998, her mother was kidnapped by guerrillas, and their house in El Copey was burned down.

For 15 years, she lived in Valledupar, where she managed to finish a technical course to become a clerk. “The only good thing about it was that I was able to train and get a proper education,” she said.

Despite personal progress, her experiences with violence and intimidation continued. In 2000, she returned to her plot and found that other family members had also been displaced, including her younger sister, who subsequently disappeared at the hands of paramilitaries. Deyis later learned that her sister’s remains had been buried in a mass grave along with those of 21 others.

“From the moment that she disappeared, I made a point of seeing her disappearance as something that would give rise to constructive behavior and not just painful memories,” says Deyis.

Supporting Other Victims

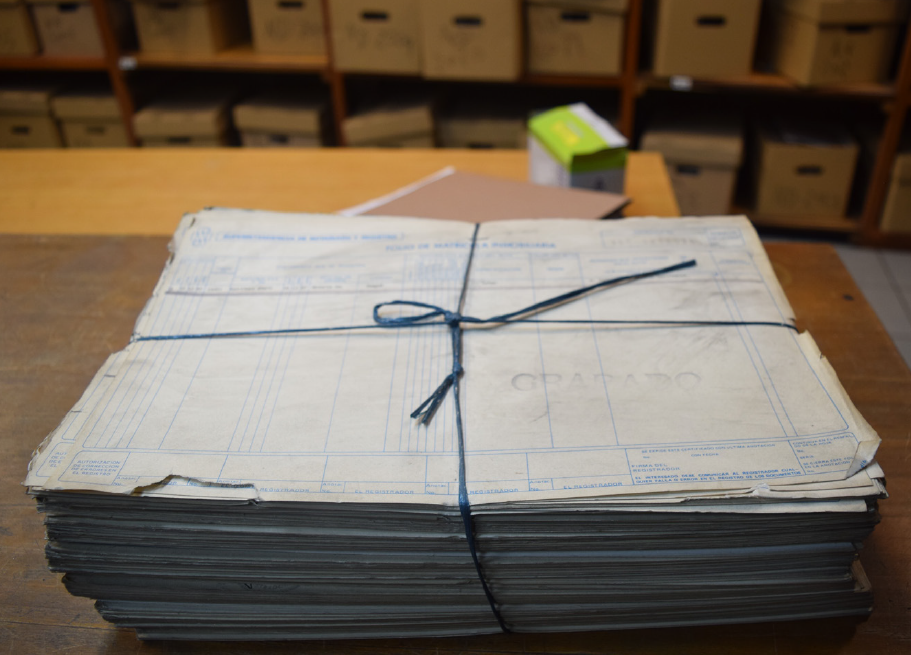

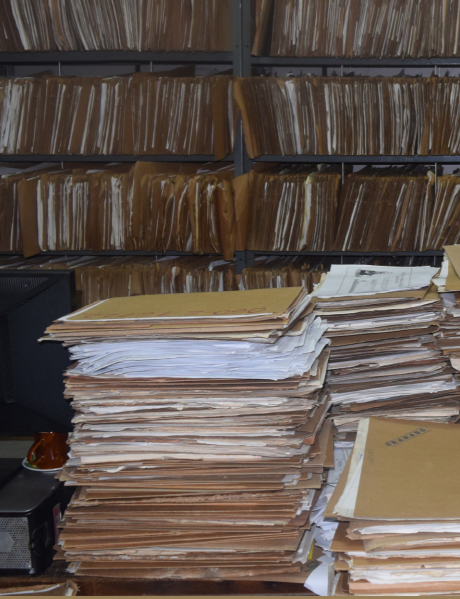

Displaced women face disproportionate difficulties in proving that they own their land, because women are usually excluded from property titles. For a woman to demonstrate that she is an owner, she must initiate a judicial process in which, if she had been in a civil union, she is forced to provide testimony and witnesses who can prove her relationship with her spouse—and therefore, with the property.

“It is easier for men to prove they are owners of land. In order to claim their rights, they only need to show the records,” said Deyis.

Nowadays, Deyis acts as spokesperson of the El Copey Village Victims Association, an organization that she created five years ago when she realized that nearly the entire village had been a victim of land dispossession. The group, which is made up of 60 families, works to address forced displacement, disappearance, and land dispossession.

“With the radio dramas, we are instruments that help the institutions reach and help women victims. We are very lucky because we have enjoyed the support of other institutions, but there are women who still don’t know that options exist,” asserted Deyis.

One of the objectives of Colombia’s Victims Law is to make women more visible in terms of land administration and the impacts of the conflict, according to Jorge Chávez, territorial director of the Land Restitution Unit in Cesar and Guajira. USAID’s radio dramas contribute to these goals by giving women a roadmap for compensation. Today, 35 out of every 100 requests for land restitution in Cesar are made by women.

“For the LRU, this support is very important. Land informality and the separation of women from their land ends up being a major difficulty in terms of the land restitution process,” explains Chávez. “Together with USAID, we’ve been able to show that not just women but other diverse sectors of society have been uniquely affected by the armed conflict.”

“Many women are not aware of their rights. And despite our work as an association, there are still things that we need to learn. The social approach of creating radio dramas has given us an amazing experience,” says Sintya Bedón Murillo, a member of the Esfuérzate Association in Montes de María and one of the participants of the radio drama entitled “The Aroma of Land in a Bowl of Sancocho.”

“I will exercise my rights, and this experience has given me the strength to demand them, even if my name does not appear on the land documents.”

—Deyis Carmona Tejeda.