Registration of Diamonds in Forecariah: First Time Ever in the Prefecture

Spurred by a massive influx of refugees from Sierra Leone and Liberia, artisanal diamond mining commenced in the 1990s in the Forecariah prefecture in Guinea and along the alluvial river courses of this coastal area.

Artisanal diamond mining in Forecariah has long been unorganized with little to no supervision by the government mining agency. Incoming diamond miners simply negotiated access to a piece of land from customary landowners and begin digging without regard for the laws and regulations governing this sector. The Forecariah Prefecture Director of Mines tried in vain with only one staff member and a volunteer to supervise more than twenty diamond mining sites with very limited means at his disposal. In effect, the state was truly absent in the majority of the diamond mining areas.

With the arrival of the Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development II program (PRADD II), the Ministry of Mines and Geology and the project staff placed a strong emphasis on expanding the presence of government in the artisanal diamond mining areas of the Forecariah Prefecture. PRADD II focuses on selecting and training a cadre of three young ministry geologists, called by the project “Junior Experts,” to take up positions in the prefecture and thereby strengthen the presence of the state. The project works very closely with the ministry to carry out training on the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS), provide hands-on instruction in diamond identification and registration in production notebooks, and use eTablets and specially configured software to register diamonds collected at mining sites.

From March to June 2015, 292.83 carats of diamonds (including 156.82 ct. of jewelry quality, 130.98 ct. of industrial quality and 5.03 ct. of boart quality) were registered. Even though the diamonds so far found in Forecariah are small in size compared to those from the mining major zone of Banankoro in the southeast of the country, the progressively expanding registration of diamonds strengthens Guinea’s compliance with the Kimberly Process.For the first time in Forecariah, diamonds are now beginning to be registered in compliance with Kimberly Process Certification Scheme requirements. In expressing his satisfaction about this effort, the National Director of Mines stated that “to date, our young experts are registering diamonds in the field and transmitting the data to us instantaneously. We receive everything in real time.” These procedures assure that diamonds are not being illicitly traded and used to finance wars and violent conflicts. “Thanks to the registration process set up by the project, we were able to locate a diamond from a site that has an invalid license,” noted the Head of the ASM Division in a conversation with the PRADD team. Trust is being progressively built between the Junior Experts and the diamond miners. One of the Junior Experts noted that “80% of miners are allowing their findings to be registered.” The Director of Mines added: “when miners understood that the Junior Experts were not there to take their diamonds away from them, they immediately accepted registration of their findings. When they were told that they will not be asked to pay taxes and registration will be discreet, and when they understood that all we need is to capture the statistics of production, they accepted immediately.” Gone are the days of secrecy when artisanal diamond miners refused to register diamonds. “Even if the diamond is a half carat, miners reach out to us for registration. Initially, miners were opposed to having their photos taken but thanks to the trust that is settling in, they now accept and require their photos to be taken for inclusion in the database,” concluded one of the Junior Experts.

From March to June 2015, 292.83 carats of diamonds (including 156.82 ct. of jewelry quality, 130.98 ct. of industrial quality and 5.03 ct. of boart quality) were registered. Even though the diamonds so far found in Forecariah are small in size compared to those from the mining major zone of Banankoro in the southeast of the country, the progressively expanding registration of diamonds strengthens Guinea’s compliance with the Kimberly Process.

Much more work remains to further address illicit mining and smuggling across the nearby porous border with Sierra Leone. But, this first step, the registration of diamonds through official government channels, is a far cry from the chaotic situation of the early 1990’s when a free-for-all reigned in Forecariah. Certainly, more work is needed to incentivize miners to rehabilitate the land with improved mining techniques and to strengthen relations between government and customary land owners in diamond rich mining areas. But this first steps needs to be applauded – the core objective of the PRADD II program in Guinea.

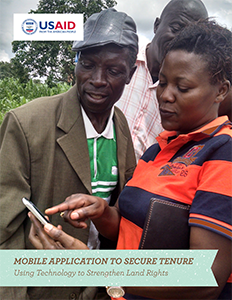

Download the Mobile Application to Secure Tenure (MAST) Brochure.

Download the Mobile Application to Secure Tenure (MAST) Brochure.