Analyse de l’Impact des Certificats de Droits de Propriété dans les Zones d’Exploitation Artisanale du Diamant au Sud-Ouest de la RCA

Resume Executif

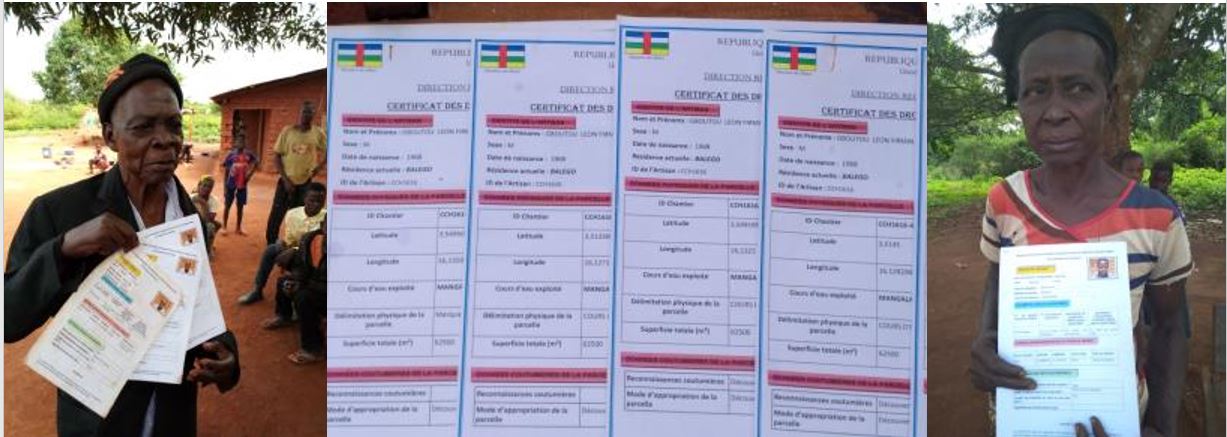

L’objectif du projet Droits de Propriété et Artisanat Minier (DPAM) financé par l’USAID en République Centrafricaine (RCA) est de renforcer la gouvernance des ressources naturelles et des droits de propriété des hommes et femmes dans les communautés minières, à travers une approche multidisciplinaire incluant des pratiques et outils ayant fait leurs preuves. Pour développer et implémenter des activités autour de la formalisation des droits de propriété et de la gouvernance des terres dans les zones d’exploitation minière artisanale, le projet USAID DPAM veut s’inspirer de l’expérience du précédent projet Droits de Propriété et Développement du Diamant Artisanal (DPDDA). Le projet DPDDA a mis en place entre 2007 et 2012 un processus de reconnaissance des droits coutumiers de propriété sur les chantier miniers, appelé initialement Certificats DPDDA visant à documenter et formaliser les droits fonciers coutumiers des artisans miniers tout en établissant une base légale de droits légitimes, réduire les conflits autours des chantiers miniers et créer une meilleure visibilité et traçabilité autour de l’artisanat minier de diamant. Un total de 1380 Certificats DPDDA ont été délivrés au terme d’un processus de participation volontaire des artisans miniers et une validation publique faite au niveau des villages dans la Lobaye, Mambéré Kadei et Sangha Mbaéré, reconnaissant et clarifiant l’appartenance des parcelles de terres à vocation d’exploitation minière à des chefs de chantiers bien identifiés. Toutefois, une ambigüité persistait sur le rattachement juridique de ces documents au terme du projet DPDDA, car il n’est pas clair qu’ils aient été délivrés en vertu de la législation foncière du Code minier. Le Ministère des Mines et de la Géologie (MMG) s’est initialement opposé à cette innovation rendue nécessaire par l’importante demande clarification des droits individuels ou collectifs sur les chantiers miniers pour éviter des conflits.

L’étude d’impact des Certificats conduite du 1er au 25 juillet 2019 a porté sur les objectifs suivants :

- Évaluer la perception, les effets et l’utilité des Certificats de droits de Propriété délivrés par le projet DPDDA I sur la protection des droits des artisans miniers et la gestion des conflits.

- Analyser les ambiguïtés juridiques autour des Certificats au regard de la législation minière et des réalités des arrangements fonciers coutumiers.

- Elaborer des recommandations pour la définition et la mise en œuvre des activités d’appui à la formalisation des droits individuels des artisans miniers et pour l’amélioration de la gouvernance foncière dans le secteur de l’exploitation minière artisanale et à petite échelle.

L’étude a utilisé une combinaison d’analyse documentaire et juridique du contexte de la formalisation foncière en zone minière, avec des entretiens semi-structurés de 125 artisans miniers provenant de 8 villages (64 hommes et 7 femmes), étant bénéficiaires et non bénéficiaires des Certificats, et avec les autorités minières déconcentrées de Boda et Nola. L’équipe a fait des interviews avec un village contrôle (Bomandoro) qui n’avait pas participé dans la certification et ensuite deux villages récipients (Mboulaye 2 et Mboulaye 3). Des résultats préliminaires ont été analysés lors d’un atelier de réflexion sur les options de formalisation des droits de propriété au regard du cadre juridique national avec les principales parties prenantes des différentes institutions gouvernementales impliquées dans la gestion foncière au niveau national.

PRINCIPALES CONCLUSIONS DE L’ETUDE D’IMPACT

La pertinence et l’utilité des Certificats et des informations contenues sur les différentes versions sont avérées pour la reconnaissance des droits fonciers des artisans miniers et la gestion des conflits ; cependant les ambiguïtés existent sur des questions de formes, l’administration des certificats, et le rattachement légal.

- L’expérience menée par le projet DPDDA visant à délivrer des certificats de droit de propriété à certains artisans miniers a permis la mise en place d’un outil simple de constatation des droits des artisans sur les parcelles exploitées.

- Les Certificats DPDDA ont permis de manière générale de clarifier l’appartenance et /ou l’occupation individuelle sur des parcelles de terres à vocation d’exploitation minière à travers un processus communautaire participatif et transparent d’identification du propriétaire de la parcelle, de clarification des modes d’acquisition de cette parcelle et de validation publique faite dans les villages.

- Le processus de validation publique devant les autres artisans miniers et les chefs de villages et de groupe ont conféré à ces documents un caractère général et une reconnaissance locale forte des droits coutumiers sur les chantiers.

- Les Certificats ont grandement permis de déterminer les limites des chantiers miniers en anticipant sur les conflits ou en résolvant les conflits qui se sont posés sur ces parcelles. Les communautés et les autorités des mines l’utilisent encore actuellement comme preuve de propriété dans la résolution de plusieurs cas d’empiètement sur les parcelles ou de transfert des chantiers à des tiers ; aussi bien les chefs de village que les Chefs de Service de Mines reconnaissent que la possession de certificats est un avantage réel lorsqu’ils sont saisis pour résoudre des cas de litiges.

- Les certificats ont contribué au renforcement de la conformité avec le processus de Kimberley. Les activités de sensibilisation autour des Certificats ont grandement contribué à la sensibilisation des artisans miniers sur la nécessité d’obtenir des documents miniers pour être conformes à la chaîne légale de production du diamant que les miniers devaient toujours payer la taxe obligatoire « patente » et autres autorisations d’exploitation minière. Les messages de sensibilisation sur le fait que le certificat n’est pas un document minier a servi entre autres facteurs de catalyseur pour l’acquisition de la patente pour plusieurs artisans miniers. Presque toutes les personnes interviewées savaient quelle documentation obtenir pour un artisan minier.

- Plusieurs ambiguïtés liées aux termes utilisés dans les deux versions des documents de formalisation, principalement les termes « Certificats de droits coutumiers » et « dossier de droits » , et à la procédure de mise en place de cette activité ont été notées.

- Pour la quasi-totalité des personnes interviewées y compris l’administration minière aux niveaux déconcentré et central, le processus et les Certificats qui en ont découlé sont considérés comme une activité et un document du projet DPDDA : les institutions des mines ne l’ont utilisé ni pour suivre la production et la commercialisation du diamant ni pour suivre et encadrer les artisans miniers.

- Il n’existe pas au niveau local des registres clairs listant les artisans miniers ayant reçu les certificats, ni des procès-verbaux de validation du processus.

- Aucune demande de Certificat n’a émané des artisans miniers après le projet DPDDA et l’administration minière n’en a pas délivré. En outre, au vu des circonstances de crise de 2013 ayant entrainé la fermeture inopinée du projet DPDDA, il n’y a pas eu une transmission encadrée et effective des compétences et des technologies au ministère des mines pour le suivi effectif du processus.

- Les Certificats ont été abordés comme des documents de reconnaissance de la propriété foncière gérés par l’administration minière, le mettant dans une posture non conforme aussi bien à la loi foncière qu’à la loi minière. En effet, les Certificats DPDDA semblent ne pas trouver une base juridique, permettant de rendre légal et plus utile, leur usage par les artisans miniers. Il existe un vide juridique dans les textes miniers sur la prise en compte des droits coutumiers des artisans sur les parcelles qu’ils exploitent. Ni le Code Minier ni son Décret d’application ne définissent de manière non équivoque les modalités concrètes de formalisation des droites de propriétés d’un artisan minier vertu de la coutume ; de même, ces textes restent muets sur comment un artisan minier peut le cas échéant, faire prévaloir ses droits coutumiers de propriété, s’ils sont reconnus comme étant antérieurs au processus d’octroi d’une autorisation d’exploitation artisanale sur une zone donnée.

RECOMMANDATIONS

Les recommandations sont élaborées pour informer le projet USAID DPAM pour une poursuite des activités de formalisation des droits fonciers des artisans miniers entamées par le DPDDA selon des modalités adaptées au contexte actuel dans un court terme pouvant aboutir à des réformes dans le moyen terme.

Dans le court terme

- Renforcer l’engagement entre le projet USAID DPAM et le gouvernement centrafricain dans le cadre d’une convention à consolider les acquis du projet et continuer la délivrance de ces documents de formalisation des droits fonciers des artisans miniers à titre pilote dans une ou plusieurs nouvelles zones.

- Reformuler le document de formalisation en « attestation locale de reconnaissance de parcelle minière » (intitulé suggéré), délivrée à un artisan individuellement ou collectivement à travers une coopérative minière comme début de preuve de l’usage de telle ou telle parcelle par l’artisan minier ou la coopérative. Un tel document continuera à renforcer les droits des artisans miniers sur les parcelles, et à jouer un rôle clé dans la réduction des conflits sur les parcelles et à donner une position favorable aux artisans miniers pour la négociation avec des exploitants semi industriels ou industriels de plus en plus nombreux dans la région. Cette approche aurait l’avantage de se conformer aux textes en vigueur en attendant la mise en place de nouvelles dispositions sur l’exploitation minière dans le pays.

- Réviser le formulaire de documents de formalisation des claims miniers en insérant une carte de localisation de la parcelle, fournissant des informations sur la taille, les zones minées, les zones non minées, les parcelles voisines, et les utilisations. Sous PRADD I, les données de localisation SIG étaient enregistrées pour chaque fosse sous le contrôle d’un mineur artisanal, mais pas les limites, car les appareils GPS de l’époque n’étaient pas assez précis. Les limites de la frontière ont été convenues entre la communauté et les mineurs voisins grâce à un processus de consultation publique. En l’absence de litige, le claim était considéré comme exact. Le même processus pourrait utiliser des technologies basées sur le GPS et des tablettes, comme celui mis à l’essai en Côte d’Ivoire sous PRADD II pour cartographier les plantations de noix de cajou ; à partir de là, une documentation foncière a été préparée, générant un formulaire précisant les droits fonciers et les limites générales. Étant donné que la précision du SIG a considérablement augmenté, il devrait maintenant être plus simple de cartographier les limites. Cependant, des normes de précision et d’exactitude doivent encore être négociées avec le ministère des Mines et de la Géologie, mais compte tenu des limites technologiques, ces limites ne doivent pas être d’une précision extraordinaire. Les relevés GPS à eux seuls ne sont peut-être pas assez précis pour satisfaire les autorités, mais comme précédemment testé dans le cadre du PRADD I, les accords entre villageois sur les limites des revendications sont extrêmement précis. Ce qui compte, ce sont les accords communautaires. La mise en place de ce cadastre au niveau du village pourrait contribuer à la réflexion sur la manière de développer et de reproduire le processus à plus grande échelle.

- Intégrer la formalisation comme une approche générale de gestion des parcelles minières et à vocation minières ainsi que les relations entre les différentes parties prenantes dans les Zones d’Exploitation Artisanale minière (ZEA). Les informations physiques, coutumières et géographiques sur les documents de formalisation permettront une meilleure administration des ZEA, avec une reconnaissance des espaces avec superposition d’autorisation et de permis et de suivi par l’administration minière de la production de diamant dans les ZEA en comparaison des produits déclarés.

- Documenter systématiquement le processus aussi bien au niveau local que national pour utiliser les leçons apprises pour renforcer l’appropriation locale et assurer la réplication du processus si nécessaire.

Dans le moyen terme

- Engager des discussions sur la réforme de la législation minière pour prendre en compte les éléments liés au droit de propriété coutumier des artisans miniers, lequel droit pourrait découler d’un héritage, du travail investi ou d’un achat. Cette question apparait incontestablement et essentiellement comme relevant de la responsabilité du Gouvernement, même si quelques partenaires pourraient lui apporter leur concours afin de parvenir à cette fin.

The Artisanal Mining and Property Rights (AMPR) project supports the USAID Land and Urban Office to improve land and resource governance and strengthen property rights for all members of society, especially women. Its purpose is to address land and resource governance challenges in the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector, using a multidisciplinary approach and incorporating appropriate and applicable evidence and tools. The USAID AMPR project began in September 2018, and will run for 3 to 5 years, conducting most activities in the Central African Republic.

The Artisanal Mining and Property Rights (AMPR) project supports the USAID Land and Urban Office to improve land and resource governance and strengthen property rights for all members of society, especially women. Its purpose is to address land and resource governance challenges in the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector, using a multidisciplinary approach and incorporating appropriate and applicable evidence and tools. The USAID AMPR project began in September 2018, and will run for 3 to 5 years, conducting most activities in the Central African Republic.