Background

In Tanzania, land is a crucial asset that supports livelihoods and enables individuals and households to expand their economic opportunities. However, weak land rights protections and a lack of documented ownership or use rights have long been seen as sources of local disputes, constraints to how farmers use and invest in their land, and barriers to household economic growth. In 1999, the Government of Tanzania enacted land reforms that laid the foundation for recognizing farmers’ customary land use rights. Under the 1999 law, individuals who use or occupy village land have the right to obtain formal documentation of their customary land use rights via a Certificate of Customary Right of Occupancy (CCRO), a legally valid and transferrable document that the local government issues. Yet the process of certifying land and issuing documentation has been slow and most Tanzanian villagers still lack formal documentation of their land rights. Reasons for this include limited government resources, lengthy and costly land-use planning and surveys, and a lack of village capacity to complete the steps required for a CCRO to be issued.

In 2015, USAID launched the four-year Land Tenure Assistance (LTA) activity to support 30 villages and the Iringa district land office in registering customary land ownership and increasing local understanding of land use and land rights. LTA worked to achieve systematic CCRO documentation across participating villages, supported village land use planning, and focused on strengthening women’s land rights. The activity helped demarcate more than 70,000 land parcels and register more than 60,000 CCROs using USAID’s digital Mobile Application to Secure Tenure (MAST) technology.

Evaluation Design

USAID, through its E3 Analytics and Evaluation Project, supported the design and implementation of a cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) impact evaluation of LTA. The evaluation team worked with LTA and Iringa District authorities to randomly assign villages to receive the LTA activity (30 villages) or serve as a control group (30 villages). The evaluation collected data via a panel survey of 1,361 households across both LTA and control villages, interviewing the head of household and primary female spouse in each household. The first round of data collection took place right before LTA began implementation in 2017. Endline data collection took place in February 2020, around 18 months after households had received their CCROs with LTA’s support. The evaluation used a two-phase RCT design to rigorously test how LTA’s mobile mapping and facilitation of formalized customary land tenure certification affected household tenure security, land disputes, investment, women’s empowerment, longer-term economic wellbeing, and related land use and management issues in Iringa District.

Key Findings

Tenure Security

-

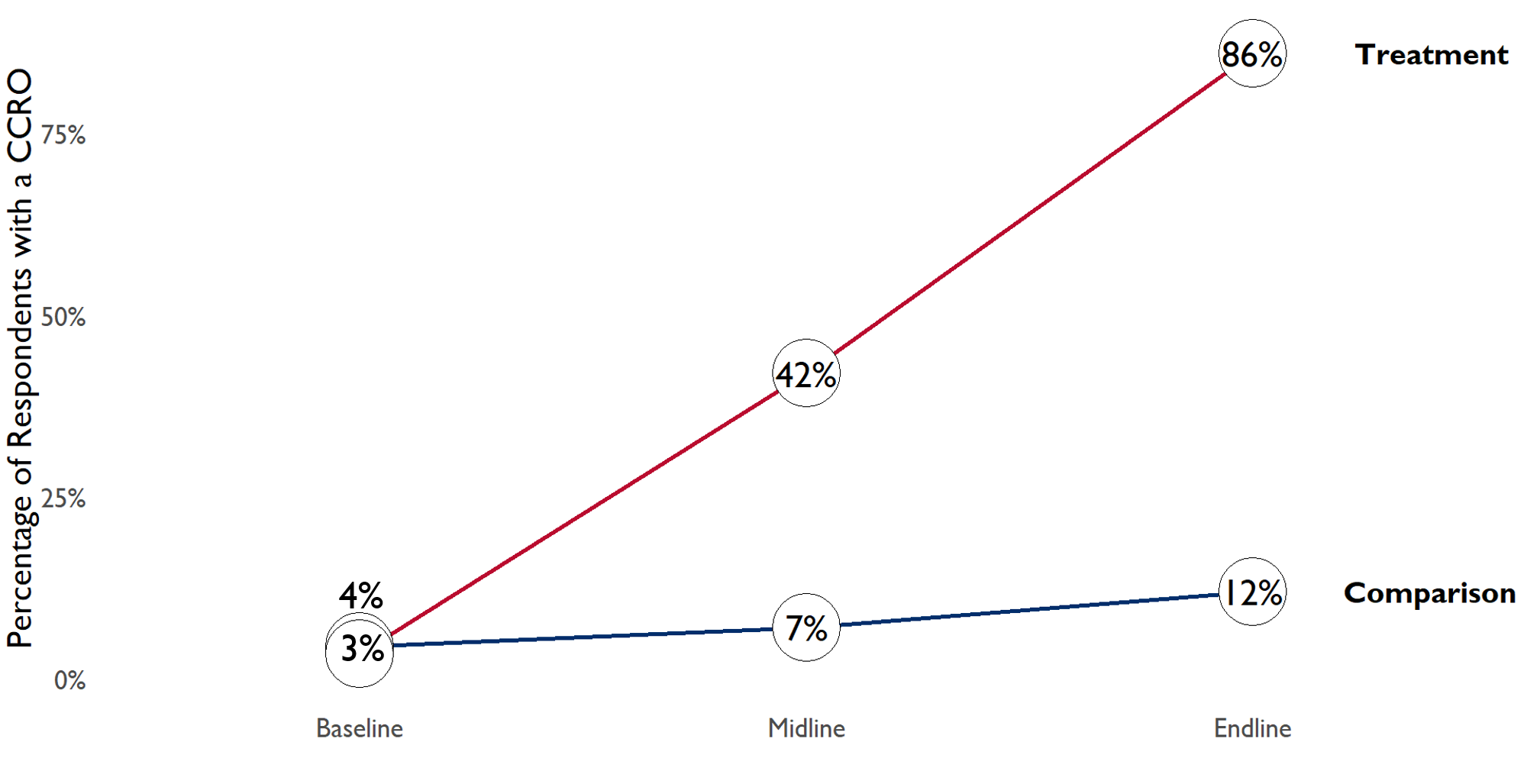

LTA’s facilitation of land mapping and certification increased the percentage of respondents with CCROs. LTA’s systematic village-wide support for CCRO issuance increased the likelihood that a household would have a CCRO by about 100 percent relative to the control group.

- Similar increases in possession of land documentation were observed for male heads, female heads, and female primary spouses. At endline, 83 percent of female primary spouses in LTA villages reported possession of a CCRO, compared to only 13 percent of primary spouses in the control group.

- LTA appears to have positively influenced community concerns about land expropriation, resulting in an 18 percent decrease on average in a household’s probability of expressing concern over land expropriation in their community, controlling for contextual factors.

- LTA led to a 16 percent decrease on average in a household’s probability of feeling tenure insecure, controlling for contextual factors,.

- LTA did not appear to influence perceptions about the risk of losing land that is left fallow.

Land Disputes

- The percentage of households reporting a land dispute fell across both assignment groups, but LTA households experienced a sharper decline.

- LTA households were less concerned on average about future boundary disputes than control households, relative to baseline. LTA activities reduced the probability that respondents felt they could experience a boundary dispute in the next 5 years by 32 percent.

- CCRO documentation via LTA appears to have changed whether and why households think about future dispute risk. By endline, 66 percent of LTA households that were not worried about future boundary disputes said it was because their household had documentation of land rights.

Investments and Land Use

- Land-based investments or productivity-enhancing improvements increased between baseline and endline across both assignment groups. There was no evidence, however, of an increase in land-based investments due to LTA’s CCRO provisioning.

- Impact analysis found a slight increase in household planting of tree crops across both assignment groups, with a larger increase for LTA households (21 to 26 percent).

- Use of communal land increased between baseline and endline across both assignment groups, but the increase was larger for LTA villages (29 percent at baseline to 37 percent at endline).

Empowerment

- LTA’s support led to a large increase in formally documented land rights for women in LTA-supported villages. At endline, 83 percent of female primary spouses in LTA villages reported possession of a CCRO, compared with only 13 percent of primary spouses in the control group. Similarly, 88 percent of female household heads in LTA villages reported having a CCRO compared with 10 percent of female-headed households in the control group.

- There was an increase in male-led decision making in the household during LTA across both assignment groups, but there was no evidence LTA had an effect on this change.

- Women’s participation in food crop farming was high, followed by minor household expenditures, livestock raising, cash crop farming, and major household expenditures.

- A large proportion of female primary spouses typically felt they had at least some input into decision making across the four main productive activities, where they participated in them, and this changed little across survey rounds. There was no evidence LTA had an effect on this.

Economic Outcomes

- There was no evidence of a change in household credit access (stable at around 13 percent for both groups and survey rounds) or amount borrowed (stable at around 200,000 Tanzanian shillings, or $86) as a result of LTA’s activities. Wives’ borrowing also experienced little change, staying at 21 percent for LTA households and 22 percent of control group households for both survey rounds.

- It is likely too soon for LTA’s activities to have influenced households’ agricultural productivity or income to a level that would affect their food security, but there was an increase in food security across households in both assignment groups during LTA.

- LTA has not yet increased the rate of borrowing from formal banks. Neighbors or friends were the largest source of financial borrowing across each survey round and assignment group. Use of CCROs in the borrowing process had occurred by endline but was very uncommon.

Key USAID PROGRAMMING Recommendations

- Consider complementing or synchronizing future CCRO provisioning programs with: (1) targeted agricultural extension and market linkages support to villagers within identified value chains, and (2) financial literacy, financial services, and business development support once the CCROs are obtained.

- Ensure a clear grievance system is in place for villagers and develop a system to track and potentially assist households that may experience de facto land dispossession through the land formalization process.

- Revisit key facilitating conditions in the customary land formalization theory of change and update expectations regarding the time that is likely needed to achieve downstream impacts after improved land access and tenure security have been achieved.

- Consider conducting targeted studies on key linking issues across the land formalization and tenure strengthening theory of change, to enhance learning on how facilitating conditions might help customary landholders better leverage their CCRO for sustainable agricultural and economic gains,

- Consider expanding the scope of future impact evaluations to address questions related to village-level land use planning and governance processes, in addition to household-level effects from CCRO provisioning.

- Continue to prioritize RCT approaches to evidence-based learning on customary land formalization projects, to strengthen the overall knowledge base on how customary land formalization may help improve livelihoods for the rural poor, under what conditions, and in what timeframes.

Photo Caption: The impact evaluation field teams walks toward a village in Iringa District, Tanzania. Photo Credit: Jacob Patterson-Stein, MSI