Summary

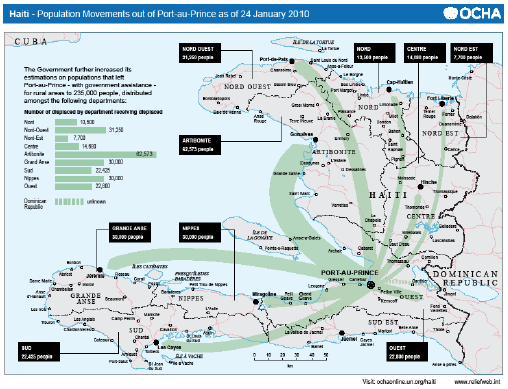

The January 12, 2010, earthquake in Haiti killed an estimated 200,000 people in Port-au-Prince metropolitan area and neighboring zones. As a result of extensive devastation, hundreds of thousands are homeless. The government has announced plans to relocate 400,000 people to camps outside the city. Recent accounts of people fighting over scarce tents and other forms of shelter foreshadows possible conflicts over land that may arise as the focus shifts from immediate emergencies to long-term relief and recovery. Thousands of residents of Port-au-Prince heading for other cities, seeking undeveloped land in rural areas, or returning to land held by relatives, will increase pressure upon and the potential for conflict over land. An Office of Coordination for Humanitarian Assistance (OCHA) situation map for population movement out of Port-au-Prince (January 24, 2010) indicates areas into which large numbers of people are moving (see below).

Land tenure and property rights issues will increasingly come to the fore as the Haitian government and aid organizations attempt to relocate people onto undeveloped land.

Land tenure and property rights issues will increasingly come to the fore as the Haitian government and aid organizations attempt to relocate people onto undeveloped land.

Beyond the immediate acquisition of land for emergency resettlement, the government and donors will need to address land tenure conflict and property rights as large swaths of Port-au-Prince are cleared of rubble and the planning and reconstruction process gets under way and people attempt to return and reclaim their parcels. New and old property claims are up for grabs, land documents related to both urban and rural areas have disappeared under the rubble, and the process of asserting control over land in both earthquake-affected areas and areas into which IDPs are relocating is already underway.

Eyewitness accounts in the week following the earthquake note that occupation of vacated/damaged sites is already occurring. Local levels of government in earthquake affected areas are overwhelmed and poorly funded but have an inherent vested interest in secure tenure arrangements due to grassroots pressures on local elected officials, and due especially to the municipal (commune) levy of taxes on “built properties” through the Contribution Foncière des Propriétés Baties (CFPB). Rural jurisdictions—Conseils d’Administration des Sections Communales (CASEC)—also have a strong vested interest in property, particularly urbanized communal sections on the fringes of Port-au-Prince’s metropolitan communes. Like municipalities, communal sections have the right to census “built” properties for the levy of CFPB property taxes.

The earthquake has given rise to hundreds of thousands of homeless people from poor neighborhoods, including those located in flood plains, and the departure of thousands of urban residents for other areas of Haiti. The sudden arrival of large numbers of Port-au-Prince residents in provincial towns and rural areas may stress local economies and property arrangements. Latent land tenure conflicts hidden from view due to previous out-migration of rural people to the cities and overseas may resurface as urban-dwellers return to the countryside. The damage to buildings in urban areas by the earthquake has created an unprecedented opportunity to relocate urban populations away from risk-prone areas like fault lines and flood plains in the metropolitan area. This process is already underway as the government and disaster response agencies clear land in the area of Croix des Bouquets for tent cities. These tent cities are likely to evolve into long-term housing arrangements for poor families. These trends create opportunity for the assertion of zoned control over lowland flood plains along the coastal littoral and the Cul de Sac plains.

A special focus of interest should be the fragile slopes of Morne l’Hôpital and peri-urban areas along the east- west ridge from Pétionville through Port-au-Prince and Carrefour. The steeply sloped Morne l’Hôpital benefits, at least theoretically, from its special legal status as a “public utility,” a protected area off limits to construction due to the high risk of erosion and its importance as a source of spring-fed water for CAMEP (Centrale Autonome Métropolitaine d’Eau Potable), the public water utility of Port-au-Prince. Legally, all construction on the slopes of Morne l’Hôpital is illegal in the absence of a formal waiver of building restrictions. This special zone is also formally protected by a special planning and enforcement mechanism, OSAMH, an agency linked to the Ministry of Interior. OSAMH has been active pre-earthquake and worked closely with USAID-funded initiatives to protect the slopes of Morne l’Hôpital, and is an essential stakeholder and partner for initial rapid assessment of property and current post-earthquake efforts to build houses on the slopes of Morne l’Hôpital. The post- earthquake period provides an unprecedented opportunity to assert control over Morne l’Hôpital as a legally protected zone and prevent new housing construction on fragile slopes essential to flood control and the metropolitan water supply.

Haiti does not have an effective national cadastre and lacks a comprehensive, functional system for recording land ownership. Prior to the earthquake, customary arrangements and knowledge characterized the tenure of Haiti with only 40% of landowners possessing documentation such as a legal title or transaction receipt. Registration was more common in Port-au-Prince and other rural areas. Some areas of highly productive land, such as the irrigated zones of the Artibonite Valley and Gonaives Plains, created local cadastres, but they have not been maintained and records are not current.4 In Haiti, the Direction Generale des Impôts (DGI) has been responsible for maintaining and updating registration records. However, the veracity and accuracy of land records is suspect, and there is widespread distrust of government institutions, including those responsible for documenting, maintaining, and upholding land claims. The current status of documents related to land ownership is unknown. However, the DGI building has been severely damaged, and the current status of land records or efforts to secure them is unknown. Many advocate as a priority the recovery and protection of land records held at the DGI.

Post-Earthquake Recovery, Land Tenure and Property Rights

A number of issues related to land and other property are already evident, particularly in Port-au-Prince. Massive numbers of people have moved or are being resettled to undeveloped land. The status of prior claims on these lands is not always clear. Temporary homes are springing up amidst the debris of destroyed buildings; it is unclear whether these new structures belong to the original claimants of the land or have been built by new occupants. The massive demolition and removal of debris and recoverable materials also raises the question of ownership claims over the rubble. The potential re-use and resale value of materials (i.e., sheet metal, iron, wood, usable bricks) is likely to be enormous; how will claims to such materials be managed and by whom?

Coordinated, long-term recovery and rebuilding will require planning and land use zoning. A long history of poorly regulated urban construction contributed heavily to earthquake damages. Efforts to rebuild Port-au-Prince will require an adequate system of building codes, urban planning, and enforcement mechanisms for land-use and construction standards including zoned restrictions on multi-story buildings. Long-term resettlement may entail expropriation of land by government. Best practices for zoning, land-use, and expropriation will require due process, public education, and extensive consultation to ensure that people know their rights and are informed of actions that could affect their claims and use of lands.

Zoning and the property census (recensement général des propriétés baties) undertaken by local governments, property tax collection (CFPB), and the issue of construction permits are legal points of entry for post-earthquake assessments, urban planning, and rebuilding. Secondly, property tax rolls and construction permits are high-value databases that should be rapidly identified, inventoried, and immediately protected. Additionally, early assessment should also identify and inventory the condition of notary data: how many notaries are there in affected areas, where are they now, and can their data be located and secured? Lastly, municipal administrations also manage state lands leased to private citizens (domaine privé de l’état) within municipal jurisdictions, although the central government DGI tax office retains overall authority for such leaseholds. Therefore, both DGI and municipal records of these leased state lands should also be identified, assessed, and secured.

In the aftermath of the 2005 earthquake in South Asia, buildings that were only partially destroyed were used by their owners as evidence of their claims to the underlying land. It may be that some people will resist the full demolition of their homes if it erases the only tangible evidence of their claim to the land, particularly in view of the historical importance in Haiti of physical presence as a basis for asserting claims to land ownership.

The earthquake debris includes staggering amount of materials that can be used for reconstruction, including cinder blocks, wood, steel bars, piping, and wiring. Such movable material presumably belongs to the owner of the damaged buildings, and any attempt to remove such material without the owner’s permission will undoubtedly be construed as “looting.” In many cases, ownership of the rubble will be extremely difficult to establish due to the massive amounts of such material to be removed in this densely settled urban environment. Therefore, clearly defined rules for the management and disposal of these materials need to be created, publicized, and enforced.

The return of urban people to the countryside may lead to severe land conflicts. Urban returnees will seek land from relatives to settle and farm. As much rural land is owned by those who migrated to cities and the United States, the sudden return of urban dwellers will exacerbate an already complex land tenure situation. Latent tenure conflicts related to contentious inheritance claims may suddenly resurface as prime lands become at once more valuable but also more scarce. As in urban municipalities, the earthquake crisis may open up an opportunity to respond actively to the land tenure ambiguities of rural areas.

Provision of loans to individuals will be essential for reconstruction. However, high interest rates (approximately 33%) and the widespread lack of documentation for proof of ownership may limit the willingness of banks to provide credit and people’s ability to acquire it. Given the limited extent of formal titling and concerns regarding the accuracy of existing records, those without formal documentation risk loss of their land or property. Government and aid organizations may not readily extend loans and other reconstruction assistance to those unable to document their claims, further marginalizing those informal settlements or claiming land under customary arrangements. Relief organizations, donors, and the government should establish a plan and procedures for documenting, registering, and adjudicating both formal and informal property claims. This will provide the basis for compensation and reconstruction aid. Community legal assistance will be an important service to guide people through any claims process. The return of urban people to the countryside presently underway increases pressures on rural land use and may generate severe land conflicts. Urban returnees will seek land from relatives for house construction and agricultural use. There will also be intense pressures on absentee landholdings, including land owned by those who have emigrated to urban areas and abroad. Latent tenure conflicts related to competing inheritance claims will undoubtedly resurface as prime lands become at once more valuable but also more scarce. As in urban municipalities, the earthquake crisis may require rapid response to increased land tenure conflict in Haiti’s smaller cities and rural areas.

Public awareness and education through media will be essential for helping people defend their existing legal rights related to land and property. A Port-au-Prince radio station, Signal FM, is raising the property security issue. During a recent airing, a local expert on land insisted on the need for the DGI to protect records of notaries and noted the legal requirement for a judge and lawyer to give prior approval for all building demolitions. Post-conflict and post-disaster recovery efforts in other regions have demonstrated the importance of considering land tenure and property rights issues during recovery and rebuilding. The availability of land for shelter, infrastructure, economic use, and institutions of governance are critical to all and affect the outcome of relief and recovery efforts. Governments and organizations engaged in recovery need to consider key land issues such as rights and access to land, land-use planning, land administration and governance, and land acquisition. Failure to consider these issues in long-term recovery efforts risks further dispossession of vulnerable groups, conflicts over contested land claims, and concentration of land in the hands of those with the ability to take advantage of the disruptive circumstances following a disaster.

International standards for post-disaster recovery include attention to land tenure and property rights issues as a critical element; relief and recovery operations, including assessment; coordination of responses to land issues; incorporation of land issues in strategic planning; and monitoring and evaluation. Draft guidelines developed by UNDP, FAO, and UN-Habitat for post-disaster recovery efforts stress the need for an integration of land tenure and property rights as a key component of all recovery efforts.

In principle, the massive reconstruction and resettlement required as a result of the earthquake is an opportunity to rebuild Port-au-Prince, incorporating best practices of coordination, planning, public participation, governance, and land-use. However, post-disaster efforts elsewhere have demonstrated that adequate results are extremely difficult to achieve in actual practice. Therefore, post-disaster efforts in Haiti should be realistic, adapted and firmly rooted in knowledge of how the land tenure system operates in Haiti, and pertinent of regulations and tools of governance already available.

Immediate Interventions

- Priority 1: Work with relevant authorities to recover and safeguard land-related documents and materials. Offer assistance to locate, recover, and secure land records. Finance the immediate purchase of containers for the storage of documents and establish safe holding areas. Use digital cameras or scanners (where electricity is available) to create electronic back-ups of archives.

- Priority 2: Bring together notaries, local administrative and judicial authorities, community leaders, and other land specialists in a Land Task Force to develop pragmatic strategies to respond to land issues noted above. Work through the USAID LOKAL project to launch these important steps.

- Priority 3: Implement a media campaign to inform the population that the government will seek to protect and respect property rights in the recovery efforts.

- Priority 4: Mobilize a rapid assessment team focusing on the land tenure and property rights situation and issues. Assess:

- Urban and rural areas and/or populations susceptible to land and property rights fraud, abuse, or marginalization during recovery operations (i.e., informal settlements, areas being cleared, etc.);

- Physical damage to offices and buildings housing relevant land authorities and records; and

- Impact upon and availability of land administration staff. What are the anticipated and essential tasks for land administration personnel? Are sufficient numbers of people available?

- Priority 5: Work with government and aid organizations to plan and manage a land claims registration process. Following the 2004 Asian tsunami, community mapping in Indonesia helped settle post-disaster claims and provide some measure of tenure security for those with land held both formally and informally.

- Priority 6: Provide support for community legal assistance and advocacy related to filing claims to land and other property.

- Priority 7: Identify and map areas of high-risk land use and settlement such as earthquake faults, hillsides, and flood-prone areas. Identify resettlement options to assure safe location of homeless and other vulnerable people. Integrate information into planning for settlement of homeless, but also as a base for longer-term urban recovery through use of master plans (Plan d’Urbanisme) and new zoning/construction regulations.

- Priority 8: Coordinate donor contributions to establish reconstruction funds to provide grants and low- interest loans to those unable to secure financing through usual means and particularly vulnerable groups, such as residents of informal settlements and women.

Medium-Term Interventions

- Priority 1: Support civil society, particularly grassroots organizations. Local grassroots organizations are an important source of information on land ownership and occupancy and can play a neighborhood watch role in relation to land grabs, especially those by outsiders.

- Priority 2: Identify programs to strengthen tenure and land allocation practices in areas of in-migration.

- Priority 3: Provide training and support for methods for resolving overlapping claims.

- Priority 4: Support and monitor programs for compensating relocated people or those from whom land is acquired for resettlement.

- Priority 5: Assess and develop a plan for post-disaster recovery issues and actions related to LTPR and plans for restoring and rebuilding land administration institutions and systems.

- Priority 6: Develop recovery plans for land administration organizations, including staff development and training.

Long-Term Intervention

- Priority 1: Support the establishment of due process, public consultation, and compensation as critical elements of long-term urban and rural land use planning.

- Priority 2: Support programs for the recovery of land institutions, modernization of records, and staff recruitment and training.

- Priority 3: Support legislative and regulatory reforms for effective strengthening of land tenure and property rights in urban and rural areas.