Background

Global climate change threatens to impact the livelihoods of millions of the poorest and most vulnerable populations in profound and unpredictable ways. In addition, society’s responses to mitigate the greenhouse gas emissions leading to climate change may provide opportunities for economic growth for rural populations, or dangers to local livelihoods. This paper focuses on understanding how mitigation efforts based on reducing emissions and increasing sequestration by forests (REDD+) may interact with property rights and, by extension, poverty and economic growth for smallholders.

Efforts to combat climate change through reducing emissions and increasing sequestration by forests (REDD+) will require that governments address land tenure and property rights concerns as a principal component of REDD+ readiness.

Donors and civil society must provide oversight to ensure that REDD+ does not lead to a form of centralized forest governance that excludes stakeholders’ traditional rights.

USAID, other donors and partner countries are taking steps to clarify the central role of tenure in REDD+ governance regimes through the development of analyses and tools and implementation of legislation to secure rights to participate in and benefit from REDD+.

Deforestation is one of the primary contributors to the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, accounting for 12–17 percent of anthropogenic emissions globally and responsible for well over 90 percent of national emissions in many developing countries (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] 2007, van der Werf et al. 2009). Forests play a crucial role in combating climate change by absorbing massive amounts of carbon dioxide from the air and storing more than three-quarters of the planet’s above- and below-ground carbon (IPCC 2007). In recognition of these challenges and the opportunities that addressing global forest loss provides, in December 2010, parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) affirmed that an international mechanism to reduce emissions and increase sequestration by forests (REDD+) will be a central element of the international response to climate change. REDD+ will include a framework for incentivizing a range eligible emission reductions related to reducing deforestation rates and forest use activities. Elements will likely build on the UNFCCC’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) approaches for afforestation and reforestation (A/R). However, in contrast to CDM projects, where private project developers generally implement discrete activities and establish contracts outlining the distribution of credits and subsequent benefits, REDD+ emission reductions under an international system will likely be accounted for at a much larger jurisdictional scale (likely national, and potentially with room for smaller scale “nested” activities). This thus requires national-level ‘Readiness’ action plans and strategies, which USAID is currently contributing to through its Climate Change and Development Strategy 2012-2016 and through the implementation of the 2010 USG REDD+ Strategy.

Although the structure of the international regime for REDD+ is still in flux, international institutions, private investors and national governments have begun laying the groundwork for national-level REDD+ in preparation for a link to international carbon markets, which were valued at $126 billion during their height in 2008 (Capoor and Ambrosi 2009). At present, forest carbon activities make up less than 1 percent of the carbon market, although this is expected to grow substantially as rules on the international REDD+ regime emerges, and as countries implement emission reduction pledges. Investors will seek to capitalize on these climate change mitigation opportunities by financing and trading emission reduction credits to meet voluntary targets or comply with international agreements.

Clarification of land and carbon tenure

The implementation of REDD+ approaches on a large scale will involve enormous tracts of land, typically in grasslands and forest, where the statutory laws and customary norms that define rights in many countries are often poorly defined, weakly enforced, or even contradictory so that the property rights of the individuals or communities who own these assets may be challenged. Clarity of property rights will have a critical influence on the ability of individuals and communities to participate in the decision-making processes that establish rights and responsibilities associated with REDD+ activities and on their ability to benefit from REDD+ activities. Because forest carbon represents an ill-defined and relatively new commodity, national legal frameworks may be required to clarify ability of rights holders to own and benefit from the trade of emission reductions.

Contrasting Impacts of Forest Carbon on Local Rights–Mt. Elgon, Uganda and Humbo, Ethiopia

Most forest mitigation activities to date have been A/R projects at a scale of several hundred to more than fifty thousand hectares (ha). Wide-scale implementation of A/R projects has been limited in part due to concerns over long-term management and insecure land tenure. In 1994, the Dutch non-profit FACE Foundation partnered with the Ugandan Wildlife Authority (UWA) to plant 25,000 ha of trees to generate carbon credits within Mt. Elgon National Park. With the park’s establishment in 1993, almost 6,000 people were evicted. Although the reforestation project followed the evictions, it was partially blamed for incentivizing the UWA to implement further evictions and for continued conflict inside the park. The project has since stopped marketing carbon credits.

In contrast, the Assisted Natural Regeneration Project in Humbo, Ethiopia, has delivered carbon credits through CDM; and securing legal titles has been one of the project’s primary objectives. The project design document notes, “Officials have shown…their readiness to transfer the land rights (through holding certificates) to the communities participating in the project,” and “those who possess community holdings have the right to all products produced from the land…including sequestered carbon.” Given restrictions on land rights in Ethiopia, holding certificates provide individuals the greatest amount of tenure security, allowing leasing and inheritance rights and preventing land takings without compensation. This approach demonstrates a level of due diligence and communication that will facilitate positive local impacts. Evidence on benefits from this project since 2009 has largely been positive and it has delivered verified carbon credits.

In developing countries, the potential increase in land values from payments for carbon storage and uncertainties about who will benefit create the potential for tenure conflict. Families and entire communities have been marginalized from participation and even displaced from their land by more powerful stakeholders, as in the case of the FACE Foundation’s reforestation project in Mt. Elgon National Park, Uganda (Lang and Byakola 2006), early PROFAFOR work in Ecuador (Granda 2005) and the first CDM reforestation project in Pearl River Basin, China (Gong et al 2010). Not all experiences with forest carbon projects have been negative; some have worked to secure tenure by helping to formalize traditional rights, as in World Vision’s Humbo Assisted Natural Regeneration Project on communal land in Ethiopia (see box below), and Wildlife Work’s Kasigau Project in Kenya. As REDD+ becomes a prominent component of the international response to climate change, it is important to learn from existing forest carbon mitigation efforts to ensure that REDD+ acts as a positive force for rural resource governance, does not undermine property rights, and creates economic opportunities for those with legitimate rights to these assets. Experiences with A/R project-level activities, which have been an accepted component of the international mitigation regime through the CDM and are likely to be encompassed within the definition of REDD+, offer a potentially valuable source of empirical data on the relationships among REDD+, tenure, and the livelihoods of rural rights holders.

In recent years, as political interest in REDD+ has grown substantially, so has the recognition that in most countries, successful national-level REDD+ mechanisms will require extensive and well-coordinated institutional preparation and governance reform–including addressing property rights to these assets–referred to as REDD+ readiness. Over $4 billion in international financing was pledged for REDD+ readiness at the national level between 2010 and 2012, the establishment of secure tenure for effective REDD+ implementation has been a top priority, though donors have struggled to define the tenure milestones for REDD+. Donors such as USAID will play an important role in working with host countries to develop and implement REDD+ readiness strategies and ensure that REDD+ related activities protect the rights of local communities and vulnerable populations. This issue brief reviews experiences with existing A/R projects and preparations for REDD+ readiness to examine three areas of interaction between tenure and REDD+ and outlines priorities for safeguarding and enhancing the property rights of local populations, including women and vulnerable groups, in the establishment of an effective REDD+ mechanism.

Land Tenure as the Foundation for REDD+ Success

A number of processes at the international level (including the UNFCCC, the UN-REDD Programme, the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility [FCPF], the Forest Investment Program [FIP], and the REDD+ Partnership) and efforts from the private sector (under the Verified Carbon Standard [VCS] and other standards) are shaping the institutional landscape of rules and governance structures for implementing REDD+. Many of the potential approaches to REDD+ will be based on national- or sub-national/jurisdictional level emissions accounting, whereby monitoring efforts would ensure that isolated projects do not result in “leakage” by simply displacing deforestation pressures to neighboring forests. The Cancun Agreement calls for REDD+ activities to “be implemented in the context of sustainable development and reducing poverty” and for guidance on social and environmental safeguards to be developed, including safeguard information systems, to assure the “full and effective participation of stakeholders” (UNFCCC 2010). It further recognizes the need to take into account both land tenure and gender considerations. These participation and monitoring requirements will place the onus on governments to engage in a REDD+ readiness phase to develop rules and institutions for monitoring compliance and managing or providing some oversight on stakeholder engagement and benefit distribution. Every international REDD+ process acknowledges the importance of clarifying land tenure as a foundation for effective REDD+ institutions and implementation on the ground. However, even in cases where rights are clear, REDD+ activities will create new pressures on land tenure and resource governance with uncertain impacts on a variety of poor and vulnerable groups, including women, who own and use these assets.

Land tenure is characterized by the bundles of rights, rules, and institutions that define individual or community access to land. Critical rights include rights of access, rights of withdrawal of resources, rights of management, rights of exclusion, rights of alienation (to sell property), and authority to sanction (Ostrom and Schlager 1996, USAID 2011). The lack of secure tenure for local populations is recognized as a principal driver of deforestation in many developing countries (Angelsen 2008). Furthermore, in many cases, tenure is customarily or even legally secured through converting forest to agricultural land, which provides perverse incentives for deforestation (Cotula and Mayers 2009). As a result, local communities often have few incentives to enforce forest resource use rules when their own rights are unprotected. Clarification and increased security of rights is therefore widely seen as the first step toward REDD+ readiness. Nevertheless, although most national REDD Preparation Proposals (R-PP) acknowledge this need, few lay out strategies to achieve these goals (Davis et al. 2010).

“There is no reference to these conflicts resulting from the insufficient recognition of indigenous territories and the lack of an adequate land titling policy. The current state of titling enables these territories to be regarded as ‘free areas’ for REDD projects or large‐scale exploitation. The Readiness‐Preparation Proposal (R-PP) not only ignores the weakness of the Peruvian framework with respect to indigenous lands and territories, but also fails to mention that there have been serious problems in its implementation”

(Rainforest Foundation 2010).

Defining stakeholders

Large groups of rural populations, many of which belong to traditionally marginalized stakeholder groups (such as nomadic or pastoral populations, ethnic minorities, and women) will be impacted by forest carbon mitigation activities. Yet the clarification of relevant stakeholders is a particular challenge for forest carbon projects because of overlapping customary rights and large numbers of potential stakeholders. With the focus of REDD+ readiness at the national level, there is a risk that national governments will simplify the consideration of complex local tenure institutions for the sake of expediency. With pressures on national governments to meet REDD+ readiness requirements, there is an incentive to look for shortcuts to ensure that an issue like clarity of property rights does not impede progress toward receiving benefits and fully engage in REDD+. This simplification could be based on fast-tracking tenure clarification processes, overlooking or disregarding complex local customary tenure regimes, or even undermining existing property rights to benefit the elite. Such a process may systematically exclude certain populations, for example, if national governments focus attention on those with title to land and fail to consider the needs and rights of traditional usufruct rights holders, women, and marginalized groups within communities. The failure to consider a wider set of stakeholders has been observed in A/R activities and has led to the loss of rights and subsequent displacement of pastoralists and small farmers–often on land that was legally owned by the government but customarily managed by local populations (Corbera and Brown 2010; USAID 2011).

The systematic marginalization of pastoral and nomadic stakeholders could emerge based on their disproportional use of eligible land for forest carbon mitigation (e.g., abandoned, degraded, or unmanaged grassland under A/R methodologies or forested land in other REDD+ projects). Degraded grassland and natural forests conjure images of underused resources, but these do not reflect latent rights on these lands for use as seasonal pastures, long-term agricultural fallows, or resources upon which to draw in difficult years (Unruh 2008). As often observed in cases where project design documents (PDDs) for A/R projects downplay or disregard impacts on grazing rights, there is the risk of excluding stakeholders and decreased intervention effectiveness. In Ecuador’s PROFAFOR reforestation projects, failure to consult with pastoralists adequately and consider customary rights has been a primary cause of tree mortality. Limits on grazing have forced families to reduce herd sizes, place more livestock on smaller remaining pastures, and/or purchase or rent grazing rights on new lands–each of which has led to negative livelihood impacts (Granda 2005). These new pressures could also lead to leakage in the event that pastoralists decide to clear new land to make up for this lost use of pastures. Furthermore, the participation of women in formal resource management decisions has been limited in many cases, leading to inadequate recognition of the needs and management responsibilities of women in a variety of forest-use activities, increased attention must be paid to include all local stakeholders in REDD+ readiness, particularly those without legal title to land.

Defining rights

REDD+ readiness and implementation and existing A/R activities often operate in national and local contexts with unclear and overlapping customary and statutory rights. Carbon mitigation projects not only place pressure on these existing rights but also create new rights that must be clarified. Women and other vulnerable populations are particularly at risk of being excluded from participating in decisions and accessing new rights unless explicit efforts are undertaken to secure their role in forest carbon regimes. Two of the most controversial rights (though by no means the only) that emerge from these activities are the right to benefit from carbon transactions and the right to full and effective participation in forest carbon mitigation activities.

The USAID Issue Brief on Climate Change, Property Rights, and Resource Governance outlines five key intersections between property rights and climate change that are equally relevant for REDD+:

- Dramatic changes in land and natural resource-based asset value;

- Displacement and migration of people;

- Further marginalization of the disenfranchised;

- Transformation of resource management; and

- Challenges in the distribution of carbon benefits.

(See Issues Briefs, http://usaidlandtenure.net.)

Right to benefit from carbon transactions. Carbon is a new commodity, and the relationship between land ownership and carbon ownership (and/or the right to benefit from selling it) is unclear in many countries. Levels of recognition of this right vary greatly among countries in the short time since carbon benefits have existed. In A/R projects, ownership of carbon and the distribution of benefits associated with selling carbon credits are typically written into contracts and are based on national laws and negotiations among government, landowners, and project developers with some consideration of others impacted by the project (Baker and McKenzie 2010). In the case of the Green Resources Uchindile Reforestation Project in Tanzania, a percentage of benefits from carbon sales is allocated to local communities, although the majority rests with the project developer (Green Resources 2009). In Papua New Guinea, lawyers have contested attempts by project developers to engage with local communities in an avoided deforestation project, noting that despite indigenous populations’ ownership of the forest, “carbon is an intangible asset not contemplated by any custom…and there is no custom for dealing with such a right” (O’Briens 2010). Other countries are beginning to consider how the distribution of various property rights will be associated with carbon benefits. Brazil, for example, has legislated that logging concessions do not transfer carbon rights to timber operators. Costa Rica claims that existing laws and experience with payments for ecosystem services create precedence for allocating carbon rights based on land ownership (Costa Rica R-PP 2010). However, in many African and Asian countries where land is under state ownership but is managed de facto by local communities, land ownership as the sole basis for awarding carbon rights will not be practical.

Even if carbon rights are well-defined legally and distributed equitably among legitimate stakeholders, there are concerns that poorly informed rights holders will be targeted to sell their carbon rights to outside speculators, without fully understanding the coinciding obligations or the value of the transaction. Criticism has been leveled at cases where “(rural) landowners…think they’re setting up a deal to suck oxygen from the trees to create a big tank in the west” (Sydney Morning Herald 2009). Alternatively, land owners may be willing to sell their land outright to private speculators, as occurred in Costa Rica following the implementation of its payment for environmental services law in the 1990s (Takacs 2009). While this has not been observed to date for REDD+ or A/R projects, it has become a common practice related to biofuels speculation in a number of developing countries. Such purchases of private land to speculators for carbon interventions may ultimately allow the new owners the right to exclude others and limit traditional use rights. Alternatively, if such arrangements occur through a process that permits traditional use rights and recognizes fair benefit distribution practices, they may strengthen economic opportunities for rural stakeholders.

For REDD+ to take off, there is a need for clarification on what groups have the right to access benefits from carbon, and how rights can be transferred. REDD+ readiness Proposal Idea Notes and R-PPs have been criticized for inadequately elaborating approaches to defining carbon rights. Davis et al. (2009) note that “few countries address the need to clarify carbon rights within existing tenure systems. Given the strong consensus amongst participating countries that improving tenure security is critical for REDD+, a deeper and more practical discussion of how these issues may be resolved will be needed.” Given this danger, it is important that clarification of rights occurs through transparent and consultative processes that consider potential impacts on the range of rights holders. While there is limited global experience to date on efforts to define carbon rights through national REDD+ regimes, USAID has applied its significant experience in land tenure and property rights to develop a tool for framing legal rights to carbon benefits generated through REDD+ programming (USAID 2012b), and lessons will be catalogued as the tool is trialed.

Right to full and effective participation. While the prospect of secure tenure rights may help to bring stakeholders to the table and access benefits from REDD+, securing tenure alone will not ensure that stakeholders will be able to participate in decision-making processes. The role of consultation and consent within REDD+, particularly for indigenous populations, has been one of the most controversial topics in the international REDD+ negotiations, with some countries calling for reference to “free, prior, and informed consent,” language from the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Early drafts of decision text on REDD+ under the UNFCCC referenced “free, prior, and informed consultation,” which has been used by the World Bank and supported by the U.S. Government, while other countries have highlighted that there are a variety of approaches to reach the objective of participation, without formally endorsing free, prior, and informed consent under UNDRIP. In the final UNFCCC decision text, compromise was reached with agreement on the need for “full and effective participation,” and additionally noting the adoption of UNDRIP by the UN General Assembly (UNFCCC 2010).

“We cannot wait until all issues related to land tenure, governance, corruption, and the creation of an enabling environment for private sector investment are addressed before we proceed with REDD.”

(Democratic Republic of the Congo response to R-PP review).

Given that REDD+ will likely be coordinated at the national level and rely on both incentives and regulations, there are few inherent assurances for which the views and rights of sub-populations within communities, particularly women, will be accounted. Indeed, there are concerns that national-level responsibility for REDD+ could result in dispossession of populations or unfair responsibilities being placed on particular groups, such as enforcement responsibilities or uncompensated moratoriums against using resources on private property. As a result, there is a need for national REDD+ institutions to prioritize the recognition and clarification of rights to guide the process of realizing full and effective participation. At the international level, guidelines for countries to follow (which ultimately may be incorporated into safeguards) and monitoring capacities should be developed to promote and ensure that populations are consulted and offered the opportunity to engage in decision making as part of wider efforts to improve governance and REDD+ implementation. The ongoing development of guidelines on Safeguard Information Systems is a positive step for avoiding negative outcomes at the national level, and will likely include provisions that help to safeguard the rights of women and vulnerable populations.

Establishing responsibilities

Engaging in forest carbon activities places new voluntary and legislated responsibilities on stakeholders to deliver carbon benefits. Many of these responsibilities will be placed on populations with limited management capacity, and some responsibilities may ultimately undermine tenure security or lead to formal restrictions on customary behavior (Larson and Petkova 2010). In the PROFAFOR reforestation project, Ecuadorian landowners sign a lien on their land as a guarantee that they will meet project commitments. Under this arrangement, participants’ land can be taken if they cannot meet their forest carbon management obligations (Wunder and Alban 2008). These responsibilities place long-term burdens on local populations that may not have full knowledge of the associated risks. In future REDD+ interventions, it is foreseeable that failure to deliver on national REDD+ goals by private landowners could result in government fines or even land takings under the auspices of meeting national targets.

Alternatively, many indigenous groups own considerable territories in the Amazon but have limited management control. In Guarayos, Bolivia, indigenous populations have received title to almost one million hectares of land; given their small population density and lack of support from the state, they have had little success in excluding illegal loggers (Larson et al. 2008). In cases like these, populations with legal tenure may be held responsible for deforestation on lands they possess title to but are not able to effectively manage. For stakeholders to assert control over forests, they need the authority and capacity, as well as institutional support, to sanction those who violate management rules. This highlights the significant capacity building at all levels that is required for stakeholders to actively and effectively manage their lands for forest carbon benefits even after rights and responsibilities are clear. If the institutional structures are not in place to support early efforts by stakeholders to fulfill their responsibilities, REDD+ will not succeed.

Based on the threats associated with identifying stakeholders, clarifying rights and establishing responsibilities, new governance institutions and legal frameworks for carbon rights will need to take into account different tenure regimes to ensure that the process for defining carbon and participation rights or for creating responsibilities do not create new risks that undermine opportunities for economic growth. This underscores the need to tackle these issues in the early stages of REDD+ readiness, and to consider how existing tenure rules may need to be implemented or altered to realize equitable, efficient, and effective forest carbon mitigation.

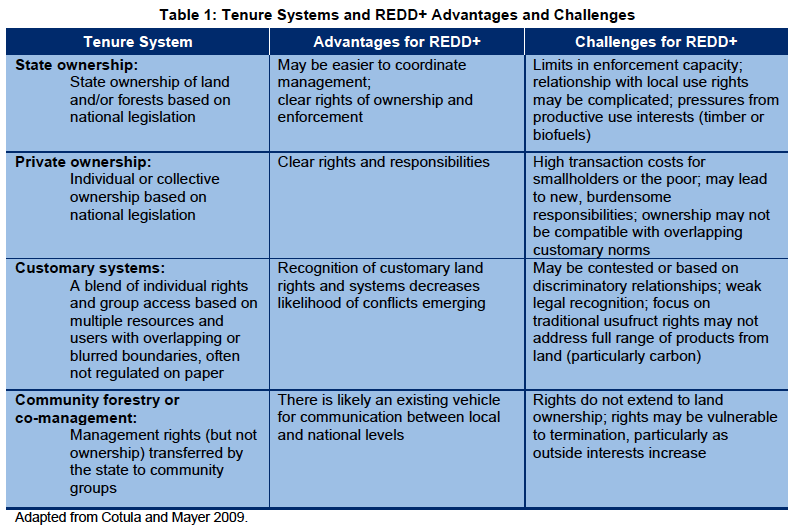

Priorities to Ensure that REDD+ Contributes to Tenure Security

To achieve coordinated REDD+ implementation at the national scale, REDD+ readiness seeks to establish enabling environments, including national legal frameworks; monitoring, reporting, and verification systems; and effective local governance institutions. Readiness and implementation activities will occur within a variety of property rights systems that co-exist and overlap within countries, ranging from state and private ownership to customary land rights and formal co-management. Any governance intervention must be considered based on how it will contribute to REDD+ goals within these different systems (see Table 1, below). In order for investment to flow, property rights must be clear and secure. Security of property rights is one of a number of safeguards providing investors with confidence that investments will result in an economic return. In the absence of these assurances, long-term investment is unlikely to flow into countries, potentially leading to a consolidation of REDD+ activities in the select few countries that have effective institutional enabling environments. This targeted spending would likely exclude some of the most important and threatened forests in the Congo Basin and Southeast Asia, and would result in the failure of REDD+ to achieve its global objectives. Both the USG REDD+ Strategy and the USAID Climate Change and Development Strategy identify tenure reform as a priority area for USG investment to support the implementation of REDD+ governance in partner countries (USAID 2010, USAID 2012).

The need for REDD+ readiness to address insecure tenure should not be construed as a call for states to assert control over forests or as a reason to rush to turn the formal and informal rights of groups into individual rights. Rather, interventions will need to be tailored to address the advantages and challenges facing each respective tenure system. For example, in the case of engaging private smallholders in REDD+, the establishment of collectives may be required to reduce transaction costs through increased participation and scale, as has occurred in other cases through arrangements (such as land trusts). In customary systems, formal institutions may be needed to help map claims to land and resources, recognize and secure customary rights formally, and resolve outstanding disputes. Yet across these varying tenure systems, countries will face common challenges with regard to recognizing traditional use and ownership rights formally, meeting safeguards, and resisting pressures to centralize forest carbon governance.

“REDD+ compensation payments to governments may create a disincentive for forest and conservation and other government authorities to resolve long-standing land disputes in forest areas.”

(Griffiths 2007).

Reconciling forest centralization and decentralization tendencies

There is a likelihood that REDD+ emissions accounting will operate at the national scale and that the large financial incentives associated with meeting targets will lead to pressure for centralization of forest governance and consolidation of power (and incentives) at the national level (Larson and Petkova 2010). This pressure may occur both in countries where there are large private landholders and in countries where state forest control has been decentralized. Central governments may find it simpler and more effective in the short term to implement restrictive laws and increase enforcement to meet national goals than to develop functioning benefit distribution mechanisms and monitoring and compliance institutions at the local and national levels. This stands in direct contrast to international donor efforts over the past decades to decentralize forest governance to regional and local levels. This paradox between the desire to decentralize management to local communities to increase incentives for active local management of forests, and the need to coordinate actions at the national level represents one of the fundamental challenges for REDD+ (Cotula and Mayer 2009). Experiences with past A/R interventions and REDD+ proposals have demonstrated that land conflicts are likely to emerge from interventions that are either completely decentralized or completely centralized, and that for a REDD+ mechanism to function at a national level, there is a need for communication and coordination between national and local stakeholders alongside a transparent benefit distribution mechanism. However, progress on these critical issues is contingent on a clear definition of how existing formal and informal property rights relate to the right to participate in REDD+ decision making and right to benefits.

Key challenges facing REDD+ governance include:

- Monitoring and enforcement;

- Benefit distribution;

- Transparency and accountability;

- Countering drivers of forest loss; and

- General institutional capacity.

Security of land tenure and property rights will influence the ability of REDD+ readiness activities to successfully address each of the above governance concerns.

Local decentralized approaches may avoid central government bureaucracy and corruption, reduce transaction costs, and increase the chance for benefits to accrue at the local level. These approaches are not a panacea; they present their own risks, including corruption and inequitable benefit distribution within communities and between men and women. While working strictly through local institutions may be expedient in the short term, this may lead to the emergence of actions inconsistent with national policies and potential conflicts between government and communities, particularly as national governments attempt to coordinate forest mitigation activities. In the case of the April Salumei Project in Papua New Guinea, project developers attempted to sign contracts with local communities only to find during the comment period that the central government would not recognize carbon rights or allow the project to move forward. Criticisms were subsequently leveled that the proposed project had only consulted a select few communities. In Southern Sudan, Green Resources has planned a REDD+ project on over 150,000 ha of land, including 23,000 ha of commercial reforestation through agreements with a local community, highlighting that “there are virtually no laws, detailed policies, or operational plans governing the forest resources of the region” (Green Resources 2010). While these project areas may face a high risk of forest loss, the lack of tenure security, or assurance of institutional support from government presents an extreme risk for the project’s long-term viability and limits the likelihood that private investors would be interested in financing activities.

A/R and REDD+ initiatives that operate strictly through the central government have often overlooked impacts on local communities. While projects that operate through the national government are likely to work with statutorily secure rights and include enforcement, they may downplay the importance of customary rights that co-exist on state lands, as in the case of many African reforestation projects on national forest land. They may fail to recognize the management role of women in the landscape or inflame historical land conflicts, as in the Kalimantan Forests and Carbon Partnership REDD Initiative in Indonesia where successive national governments have granted overlapping management rights to communities, forest concessionaires, and oil palm plantations over large parcels of land. In this case, the addition of the new REDD+ agenda is unlikely to produce meaningful changes in forest use behavior in the absence of legally recognized property rights, sustained local engagement, and a land dispute resolution mechanism that brings together local regional and national stakeholders (Galudra et al. 2010).

National governments must coordinate REDD+ activities without centralizing forest management. Some national Payments for Environmental Services systems provide a potentially useful framework for creating positive incentives for private landowners and community management units to participate. In Costa Rica, the implementation of Forest Law 7575 made deforestation illegal on private property, but this was accompanied by payments for maintaining forests that have been widely perceived as successful. In this case, the payment system made the restrictive law palatable even if it did not necessarily fully compensate landowners for their lost opportunity costs (Pagiola 2008). Similarly, state payments to local communities with land management rights (ejidos) in Mexico for environmental service provision have acted as strong incentives for improved forest management. These experiences highlight the importance of an effective benefit distribution system to build support for A/R and forest conservation. Approaches that effectively distribute positive incentives alongside new regulatory environments may provide opportunities for successful REDD+ implementation. Nevertheless, it is also clear that from the local to national levels, benefits are prone to elite capture; thus mechanisms for transparency and accountability are necessary, particularly to ensure that women and other groups that are traditionally marginalized do not lose access to benefits.

“[On tenure,] there is very little going in terms of working platforms to build from, and […] REDD opens up opportunities to reinvent DRC’s development path, including options to tackle natural resource governance issues”

(TAP DRC R-PP 2010).

Protecting traditional usufruct rights

Despite the need in many countries for stronger statutory tenure institutions and the formalization of rights, reliance on these solutions alone is not adequate to address the challenges posed by REDD+ implementation. Even when REDD+ creates political will to title land, a focus strictly on clarifying statutory rights to meet REDD+ criteria is likely to miss accounting for the more complex bundle of customary rights that govern land use in practice in many developing countries, particularly if the process is rushed. Unless the tenure clarification process is designed to validate the multiple and overlapping rights to trees, water, pastures, and sub-soils claimed by multiple stakeholders, it will lead to conflict and marginalization of vulnerable stakeholders, and most importantly, strip people of opportunities for economic gain.

The conflicts and contradictions between customary and statutory rights are particularly apparent in the case of A/R projects where a developer is forced to follow statutory laws to the detriment of local populations. Forest carbon interventions introduce enforcement to project sites to ensure that their carbon benefits are realized, but these new enforcement regimes may result in wider socio-economic and tenure impacts. In Uganda’s Kikonda Forest Reserve, a project by Global Woods AG noted 300 individuals collecting charcoal and 100 individuals grazing cattle. Both of these activities are illegal under Ugandan law, which was not being enforced prior to the project. In order to ensure that reforested areas are protected, the company has plans to introduce forest guardians to enforce the reserve boundaries and exclude grazers and charcoal collectors through collaboration with government law enforcement (Global Woods AG 2008). In cases where traditional rights are negatively affected by statutory law, those whose livelihoods have been impacted may have little recourse to express grievances. On the Forest Again Project in Kakamega National Forest, Kenya, grazers were relocated following the implementation of a reforestation project. “Cattle [are grazing] illegally…therefore the relocation exercise may not make provision for compensation” (Rainforest Alliance 2009).

REDD+ activities are likely to encounter these same types of conflicts in the short term, as countries are tempted to enforce existing forest laws or implement new laws that restrict use or access rather than work with customary institutions to tackle the underlying drivers of deforestation. For many countries, protected areas are the backbone of presumed REDD+ activities, and it is likely that governments will be tempted to exclude or evict forest dwellers from these areas. In a number of cases, using protected areas for REDD+ objectives may build on previously contested rights related to the creation of protected areas. Activities focused on forest dwellers could undermine the tenure security of nomadic forest-dwellers in many countries. The Baaka people of the Central African Republic have received recognition of their forest use rights, but they may still be vulnerable to the government’s ability to suspend these rights in the interest of “public utility” (Woodburne and Nelson 2010). Suspension of use rights and evictions has also been observed in the Mau Forest of Kenya, where forest law reform is resulting in the relocation of thousands of forest dependent households. Mixing REDD+ objectives into the implementation of these laws, which often have deeper social and political contexts, can be dangerous for the national and international credibility of REDD+ activities.

Despite the tendency to rely on legal enforcement, many countries acknowledge the opportunity offered by REDD+ to build the political will to address longstanding ambiguities in tenure regimes and have highlighted tenure reform within the package of positive benefits that rural populations will receive from engagement with REDD+. In its R-PP and resulting World Bank review, Ethiopia admits that “customary forest management practices have been eroding in Ethiopia as population and internal migration have increased, and as customary user rights have been replaced by state-sanctioned rights…REDD+ support for policies that formalize the traditional user rights could help preserve and reinvigorate these approaches” (Ethiopia R-PP 2010). In other countries, REDD+ may provide necessary financing to implement existing tenure laws. For example, in Argentina, “many of the public lands are occupied illegally. The occupants may legalize their situation and receive title after staying on the land for a number of years. Unfortunately in many cases, the people don‘t have the money to pay the administrative cost of land regularization” (Argentina R-PP 2010). In this case, REDD+ readiness may be seen as a potential force to finance the formalization of land rights. Indeed, this potentially positive transformational role of addressing REDD+ through tenure reform and tenure reform through REDD+, has been highlighted within the USAID Climate Change and Development Strategy as an example of mainstreaming climate change into development and using climate change programming to advance traditional development goals (USAID 2012a).

A number of A/R projects under the CDM and voluntary markets have demonstrated the capacity for A/R or forest conservation to lead to formalization of customary rights. Under the CDM Reforestation of Croplands and Grasslands in Low Income Communities of Paraguay Project, private project developers assisted local farmers with customary rights to gain certificates of occupancy. The project chose not to assist farmers in gaining full title due to time and administrative constraints. This reflects another challenge in implementing projects within short timelines when a full tenure clarification process could require months or years. In the Ethiopia Humbo Assisted Natural Regeneration Project, World Vision helped seven local communities receive community holding certificates over land for project activities, as well as clarification of their right to carbon, creating a potential precedent for carbon benefits to accompany customary management rights in Ethiopia (World Vision Ethiopia 2009).

While this willingness to help secure tenure should be commended, rushed titling to satisfy validation requirements quickly, as occurred in Paraguay, can cause project developers to overlook complex land use patterns and alienate local populations with traditional usufruct rights. This can lead to new conflicts due to hastily created titles, as has occurred following a recent titling of community lands in Ecuador outside of the forest carbon mitigation framework. In this situation, neighboring communities were forced to create arbitrary boundary lines, despite long-standing shared use of forest between the communities. Alternatively, if management territories for REDD+ are made for communities on a large scale, stakeholders with little relation to one another may be forced to manage a territory jointly, as in Brazil when indigenous groups joined together to create extractive reserves (Cronkleton et al. 2010). Thus, while the clarification of land rights is a central component of REDD+ readiness, it should not be rushed simply to meet REDD+ readiness deadlines. Efforts should be undertaken to ensure that traditional rights are not lost or unduly weakened in the process of defining stakeholders, their rights, and their responsibilities. As statutory institutions emerge through REDD+ readiness, traditional rights should be upheld and formalized, where possible.

Standards as a tool for safeguarding rights in forest carbon projects

The use of standards in the generation of emission reduction credits has been the central approach for ensuring that the rights of project participants are not compromised and that land tenure is clear in forest carbon projects. Many forest carbon activities use standards to provide access to markets through the generation of emission reduction credits, or demonstrate a premium level of social and environmental integrity that provides certainty to investors. Experience with A/R activities under the compliance and voluntary markets has demonstrated that standards can be either a positive or negative force for tenure. There are a wide variety of standards that have emerged for forest mitigation projects, some of which are specific to carbon and generating emission reductions, such as the Verified Carbon Standard and CDM. Others are designed to be complementary standards reflecting best practices or “carbon plus,” such as the Community, Climate, and Biodiversity (CCB) Standards. Still others may reflect standards from outside of carbon mitigation but are relevant to forest management, such as the Forest Stewardship Council certification standards. Each of these standards requires consideration of land tenure in differing degrees.

Certification Standards and Tenure

All carbon offset certification standards require consideration of land tenure, but they vary in their consideration of wider stakeholder impacts. This consideration also varies among different project activities within standard systems. The following presents examples of how tenure is considered under some of the main carbon offset standards related to land use projects:

Clean Development Mechanism: “A description of legal title to the land, rights of access to the sequestered carbon, current land tenure and land use.” http://cdm.unfccc.int

Verified Carbon Standard: “Project participants shall define the project boundary at the beginning of a proposed project activity and shall provide the geographical coordinates of lands to be included…[L]and administration and tenure records (are required).” http://www.v-c-s.org

Climate, Community, and Biodiversity (CCB): “Description of current land use and customary and legal property rights including community property…identifying any ongoing or unresolved conflicts…and describing any disputes over land tenure that were resolved during the last ten years.” http://www.climate-standards.org

Plan Vivo: “Must be secure (land tenure or use rights) so that there can be clear ownership, traceability, and accountability for carbon reduction or sequestration benefits.” http://www.planvivo.org

Standards provide transparency and accountability for activities based on third-party validation and verification. The validation process often raises flags on tenure issues. In the case of Tanzania’s Reforestation in Grasslands of Uchindile Project, “many villagers, as reported in the PDD, feel that Green Resources has broken promises it made when the village decided to cede its customary land to the district council for allotment to Green Resources” (TÜV SÜD 2009). While existing A/R standards and emerging REDD+ standards call for clear land tenure and consideration of stakeholders, there are risks that accompany the use of project standards in A/R and REDD+, particularly the focus on outcomes rather than understanding and resolving ambiguities in tenure regimes. Although facilitating titling of land rights on the part of private project developers is commendable (as on the Paraguay CDM and Ethiopian Humbo projects), most project developers are not tenure professionals, and there is risk that an expedited process of consultation to clarify diverse bundles of rights over land into a single title could create new conflicts over land use and rights, as noted above.

Most certification standards relevant to forest mitigation require documentation of tenure concerns and encourage clarification of the types of existing or potential conflict. For example, planned relocation of activities or compensation of individuals is often cited in project documents, but the process of reaching outcomes is often not elaborated on and proposed solutions do not necessarily represent consensus agreement. An A/R validation audit in Tanzania provided the following response to relocating grazing to areas outside of the A/R project area: “Some cattle owners, however, were not convinced of the proposed relocation interventions such as ‘zero grazing,’ depopulation, and the introduction of high-yield breeds, citing various risk concerns. According to some of the farmers, the high-yield breed needs more care and treatment, which most of them have tried before but lost all of their stock due to their lack of knowledge on how to handle them and the high degree of care needed” (Rainforest Alliance 2008). Some certification standards, such as the CCB and Plan Vivo, require documentation of processes, particularly those concerning stakeholder consultations and conflict resolution, which may lead to a more transparent description of engagement. These standards have varying consideration of benefit distribution or gender considerations and may necessitate using multiple standards to demonstrate achievement of the highest level of social and emission reduction goals.

Thus, while acting as necessary safeguards for stakeholders’ rights, project design documents, and validation and verification reports for certification standards only paint a partial picture of tenure conditions. In order to guard stakeholder’s rights adequately, many of these standards should be modified to require more documentation of process in addition to measuring outcomes to ensure transparency and adherence to best practices. This would represent an increased attention to the social aspects of projects in addition to emissions impacts and would ensure that standards act as a positive force to secure the tenure rights of local populations.

In contrast to standards, which, as noted above, do not tend to outline processes to reach objectives, the use of guidelines may become increasingly important for countries as they try to generate emission reduction credits through national REDD+ systems while demonstrating that they are working to help stakeholders define, extend and exert their rights. The process for developing guidelines on national Safeguard Information Systems under the UNFCCC’s Subsidiary Body on Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) began in June 2011, and is still under development. Some recipient countries have cautioned against making the safeguards into prescriptive eligibility criteria that could limit participation. Instead, they call for general guidelines. The Voluntary Guidelines on Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries, and Forests in the Context of National Food Security of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) are likely to become a useful tool to help countries work through a process to define and strengthen rights. Regardless of the path the SBSTA follows to operationalize safeguards, there is clearly a need for tools and guidelines to help countries reach REDD+ social and environmental objectives. The application of USAID’s Carbon Rights Tool and Tool for Assessment of Benefit Distribution Institutions is a potentially important tool to be trialed and amended based on experience.

Conclusions and Recommendations

As rules governing REDD+ emerge, and as knowledge of country-specific tenure regimes increase, REDD+ institutions and related carbon rights legislation will be tested and evolve. There are three potential outcomes from this process for the future of REDD+:

- Dispossession, loss of rights, and limited participation at the local level. If governments centralize control of forests and decision-making power to meet REDD+ readiness criteria, the involvement of local populations may be limited and REDD+ activities may result in reduced livelihood opportunities (and increased food insecurity). All of this is contradictory to the goals of the international response to climate change.

- Active national and international resistance resulting in failure to lift off. If REDD+ is implemented in the context of insecure tenure, or if new laws negatively impact local populations or sub-populations (leading to the negative outcome noted in 1 above), local, national, and international resistance to REDD+ may grow. This may lead to a loss of political support for the mechanism, a withdrawal of investment, and its subsequent collapse.

- Clarification of tenure and reduced conflict. By addressing tenure head-on, REDD+ has the potential to catalyze policies for the sustainable management of forests internationally.

In practice, these outcomes may naturally occur to varying extents within countries, as governments and civil society attempt to implement nationally appropriate models for readiness. This could lead to some countries developing functioning REDD+ systems, while other countries with low levels of governance trail behind. Still, REDD+ readiness presents a fresh opportunity for countries to address tenure in a way that strengthens the rights of local populations and stimulates long-term investments in the sustainable management of forests. Nevertheless, there is no quick solution to achieve tenure clarity and reduce conflict in REDD+. The long history of tenure reform and the evolution of property rights around the world have revealed the challenges in overcoming corruption and manipulation of administrative mechanisms that benefit a select few. Care must be taken to monitor the implementation and impacts of new rules and institutions and adapt and learn, as needed.

Experiences with A/R activities and REDD+ readiness to date provide valuable lessons reflecting both the risks and opportunities of forest carbon mitigation for tenure security. Developing best practice on definition of stakeholders, their rights and their responsibilities; creation of functional safeguards; securing the resource rights of women; integration of customary and statutory laws; and balance of centralization and decentralization processes will be critical challenges in REDD+ readiness. USAID and the wider donor community have a large role to play in facilitating these changes in resource governance, in part by ascribing to the following recommendations.

Tenure is the central feature of REDD+ readiness

Investment in REDD+ performance in situations where tenure is unclear is a waste of resources. Therefore, further investment in pilot projects or readiness should be contingent on the development and implementation of sound land policies and progress in achieving broader tenure security for affected populations. In most countries, it will not be practical to stall REDD+ investments until tenure concerns are fully addressed. However, efforts need to be made to define and sequence initial tenure priorities and milestones for REDD+ readiness countries, which should be used as benchmarks for subsequent investment in REDD+ readiness and REDD+ pilot work. Mainstreaming tenure and resource governance into national plans is a long-term process that requires patient funding and a willingness to fail and learn from mistakes. There is a need for tenure experts to play a leading role in the ongoing international discussions to develop robust and implementable social standards for REDD+. These experts should also actively engage in developing national readiness strategies.

Political will is a must

Without political will to address land tenure and governance at both the national and local levels, REDD+ will not achieve its full potential. The lack of expansion in the A/R sector in many developing countries is partially attributable to the lack of clear tenure and weak institutions. REDD+ offers a framework and substantial incentives for countries to address tenure and governance concerns. However, if funds are transferred before efforts are made to address tenure and governance concerns, ineffective and corrupt institutions will likely co-opt the REDD+ mechanism and lead to inequitable outcomes.

REDD+ should avoid becoming a mechanism for centralization of forest management

Engagement at the national, regional, and local levels is necessary for A/R activities and absolutely essential for REDD+ interventions. REDD+ readiness should help institutions to coordinate dialogue at multiple scales and build capacity at all levels of society to monitor and enforce compliance and effectively distribute benefits. While central government coordination of activities and some restrictions on behaviors will be required, these should be framed within positive incentives to encourage compliance.

REDD+ readiness requires a clarification and strengthening of rights

Clarification and strengthening of property rights is a crucial component of REDD+ readiness. In particular, this process should document and attempt to reconcile competing resource claims. Greater acknowledgement of the role of customary tenure will be required in the process, and this should be formalized in REDD+ readiness plans and associated legislation. For example, community customary usufruct rights should be protected to ensure that these rights are not impinged upon even if activities occur within protected areas. However, the history over the past decades of attempts to create greater tenure security around the world cautions against facile generalizations. Tenure reforms, such as those suggested here, take time, resources, and political will.

Greater integration of tenure is necessary into carbon offset standards and guidelines and there is a need to focus on both the process and outcome

At present, the validation and verification of projects are overly based on outcomes and do not adequately describe the process, particularly for decisions on who is and is not considered a stakeholder and how decisions are reached. Most project design documents are not adequately transparent in terms of the scope of the community or stakeholder engagement and the subsequent impacts. These highlight a need for modification of standards to require documentation of processes and a greater focus on guidelines that help countries and project developers use best practices to address tenure concerns.

More empirical evidence is needed

Project design documents and validation reports paint a useful but incomplete picture of tenure and mitigation interactions. Their narrow focus often does not provide an adequate breakdown of potential impacts and they reflect a bias toward the interests of the developer who benefits from downplaying potential uncertainties and conflicts over property rights issues. In addition to project documents, there is a need for researchers and tenure specialists to provide more robust narratives on both the opportunities and risks for tenure and property rights associated with REDD+ and A/R interventions, particularly for vulnerable groups such as women and indigenous peoples. As countries develop institutions for REDD+ readiness, it is necessary to share lessons from both success and failures.

It is a primary responsibility of a well-coordinated donor community to ensure that international investments in REDD+ lead to operational safeguards and practices that secure the rights and positively impact the livelihoods of those participating in REDD+. USAID can play an important role in lending its expertise and experience from engaging in land policy and administration programs around the world to help countries meet the challenges posed by REDD+ readiness and create an efficient, equitable, and effective REDD+ mechanism.