“Guaranteeing women’s land and property rights is one of the most powerful but most neglected weapons to stem the feminisation of the HIV and AIDS epidemic.” (ActionAid, 2011)

Summary

Globally, 34 million people were living with HIV at the end of 2011. Sub-Saharan Africa remains most severely affected, with nearly 1 in every 20 adults (4.9 percent) living with HIV and accounting for 69 percent of the people living with HIV worldwide. In South, South-East, and East Asia combined, almost 5 million people are living with HIV. After sub-Saharan Africa, the most heavily affected regions are the Caribbean and Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where 1.0 percent of adults were living with HIV in 2011 (UNAIDS, 2012).

Worldwide, the number of newly infected people continues to fall; the number of people who became infected with HIV in 2011 (2.5 million) was 20 percent lower than in 2001. The sharpest declines in the numbers of people acquiring HIV infection since 2001 have occurred in the Caribbean (42 percent) and sub-Saharan Africa (25 percent). However, since 2001, the number of people newly infected in the Middle East and North Africa has increased by more than 35 percent (from 27,000 to 37,000). The incidence of HIV infection in Eastern Europe and Central Asia began increasing in the late 2000s after having remained relatively stable for several years (ibid).

HIV affects women and girls across all regions. In sub-Saharan Africa, women represent 58 percent of the people living with HIV and bear the greatest burden of care of infected people (ibid). Women’s unequal access to education and employment and their vulnerability to violence compound their greater physiological susceptibility to HIV. Because of social and economic power imbalances between men and women and due to their low status within the household and the community, many women and girls have little capacity to negotiate sex, insist on condom use, or otherwise take steps to protect themselves from HIV (ibid).

Secure rights to land and housing empower women both socially and economically. In Nepal, researchers found that women who own land are significantly “more likely to have the final say” in household decisions (Allendorf, 2007). A study in Brazil indicated that women’s secure land rights are associated with a woman’s increased ability to participate in household decision-making (Mardon, 2005).

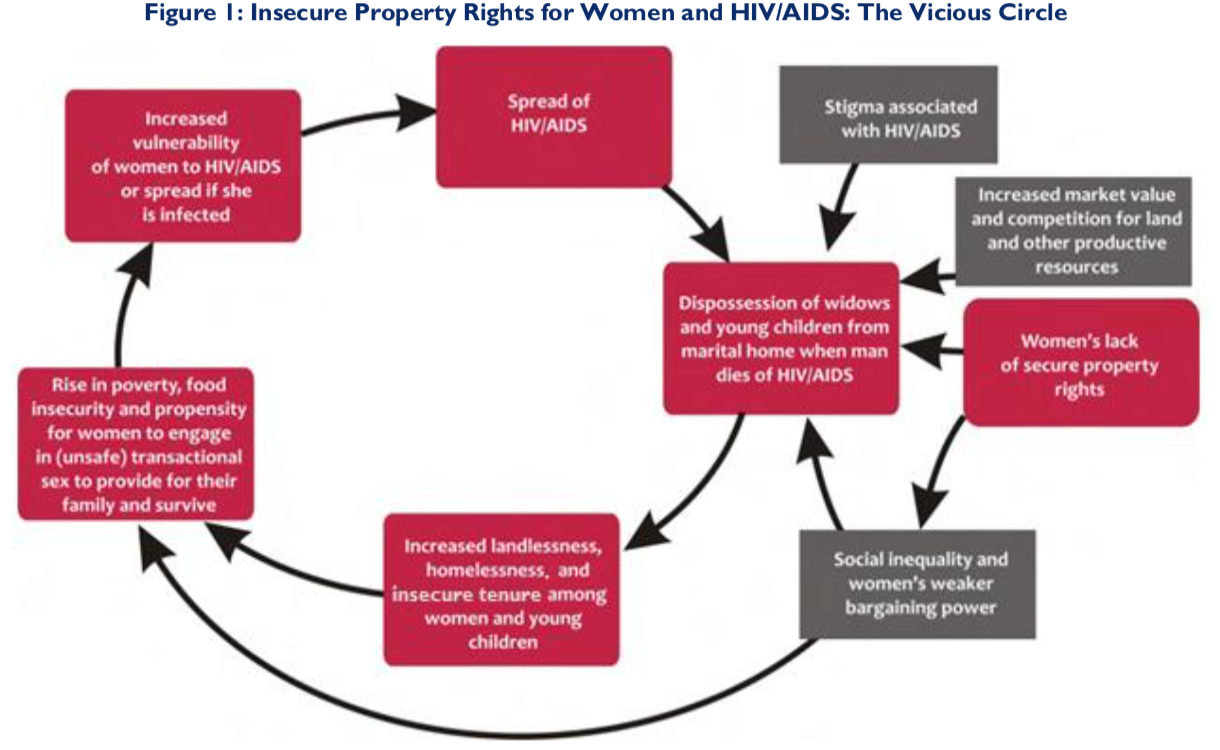

Conversely, insecure land tenure and property rights for women can contribute to the spread of HIV and to a weakened ability to cope with the consequences of AIDS. Land is a critical asset for the rural poor, and in most countries, men hold the rights to and control over land. As a result, women are often economically dependent on men, do not have secure fallback positions, and, therefore, have very little bargaining power.

Household Bargaining Power

Women’s lack of bargaining power in their homes and communities can lead to unsafe sex practices and, therefore, to HIV infection. A study in South Africa indicated that women who were beaten or dominated by their partners were much more likely to become infected with HIV than women who lived in non-violent households. The research was carried out among 1,366 South African women in Soweto and showed that women who were beaten by their husbands or boyfriends were 48 percent more likely to become infected with HIV than those who were not. Those who were emotionally or financially dominated by their partner were 52 percent more likely to be infected than those who were not dominated (UNFPA, citing Dunkle, 2004).

As the primary caretakers of children, women may feel the need to be submissive for the sake of their children’s welfare. A study in Kenya and Zambia found young married women to be even more vulnerable to infection than unmarried women of the same age. This was especially so when they were married to older men, presumably because of their weak bargaining power in those relationships (Glynn et al, 2001).

Studies show that women who have economic independence have higher levels of agency, allowing them to leave a relationship if needed, to make financial decisions that can alleviate or prevent poverty, and to pay for health care and services for themselves and their families (Aidstar, citing Drimie, 2002). This agency is critical to avoid being infected with HIV and to cope with the disease if infection occurs. Examining one area of rural Uganda, a study found that rights to rent out household land enabled women to better cope with the impacts of partner death and HIV/AIDS (ICRW, 2007a).

Women who are asset-deprived with low, unstable incomes or lack of control over their earnings and limited access to their means of production are not in a strong position to bargain for fidelity or safe sex (International Women’s Human Rights Clinic, 2009). With little or no asset cushion, women may find it difficult to exit a relationship with an unfaithful or abusive partner or to refuse marriage to one (ibid).

Agency or status in the home is also key to reducing or eliminating gender-based violence (GBV), which often includes sexual violence, a risk factor for contracting HIV. A review of published data on how economic empowerment affects women’s risk of GBV from 41 locations in 22 countries indicates that ownership of household assets and women’s higher education were generally protective (Aidstar, citing Vyas and Watts, 2008).

Other representative research studies show that:

- Forty-nine percent of women in Kerala, India who did not own immovable property were subjected to physical domestic violence, while only 7 percent of women who owned property experienced violence. Owning property made a bigger difference than employment or education in reducing domestic violence (Panda and Agarwal, 2005).

- Female ownership of property in Northern India “increases a woman’s economic security, reduces her willingness to tolerate violence, and…works toward deterring spousal violence” (Bhattacharya et al, 2009).

- Women in South Asia who are without land and housing face a considerably higher risk of physical and psychological marital violence (ICRW, 2006).

- Women in peri-urban areas of South Africa who are able to acquire their own property are significantly more capable of escaping abuse and partners who refuse to use condoms, thereby lowering their risk of infection (ICRW, 2007a).

While secure property rights alone may not always be sufficient where the threat of violence is severe (ibid), the relationship between women’s bargaining power and GBV is well-established. The relationship between GBV and HIV is also well-established. We also know that rights to land improve women’s economic independence, and thus their bargaining power in the household.

Moreover, for women who have suffered property rights violations, the risk for HIV may be greater due to the lack of personal security from reduced economic support (IFAD, 2011). Women’s weak tenure status, potentially worsened by eviction and resulting landlessness, sets in motion a series of impacts leading to the spread of HIV infection: diminished agricultural production and food security, resorting to transactional sex to cope with resulting poverty, and finally, increased HIV/AIDS infection and spread (see figure below).

HIV/AIDS in Conflict and Post-Conflict

Both UN Security Council Resolutions 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (UNSC, 2000b) and 1308 on HIV and Conflict (UNSC, 2000a) note that women and girls are disproportionately vulnerable to HIV infection during conflict and post-conflict periods. The eastern border of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is thought to be on the verge of a major HIV epidemic. Some 60 percent of the militia who roam the countryside are believed to be HIV-positive, and virtually none of the women have access to services and care (UNFPA, citing Human Rights Watch, 2002). In one survey of 1,125 women widowed and raped during the Rwandan genocide, 70 percent tested positive for HIV (UNFPA, citing avega.org.rw).

During conflict and post-conflict, women face increased responsibility for providing for themselves, their children, and the elderly, but with decreased access to resources. Women and their children typically constitute the majority of displaced persons who are destitute. Women face increased risk of rape, with sexual violence and torture sometimes used as a deliberate tactic by the opposing forces. Victims of rape may face rejection and physical abuse from their own communities (FAO, 2008).

Women’s economic vulnerability may increase significantly during conflict, especially in the case of female-headed households. The research finds that the percentage of female-headed households often increases and that their vulnerability increases because of an increase in dependency rates. The vulnerability of women to poverty is exacerbated by the fact that the jobs available to them are typically low-paid, low-skilled jobs in the form of self- employment in informal activities or unpaid family labor (UN Women, 2012).

The loss of homes, incomes, families, and social support brought on by armed conflicts puts women and girls in positions where they may have to engage in ‘survival sex.’ Women may be forced to exchange sex in order to secure their or their families’ lives and livelihoods, escape to safety, and gain access to food, shelter, or services.

According to Human Rights Watch, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the civil war has created a context in which abusive sexual relationships are more accepted and where many men, both civilians and combatants, regard sex as a service easy to get by using force (WHO, 2004).

Inheritance Rights of Daughters and Widows

As we saw above, land and property rights provide women status and economic power. Land is one of the most critical economic assets for the poor in most developing countries, serving as the main source of production, food security, and social security for many families. While reliable, comparable data is limited in many parts of the world, it is estimated that an increasing proportion of the people living in inadequate housing and homelessness are women and children (United Nations General Assembly, 2009).

Most women depend heavily on men to access economic resources, especially land and housing (COHRE, 2004). For the majority of people in sub-Saharan Africa, access to land is mediated through customary tenure institutions, which typically provide for women to access land through men (ibid). Under most customary systems, a woman upon marriage is expected to move from her father’s land in her natal village to her husband’s village and his family’s land (Rekha, 1995). Because daughters usually leave their parents’ home, women rarely inherit land from their fathers. On the other hand, the primary rights to the land they access when they are married remain in the hands of their husbands. Men decide what land women are given and how much, and oftentimes control the proceeds that women earn from working their land.

For women, gaining rights to land can be difficult. In most parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, inheritance of land is strongly biased in favor of sons (Deere et al, 2003). Even when the law gives daughters the right to inherit, women frequently do not exercise this right because their families have already spent a portion of the family wealth for their marriage and they do not want to take their brother’s share, both from a sense of fairness and because they do not want to spoil the relationship in case they need their brothers’ home as a fallback position (COHRE, 2006).

Some countries have statutory laws that directly discriminate against women’s property inheritance. However, many have “gender neutral” laws that allow discriminatory custom to prevail. For example, laws that stipulate land be bequeathed to a single heir or fail to recognize consensual unions and polygamy often exclude women from inheritance (Knox, Durvey, and Kes, 2007). When land tenure formalization programs are undertaken, they often lead to the head of household (typically the male spouse) being solely named on the title, causing women to lose their rights (World Bank, 2009). Discrimination also occurs in land redistribution programs that favor allocating land to household heads or experienced farmers who, in Asia and Latin America, are primarily men (Deere and Leon, 2001).

Although absence or weakness of rights to land raises all women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS, the situation is often especially dire for widows. There is evidence that risks associated with HIV/AIDS deaths are greatest for widows and their children (IFAD, 2011).

Dispossession of widows from family land is exacerbated by the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS. Widows are frequently blamed for causing the deaths of their husbands. If widows are believed to be infected themselves, their situation can be even worse. A 2006 study on the impact of HIV/AIDS on women and girls in six states in India found that 90 percent of widows interviewed had either been evicted from the marital home or had left under the pressure of stigma; 79 percent reported being denied a share of their husband’s estate. The majority of widows that are HIV positive are young. Nearly 60 percent are less than 30 years of age and another one-third are in the 31 to 40 age group (National AIDS Control Organization, 2006).

Traditionally, when their husbands died, widows in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa were given a life interest in the land, an interest that was often safeguarded by their adult sons who formally inherited the land. However, the rapid spread of HIV/AIDS, especially in Southern and Eastern Africa, has vastly increased the incidence of widowhood and hence the burden of social protection. Moreover, with infection rates and resulting deaths highest among young and middle-aged adults, large numbers of young widows, often with young children, are emerging, creating a further strain on community social protection systems. Research from Zimbabwe and Kenya indicates that their inheritance rights are more likely to be violated than those of older women. This is because women’s ability to hold on to their property after widowhood is dependent on their social networks within the community, which younger women would not have had time to establish. Women’s land rights are also more likely to be violated where widows are childless, since for many women their right to remain on matrimonial property is as mothers of the deceased’s children (ActionAid, 2011). Finally, younger women and orphaned girls are also likely to lose their inheritance rights to brothers or uncles.

Children are often the invisible victims of widow disinheritance. In some cases, the husband’s family will insist on keeping the children, separating them from their mother. More often, when children are young, they are evicted with the mother and cut off from their ancestral land rights. Furthermore, risks to children orphaned by HIV/AIDS are sometimes gender-specific. In Burkina Faso, girl orphans are more likely to suffer from belated schooling in secondary school (Kevane, 2012).

Food Security, Poverty, Migration

While HIV infection is not confined to the poorest, the poor account for most of those infected in Africa (Cohen, n.d.). Poverty is a factor leading to behaviors that expose people to the risk of HIV infection (United Nations, 2005). Research in Botswana and Swaziland found that women who lack sufficient food are 70 percent less likely to perceive personal control in sexual relationships, 50 percent more likely to engage in intergenerational sex, 80 percent more likely to engage in survival sex, and 70 percent more likely to have unprotected sex than women receiving adequate nutrition (Weiser et al, 2007). A study in Mozambique found that women and children who are dispossessed of their property often resort to livelihood strategies that made them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse (Save the Children, 2007).

With rising challenges to carving out sustainable livelihoods in the rural areas, the poor are increasingly migrating in search of work in urban areas or seasonal work on large farms where they are highly vulnerable to engaging in risky sexual behaviors. Landless populations tend to be especially mobile and vulnerable. Where conflict erupts and the poor migrate to Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps or informal settlements, similar conditions are found. Male migrants frequently contract HIV and bring it home, inadvertently infecting their wives or girlfriends. Women who migrate or who are dispossessed of their homes are more vulnerable to engaging in transactional sex as a means of survival (see Collins, Rau, and Rau, 2000 and Krishnan et al, 2008).

Perhaps a more significant and direct impact of secure land rights on the poor who are HIV infected has to do with their ability to cope with HIV once contracted. The poorest by definition are least able to cope with the effects of HIV/AIDS (Cohen, n.d.). The experience of HIV/AIDS can readily lead to an intensification of poverty and can push some non-poor into poverty (United Nations, 2005).

The negative impacts of HIV/AIDS on agricultural production and food security are well documented (Piot et al, 2003). In Africa, women are not only the primary food producers, but also the primary caretakers of the ill. Hence, when they or a member of their family becomes ill, women’s ability to engage in agriculture and other productive activities is reduced and family food security is often compromised. The high cost of HIV/AIDS medication and care also imposes a major financial burden on families, frequently plunging them into debt. A study using data from 1991-2004 in rural Tanzania showed that women whose households suffered from HIV are more economically disadvantaged because their health care costs were higher while the work capacity of household members was reduced (Peterman, 2011). In such situations, insecure rights to land can undermine the ability to cope with the impacts of AIDS.

In some customary systems, people risk losing their land if they are not using it productively, such as when they have an extended illness. In such systems, when the male head of household dies, the risk of land loss heightens and disproportionately affects women because tribal or customary leaders may assume that widows cannot productively use some or all of the land. A study in Northern Zambia found that AIDS-affected agricultural households headed by women own an average of only 1.54 hectares, compared with AIDS-affected households headed by men (3.19 ha) and unaffected households (4.64 ha) (FAO, 2004). Research in Uganda found that, due to constraints on labor, households decreased land cultivation area when a member was affected by HIV. Female-headed households decreased cultivation area by 26 percent compared to an 11 percent reduction for male- headed households. Of the female-headed households, 11 percent of the decrease in land cultivation area was due to distress sale and loss of land to relatives after the death of a spouse (FAO, 2003).

Even if women do not lose land as a consequence of AIDS, discrimination and a lack of resources can constrain access to the inputs necessary to make the land productive. Women are regularly discriminated against when it comes to access to credit, extension, information, networks, and local organizational support. This exclusion is likely to be compounded if they have HIV/AIDS (Strickland, 2004). It is also common for in-laws to rob widows of other productive resources such as livestock or deny them the right to sell it. Together HIV/AIDS and insecure rights to productive assets are contributing to declines in agricultural production, increased food insecurities, and greater feminization of poverty (ibid).

Donor and Research Institution Action

In spite of growing research and policy attention to women’s property rights and to the effects of HIV/AIDS across the continent of Africa, there is still much work to be done (Cooper, 2010). Much of the support for securing women’s property rights with the objective of reducing HIV/AIDS has been invested in documenting the link between secure rights to land for women and a reduction in risky sexual behavior or increase in ability to cope with the disease. USAID, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), the Centre on Housing Rights & Evictions (COHRE), the Chronic Poverty Research Centre (CPRC), and the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) have funded and engaged in this kind of research.

In 2005, a partnership of ICRW, Global Coalition on Women and AIDS, and FAO provided one-year grants to eight local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in sub-Saharan Africa to develop and test approaches for addressing women’s property rights and HIV/AIDS linkages and report on their findings. The projects primarily focused on different types of interventions: public education campaigns about property rights and HIV/AIDS, and paralegal services to women whose husbands died of HIV/AIDS or who were themselves infected. They found that the key social factors that had an influence on whether women are able to realize their property rights were fear of punishment or violence and women’s mistrust of community institutions (Welch, 2007).

While the effects of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa have led to greater attention to inheritance policies in the region (Cooper, n.d.), more investment in monitoring and documenting the impacts of approaches for improving women’s land tenure security is necessary to firmly demonstrate that stronger property rights for women reduces their vulnerability to HIV infection and to reveal which approaches are most effective. At present, there is still limited funding devoted to enhancing women’s economic empowerment as a strategy to combat HIV/AIDS.

USAID property rights work related to HIV/AIDS includes qualitative field interviews with women who are HIV/AIDS victims in Northern Uganda (2007) and in Ethiopia (2008) as part of larger land tenure projects. This field research identified constraints in the women’s ability to access and retain land, and provided recommendations for alleviating those constraints. In September 2008, an assessment of past USAID support for women’s property rights in Kenya and Tanzania confirmed linkages between the disinheritance of widows and AIDS-related deaths.

In 2007, USAID in Zambia funded a survey on the security of women’s access to land in the era of HIV/AIDS. The findings of that quantitative study support the view that HIV/AIDS widows and their dependents face greater livelihood risks (Chapoto, Jayne, and Mason, 2007).

Various U.S. government agencies have begun to address the link between HIV/AIDS and property rights. The U.S. government’s emergency plan for AIDS relief, PEPFAR, mentions in its strategy that gender inequality contributes to the spread of HIV/AIDS (PEPFAR, 2009a). It has also released briefs drawing the link between insecure land rights and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. In 2009, PEPFAR released a brief that stated that unequal land tenure laws may lead to poverty and homelessness among widows, thus increasing their vulnerability to HIV/AIDS (ibid).

In that 2009 brief, PEPFAR committed to “address structural drivers and social determinants of the epidemic.” The PEPFAR strategy also focuses on integrating with other government initiatives (PEPFAR, 2009b). The strategy mentions integrating PEPFAR with Feed the Future, a USAID-led food security initiative which recognizes the link between women’s land rights and food security (PEPFAR, 2009a).

The AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources (AIDSTAR-One) program published a guide linking gender-based violence programs with HIV programs and calling for:

- Situational assessments that review and assess national, provincial, and local plans, laws, policies, and budgetary allocations related to the prevention of and response to GBV, including property and inheritance rights and access to sexual and reproductive health services.

- Addressing GBV within HIV prevention programs by promoting women’s and girls’ economic security through livelihood programs and ensuring their property and inheritance rights.

- Addressing GBV and the prevention of HIV within programs for orphans and other vulnerable children by providing legal services for girls and young women related to property and inheritance rights (Khan, 2011).

USAID’s 2012 gender policy recognizes the gender gaps in both land access/ownership and in HIV/AIDS infection, though it does not explicitly draw a link between the two (USAID, 2012). The U.S. Global Health Initiative identifies “access to land and other productive resources” as the type of program to link with when its partner countries develop health programs (U.S. Global Health Initiative, 2011).

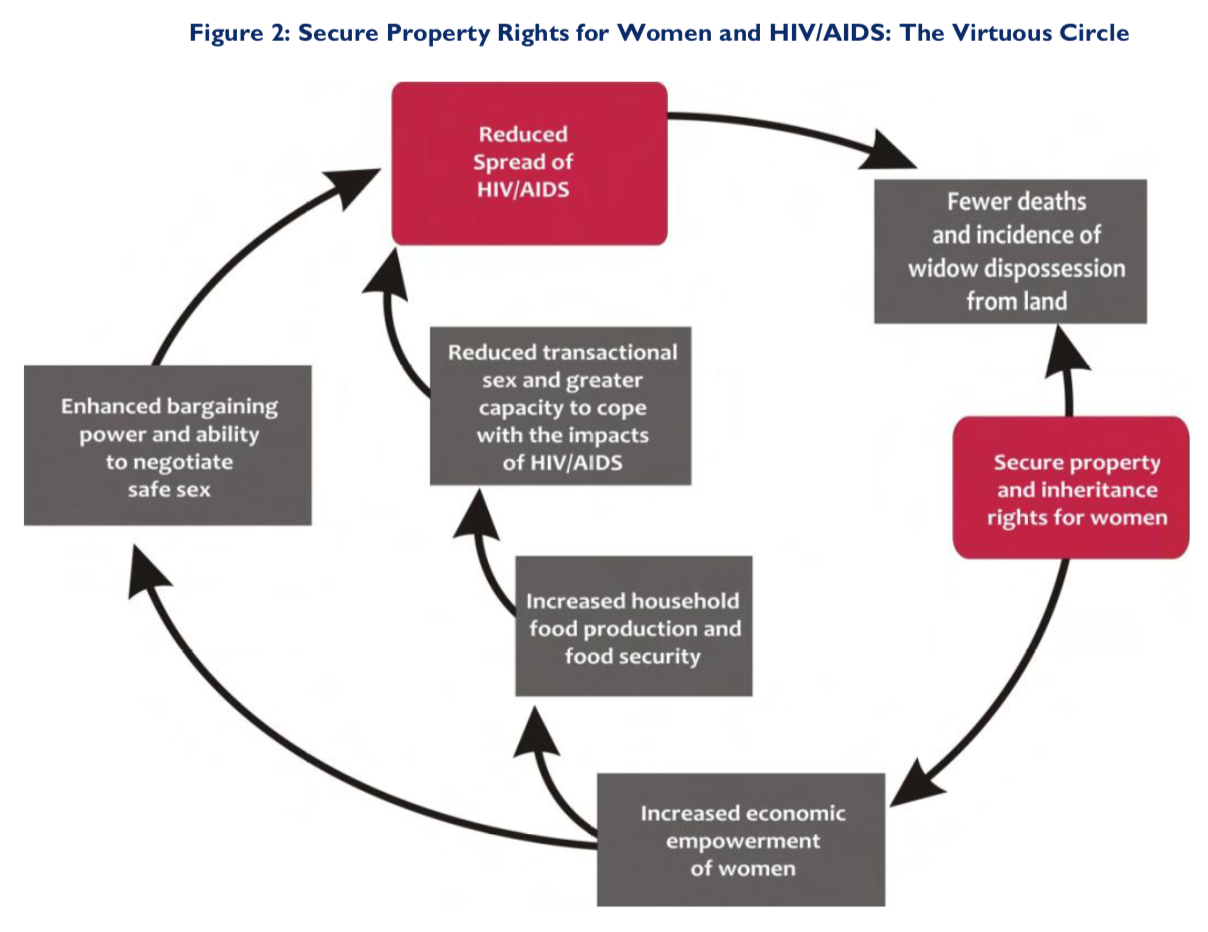

Conclusions and Recommendations for USAID Strategic Intervention

Strengthening women’s property and inheritance rights (WPIRs) offers a unique opportunity to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS as well as enable households to mitigate the negative impacts of HIV/AIDS-related illnesses (ICRW, 2007b).

According to UNAIDS (2003), “Strategies to increase women’s economic independence and legal reforms to recognize women’s property and inheritance rights, should be prioritized by national governments and international donors.” The PEPFAR strategy (PEPFAR, 2009a) includes a focus on women’s specific vulnerabilities, paving the way for U.S. investment to secure one of the most important assets for women in developing countries: land.

Secure land and property rights for women will lead to increased economic empowerment and enhanced bargaining power, which can reduce their risk and vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. For women and families affected by HIV/AIDS, secure land and property rights provides greater capacity to cope with the economic, physical, and emotional shock to the household. An economic safety net is critical to women as caregivers and critical to helping women stave off the poverty and food insecurity that can result from the illness or the illness or death of a spouse.

A number of programming options are relevant for supporting these positive impacts.

- Raise awareness of the links between HIV/AIDS and WPIRs. Women not only need to understand their rights to land but also how to claim and defend those rights through both informal and formal channels. Raising the awareness of men, too—especially local decision-makers—is critical to changing attitudes and even reshaping customary rules.

- Train community members as paralegals to support women in defending their property rights. This includes assisting women to understand their rights, present their cases in local dispute resolution forums, navigate administrative procedures to claim their rights, and access professional legal assistance when necessary.

- Target traditional legal authorities for education and sensitization. As the primary legal forum for many rural women, the support and cooperation of traditional legal authorities can be critical to women’s successful assertion of their rights.

- Provide subsidized legal aid and defense to women to claim their rights. Women whose land rights cannot be secured through local authorities and forums may need to pursue their cases through the courts.

- Educate judges on national and international law on WPIRs and on HIV/AIDS. Such knowledge equips judges to draw on existing jurisprudence to formulate case decisions. Education can be done through judicial seminars as well as production of digests documenting existing case law on WPIRs and on HIV/AIDS.

- Advocate for legal change to make women’s property rights equal to those of men. This includes equal inheritance rights and equal division of matrimonial property in the event of separation or divorce. Lessons from women’s rights organizations in Kenya demonstrate the importance of targeting lawmakers willing to champion reform efforts as well as mobilizing women in rural areas to engage in lobbying efforts. These approaches could be enhanced to include a more explicit focus on HIV/AIDS in the context of WPIRs.

- Document women’s land rights. Where land is redistributed or tenure is formalized, ensure that women are included as joint or co-owners with their husbands or partners. This will strengthen women’s inheritance claims. Women who are single, widows, or HIV-positive should also be prioritized as land recipients in redistribution programs. Innovations are needed to enable documentation of overlapping rights, a key feature of many customary tenure systems.

- Mobilize local women to advocate for and protect their rights. In many rural communities, customary tenure rules and institutions enjoy strong legitimacy but may not be favorable to women. Efforts centered on assisting local women to negotiate with community leaders for stronger recognition and protection of their rights have proven to be effective. Organized groups of women can also help safeguard women’s land rights by watching out for violations, reporting these to authorities, and supporting women to seek redress.

- Set aside land for women and provide them with agricultural financing and extension. Where women have lost land or have limited access, working with governments to purchase or set aside land for women’s ownership or collective access can help them cope with the aftermath of HIV/AIDS as well as stem migration to urban areas where vulnerability to infection and spread is greater. Access to credit and extension is critical to ensuring women have the necessary inputs to make the land they receive productive.

- Address the livelihood needs of HIV/AIDS widows and their children. Support for training and complementary services is crucial for getting women who have been rendered landless back on their feet. This includes training in income-generating and small business management skills; education in nutrition and hygiene that will extend life expectancies; and measures that assist women to access food, credit, low-cost health care, and affordable land and housing for themselves and their families.

- Create opportunities for women to rent land and access labor. Resistance to WPIRs is often rooted in the fear that women will sell land to “outsiders.” Efforts are needed to work with communities to explore alternatives that will enable women to benefit from their land rights without selling and threatening community cohesion. Options for women may include renting out land, hiring in labor, or acquiring land with others to farm as a group.

- Conduct evaluations of HIV/AIDS and land tenure and property rights programming. Understanding the effect of new and innovative interventions will help determine the pathways of influence.