Summary

Pastoralists are agriculturalists who keep domesticated livestock on natural pastures and depend upon their animals as their primary source of income. Supplementary sources of income include agriculture, trade, and handicraft production and, increasingly, salaried income, remittances, and pensions. While virtually all pastoralists exchange livestock products for grain and processed food, pastoral households also provision themselves by directly consuming the milk and meat output of their herds. Ranchers, the common label for pastoralists in industrial countries, routinely have secure title to at least some of the land they use, but many pastoralists in developing countries lack clear property rights because they occupy customary or tribal rangelands that are legally owned by the state, are controlled/owned by the pastoral community itself, or are claimed by other interest groups.

Pastoralists are agriculturalists who keep domesticated livestock on natural pastures and depend upon their animals as their primary source of income. Supplementary sources of income include agriculture, trade, and handicraft production and, increasingly, salaried income, remittances, and pensions. While virtually all pastoralists exchange livestock products for grain and processed food, pastoral households also provision themselves by directly consuming the milk and meat output of their herds. Ranchers, the common label for pastoralists in industrial countries, routinely have secure title to at least some of the land they use, but many pastoralists in developing countries lack clear property rights because they occupy customary or tribal rangelands that are legally owned by the state, are controlled/owned by the pastoral community itself, or are claimed by other interest groups.

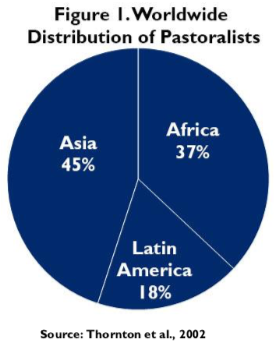

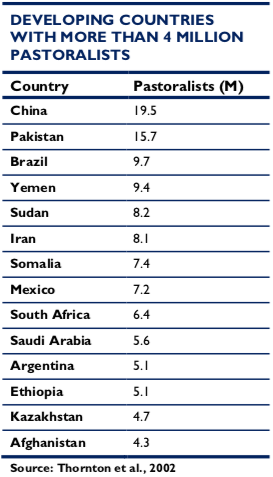

Worldwide there are about 200 million pastoralists, of which 180 million live in developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Central/South America. In terms of absolute numbers, China (at 19.5 million pastoralists) and Pakistan (with 15.7 million) have the largest pastoral populations, but 36 developing countries have more than a million pastoralists. With about three-quarters of their total national population engaged in pastoralism, Mongolia and Somalia are the most predominately pastoral countries on earth (Thornton et al., 2002). Africa is the continent that has the largest land area allocated to pastoral land use—about 40% of land mass—and the largest percentage of the population dedicated to pastoralism. In countries with large pastoralist communities livestock accounts for a significant percentage of the agricultural gross domestic product.

Traditionally, pastoral land rights consisted of access to the key natural resources required to sustain mobile livestock production—pastures, watering points, and the movement corridors that linked together seasonal grazing areas, pastoral settlements or encampments, and markets. For agro-pastoralists engaged in both farming and livestock-keeping, tenure rights also included the ownership of field sites and, in some instances, productive trees such as date palms. These indigenous tenure arrangements routinely mixed elements of common property and exclusive ownership.  A household might have controlled its own agricultural field, while a cluster of related households collectively managed a water point, and a much larger community—a descent group, clan, or entire ethnic group—claimed common rights to pastures. Secondary tenure rights, which allow people to use property belonging to another for specific purposes or limited periods of time, were common and created complex webs of cross-cutting rights and duties among resource users. In these property systems, individuals could have exclusive access to some categories of resources, but they held these rights as members of social groups that were capable of defending the territorial integrity of the entire group, not by virtue of a title deed issued by a government authority. In recent decades, a variety of factors—land conversion, privatization, conflict, population pressure, and the creation of nature reserves, among other trends discussed below—have all led to the erosion of pastoral land rights.

A household might have controlled its own agricultural field, while a cluster of related households collectively managed a water point, and a much larger community—a descent group, clan, or entire ethnic group—claimed common rights to pastures. Secondary tenure rights, which allow people to use property belonging to another for specific purposes or limited periods of time, were common and created complex webs of cross-cutting rights and duties among resource users. In these property systems, individuals could have exclusive access to some categories of resources, but they held these rights as members of social groups that were capable of defending the territorial integrity of the entire group, not by virtue of a title deed issued by a government authority. In recent decades, a variety of factors—land conversion, privatization, conflict, population pressure, and the creation of nature reserves, among other trends discussed below—have all led to the erosion of pastoral land rights.

This briefing paper examines current challenges to pastoral land tenure in developing counties and explores the potential role of USAID in addressing these issues. Policy and programmatic recommendations are consistent with the Voluntary Guidelines for the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries, and Forests (Voluntary Guidelines). The Voluntary Guidelines are an internationally negotiated document of the Committee on World Food Security under the aegis of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 2012).

The Background to Current Challenges

Pastoralists and their property rights have been in retreat for several centuries. An example from the early twentieth century is the “Maasai Moves” of 1904 and 1911, in which the British expropriated more than one-half of the Maasai tribal area, including some of the most productive agricultural land in Kenya, to make way for white settlers (Rutten, 1992). In the 1920s and 1930s, Reza Shah Pahlavi used military force in an attempt to pacify and settle Iran’s pastoralists, with catastrophic loss of human and animal life (Tapper, 2003). In Kazakhstan between 1929 and 1933, the collectivization of land and livestock and nomadic settlement under Stalin killed 92% of the nation’s sheep; over half the households in the country—the vast majority of which were pastoral—simply disappeared (Conquest, 1986; Olcott, 1995).

A “modernizing agenda” justified these policies. Pastoralists typically live in areas that are too cold, high, or dry for crop agriculture. In these climatically unstable and harsh environments, it is often necessary to move herds, both to avoid seasonal extremes of heat, cold, drought, or insect infestation, and to exploit areas of unusually high but temporary resource productivity. In these circumstances, migratory herd movement is an effective husbandry practice, but modernizing urban elites have typically considered the practice to be primitive and an embarrassment, and sought in the name of progress to stamp it out. Political and military considerations reinforced governments’ misgivings about mobility. By the twentieth century, few pastoral societies could still mount an effective military challenge to national or colonial governments, but many pastoralists remained independent-minded, self-organized at the local level, and tax-averse, and were perceived as an affront to a government’s sovereign authority. The fact that many pastoral groups straddle international borders further strains their relationships to governments and fosters the perception that their movements should be controlled.

By the middle of the twentieth century, the modernizing rationale for developing or eradicating pastoralism had acquired additional justifications. In 1968, Garritt Hardin published The Tragedy of the Commons, an exposé of the purported negative environmental implications of common property (Hardin, 1968). Using open rangelands to exemplify the problems of unrestricted access, Hardin argued that privatization of rangelands and individualization of tenure would remove the incentives for over-exploitation inherent in collective ownership and lead to more sustainable land and resource use.

Box A: PARKS, DAMS AND GUNS—PASTORAL TENURE IN THE OMO VALLEY OF SOUTHERN ETHIOPIA

The Omo National Park (established in 1966) and the Mago National Park (established in 1978) have long threatened pastoral tenure in the Omo Valley. Four agro-pastoral tribal groups with a combined population of about 100,000 live in or around the park. Following boundary demarcation in 2005, there was a risk that they would be declared “squatters” and denied further access or be displaced. Under pressure from human rights groups, the contractor (the Netherlands-based African Parks Foundation) pulled out, citing continued human occupation of the park as their reason (Mursi Online, 2007).

A more recent threat to the residents of the Omo Valley is the Gilgel Gibe III hydroelectric dam on the Omo River (which was due to be completed in 2012). Hundreds of thousands of agro-pastoralists downstream from the dam risked losing their periodically inundated fields and pastures when the river’s natural floods began being regulated by the dam. The dam’s environmental impact assessment was completed two years after construction began and was regarded as inadequate (Greste, 2009a).

Conflict over resources—either between pastoralists and the government or between pastoral groups—is also a danger. The Nyangatom pastoralists straddle the border with Sudan. Many younger Nyangatom fought with the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) during the Sudanese civil war, and are well armed, trained, and experienced fighters. Increased insecurity resulting from the dam is not confined to Ethiopia. Because of the reduced flood and river flow in the Omo Valley due to dam construction, heavily armed Dassanetch pastoralists of southern Ethiopia have moved further into Kenya in search of water and pasture and increasingly have come into conflict with Turkana (Greste, 2009b).

Shortly after the publication of this classic paper, the onset of the first Sahelian drought in the early 1970s, documented in pictures of dead cattle and starving people, seemed to confirm Hardin’s predictions. Taken in combination, drought in the Sahel and Hardin’s reasoning called into question the ability of pastoral communities to collectively manage their own land. Authority to control rangeland resources shifted from local pastoral communities to national governments and internationally funded development initiatives. Governments sought to assert administrative control by actively intervening in rangeland use and management. However, most governments lacked the knowledge and necessary resources to manage range and pasturelands. The shift away from local governance in effect turned these areas into an open-access resource, and the conditions of many deteriorated.

In post-colonial Africa, land reform programs to register rangeland as private or group property were exploited by well-connected and literate individuals at the expense of the majority of pastoral land users, which further undermined indigenous collective management institutions (Peters, 1994; Rutten, 1992; Perkins, 1996). However, in terms of land area and the number of people affected, the most significant experiments in officially regulated group tenure were socialist state and collective farms from the 1930s in the USSR and the 1950s in China, most of which no longer exist (Alimaev and Behnke, 2008; Longworth and Williamson, 1993). In East Africa, the most prominent attempt to develop state-regulated collective tenure was the creation of group ranches in Kenya’s Maasailand beginning in the 1960s. The subsequent breakup of the group ranches due to sedentarization, subdivision, and the registration of individual titles began in the 1970s in the better watered and more commercially valuable parts of Maasailand and gradually spread to more remote and arid areas (Rutten, 1992). Pastoralists who feared losing their land to outsiders believed individual titles would provide greater security than did the tenure rights they held in the ranches (Ntiati, 2002).

By 2000, most elements of a pastoral development agenda modeled on Western systems of livestock production and individualized tenure had lost credibility. Scholars from a number of fields helped shift perspectives on the robustness and benefits of community-based resource management generally, and of pastoralism more specifically. The viability of non-exclusive tenure systems (Ostrom, 1990; Platteau, 1996; Lawry, 1990), the role of mobility in preserving high levels of pastoral output (Ellis and Swift, 1988; Behnke and Scoones, 1993; Niamer-Fuller, 1999), and the economic contribution of pastoralism to developing economies (Hesse and MacGregor, 2006; Hatfield and Davies, 2006) were increasingly recognized in development circles. A 2008 report from International Institute for Environment and Development notes: “Extensive research conducted over several decades in arid and semi-arid rangelands has demonstrated that in terms of both protein production per hectare and environmental benefits, pastoral systems are more productive and viable than the ranching and group ranching or sedentary livestock production systems currently promoted by government and other development agents” (Kipuri and Sorensen, 2008). Among national policy makers, these ideas received a polite, if skeptical, hearing.

However, while evidence mounts that pastoralist communities are capable of sustainable resource management and that they contribute in important ways to national economies, policies have not shifted in ways that increase security for these communities. Instead, many pastoralists have continued to experience land loss, physical insecurity, and economic marginalization.

The factors that prevented policy change, despite improved understandings of pastoral tenure systems, are discussed below.

Parks, Pastoralists, and Nature Conservation

The expansion of the area devoted to nature protection took off in the 1970s. By 2005, 11% of the earth’s land area, or 16.8 million km2, had been officially appropriated for conservation (West et al., 2006). The majority of this land is located in the developing world. The bulk of it falls under the stricter categories in the International Union for Conservation of Nature protected area classification system (Dudley, 2008)—land designated for scientific purposes, wilderness protection, national parks, or habitat/species management—and is, as a result, subject to tight restrictions on its use and occupation by local people.

The number of people who have been displaced by the creation of protected areas is disputed by human rights advocates and conservation groups. Irrespective of the past, future levels of displacement may be high. When they lack secure land tenure and property rights, people who covertly occupy or use resources in protected areas face eviction as legislation and enforcement tightens. By some estimates, between 50% and 100% of all of the more strictly protected areas in South America and Asia are currently used or occupied in this way (Brockington et al., 2006).

Protecting land for conservation comes at a cost. Especially in East Africa, pastoralist communities pay a heavy price for wildlife conservation. About 8% of the land area in Kenya, 28% of Tanzania, and 21% of Uganda is devoted to protected areas, most of which were carved out of pastoral land (Boyd et al., 1999). Parks can turn pastoralists into trespassers on their own land (Turton, 2002) and lead to conflict among pastoral groups, between them and agricultural producers, and between pastoralists and the state.

Box B: TREES, GRASS, AND PARK BOUNDARIES—THE AMBOSELI NATIONAL PARK, KENYA

The woodland savannahs of East Africa shift from forests to grassy plains, and back again, over many decades. The destruction and regeneration of grasses and trees interact with the movements and feeding behavior of both elephants and livestock. This cycle has created and maintained a shifting mosaic of trees and grass, such as in the Amboseli area of Kenya, where Maasai pastoralists and their livestock traditionally co-exist with elephants. With the creation of Amboseli National Park, this savannah ecology has been disrupted: elephant populations confined inside the park have denuded it of trees, while outside, the Maasai and their cattle have taken up residence on land that became increasingly bush-encroached (Western and Nightingale, 2006).

But restrictions on using protected areas are not the only cost for local land users. Some of the most photogenic and commercially valuable East African wildlife species are migratory. In addition to restrictions inside the preserves, pastoralists also live with the costs—in terms of human safety, predation on livestock, disease transmission from wildlife, resource competition, and destruction of cultivated areas—of accommodating wildlife when they migrate outside the preserves (Norton-Griffiths and Southey, 1995; Norton-Griffiths, 2007). In recent decades, donor-backed programs have attempted to offset these costs through community-based wildlife management projects that create incentives for local people to conserve wildlife and other resources. In southern Africa some of these programs have worked well and produced positive economic results and good conservation outcomes. In East Africa, on the other hand, there is little evidence that community-based natural resource management programs have broadly benefited pastoral communities, and the consequences are alarming (Thompson and Homewood, 2002; Homewood et al., 2009). For example, since records began in 1977, Kenya has lost 60%–70% of all of its large wildlife, both within and outside protected areas (Norton-Griffiths, 2007). At least in East Africa, it appears that the current system of wildlife conservation invites corruption and imperils the existence of both wildlife and pastoralists.

National parks need not recreate a “pristine” wilderness devoid of human occupation. When the institutional environment in a given location provides local people opportunities to benefit from conservation efforts they can be extremely effective stewards. People have shaped landscapes for millennia and they can contribute to maintaining, not just destroying, ecologies (see Box B). For example, European Union conservation policies subsidize European pastoralists to engage in environmentally beneficial livestock husbandry practices (European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism) and encourage settlement within park boundaries. An experiment in payment for environmental services among Mongolian herders is outlined in Kett (2010), but it is too soon to evaluate the results. In both Scotland and southern Africa, wildlife flourishes under property arrangements that encourage private sector conservation. Private ranchers in southern Africa generally own the wildlife on their land. In the Highlands pastures of Scotland, estate owners hunt the deer on their own estates but also sell the rights to hunt them. Nonetheless, very few pastoralists on common rangeland have comparable property rights to wild animals. Pastoralists and other local people come into conflict with national park managers/officials and conservationists when they are forced to bear the costs of providing conservation, but do not benefit and are not compensated for their real losses.

Insecurity and the Entanglement of Pastoralists in Regional Conflicts

Conflict over resources is a risk in climatically unstable rangeland environments where people and their animals are routinely moving in search of water, forage, and markets. However, since the late 1990s, especially in Africa, it has become clear that the security situation in many pastoral areas is, in fact, deteriorating. An upsurge in violence caused by conflict over increasingly scarce land and water resources has been exacerbated by the ready availability of automatic weapons, often coming from politically unstable areas like Somalia, northern Uganda, and parts of the Sahel. The root causes of increasing resource scarcity—demographic pressure, the conversion of rangeland to other uses, and enclosures—means that less land is available for pastoralist groups. The result is a continuing spiral of increasing resource scarcity, as conflict further diminishes resource availability by creating no-go areas—buffer zones between armed groups where resources might go unused for years and degrade as a result of neglect (McCabe, 2004; Conant, 1982).

Disputes over pastoral land rights can also be exploited by non-pastoralists to obtain support in regional or international conflicts. This linking of local conflicts involving pastoralists to wider political, ideological, or commercial agendas is especially problematic in Central Asia (Pakistan and Afghanistan) and East Africa (Somalia, Sudan, Kenya, and the Ethiopian-Somali borderlands). In Afghanistan, for example, there is longstanding conflict over pasture rights between Pashtun pastoralists who graze the central highlands in summer and resident Hazara communities that live there permanently. The Pashtun-dominated Taliban regime in Kabul supported the grazing rights of Pashtun nomadic groups. This policy has now been reversed, and there is concern that the Taliban are exploiting the resulting tensions to recruit and arm pastoral groups (Robinett et al., 2008; Wiley, 2004). In the Swat district of the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan, nomadic Gujar pastoralists and resident agro-pastoralists have lost their upland grazing rights to absentee landlords and government forestry plantations (Irfanullah, 2002). Radicalized by their eviction, both landless herders and settlers have been a target for recruitment by the Taliban in Pakistan (Giampaoli and Aggarwal, 2010). In Darfur, Sudan, a weak central government has long mobilized armed militias from pastoral tribes as proxies in its fight against rebel/opposition groups with whom they are competing for access to land and other resources (Young, 2012).

Once local disputes are broadened in this way, violence escalates and customary conflict resolution mechanisms are no longer effective (Galaty, 2005; Rettberg, 2010).

Climate Change

Some of the global regions particularly exposed to climate change—West and Southern Africa, inner Asia, and the sub-Arctic—are inhabited by significant pastoral populations. Exposed annually to natural hazards like droughts, blizzards, and disease epidemics, pastoral production systems may be remarkably well-equipped to cope with this increased climatic instability and uncertainty. Whether pastoralists will be able to deploy their technical skills depends, in part, on their ability to obtain access to new grazing areas so that they can track geographically shifting patterns of resource availability.

The protracted series of Sahel droughts that occurred at the end of the twentieth century and the subsequent “regreening” of the Sahel (Olsson et al., 2005; Giannini et al., 2008; Reij et al., 2005) provide a foretaste of how pastoralists might respond to climate change by attempting to adjust their tenure rights. During the decades of drought, Sahelian rainfall/agro-climatic zones shifted southward (Tucker et al., 1991; Tucker and Nicholson, 1998), and so did pastoral production systems. Camel herders, for example, were forced out of their accustomed northern grazing areas on the desert fringe and moved south into regions vacated by cattle pastoralists, who had themselves been forced to move even further south into areas that had once been primarily agricultural. By the 1990s, the pastoral Fulani, with their high-performance breeds of Sahelian cattle, had penetrated the Nigerian rainforest zone to reach the Atlantic coast (Blench, 1994). As guests and ethnic minorities in their new areas, these incoming Fulani had peacefully relocated without having established secure grazing rights. A similar southward shift in the location of pastoral production systems occurred in Darfur, Sudan, at roughly the same time, accompanied in this instance by inter-communal and state-sponsored violence (Young, 2012).

Mobility and relocation accompanied by attempts to access resources in new areas is one of the ways pastoralists respond to changes in climate. As the preceding examples illustrate, these adjustments in access rights can take place peacefully (as in southern Nigeria) or violently (as in Darfur, Sudan). Recommendations for making these adjustments less painful include clarifying and strengthening property rights regimes, including the reconciliation of diverse and conflicting claims and overlapping rights in resources. Another approach would provide for inclusive public participation to “negotiate claims, regulate disputes, and establish new tenure systems” (Freudenberger and Miller, 2010). In the case of the latter strategy, national governments would need to legally empower communities to negotiate new tenure systems and rights among themselves and then respect/enforce the newly created rules.

As a guide to the policy challenges posed by climate change, the international community’s response to decades of drought in the Sahel is also informative. It is now clear that the droughts of the early 1970s were driven by fluctuations in sea surface temperatures and that region-wide desertification caused by pastoral land use mismanagement does not exist in the Sahel (Giannini et al., 2008; Herrmann et al., 2005). However, this reality did not prevent many desertification experts, international agencies, and national governments from blaming local pastoralists and farmers for the misery they were enduring (Otterman, 1974; Charney, 1975; Lamprey, 1983). In a repeat of the desertification debate, overgrazing, rangeland degradation, and inefficient pastoral production practices are seen in some circle as major contributors to livestock-induced climate change (Steinfeld et al., 2006; Steinfeld et al., 2010). As before, these purported pastoral deficiencies are invoked to justify initiatives that address Western environmental anxieties by expanding the regulatory authority of international and national bureaucracies to determine how pastoralists may use their land, i.e., by expropriating not the land itself but control over it.

Land Conversion

Key resources—often relatively small but extremely productive areas that serve as drought or winter refuges for pastoral herds, including water sources—are the core assets that allow mobile pastoralists to exploit wide, erratically productive rangelands. The economic performance of pastoralism, and its capacity to support human populations and ride out droughts or blizzards, depends on continued access to these key assets, especially river valley lands, water points, or sheltered winter camping areas.

Across Africa and Asia, the loss of pastoral access to pockets of highly productive land and the alienation of this land to other uses is a widespread occurrence (Reid et al., 2008; BurnSilver et al., 2008; Behnke, 2008; Salih, 1987). These changes are frequently justified a priori by unrealistic projections of the increased income that will be generated by more intensive systems of land use or by simply ignoring the opportunity costs of excluding pastoral users.

This conversion of pastoral land to other uses is accelerating. The 2008 boom in agricultural commodity prices and subsequent anxieties about world food security sparked a global wave of large-scale agricultural land acquisitions (Braun and Meinzen-Dick, 2009). According to one of the early World Bank reports on the concern:

Compared to an average annual expansion of global agricultural land of less than 4 million hectares before 2008, 45 million hectares worth of large scale farmland deals were announced even before the end of 2009. More than 70% of such demand has been in Africa, and countries such as Ethiopia, Mozambique, and Sudan have transferred millions of hectares to investors in recent years (World Bank, 2010).

This is bad news for pastoralists. Sudan and Ethiopia, cited in the above quotation, have the largest livestock populations in Africa and support, respectively, the largest and the fourth-largest pastoral populations on the continent (Thornton et al., 2002). The World Bank describes unforested, unprotected, and low-density areas as suitable for expanding agricultural production (World Bank, 2010), a description encompassing many pastoral rangelands. A World Bank study (2010) found that planned and current investments were significantly and negatively correlated with the degree of recognition of rural tenure, suggesting that lower recognition of land rights increases a country’s attractiveness for land acquisition. Controlling for other factors, the countries where rural land users have the weakest tenure rights are those that have attracted the most investor interest and projects.

Privatization and Enclosure

Western notions of individualized land tenure are frequently blamed for destroying traditional, communal systems of pastoral land ownership, but this is an oversimplification. Two characteristic features of modern life—commercialization and centralized state administration—have also promoted the long-term decline and fragmentation of collective systems of rangeland use. When pastoral societies lie outside government control, individual pastoralists cannot own land in the sense of holding legal titles. In these stateless/self-governing environments, individuals secure land use rights through their membership in groups that appropriate land jointly in competition with other groups. The sovereignty and survival of these groups substitute for written titles, and possession is established through culturally sanctioned entitlements, political skill, or military prowess rather than administrative and legal authority.

This situation changes when central government authority becomes effective. If administrative control is accompanied by the growth of markets and trade, the increasing economic value of land effect a change in perception whereby individuals increasingly view land not as part of a livelihood system but as a valuable economic commodity that they can now buy, sell, and convert to other uses. Pressures to privatize or enclose rangelands, therefore, may accompany expanding markets and government control (Lesorogol, 2005; Behnke, 2008).

Both ecological and economic disadvantages are associated with this process. The pursuit of farming both by farmers and ex-pastoralists often occurs in situations of tenure ambiguity and is pursued to secure land rights rather than produce agricultural crops. From Africa to inner Asia, the fragmentation of range and forestlands into small, individually owned plots can cause environmental degradation and reduce livestock output (Boone et al., 2005; Sneath, 1998; Xie and Li, 2008). Properties created in this way may also be too small to support their owners, while land consolidation to create larger holdings would cause the dispossession of vulnerable households.

Population Pressure and Land Security

Even as increasing urbanization, demographic pressure, and economic opportunities are depopulating some rural areas of Africa, demand for rural land in other, semi-arid regions of Africa is increasing, forcing both farmers and herders to adjust to a transition from a land-abundant to a land-scarce rural economy (Mortimore, 2003). This process has tended to undermine pastoral land rights.

As farmers in the Sahel intensify their farming systems or acquire their own livestock, nomadic herders have lost secondary property rights such as grazing on the fallow or harvested fields that are used by farmers. The expansion of cultivated area has encroached on livestock trek routes, pastures, and around watering points, exacerbating herder-farmer conflicts. Similarly, in East Africa, population growth in the highlands has contributed to agricultural encroachment into pastoral areas as farmers expand farming on the margins of pastoral lands.

Even if herders lose none of their grazing land, the value that they can extract from their common property rights will diminish as user numbers expand. This process may be occurring in some parts of East Africa with growing pastoral human populations and declining per capita livestock wealth (Sandford, 2006; Moritz et al., 2009). Heavily stocked rangelands and small, individual herd sizes also leave pastoralists increasingly exposed to climatic shocks, with ever-smaller fluctuations in rainfall or temperature capable of causing hardship and further impoverishment. In such a situation, the risk of an economically significant drought or blizzard increases even if meteorological conditions remain unchanged.

Recommendations for Policy Makers/Strategic Interventions

The Voluntary Guidelines (FAO, 2012) provide a new international framework to guide policy and programs to protect and enhance the rights of pastoralist populations to lands long used for social, cultural, spiritual, and economic ends. The guidelines very clearly spell out in Part 3 that “legal recognition and allocation of tenure rights and duties” principles for protecting the rights of indigenous peoples and other communities with customary tenure. As clause 9.5 notes, “Where indigenous peoples and other communities with customary tenure systems have legitimate tenure rights to the ancestral lands on which they live, states should recognize and protect these rights. Indigenous peoples and other communities with customary tenure systems should not be forcibly evicted from such ancestral lands.” Through a clarion call for recognition of rights of indigenous communities like those of pastoralist populations around the world, clause 9.6 notes, “States should consider adapting their policy, legal, and organizational frameworks to recognize tenure systems of indigenous peoples and other communities with customary tenure systems.” With these and other principles of the Voluntary Guidelines in mind:

- Government and donor initiatives to promulgate new, improved tenure regimes for pastoral areas should be viewed with caution. Frequently, policies and programs that promote radical changes in tenure regimes are ideologically motivated, are inappropriate for rangeland environments, and provide an opportunity for local or national elites to grab resources. Any attempt at reform should be based on an understanding of how the current land tenure system actually functions and on an analysis of who would stand to gain or lose from the proposed changes.

- Public policy should support the enactment of land tenure laws that recognize pastoral mobility and protect pastoral access to the natural resources that sustain mobility. In the last decade, a great deal of legal reform on pastoral land rights pastoralism has emerged in West Africa. Much of this reform is positive and may provide a model for other nations. Legal reforms might address issues such as the recognition of existing resource access and sharing arrangements; the recognition and regulation of cross-border livestock movement; and the creation of livestock corridors to support conflict-free movement, crop-livestock integration, and the protection of emergency pastures or water sources. Once appropriate pastoral legislation is in place, support should emphasize putting these laws into practice, something that has not yet happened in West Africa. Donor support for civil society groups that represent pastoral interests is one way to encourage government administrators to implement laws that they would not otherwise enforce.

- Innovative policies are needed to support property arrangements that defuse the unnecessary conflict between pastoral land rights, parks, and wildlife. Pastoralists do not value and preserve wildlife when they cannot profit from doing so, but very few pastoralists on common rangeland have secure property rights to wild animals. Tentative steps toward giving pastoralists more control over wildlife, as in Namibian conservancies, have been enthusiastically received by pastoral communities. Implied here is a shift in conservation policy away from an emphasis on enforcement and regulation toward the development of positive economic incentives built around clear property rights that allow pastoralists to profit from conservation—the harnessing of property rights to conservation objectives.

- In the place of large-scale tenure reform, policy can usefully concentrate on developing procedures for resolving land disputes, on specifying who is entitled to make legal judgments regarding land ownership, how they may legitimately go about doing so, and how these decisions can be enforced. Over time, this “procedural” approach should generate an evolving body of tenure rules that are based on precedent and reflect local conditions (Toulmin and Quan, 2000). Donors should forbear from promoting any particular land tenure regime—private, communal, or public; settled or pastoral—that would favor one or another competing user group. Donors can instead assist local communities and national governments to identify arrangements whereby interested parties can advance their claims to resources, build the capacity of the institutions that are responsible for processing claims, and assist in the development of locally acceptable legal criteria for choosing between competing claims.

Box C: COTTON AND PASTORALISM IN THE AWASH VALLEY OF ETHIOPIA

Beginning in the 1960s, large sections of the Awash Valley in northeastern Ethiopia were converted from natural floodplain grazing into irrigated cotton and sugar plantations. In a severe drought in 1972–1973, between 100,000 and 200,000 Afar pastoralists and approximately three-quarters of all their livestock died, having lost the riverine pastures upon which they depended during droughts and dry seasons.

It could be argued that the expropriation of key pastoral resources was justified in the national interest, but the economic argument for conversion to irrigated cotton is not strong. Cotton production on one state farm in the Awash Valley between 1980 and 1990 averaged losses of -$1,165 per hectare per year. Following privatization between 2004 and 2009, this same farm averaged a net return of $100 per hectare, while a small pastoral cooperative in the same area netted $520 per hectare in 2009. In comparison, seasonally inundated pastures in the middle Awash Valley would have yielded livestock output with an estimated net value of $460–$920 per hectare in 2009.

Even after privatization and with good local management, it would appear that the returns to cotton farming do not consistently match those from pastoral livestock (Behnke and Kerven, 2011).

- Used with caution, participatory land use planning is relevant to pastoral as well as settled areas. In pastoral settings, special care must be taken to include all resource users in planning exercises (GTZ, 2011). Migratory resource users may not be present when planning discussions are held and secondary rights holders are not always members of the local community in pastoral areas. By exploiting the limited knowledge that development agents may have of local affairs, communities can manipulate donor and government programs to exclude their neighbors or competing land users (Sandford, 1983). In pastoral areas in particular, careful consideration must be given to who actually is “the community.”

- Efforts need to be made to address many pastoral needs in the context of regional cooperation because pastoral production zones often cross national borders. In this respect, recent African Union attention to the problems of pastoralists is encouraging (AU, 2010).

- Policy makers can support skills training, enterprise development, and educational opportunities for those “exiting” pastoralism or those who already are pastoral “drop outs.” In comparison to smallholder agriculture, pastoral economies have a limited ability to absorb surplus labor. Pastoralist groups have historically shed people as means for remaining prosperous. Peaceful and voluntary transition from pastoral livelihoods depends upon pastoralists having the education and skills to compete in other sectors and capacity of other sectors to absorb them. Programs of this kind, some of which might be mobile, would help ex-pastoralists relocate, and would alleviate some of the degradation that results when large numbers of former pastoralists congregate in settlements in range areas.

- The international community should continue to document and publicize large-scale land acquisitions affecting pastoralism. While not confined to pastoral areas, the geographical distribution of current large-scale land acquisitions suggests that pastoral land rights in semi-arid Africa are particularly at risk. The correlation between these transfers and weak national property rights systems also suggests official corruption and state involvement. In addition to working with state actors, policy makers should provide support to national civil society groups that document large-scale land investments and subject these transactions to legal and public scrutiny.

- Planners should recognize that large-scale irrigation schemes in pastoral wetlands and riverine areas do not necessarily provide economic benefits that equal or exceed those from pastoral production. Outside developers can make money by simply transferring control of land suitable for irrigated agriculture from local communities to themselves, while claiming that such transfers are in the national interest (see Box C). These claims should be carefully evaluated. Irrigated agriculture is not new in semi-arid Africa and Asia; policy formulation would benefit from a balanced, large-scale evaluation of what irrigation schemes have actually achieved in recent decades, relative to what they promised and to the opportunity costs of excluding pastoral producers.

Conclusion

More than three decades ago, academics, development workers, and scientists convened at a conference in Nairobi to evaluate the likely “future of pastoral peoples.” The conference followed a turbulent decade of drought and dislocation, and many researchers who attended that initial meeting thought that they were witnessing the potential disappearance of a way of life (Galaty et al., 1981). In the intervening decades, several similar stock-taking conferences have been held—most recently in March 2011 on the future of African pastoralism (Future Agricultures Consortium). Contrary to what one might have expected in 1980, these subsequent meetings have chronicled—at least in Africa and parts of Asia—the remarkable resilience, creativity, and increasing sophistication of pastoral societies and of the indigenous civil society and advocacy groups that represent pastoral interests. Within many African pastoral communities, for example, attitudes about educating children have been transformed. From Mongolian cashmere to the cross-border livestock trade in eastern Africa, official recognition of the pastoral contribution to national economies is growing. Pastoralists and their children now hold high positions in government ministries or teach in universities. Even if they do not yet enforce them, West African states have enacted laws that protect pastoral mobility. Despite continuing poverty and pastoral marginality, these are positive developments that could not have been confidently predicted in 1980. Precisely because it can and does change, pastoralism is here to stay.

Loss of pastoralist access to pastures and water are the counterweight to this optimistic picture. The erosion of pastoral resource entitlements was hardly a topic for discussion in the early 1980s, but it is arguably the single most critical impediment to contemporary pastoral development. In western China, for example, enclosure, nomadic settlement, and rangeland clearances are being undertaken on an unprecedented scale by the Chinese government (Zhaoli et al., 2005) to mitigate rangeland degradation that is unproven (Harris, 2010) and may be exacerbated by government policy (Zhishong and Wen, 2008; Xie and Li, 2008). Documented cases of “land grabbing” in pastoral areas of Africa are all too common (Future Agricultures Consortium). Extensive livestock production requires access to natural resources, and it is difficult to see how pastoralism can sustain itself if this requirement is compromised. Despite progress on many other fronts, pastoral land rights are under pressure as never before, and the issues of resource governance discussed in this brief are at the crux of the future of pastoral peoples. While the Voluntary Guidelines can be interpreted as an international mechanism to protect the rights of indigenous peoples and communities long accustomed to accessing and managing lands through customary governance systems, these agreements will only become effective if they lead to the transformation of policies and laws that have long undermined the interests of pastoralist communities.