Introduction

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has designed this pastoralist programming guidance document to provide a practical tool for USAID missions and operating units (OUs) to more effectively engage with pastoralists. This guidance complements and is informed by the USAID Policy on Promoting the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (PRO-IP) and comprises one piece of USAID’s collection of guidance documents on engagement with Indigenous Peoples. This document highlights challenges, lessons learned, and best practices derived from USAID programming involving pastoralists to help operationalize the PRO-IP’s objectives and operating principles. It also aims to ensure USAID OUs appreciate the complexities associated with pastoralists so that they can effectively design activities that engage pastoralists following the guidance provided by the PRO-IP.

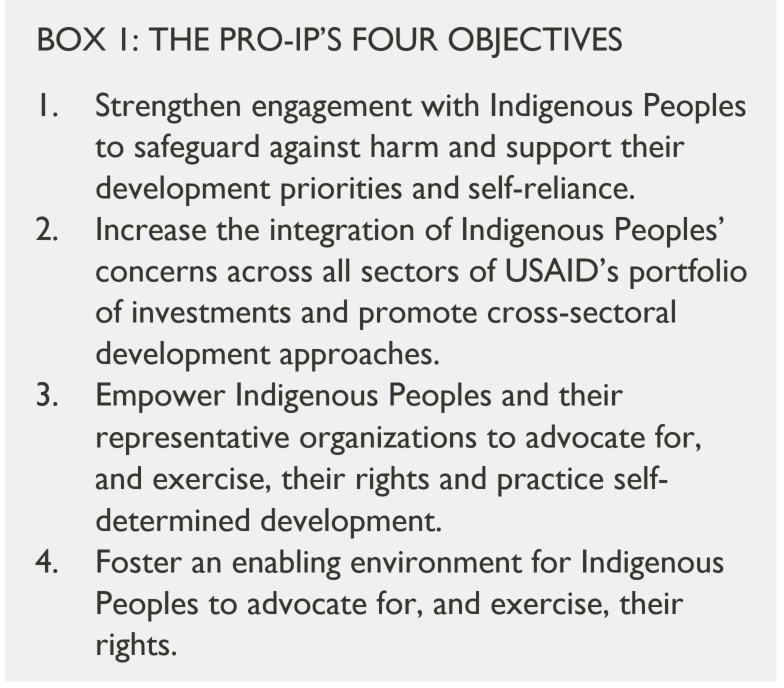

USAID should consider pastoralists’ development priorities and promote their participation in program design and implementation. Engaging pastoralists, understanding their development priorities, and facilitating their participation in all stages of the program cycle through well- structured communication, consultation, and engagement strategies help safeguard against unintended adverse impacts and foster local solutions as envisioned in the Journey to Self-Reliance. Through effective engagement, USAID missions and OUs can develop programs that address various challenges while promoting practices that support pastoralists across different sectors, thus furthering Objective 2 of the PRO-IP (see Box 1). This requires identifying pastoralists in a context-specific manner, engaging them as partners throughout the program cycle, and developing a deeper understanding of pastoralists’ needs, capacities, and interests.

The intersectionality of pastoralists and Indigenous Peoples is complex, context-specific, and sometimes controversial. Studies have examined this intersectionality, noting that pastoralists have longstanding cultures, unique indigenous knowledge, and have faced similar histories and challenges as other Indigenous Peoples, including state policies that contributed to their marginalization, entrenched poverty, discrimination, and human rights violations. Moreover, global alliances, such as the World Alliance of Mobile Indigenous Peoples, as well as international treaties1 and standards highlight other recognized linkages between pastoralists and Indigenous Peoples.

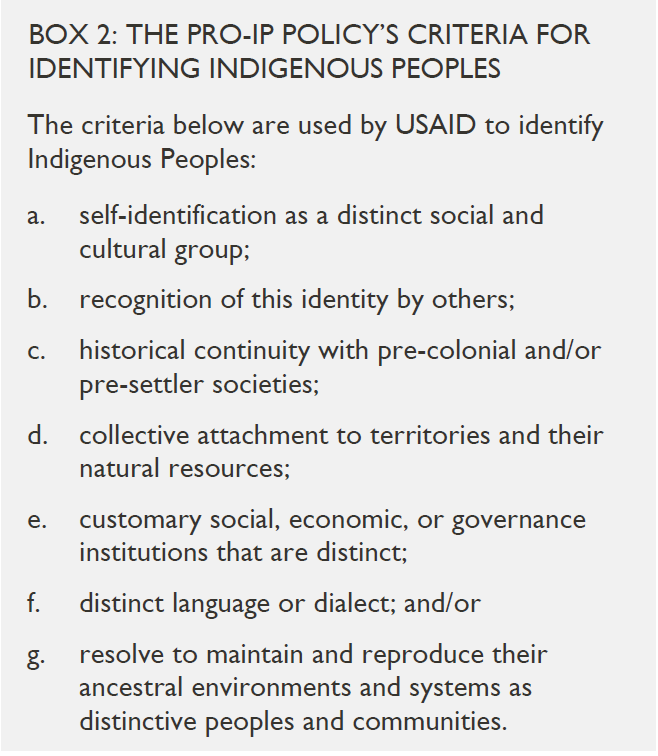

The key challenges, lessons learned, and best practices highlighted in this document help USAID staff more effectively identify groups as both pastoralists and Indigenous Peoples following the PRO-IP. As stated in the PRO-IP, USAID uses a set of criteria rather than a fixed definition to identify Indigenous Peoples (see Box 2). These criteria also draw from those established in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and Performance Standard 7 of the International Financial Corporation (IFC). It is worth emphasizing that not all pastoralists share these characteristics, and not all pastoralists identify as Indigenous Peoples. Based on these criteria, and depending on the geographic location, context, and other factors, some or all of these criteria may apply to pastoralist groups as subsets of Indigenous Peoples for purposes of identification per the PRO-IP.

Although USAID endorses criteria as opposed to a fixed definition, broad conceptual definitions of pastoralism may serve as a helpful starting point in the identification process. While there is no one- size-fits-all definition, FAO, for example, published a technical guide entitled “Improving Governance of Pastoral Lands,” which states that “pastoralism is defined as extensive livestock production in the rangelands and it is practiced worldwide as a response to unique ecological challenges.” FAO further describes how pastoralists’ customary governance institutions, cultural practices, and livelihoods are highly dependent on herd mobility. According to other studies, pastoralism can sometimes be characterized by the degree of movement, from highly nomadic to transhumant to agro-pastoral.2 Although broad definitions must be treated as overly simplistic given the flexible, opportunistic, rapidly changing nature of pastoralists, these conceptual definitions and the guidance presented in this document can be used to develop a general understanding of the concepts and issues, and then determine on a case-by-case basis whether a particular group can be identified as pastoralists and Indigenous Peoples per the PRO-IP criteria shown in Box 2. Given these inherent difficulties associated with identification, it may be helpful to account for other factors relevant to the PRO-IP criteria, including the legal and political context surrounding pastoralist groups, the cultural role that livestock production plays in the livelihoods of pastoralist groups, whether the groups manage resources following customary norms and practices, and whether the groups have a collective attachment to land and resources, among others. More details on the challenges associated with identification are discussed in the Challenges section below.

This guidance document incorporates feedback from interviews with USAID livestock, pastoralism, land governance, and agricultural development specialists, as well as other technical experts with relevant experience and knowledge. This guidance is also based on desktop research of USAID program documents and other relevant sources.

This guidance was prepared by the USAID Integrated Land and Resource Governance project.

[1] In 2007, pastoralist representatives from over 60 countries worldwide signed the Segovia Declaration of Nomadic and Transhumant Pastoralists. This declaration calls on governments and international organizations to “seek prior and informed consent before all private and public initiatives that may affect the integrity of mobile indigenous peoples’ customary territories, resource management systems and nature.”

[2] “Transhumant” has been defined as the regular movement of herds between fixed points (e.g. fixed summer and winter pastures) to exploit seasonal availability of pastures. Agro-pastoralism relates to the practice of agriculture of growing crops and also raising livestock.