Published / Updated: September 2017

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

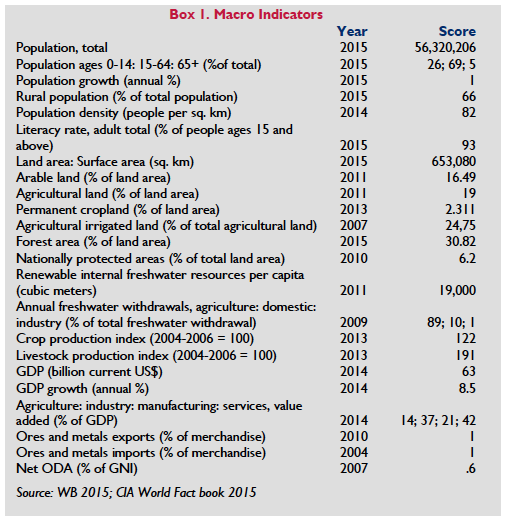

Burma is situated in Southeastern Asia, bordering Bangladesh, India, China, Laos and Thailand. The majority of its population lives in rural areas and depends on land as a primary means of livelihood.

Because all land in Burma ultimately belongs to the state, citizens and organizations depend upon use-rights, but do not own land.

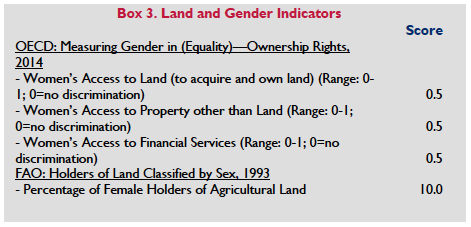

Burma’s laws grant women equal rights in some respects and also recognize certain customary laws that provide women equal rights in relation to land. In practice, however, the rights of many women are governed by customs that do not afford them equal access to or control over land.

Forcible and uncompensated land confiscation is a source of conflict and abuse in Burma, and protests and fear of “land grabs” have escalated as the state opens its markets to foreign investors and pursues policies to dramatically increase industrial agricultural production.

Burma has rich water, forest and mineral resources. However, a rapid expansion of resource extraction efforts in the past three decades has led to widespread land and water pollution, deforestation, community protests and forced relocation.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

To help strengthen the implementation and reform of existing law and build corresponding institutional capacity, USAID and other donors might consider focusing on the following high-impact interventions:

The body of law governing land in Burma is expansive, complex and poorly harmonized, with many of the legal instruments still dating back to the late nineteenth century. Although the state enacted several major land-related laws in 2012, their effect on preexisting laws is unclear. In addition, Burma has adopted a National Land Use Policy (NLUP) covering land use, land tenure and land administration; it is also developing additional policies to meet land-related needs in sectors such as agriculture. Donors should provide well-coordinated technical, legal and other support for the development and implementation of strategically prioritized and sequenced issue specific policies, laws and implementing regulations required to improve land governance, implement the NLUP and eliminate inconsistencies with existing laws and rules.

The new government faces a huge backlog of land-related disputes and grievances, many going back decades. The Government created a Farmlands and Other Lands Acquisition Reexamination Central Committee, along with related subsidiary committees, to address land confiscation and the dispossession of smallholder farmers. Such an effort aligns with the NLUP, which seeks to develop equitable, accessible and transparent mechanisms to resolve such disputes. Donors should provide support to these Committees and other alternative land dispute resolution mechanisms to build capacity and enhance transparency in support of stronger land governance, while simultaneously addressing land tenure issues relating to internally displaced persons and returning refugees in a holistic manner.

Populations relying upon customary tenure arrangements, which the government does not yet legally recognize, as well as smallholder farmers whose land use does not align with how land has been classified or who did not report their land use to the government in the past, are vulnerable to being removed from their land without receiving compensation. Donors should improve tenure security for these populations by supporting the development of: laws and policies that are consistent with the new NLUP and recognize and respect customary tenure systems; and registration schemes that allow for the titling of land under rotational fallow or other customary tenure arrangements.

The land rights held by women in Burma are often highly insecure. Cultural norms and practices often marginalize women within their marriages and households, and many women lack awareness of their rights as joint owners of family land or as family members with rights of inheritance. Rights held by women-headed households are particularly vulnerable to loss to male family members, local elites, and commercial interests. Donors should work with the government to protect and improve women’s land rights through educational programs and legal literacy campaigns focused on increasing women’s knowledge of land rights and land administration procedures. They could also provide support for programs that assist women, their families, and their communities with training in communication and dispute-resolution techniques. Additionally, donors could support the development of legal aid organizations and NGOs, as well as their efforts to expand their services to include a focus on protecting and improving women’s land rights.

Landlessness rates are significant nationally and especially in the Ayeyarwaddy Delta and the Bago Region. Estimates of landlessness among Burma’s rural population range from 30 percent to 50 percent depending on the source of the estimate and the definition of “landless.” Donors should help reduce landlessness by supporting the analysis and development of laws and policies to reduce landlessness and an investigation of whether and in what regions land might be available for allocation to households that possess less than an acre of land.

Burma’s laws permit the state to use compulsory acquisition to acquire land for public purposes and for business purposes. The law defines neither purpose in detail, leaving landholders vulnerable to losing their land through arbitrary processes. Donors should help improve compulsory acquisition processes by providing technical, legal, and policy support for the development of clear procedures and authority that embodies minimum international standards for fair and effective compulsory acquisition procedures consistent with the NLUP.

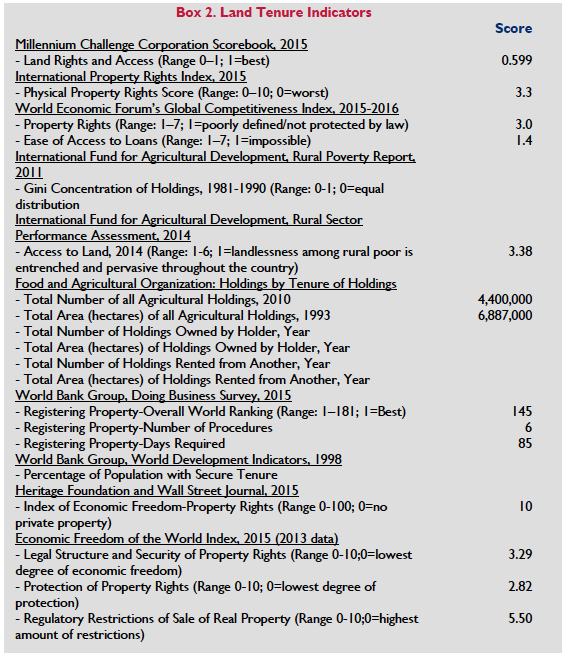

For land registration Burma relies on an antiquated deed registration system, where registration of land involves multiple ministries and can take 6-8 months to perfect title. It also lacks a comprehensive and accessible land information management system. Donors should continue to support the OneMap Initiative on land information as well as development of a new, more effective land title registration system.

Community forestry initiatives have strengthened the land rights of villagers, ensuring greater protection from land expropriation, as well as increased village participation in land governance. However, community forest groups have been both slow to expand and in some cases – as a result of their neglect of balanced agroforestry strategies, local needs, gender dynamics and marginalized groups – have adversely affected food security in villages. Donors should support the expansion of community forest user groups that encourage sustainable, equitable and participatory strategies in forest management and a review of the Forestry Law to determine how it could be revised to better facilitate community forestry.

Freshwater resources in Burma are abundant, but access to water is temporally and spatially uneven. Water quality has rapidly deteriorated as a result of urbanization, industrialization, and mining activities, along with a lack of adequate sanitation facilities. Insufficient data, as well as vague legislation and overlapping institutional authority, have hampered water management. Donors should help reduce water pollution by facilitating investment in sanitation facilities in both urban and rural settings. Donors could also offer technical assistance to help the government obtain better data on water resources and improve coordination of water management across agencies. Moreover, donors could continue to improve government capacity for sustainable hydropower planning to identify and prioritize the projects with the highest impact for development and poverty reduction. Finally, donors could provide continued support for the development of a National Water Law consistent with the National Water Policy.

Historically, Burma has lacked the necessary laws, regulations and enforcement mechanisms to protect its environment and vulnerable populations against the impacts of mining. Over the past two decades, these inadequacies have led to conflict and widespread environmental degradation in the wake of a rapid increase in large-scale mining. As investment in the country’s mineral sector increases, conflict between mining interests and local communities will likely increase. The effect of the newly-adopted amendments to the 1994 Mining Law has yet to be determined. Donors should help the government manage competing interests by supporting an analysis of the new Mining Law to determine how it might be improved so as to support investment while recognizing the rights of local communities. Donors could also help local communities protect their rights and interests through public-awareness building, community organizing and the development of contracting and negotiation skills. Specific attention should be given to developing a foundation for the negotiation of fair and equitable benefit-sharing agreements, with mechanisms to ensure that benefits reach all members of local communities. Finally, donors could provide continued support for Burma’s participation in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

Summary

Approximately 66 percent of Burma’s population lives in rural areas, and the majority depends on agricultural land as a primary means of livelihood. Burma is the poorest country in Southeast Asia, and poverty rates are particularly high in rural areas, where it is estimated that 30–50 percent of households are landless, and in border regions populated by minority ethnic groups.

Burma’s Constitution dictates that all land ultimately belongs to the state. The body of law governing land is expansive, complex and poorly harmonized, and dates back to the British colonial period. In 2012, the state enacted several high-profile laws whose effect on preexisting laws and systems is not yet clear. These include the Farmland Law and the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law (VFV Law). Burma adopted a new National Land Use Policy (NLUP) in early 2016 which will necessitate substantial revisions to the legal framework governing land tenure and administration.

Burma’s Constitution dictates that all land ultimately belongs to the state. The body of law governing land is expansive, complex and poorly harmonized, and dates back to the British colonial period. In 2012, the state enacted several high-profile laws whose effect on preexisting laws and systems is not yet clear. These include the Farmland Law and the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law (VFV Law). Burma adopted a new National Land Use Policy (NLUP) in early 2016 which will necessitate substantial revisions to the legal framework governing land tenure and administration.

Burma’s constitution guarantees women equal rights before the law, and the government claims that women have equal rights to administer property. Customary laws, which govern succession, marriage and inheritance, grant Buddhist women (the majority of women in Burma) equal rights in property matters. These customary laws and Burma’s statutory laws do not always govern in practice, however, and many women are subject to systems that do not afford them equal rights. Furthermore, Burma’s newest laws governing land (the Farmland Law and VFV Law) are not gender neutral and appear to lack a mechanism for the joint ownership of property between husbands and wives.

The primary central bodies governing land in Burma are: the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MoALI), whose departments are responsible for land-use planning, water resources, irrigation, mechanization, land management and administration, among other matters, concerning farmland; the General Administration Department (GAD) with the Ministry of Home Affairs, which has management authority over virgin, fallow and vacant lands; and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation (MoNREC), which has authority over the Permanent Forest Estate and mining lands. The Farmland Management Body (FMB) and the Central Committee for the Management of Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands (CCVFV), both established by laws enacted in 2012 and chaired by the head of MoALI, are responsible along with their lower-level branches for approving certain requests for land-use rights.

Burma’s land market has grown in the past two decades and has produced a particularly dramatic increase in the number of commercial landholdings. Prices have climbed in both urban and rural areas, due in part to land speculation. While there is some concern that inflated, prices will deter foreign investment in Burma’s land market, there is also alarm over prospects that increased foreign investment could lead to an epidemic of land confiscations. The law allows the state to use compulsory acquisition to acquire land for public purposes and for business purposes, neither of which the law defines in detail. Although Burma’s laws require the state to pay compensation for land it acquires, in practice the compensation often falls short of minimum standards or does not occur at all. The NLUP commits the government to adopting international best practices and observing human rights standards in its activities related to land acquisition, relocation, compensation, rehabilitation and restitution.

Natural resources are a leading source of conflict, and development projects have often involved Burma’s military forces, which have a history of displacing and violently abusing affected populations. Conflict and abuse have also surrounded the military’s confiscation of land in cases unrelated to development projects. Of particular concern in recent years is the forceful and uncompensated confiscation of land for urban expansion and for commercial, industrial and infrastructure projects. There have also been instances of forced confiscation of land resources by other groups in areas not under the control of the Union Government. As the state pursues an ambitious plan to convert vast amounts of land to industrial agricultural production, farmers are increasingly protesting what they call “land grabs.”

Burma has diverse natural forests, including tropical evergreen forests, hill forests and temperate evergreen forests. Forests cover approximately 48 percent of Burma’s land area. Deforestation due to excessive legal and illegal logging as well as traditional practices has emerged as a significant problem for Burma, with the country losing an average of 546,000 hectares of forest annually since 2010, the world’s third worst rate of deforestation.

Rapid exploitation of Burma’s natural resources is threatening the country’s agricultural and forest land. Large dam building, oil and gas extraction, mining, logging and large-scale agriculture projects are leading to severe soil and water degradation, as well as the forced displacement of smallholder farmers and minority ethnic communities.

Land

LAND USE

Burma is located on the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal and shares borders with Bangladesh, India, China, Laos and Thailand. It is the largest country in mainland Southeast Asia and has a land area of 653,508 square kilometers, of which 124,400 (roughly 19 percent) are agricultural (CIA 2015; World Bank 2015).

The country’s estimated 2014 GDP was $63.14 billion, with 42 percent attributed to services, 37 percent to agriculture and 21 percent to industry. Key exports include natural gas, wood products, pulses, beans, fish, rice, clothing, jade and gems. Primary agricultural products include rice, pulses, beans, sesame, groundnuts, sugarcane, fish and fish products and hardwood (CIA 2015).

The population of Burma is 56,320,206 with an annual growth rate of about 1 percent. Access to agricultural land is the most important resource for rural households. 66 percent of the population is rural. Fully 65-70 percent of the population is believed to be involved in agriculture, with women making up 49 percent of the agricultural labor force (World Bank 2015; CIA 2015; ADB 2011; FAO 2015).

Burma is the poorest country in Southeast Asia. Roughly 26 percent of the population lives below the poverty line (calculated as minimum necessary caloric and non-food expenditures), though that rate is slowly declining. (A different measure of poverty used by the World Bank finds a higher poverty rate of 37.5 percent.) The rural poverty rate is 29 percent, roughly twice the 15 percent poverty rate in urban areas (39 percent and 29 percent, respectively, using the World Bank analysis). Rural areas account for nearly 76 percent of Burma’s total poverty, and four states contribute the most to the national incidence: Ayeryawaddy (19 percent), Mandalay (15 percent), Rakhine (12 percent) and Shan (11 percent). Proportionally, the following states have the highest rates of poverty among their populations: Chin (73 percent), Rakhine (44 percent), Tanintharyi (33 percent), Shan (33 percent) and Irrawaddy (32 percent) (IHLCA 2011; UNDP 2014; WB 2014; WB 2015a).

Approximately 17 percent of Burma’s land is arable, 2 percent is permanent cropland, 0.47 percent is meadow and pastureland, and 48 percent is forestland. Approximately 25 percent of Burma’s agricultural land is irrigated (FAO 2011a; World Bank 2015; CIA 2015). Burma’s physical geography varies across its regions, which are divided into the Uplands, the Dry Zone and the Irrawaddy Delta. The Uplands contain hilly terrain that ranges from 1000 to 2000 meters in altitude, and stretch along the eastern, northern and western states of Kachin, Kayah, Kayin, Mon and Tanintharyi and Chin, as well as parts of Shan, Mon and Rakhine.

Approximately 17 percent of Burma’s land is arable, 2 percent is permanent cropland, 0.47 percent is meadow and pastureland, and 48 percent is forestland. Approximately 25 percent of Burma’s agricultural land is irrigated (FAO 2011a; World Bank 2015; CIA 2015). Burma’s physical geography varies across its regions, which are divided into the Uplands, the Dry Zone and the Irrawaddy Delta. The Uplands contain hilly terrain that ranges from 1000 to 2000 meters in altitude, and stretch along the eastern, northern and western states of Kachin, Kayah, Kayin, Mon and Tanintharyi and Chin, as well as parts of Shan, Mon and Rakhine.

Traditional shifting “swidden” agriculture is common in these areas. However, growing population density is forcing farmers to clear increasingly steep hills, where poor soil quality does not support sustained cultivation or allow for appropriate fallow periods. Many farmers in Shan and Kachin states have preferred to plant opium, a cash crop that they can harvest quickly and use to secure advance credit, rather than rice, which is easily looted and taxed by nearby combatants. Some farmers in the Uplands flat valley areas grow rain-fed paddy rice as well as corn, millet, ginger and coffee (COHRE 2007; WB 2014; Raitzer et al 2015; Woods 2015).

The country’s Dry Zone is a central heartland area that spans Burma’s semiarid region. Most farmers in this area are commercial farmers growing cash crops such as sesame, pulses and beans for export. Onions, potatoes, tomatoes and other seasonal vegetables are often grown on alluvial soils, and cotton is a common crop in the Dry Zone’s northern area. It is estimated that 7–10 acres of average land (or 15–20 acres of poor quality land) are required to sustain minimum standards of living for a family in this area. During slack seasons, many farmers migrate to Rangoon, Mandalay and border areas to find work. In addition to seasonal unemployment, people in the Dry Zone’s rural areas face frequent droughts and increasing land degradation in the form of loss of natural vegetation, soil erosion and deterioration of soil fertility (COHRE 2007; Kyaw and Routray 2006; Raitzer et al 2015; UOB 2005; IFAD 2013).

About 60 percent of Burma’s cultivated area is devoted to rice, which accounts for 43 percent of national agricultural commodity production value. Rice yields, as well as yields for other crops, tend to be lower than in other Asian countries and far below their potential; they are the second lowest in Asia. The Irrawaddy Delta area has been at the center of the rice economy since the British colonial period. In the Irrawaddy Delta, monsoon paddy cultivation is the most important income source for 25 percent of households. In households where rice cultivation is not the primary economic activity, members nonetheless practice small-scale or casual cultivation as a secondary source of income. Rice farmers sell about 75 percent of their crop at market, consume about 20 percent and reserve 5 percent for the next season’s seeds. Burma is a net exporter of rice and is estimated to have exported 324,000 metric tons in 2013, a significant decline from the previous year. (Pulses and beans are the largest export crops.) Many marginal farmers in the Irrawaddy Delta also engage in fishing or crabbing, but most do not own their own gear or boats and depend on traders for equipment. The region’s environment is deteriorating rapidly, and sources of fresh water, crabs, firewood and vegetables are scarce (WB 2014; Raitzer et al 2015; COHRE 2007; LIFT 2011; Suwannakij 2012; WB 2015a).

Burma has an exceptional level of biological diversity and is home to Asia’s most extensive intact tropical forest ecosystems. These include delta mangroves, lowland tropical rainforests, teak forests (including the world’s only remaining golden teak forests), semi-deciduous forests in the north, and sub-alpine forests in northern Kachin State. Widespread forest loss and degradation due to logging, hunting, mining and other extractive industrial activities has become a serious problem, threatening ecosystems and leading to floods, soil erosion and landslides, which result in sedimentation build-up behind dams and river siltation, ultimately reducing the amount of available surface water. Erosion washes away nutrient-rich topsoil, reducing the land’s fertility, which, when combined with the reduced availability of water, stunts agricultural productivity (BEWG 2011; IRIN 2011).

Burma’s five main rivers are the Irrawaddy, Chindwin, Salween, Sittaung and Tenasserim. Some of these contain endangered species. Each of these rivers has piqued investor interest in their hydropower and irrigation potential. Livelihoods in rural Burma depend heavily on rivers and streams, many of which are under threat from development of large dams that could result in submersion of agricultural and forest land and the forced relocation of local communities (BEWG 2011; International Rivers Watch 2014).

Government promotion of large-scale monoculture plantations increased since 2008 under the presidency of Thein Sein, though it appears the newly elected Government led by the National League for Democracy is placing greater emphasis on smallholder farmers, crop diversification and land tenure security in accordance with the new Agriculture Policy (2016) and draft Agriculture Development Strategy. These plantations, some of which are threatening ecological integrity, food security and the livelihoods of local farmers, typically grow annual crops such as cassava, sugar cane and paddy rice, and industrial crops such as palm oil and rubber (BEWG 2011; Woods 2015a; MoALI 2016).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Roughly 66 percent of Burma’s population lives in rural areas. The great majority of this population is poor and depends on land-based resources as a primary means of livelihood (CIA 2015; FAO 2015).

Burma’s government has reported that the country has 8 major ethnic groups and 135 sub-ethnic groups. Ethnic Burmans constitute around two-thirds of the population. Together, Burma’s ethnic minorities constitute about 35 percent of the total population. The largest minority groups are the Shan (9 percent) and the Karen (7 percent), while the remaining groups – which include the Mon, Rakhine, Chin, Kachin, Karenni, Kayan, Chinese, Indian, Danu, Akha, Kokang, Lahu, Naga, Palaung, Pao, Rohyinga, Tavoyan, and Wa groups – each constitute 5 percent or less of the population (IFAD 2013; MRGI 2007; COHRE 2007).

Most of Burma’s minority ethnic groups live in the country’s border regions, where poverty is most acute. These same areas hold most of Burma’s valuable natural resources, are most affected by the country’s decades-long civil war and account for the greatest share of small and marginal landholdings. Less than 5 percent of the households in eastern Shan State have farms larger than 5 acres. In Kachin State and Chin State, only 25–28 percent of households have farms larger than 5 acres (Ash Center 2011; Hudson-Rodd 2004; MRGI 2007; BEWG 2011; FAO 2014).

Burma’s average farm size (6 acres) is moderate by Southeast Asian standards and low by international standards. Farm size does, however, vary considerably across states, with the largest average sizes found in Irrawaddy (11.2 acres) and Yangon (9.3 acres) and the smallest in Chin State (1.7 acres). In the Dry Zone, farms average 4.5 acres, compared to 10 acres in the coastal and delta areas and 2 acres in hilly areas. About one-third of all farmers have farms of one hectare or less (IFAD 2013; IHLCA 2011; FAO 2014; WB 2015a).

Estimates of landlessness among Burma’s rural population range from 30 percent to 53 percent depending on the source of the estimate and how “landless” is defined. Under any definition, poverty in Burma is closely associated with landlessness or functional landlessness (holdings of less than 2 acres), especially in the Delta, Coastal and Dry zones, however, the incidence of landlessness varies by region. One study, which defined landlessness as having no land use rights to cultivable land, found that the proportion of landless households is highest in the Ayeyarwaddy region in lower Burma followed by the Dry Zone in central and western Burma. That study reported that other heavily affected areas include Kachin and Mon States. Increasing numbers of people have been displaced from their land in Shan, Tanintharyi, Rakhine and Chin States as Burma’s military has established bases in these areas (IFAD 2013; MSU and MDRICESD 2013; World Bank 2014; Reuters 2012; COHRE 2007; Hudson-Rodd 2004).

Evolving dynamics in the agricultural sector are changing the distribution of land in Burma. Government allocation of land resources to commercial agriculture companies is on the rise, but is unfolding differently across the country. In general, the government is able to grant leases of lands at the disposal of the state in areas under its political control, which include the central Dry Zone, Yangon Region and Ayeyarawaddy Region.

As mentioned above, the previous government promoted the establishment of large-scale monoculture plantations. The previous government’s Master Plan for the Agriculture Sector (2000-2030) called for 10 million acres of new private agriculture plantations. MoALI’s new Agriculture Policy, released in December of 2016, places far greater emphasis on supporting smallholder farmers, crop diversification and land tenure security. At the same time, acreage for rubber, Burma’s most widely planted industrial crop, more than tripled from 2004 to 2014. While most rubber production is in southern Burma, especially in Mon State, major expansions of large-scale rubber plantations have taken place in Kachin State, northern Shan State and the Wa autonomous region, often to the detriment of small-scale upland farmers who are displaced from their land, often without compensation. (BEWG 2011; Woods 2011; UOB 2014 (Min. of Ag); MCRB 2015; Global Witness 2015; MoALI 2016).

Oil palm plantations, for which companies burn and clear-cut land, are centered in Tanintharyi Region in southern Burma. Businessmen from Burma own the majority of oil palm plantations, while the military and smallholder farmers cultivate a very small percentage (UOB 2014 (Min. of Ag) BEWG 2011; Woods 2011).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Burma’s current legal framework is the product of several distinct periods in the country’s history, including the British colonial period (1886–1948), post-colonial independence (1948–1962) and decades of rule by a military junta (1962- 2011) and post-junta rule, including the election in 2016 of the democratically elected government of Htin Kyaw (2011-present). Because many of the laws from these periods are still in effect, the body of law governing land in Burma is expansive, complex, and characterized by vague, conflicting and overlapping provisions. Laws affecting land in Burma are also poorly harmonized, as legislation is typically sector-specific and does not cross-reference or take into account other relevant and preexisting acts. One survey of the legal framework found that in 2009 at least 73 active laws, amendments, orders and regulations had a direct or indirect bearing on housing, land and property rights. Although the government repealed a number of statutes in 2012, ambiguity and confusion in the land laws remain. The government engaged in a lengthy multi-stakeholder process to adopt a new National Land Use Policy (NLUP) that is intended to provide a foundation for future land governance reforms in the country, including the harmonization of the confusing array of often antiquated laws relating to land tenure security. The public consultation process used for developing the NLUP provides a model for other policy and law development in the country. (Displacement Solutions 2012; Leckie and Simperingham 2009; Mark 2015; Srinivas and Hlaing 2015, Oberndorf, et. al. 2017).

Burma’s constitution was adopted in 2008 and came into force in 2010. While it requires all other laws, rules, regulations and policies to comply with its provisions, it also established a republic in which states, regions, divisions and zones have authority to enact their own laws so long as they do not conflict directly with the constitution or national laws, rules and regulations (UOB Constitution 2008a).

The constitution contains numerous provisions relating to land. It reconfirms that the government owns all land, stating that “the Union is the ultimate owner of all lands and all natural resources above and below the ground, above and beneath the water and in the atmosphere in the Union.” It grants citizens the right to settle and reside anywhere in the country, establishes the right of private property and inheritance, and provides that the state shall protect lawfully acquired moveable and immovable property as well as the privacy and security of home and property (UOB Constitution 2008a, Art. 37).

After several parliamentary votes and months of debates and consultations, the parliament adopted the Farmland Law in March 2012. The law defines rights and responsibilities relating to tenure and establishes a hierarchy of management over farmlands (Displacement Solutions 2012; Displacement Solutions 2015).

The Farmland Law affirms that the state is the ultimate owner of all land and creates a private-use right that includes the right to sell, exchange, inherit, donate, lease and “pawn” farmland. It also establishes a system of registered land-use certificates (LUCs) (further discussed below). This law provides that Farmland Management Bodies are to issue LUCs to farmers and that Land Records Departments are responsible for registering land rights and collecting related fees. The law: does not describe the process farmers should use to apply for LUCs and register their rights; provides only a very basic description of the government entities involved in the process; and leaves the details of implementation for the executive branch of government to define. Nevertheless, as of March 2016, about 8 million LUCs are reported to have been issued since the necessary rules, guidelines and forms were put into place in 2013 despite ongoing capacity and implementation challenges. The MOAI has also issued rules for the implementation of the Farmland Law (Oberndorf 2012; UOB Farmland Law 2012b; UOB 2012; Srinivas and Hlaing 2015; Allaverdian 2016).

The Farmland Law (2012) repealed and replaced the Land Nationalization Act (1953), the Disposal of Tenancies Law (1963) and the Agriculturalists’ Rights Protection Law (1963). It also covers: conditions under which farmers can retain farmland use-rights; the state’s power to rescind such rights; the process for settling certain land-related disputes; and basic requirements for compensation in the case the government acquires the farmland for public purposes (Htun 2012; UOB Farmland Law 2012b).

The Foreign Investment Law of 2012, as amended in 2015, governed foreign investment in land-related projects. It created the Myanmar Investment Commission, which is charged with examining and accepting certain investment proposals, issuing permits and suspending the permits of investors who fail to abide by the law’s provisions. The law granted substantial tax relief to foreign investors, including a five-year tax holiday for businesses involved in the production of goods or services, or in business deemed by the Commission to be beneficial to the Union. The law also provided significantly greater authority to the regional and state governments to receive and approve foreign investments. A new consolidated Investment Law, which merged the Foreign Investment Law and the domestic Investment Law into one, was enacted in October of 2016. (UOB Environmental Conservation Law 2012a; Oberndorf 2013; Mayer Brown 2012; Min of Planning and Econ 2013; UOB 2013; Stephenson Harwood 2016; Myanmar Business Today 2016; UOB 2016).

The Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law of 2012 (VFV Law) governs the allocation and use of virgin land (i.e., land that has never before been cultivated) and vacant or fallow land (which the law characterizes as for any reason “abandoned” by a tenant). As described further below, the law establishes the Central Committee for the Management of Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands (CCVFV), which is responsible for granting and rescinding use rights for such lands, increasingly through state and regional level bodies established by the VFV Law. The General Administration Department of the Ministry of Home Affairs plays a significant role in VFV land administration as it is often responsible for processing the required application forms. The VFV Law also lays out: the purposes for which the committee may grant use-rights; conditions that land users must observe to maintain their use rights; and restrictions relating to duration and size of holdings (Htun 2012; Oberndorf 2012; Belton, et al, 2015).

The Land Acquisition Act of 1894 (further discussed below) provides the basis for the state to acquire land for public and other purposes. Its provisions address: required notice; procedures for objecting to acquisition; land valuation methods; the process for taking possession of land; the process for appeals; and rules for the temporary occupation of land (UOB Land Acquisition Act 1894; Displacement Solutions 2012; Srinivas and Hlaing 2015).

There are potentially dozens of other laws that relate directly or indirectly to land management, land use and land as property in Burma. Chief among these are: the 1882 Transfer of Property Act, which governs the sale, mortgage, lease, exchange and gift of moveable and immovable property; the 1879 Land and Revenue Act, which governs assessment and collection of land taxes; the 1899 Lower Myanmar Town and Village Act, which governs the land rights in towns and villages and provides for certain rights (such as the right to cultivate and right to sell) relating to hereditary and government lands; the 1893 Partition Act, which governs partition of immovable property; and, the 1909 Registration Act, which governs the registration of dwellings and instruments of immovable property. Although an analysis conducted in 2009 found these laws to be still in place, it is not entirely certain that this is still the case (Leckie and Simperingham 2009; Displacement Solutions 2012; Mark 2015).

For certain matters in Burma, customary laws apply with the force of formal law. According to the 1898 Burma Laws Act, which appears to be still in effect, Buddhist, Muslim and Hindu customary laws govern matters of succession, inheritance and marriage for their respective adherents. The Buddhist Women’s Special Marriage and Succession Act of 1954 codifies some Buddhist customary law on these issues as well. For Christians, rules of succession, inheritance and marriage are governed by the Christian Marriage Act, the Burma Divorce Act (which applies only to Christians) and the Succession Act of 1925 (Sen 2001; Leckie and Simperingham 2009; Gutter 2001).

Although the law recognizes customary practices regarding succession, inheritance and marriage, the laws of Burma do not recognize the authority of other customary land-use practices. Earlier, the British had recognized the authority of a few such practices for certain Upland areas in northern and western Burma. For example, the Kachin Hills Manual respected the customary authority of Kachin headmen to rule on land uses within the community, and the Chin Hills Regulation of 1896 and the Chin Special Division (Extension of Laws) Act of 1948 recognized the Chin’s customs. Today, however, Burma’s statutory laws do not recognize customary land-use practices (BEWG 2011; Transnational Institute 2015; MCRB 2015).

The NLUP was adopted in early 2016 following a lengthy, multi-stakeholder process. It has several objectives including: promoting sustainable land use, natural resource and environmental management; strengthening land tenure and food security for all citizens; recognizing and protecting customary tenure rights; developing fair and accessible dispute resolution mechanisms; promoting inclusive decision-making, responsible investment in land and natural resources and effective land administration, Strategic development of a new legal and regulatory framework relating to land governance in the country will help to accomplish these objectives. The development, over time, of a new legal framework is likely to bring about important changes to many, if not all, of the laws described above and throughout much of this profile (National Land Use Policy 2016).

TENURE TYPES

The state is the ultimate owner of all land in Burma. All private tenure rights are somewhat limited. Tenure rights vary depending on the type of land involved, as reviewed below. There is a right to sell, lease, inherit or mortgage the rights to most categories of land, subject to the state’s underlying ownership (UOB Constitution 2008a).

Between 1850 and 1988, Burma adopted a multitude of laws that combined to create a complex assortment of land classifications. The extent to which the land classifications may have been simplified as the result of the enactment of several new laws in 2012 is unclear. At least 12 categories, some of which have changed, existed as of 2009: freehold land, grant land, agricultural land, garden land, grazing land, cultivable land, fallow land and waste land, forest land (discussed later in this profile), town land, village land, cantonment land and monastery land (UN-Habitat n.d.).

Freehold land. Freehold land equates roughly to ‘ancestral land,’ existing mostly in urban areas and rarely in small towns and villages. Freehold land is transferrable, not subject to land revenue taxes and can be taken by the state only pursuant to laws on compulsory acquisition (UN-Habitat n.d.; Leckie and Simperingham 2009; Displacement Solutions 2012).

Grant land. Owned and allocated by the state, grant land is common in cities and towns, but rare in village areas. The state may lease grant land out for extendable periods of ten, thirty, or ninety years. Grant land is transferable, is subject to land tax and may be reacquired by the state during a lease period in accordance with laws governing compulsory acquisition (UN-Habitat n.d.; Displacement Solutions 2012).

Farmland. Farmland, as defined in the Farmland Law (2012), appears to have replaced the ‘agricultural land’ classification, and includes: garden land; paddy lands; dry land (ya); alluvial land (kiang); perennial plant land; coastal land (dhani); hillside cultivation land (taungya); alluvial lands; and land for growing vegetables and flowers (UOB Farmland Law 2012b; Oberndorf 2012; UN-Habitat n.d.).

With the enactment of the Farmland Law (2012), those seeking rights to farmland must obtain permission and a land-use certificate (LUC) from the state. Farmland is transferable through sale, lease, inheritance and donation, with the condition that transfers must be registered with the state. Farmland rights may also be “mortgaged” as security for a loan, with the condition that the loan can only be used to finance agricultural production. Unless the user obtains express permission for other uses, land held under a farmland use right must be used for permitted purposes (i.e., for agricultural purposes and for “regular” crops, which the law does not define). The user cannot allow the farmland to remain fallow without sound reason and cannot transfer the use right to a foreigner or an organization that includes a foreigner without state permission (UOB Farmland Law 2012b, Arts. 12–14).

Grazing land. The Upper Burma Land Revenue Regulations of 1889 established the classification of grazing land, which the 2012 Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law (VFV Law) now includes within the definition of virgin land. In the past – and possibly still – grazing land was for use by cattle of nearby villagers, was protected from trespassers and was not subject to land taxes (Oberndorf 2012; UOB Foreign Investment Law 2012c; UN Habitat n.d.).

Town land. In most cases, town land is the same as freehold land or grant land. An exception, however, is when it refers to La Na 39 land, a category named for its authorization under article 39 of the 1953 Land Nationalization Act. Usually, La Na 39 land is farmland (previously known as agricultural land) that has been re-categorized for another purpose (e.g., for building houses or digging fish ponds). La Na 39 land is transferable, and those who have it registered under their name must pay land tax to the government. Because the Farmland Law repealed the Land Nationalization Act, it is unclear whether the La Na 39 category still exists (UN Habitat n.d.; Displacement Solutions 2012).

Village land. Village land is land located outside the parameters of town land and can either be grant land or La Na 39 land. Village land is transferable, but only if it has been transformed into La Na 39 land or grant land. Those with village land must pay land tax to the government unless their plot is less than one-fourth of an acre and occupied by a building (UN-Habitat n.d.; Displacement Solutions 2012).

Cantonment land. Cantonment land is land that the state has acquired for the military’s exclusive use. When an area is earmarked as cantonment land, the government issues a declaration of the designation, and the state acquires it under the Land Acquisition Act, which provides that owners should be compensated if the land was classified as freehold land, grant land or La Na 39 land. Although in the past the government was not required in this circumstance to invoke the Land Acquisition Act or to provide compensation for other types of land (e.g., agricultural land, now farmland), under the Farmland Law it must do so. The military is required to surrender cantonment land to the government once it is no longer necessary for military use (UN-Habitat n.d.; Displacement Solutions 2012; Oberndorf 2013).

Monastery land. Monastery land is that which the Ministry of Home Affairs has declared as such. If that land is freehold land, grant land, La Na 39 land or farmland, the government must invoke the Land Acquisition Act, and the state must pay compensation to the right holders before acquiring the land for use as monastery land. Land classified as monastery land is not subject to land taxes and retains its classification for eternity (UN-Habitat n.d.; Displacement Solutions 2012; Oberndorf 2013).

Vacant, fallow and virgin land. The 2012 VFV Law defines and governs vacant, fallow and virgin land, categories that have replaced what was known previously as culturable, fallow and wasteland. It also created the Central Committee for the Management of Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands, which replaced the Central Committee for the Management of Culturable Land, Fallow Land and Waste Land (UN-Habitat n.d.; Leckie and Simperingham 2009; Oberndorf 2013).

According to the VFV Law, land users who hold use rights to vacant, fallow or virgin land cannot mortgage, give, sell, lease or otherwise transfer or divide land without permission from the Union Government. That law also sets out parameters regarding the amount of vacant, virgin or fallow land that the state may grant to a user, and the duration for which it may be granted (Oberndorf 2012).

The size and duration restrictions, which differ according to the purpose to which the land will be put, cover the following seven categories of use: (1) perennial plants and industrial crops; (2) orchards; (3) use by a rural farmer and a family; (4) aquaculture; (5) breeding and raising of livestock and poultry; (6) mining; and (7) ‘other.’ The restrictions are as follows.

- Land to be used for the cultivation of perennial plants and industrial crops can be granted in quantities of up to 5000 acres at a time. Once cultivation is underway on 75 percent of the permitted acres, an additional 5000 acres can be added at a time up to a total of 50,000. Grants for perennial crops can be for up to thirty years, while grants for seasonal crops shall continue for as long as there is no breach of conditions (UOB Vacant Fallow and Virgin Lands Law 2012d).

- For orchards, the upper limit is 3000 acres. Land to be used for this purpose can be granted for up to thirty years.

- Up to 50 acres of land can be granted to a rural farmer and a family.

- Land to be used for aquaculture can be granted in the amount of up to 1000 acres, with the duration of rights being up to thirty years.

- The amount of land granted for use in the breeding and raising livestock and poultry depends on the kind of animals to be kept on the land. For buffaloes, cows, and horses, up to but not exceeding 2000 acres; for raising sheep and goats, 500 acres; and for keeping chickens, ducks, pigs and quails, 300 acres. Depending on the type of livestock, grants can be for up to thirty years.

- Acreage and duration allowed for mining purposes are as permitted by the Union Government and relevant ministries.

- Acreage and duration restrictions applying to other uses are as permitted by the Union Government and relevant ministries (Oberndorf 2012; Displacement Solutions 2012).

Burma’s laws distinguish between tenure held by citizens and foreigners. Under the Investment Law of 2016 and implementing rules enacted in early 2017, foreign firms may fully own ventures, andmay also contract to use land for a number of activities that are not restricted. In general, the new Investment Law and implementing rules framework are significantly liberalized from the earlier Foreign Investment Law framework put into place in 2013. Foreign investors may lease land from the government or from authorized individuals for up to 50 years, depending on the type and size of the investment, and such arrangements may be extended twice, for ten years each time. For investments in areas of the country that are less developed, a new tax incentive regime has been put in place. A range of agriculture and farming activities have been included in promoted sectors under the new investment rules, including activities in the forest sector. In addition, the Special Economic Zone Law allows foreign firms to lease land for 50 years with one 25-year renewal period if the firms meet certain requirements. There are 3 SEZs under active development: Thilawa in the Yangon area, Dawei in Tanintharyi Region and Kyaukphyu in Rakhine. All three zones have, however, been met with protests from local land rights holders (UOB Investment Law 2016; UOB 2017 (Investment Law Rules); UOB Special Economic Zone Law 2014; MCRB 2015).

Customary tenure. In addition to statutory tenure types, the people of Burma practice a plethora of customary tenure arrangements. Although the British formalized some of these during their colonial rule, customary tenure arrangements do not enjoy formal legal recognition today. Military regimes that succeeded the British period have in practice denied the existence of customary land tenure forms, which are nevertheless common in rural areas, and customary institutions remain a primary source of authority for land management (BEWG 2011; Leckie and Simperingham 2009; Transnational Institute 2015; USAID 2016).

Customary tenure arrangements tend to prevail in ethnic areas in the Uplands (where for the most part the state has not maintained a presence) but are in decline due to war and conflict that has caused local populations to abandon their land (BEWG 2011; COHRE 2007; Transnational Institute 2015).

Land-use customs vary among different ethnic groups and often within them as well. The Karen ethnic group, which comprises about 7 percent of Burma’s population, tends to practice shifting cultivation, or swidden farming, during which they clear forests then allow them to regenerate for 10 to 12 years before re-cultivation. Some Karen populations classify various forest areas as rotational farms, irrigated farms, orchard farms, communal forest, grazing land and sacred forest (COHRE 2007; MRGI 2007).

In addition to rubber and irrigated low-lying paddy fields, the Mon ethnic group cultivates many of the same crops as the Karen, although it is unclear whether they classify tenure types along similar lines (COHRE 2007).

Although the government does not legally recognize customary land-tenure arrangements, in fact a complex and informal overlap between statutory laws and customary practices exists. In some cases, land records officials document customary agricultural land plots in their land surveys, which the state later ignores if an influential developer becomes interested in acquiring the land (BEWG 2011).

It is important to note that recognizing and protecting customary land rights is one of the objectives of the NLUP. The NLUP specifically calls for recognition of customary land use systems in the upcoming national land law in order to ensure the formal recognition and protection of customary land rights (UOB National Land Use Policy 2016).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

According to a Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MoALI) (until 2016 known as the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation) report, as of 2007 roughly one-third of agricultural households had inherited their land and slightly more than 20 percent had purchased it. How the remainder of agricultural households acquired their land is unclear. Also unclear is whether these statistics represent land acquired through both formal and informal channels (Woods 2011).

As of 2012, several new laws govern the process for acquiring rights to agricultural and other types of land in Burma. The 2012 Farmland Law, establishes the formal process farmers must use to procure farmland, requiring farmers to: obtain a land use certificate (LUC); pay fees; and register land rights through a process (described in more detail below) that involves various local management bodies. The Farmland Law also places numerous restrictions on the right to use farmland. Infringement of regulations may result in imprisonment for up to three years, a fine equivalent to roughly US $1100 and the confiscation of materials related to the breach. Prohibited are: using farmland for non-agricultural purposes without permission; growing crops other than “regular” crops (which the Farmland Law does not define) without permission; leaving farmland fallow without a sound reason; without permission transferring land to a foreigner or to an organization that includes a foreigner; failure to register the transfer of a use right and failure to pay associated fees; and mortgaging a farmland use-right for any reason other than securing a loan to finance investment for agricultural production, or borrowing from any entity other than a government bank or authorized bank (UOB Farmland Law 2012b; Displacement Solutions 2012; Oberndorf 2012).

The Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law (VFV Law) of 2012 governs the formal process for obtaining access to vacant, fallow and virgin lands. Public citizens, private investors, government entities and others may acquire rights to use this land by submitting an application to the Central Committee for the Management of Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands. The 2012 law recognizes that farmers are already using vacant, fallow and virgin land without formal government permission, and outlines a basic mechanism for them to obtain a LUC.

Although farmers are technically eligible to receive vacant, fallow and virgin land, in practice the government allocates such land primarily to private entrepreneurs, companies and state enterprises (Woods 2011; Oberndorf 2012; Displacement Solutions 2015).

Before acquiring land use rights from citizens or the state, foreigners must submit a proposal to and obtain a land rights authorization from the Myanmar Investment Commission if required under the new Investment Law legal framework. The Investment Law explicitly protects foreign investments from suspension, nationalization or other forms of expropriation within the term or extended term of the investment contract and provides for due process of law and appropriate compensation being paid. (UOB Farmland Law 2012b; UOB Environmental Conservation Law 2012a; UOB 2017 (Investment Law Rules); MCRB 2015).

Despite the formal laws governing the process for securing land rights, many in Burma acquire land through customary and informal systems. These systems and processes appear to vary by type of land, ethnic group and region.

Historically, farmers in lowland areas have tended to rely on informal social systems to secure land access, although many have been able to obtain LUCs since enactment of the Farmland Law, especially in areas where there are cadastral maps. Fewer LUCs have been issued in more remote lowland areas where such maps tend to be missing. The Mon, most of whom live in lowland areas, generally acquire land by inheriting it from their parents. This may be changing, however. As population pressure, conflict and land scarcity increase, the Mon are increasingly leaving and selling family land (known as ‘legacy land’) to neighbors and outsiders. In addition to inheriting land, the Mon sometimes appropriate it from uncultivated spaces (including forests) in dual administrative areas, which are controlled jointly by the central government and the New Mon State Party, or from areas administered wholly by the New Mon State Party. In both cases, the Mon typically register their land with the local party authorities (Transnational Institute 2013; COHRE 2007; BEWG 2011; Allevardian 2016).

According to Karen customary practices, all land ultimately belongs to the village, though in some cases it may be owned privately, usually only by men. Many Karen families inherit and live on the land their ancestors held, and for the most part do not sell or transfer this land. In some areas, armed opposition groups such as the Karen National Union issue informal land titles that can help increase tenure security for people in conflict-affected areas. The Karen National Union issued a draft land use policy in 2014 (COHRE 2007; Faxon 2015).

The disparity between formal rules and unofficial land allocation practices seems to exist in relation to agribusiness as well. In northern ethnic states, businesses have negotiated land deals with military commanders or leaders of ethnic political organizations. Local farmers were then dispossessed of their lands, often without compensation, by military or police officials. In southern ethnic states or regions such as Rakhine, Mon and Tanintharyi, the MoALI appears to be involved in allocating land. In Burman areas in the central Dry Zone and Delta region, MoALI oversees the allocation of land to companies (Woods 2011; Anderson 2014).

The extent to which informal systems dominate land acquisition methods in Burma is unclear. MoALI reported in 2007 that nearly a quarter of agricultural households claimed to have title for their land in rural Upland areas, where customary land-tenure systems prevail, most households do not have land titles. Land titles became a feature of Burma’s land administration during the British colonial period, when the country adopted a deed registration system, through which people were granted a deed to land based on the inclusion of their landholdings in a state-controlled register pursuant to the Registration Act of 1909 and the 1946 Burma Registration of Deeds Manual. That system was mostly replaced during the socialist period with the passage of the 1953 Land Nationalization Act, under which temporary or permanent leaseholds (depending on the type of land) were allocated to farmers and evidenced in the form of annual tax certificates issued by the Department of Agricultural Lands Management and Statistics (DALMS)). Later in the socialist period, the Disposal of Tenancies Act created a landlord-tenant system under which land was distributed to ‘laborers,’ who farmed in accordance with government directives and owed a portion of crops to the government. This created a complicated mix of permanent rights created under the Land Nationalization Act and temporary rights mostly governed by the Disposal of Tenancies Act. The 2012 Farmland Law replaced the system established during Burma’s socialist period. Although the law provides for a system involving land-use certificates, the mechanisms for realizing this scheme that are in place are difficult for smallholders and those with customary rights to comply with, as explained below (BEWG 2011; Transnational Institute 2013; COHRE 2007; Woods 2011; Oberndorf 2013; Srinivas and Hlaing 2015).

Smallholder farmers all across Burma face tenure insecurity. Especially vulnerable are those whose land use does not match official land classifications. This includes a large portion of the smallholder farmers in the delta area. Shan State and other areas of the country who are farming land that is technically classified as reserve forest land in maps that date as far back as the early 20th century. Also vulnerable are smallholder farmers who over the years have intentionally avoided reporting their land use to the government in order to escape onerous land taxes (Oberndorf 2013).

Certain aspects of Burma’s laws contribute to tenure insecurity. The 2012 Farmland Law reaffirms the government’s power to take tenured lands for any reason deemed to be in the state’s interest as well as for a variety of violations, such as failure to pay fees or to register use rights (e.g., after inheriting them). Problems with implementation have in some cases undermined the tenure security of smallholders who have found the LUC process especially problematic for a number of reasons: 1) areas for which the government had no previous records, conflict-prone areas and non-farm lands are not covered by the process; 2) the LUCs themselves have been drafted by hand and are error-prone and vulnerable to destruction by bad weather; 3) boundaries of parcels covered by LUCs have been determined without consulting the landholders; and 4) because they do not understand the benefits of the system many who have received LUCs have not recorded subsequent transactions for the land. However, the NLUP explicitly seeks to strengthen land tenure security for all people in Myanmar. Significant changes to law, along with improvements in the capacity of responsible government authorities, will be required to achieve this objective (OECD 2014; Srinivas and Hlaing 2015; Displacement Solutions 2012; Oberndorf 2013; Oberndorf 2012; National Land Use Policy 2016).

Those relying on customary tenure rights are particularly insecure, as Burma’s laws do not recognize customary use rights. As discussed further below (under Compulsory Acquisition of Private Property Rights by the Government), language in the VFV Law may put people using shifting cultivation methods at risk of having their land deemed vacant or fallow and then confiscated. Provisions in the VFV Law and the Farmland Law may provide an opportunity to protect the interests of smallholder farmers, however. Article 25 of the VFV Law states that where a right to use vacant, fallow or virgin land is granted, the CCVFV should work with relevant government departments and organizations to protect the interests of farmers who are already utilizing the lands, even if their use is not formally recognized. Furthermore, the Farmland Law permits that vacant, fallow and virgin lands may be reclassified as farmland if a Farmland Management Body determines that the use of that land is stable. More broadly, one of the objectives of the NLUP is to recognize and protect customary tenure rights, an objective that may lead to significant changes in the legal framework as it relates to such rights (Htun 2012; Srinivas and Hlaing 2015; Transnational Institute 2013; Displacement Solutions 2012; Oberndorf 2013; Oberndorf 2012; National Land Use Policy 2016).

Under the previous government, the state’s ambitions for agricultural land threatened tenure security. The Thein Sein government created a 30-year (2000–2030) Master Plan for the Agricultural Sector which aimed to convert 10 million acres of fallow and virgin land to agricultural production. (This policy is likely to be replaced by the new NLD government.) In line with this policy, the acquisition of land by corporate and private entities grew rapidly in recent years, often at the expense of smallholders and communities who follow customary practices. By 2001, the state had allocated more than 1 million acres to about 100 enterprises and associations. According to one study, by 2011, 204 national companies had obtained roughly 2 million acres, mostly in Kachin State and the Tanintharyi Region. Another found that the government has issued more than 5.2 million acres of agricultural land concessions to private companies. In 2016 the new government replaced the previous policy with a new agriculture policy that moves away from openly promoting large agro-industrial developments. Instead, the language in the new policy places much greater emphasis on the interests of smallholder farmers, crop diversification, and land tenure security. (Woods 2011; Landesa 2013; Displacement Solutions 2015; MoALI 2016).

There is some concern that the administrative bodies and processes established under the 2012 Farmland Law are prone to corruption, and lack safeguards necessary for ensuring that land rights are secure. For example, farmers have no representation at some levels of the Farmland Management Body, which is responsible for resolving certain land disputes and empowered to approve, issue and revoke land-use rights. Rather, that body is populated primarily with various executive branch officials and, at more local levels, with individuals for whom there are no selection criteria. It has been suggested to the Director General of the DALMS that the Farmers’ Association and its local-level subsidiaries (whose creation is permitted under the Farmland Law for the improvement of farmers’ socioeconomic wellbeing) be included in Farmland Management Bodies (further discussed in ‘Land Administration and Institutions’ below). Although the suggestion was well-received, it is unclear whether steps will be taken to bring the idea to fruition (Oberndorf 2013; Displacement Solutions 2012; Landesa 2013).

Armed conflict functions to reduce tenure security as well. The government has been engaged in peace negotiations with some of the armed groups. It is unclear whether a peace agreement signed by 8 of 20 non-state armed groups in October 2015 will reduce the impact on tenure security in at least some areas. Less than a quarter of Burma’s conflict-affected population possess legal title deeds or other formal legal recognition for their land tenure claims, and less than 12 percent of civilians hiding from military patrols possess identity cards, which are necessary (or were, as of 2007) for obtaining legal title. It is presently unclear whether possession of an identity card is necessary to obtain legal land titles (COHRE 2007; Irrawaddy 2016).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Burma’s constitution guarantees women equal rights before the law and prohibits the government from discriminating against any citizen on the basis of sex. According to the government, women also have equal rights to enter into land-tenure contracts and to administer property (UOB 2008b; CEDAW 2007).

Burma’s newest land legislation – the Farmland Law and the VFV Law – is not conducive to equal rights for women. Rather than explicitly recognizing women’s equal rights, these laws state that land will be registered to the head of a household, which in Burma is understood to mean the husband. In addition, these laws appear to lack a mechanism for joint ownership of property by a husband and wife, and do not explicitly state the equal rights of women to inherit land or be granted use rights for vacant, fallow or virgin land. (Displacement Solutions 2012; Oberndorf 2012; Faxon 2015; Srinivas and Hlaing 2015).

Burma’s newest land legislation – the Farmland Law and the VFV Law – is not conducive to equal rights for women. Rather than explicitly recognizing women’s equal rights, these laws state that land will be registered to the head of a household, which in Burma is understood to mean the husband. In addition, these laws appear to lack a mechanism for joint ownership of property by a husband and wife, and do not explicitly state the equal rights of women to inherit land or be granted use rights for vacant, fallow or virgin land. (Displacement Solutions 2012; Oberndorf 2012; Faxon 2015; Srinivas and Hlaing 2015).

However, the NLUP contains provisions that could lead to a strengthening of women’s land rights. One of its guiding principles is the promotion of participation by women in decisions concerning land and natural resource management. It explicitly seeks to recognize and protect the land tenure rights of women (and others). The policy provides that the new national land law should provide women with rights equal to men in all aspects of land tenure, land management, land use and related decision-making (National Land Use Policy 2016).

Women’s land rights vary by religious affiliation. As discussed above, Buddhist, Muslim and Hindu customary laws have the force of formal law for their respective populations in matters of succession, inheritance and marriage. The Buddhist Women’s Special Marriage and Succession Act of 1954, which applies to Buddhist women in these matters, also codified some Buddhist customary law.

Burma’s government has reported that customary Buddhist law dictates that Buddhist women – a group that includes the majority of women in Burma – have rights equal to their husbands’ regarding the ownership of property and are “co-owners” of property rather than “joint-owners.” Property rights for Buddhist wives vary to some extent based on the type of property. Husbands and wives are entitled to one-third of: the property owned by the other spouse at the time of marriage (paryin); and property that their spouse inherited. They are entitled to equal shares of: property accumulated or increased after marriage (lathtatpwar); property gifted to the couple upon their marriage (khanwin); and property earned by both parties’ work (hnaparson). Neither spouse is entitled to property brought by the other into their union from a previous marriage (ahtatpar) (CEDAW 2007).

Under customary Buddhist law, one spouse cannot dispose of co-owned property without the other’s permission, and neither party can dispose of property through a will. Rather, co-owned property passes to a wife when her husband dies, and vice versa. The government has reported that Buddhist customary law treats parties equally in matters of inheritance, and that “there is no discrimination in inheritance for being man or woman, husband or wife, widower or widow, son or daughter, and grandson or granddaughter.” Instead, partition is decided based on the degree of relationship with the deceased benefactor. Sons and daughters are entitled to inherit equally. In the case of a polygamous marriage, the major share of property goes to the first wife and her children, and smaller amounts are apportioned successively to the other wives and children (COHRE 2007; CEDAW 2007).

As for Muslim and Hindu women, the 1898 Burma Laws Act provides that Islamic and Hindu customary laws govern matters of succession, inheritance and marriage. The succession, inheritance and marriage rights of Christians are determined by the Christian Marriage Act, the Burma Divorce Act (which applies only to Christians) and the Succession Act of 1925. The laws applicable to Christians provide very few guidelines regarding the division of property in the case of divorce, and the question is usually decided by a court based upon the reasons for divorce (Leckie and Simperingham 2009; Gutter 2001; Sen 2001).

The government has not harmonized Burma’s codified laws, which include the various religious acts governing marriage and property, with the plethora of customs practiced by various groups across the country. Many of these customs provide men greater economic and decision-making power in domestic affairs. These practices govern many women’s lives, particularly as the government is not actively present in many rural areas (WLB 2008).

Customary laws in some ethnic regions effectively discriminate against women’s rights to land. For example, in some rural areas of Shan State, the traditions of the largely Buddhist Palaung population dictate that in the case of divorce a wife loses all jointly held property. In addition, men inherit all of their parents’ property and make all decisions about the disposal of property, including the disposal of property through inheritance. Property goes to sons in the case of a husband’s death or, if he has only daughters, to his brothers (WB 2014; WLB 2008; Transnational Institute 2015).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The change in government in 2016 may lead to significant changes in the structure of land administration institutions in Burma. Currently, the MoALI is responsible for implementing national policies on agriculture. It is comprised of thirteen departments, including six that are responsible for planning, water resources, irrigation, mechanization, settlement and land records. Myanmar Agricultural Services (MAS), MoALI’s largest unit, is responsible for field operations relating to extension, research, land use, seed multiplication and plant protection. The Irrigation Department, also within MoALI, oversees all aspects of irrigation design, construction, operation and maintenance. Other major departments are the DALMS), several State Economic Enterprises, and the Agricultural University at Yezin. The DALMS oversees land management, administers the land-tax system and conducts national agricultural surveys following cropping periods. Following passage of the 2012 Farmland Law and the Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law (VFV Law) the DALMS is responsible for recording and registering interests in farmland and for issuing LUCs to farmers whose use rights have been approved by Farmland Management Body. The GAD takes the lead on management of vacant, fallow and virgin lands (Oberndorf 2012; UNDP n.d.; Saw 2014).

Both MAS and the DALMS maintain staff at state, division, district and township levels. Other MoALI departments active at the field level maintain and coordinate their presence through Agricultural Supervision Committees (ASCs) (UNDP n.d.).

The 2012 Farmland Law created the Farmland Management Body (FMB), which replaced the former Land Committee. It is comprised of officials from MoALI and DALMS. The central FMB forms FMBs at the region, state, district, township, ward and village tract levels, and delegates responsibilities to them. Delegated responsibilities include: reviewing applications for farmland use; formally recognizing and approving rights to use farmland; submitting approved farmland rights to the DALMS for registration; conducting farmland valuations for tax and compensation purposes; issuing warnings, levying penalties and rescinding use rights where use conditions are not met; and resolving disputes relating to farmland allocation and use. The central FMB provides “guidance and control” relating to: land disputes; certain transfers of land use rights; shifting taungya cultivation; allocation of alluvial land; and issuance and registration of LUCs. In addition, the central FMB revokes land-use rights under various circumstances and approves regional and state-level requests to use farmland for certain purposes, such as for housing and human settlement (Oberndorf 2012; UOB Farmland Law 2012b).

The 2012 VFV Law also created the CCVFV, a national level multi-ministerial body formed at the president’s discretion. In coordination with relevant ministries and regional and state governments, the committee oversees the granting and monitoring of use rights for virgin, vacant and fallow lands for agricultural, mining and other purposes. According to the VFV Law, the committee’s responsibilities include: receiving various ministry and lower-level government recommendations for the use of vacant, fallow and virgin land; receiving land-use applications from individuals, private investors, government entities and nongovernmental organizations; rescinding or modifying vacant, fallow and virgin land use rights; helping right holders obtain technical assistance, inputs and loans; and resolving disputes related to vacant, fallow and virgin land use in coordination with other government entities. The committee is also responsible for forming task forces and special groups at the regional and state level for scrutinizing applications for use rights; as well as special boards to determine right holder compliance with granted use rights (Oberndorf 2012; UOB Foreign Investment Law 2012c).

The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation (MoNREC) is responsible for all land designated as forest land and mining lands. There are reports of tension between MoALI and MoNREC in relation to land governance and administration responsibilities (Faxon 2015).

In July 2012, the government formed two new entities in recognition of the need to address land classification, land tenure insecurity and land-related conflict in Burma. The Land Allotment and Utilization Scrutiny Committee, a cabinet-level body in the executive branch, was focused on national land-use policy, land use planning and allocation of land for investment. It was disbanded in October 2014 and replaced with the National Land Resources Management Central Committee which continued to lead work on developing a National Land Use Policy under the leadership of MoNREC. The National Land Resources Management Central Committee was recently disbanded by the2016 Government. The Land Confiscation Inquiry Commission, subsequently renamed the Farmland Investigation Commission, was a parliamentary body within the government’s legislative branch. It investigated land disputes and whether confiscation has been carried out in compliance with the law. It commenced work in September 2012 and prepared a number of reports on unresolved land confiscations in the country that it tasked the executive branch with resolving. A new Central Review Committee on Confiscated Farmlands and Other Lands was appointed in mid-2016 to attempt to resolve land disputes and return land to dispossessed farmers. It has vowed to resolve all “land grabbing cases” within six months (Myanmar Times 2012a; Oberndorf 2012; MCRB 2015; The Irrawaddy 2016f).

Burma’s previous president appointed a National Human Rights Commission. In 2014, complaints involving land disputes were more numerous than any other category. Although the commission has indicated interest in addressing these, it is not clear that the resolution of land disputes lies within its mandate. (Displacement Solutions 2012; Human Rights Commission 2015).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

According to a 2003 report by the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation, the number of household-based agricultural landholdings in Burma grew by 20 percent between 1993 and 2003, and the total area for such holdings increased by 25 percent. From 2003 to 2010 the number of such holdings increased by 49 percent. From 2003 to 2010 the number of holdings of less than 1 acre dropped by 48 percent while holdings of 50 acres or more increased by 114 percent. As of 2010 20 percent of households controlled 69 percent of all farmland. The dramatic increase in private landholdings may be due to the expanded cultivation of “wasteland” following a 1991 directive on the management of cultivable, fallow and waste land. From 1993-2003, commercial landholdings increased by 900 percent, and the total area for those holdings increased by 325 percent.

In recent years, Burma’s government has attempted to liberalize the country’s economy and overhaul its agricultural economy, including by granting national and foreign private entities the right to use land. As of March 2013, the government had granted concessions for more than 900,000 hectares of VFV agricultural land to 377 companies (Woods 2011; Displacement Solutions 2015; Srinivas and Hlaing 2015).

The price of land in Burma has increased dramatically in recent years. Property is changing hands for well over US $1 million in urban areas, even in areas where one might find apartments without electricity or running water. Rural areas, too, are experiencing price appreciation. The increase is partly due to artificial inflation in the wake of heavy investment by Burmese who have surplus capital but lack investment options outside the real estate market. It also relates to land speculation, which has increased along with anticipation of foreign investment following the end of military rule and a period of rapid economic and political reform. High prices do not seem to have been effected by a steep drop in demand for commercial properties in urban centers (Displacement Solutions 2012; Myanmar Times 2012b; Business World 2012; Myanmar Insider 2015; Irrawaddy 2016b).