Published / Updated: May 2013

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

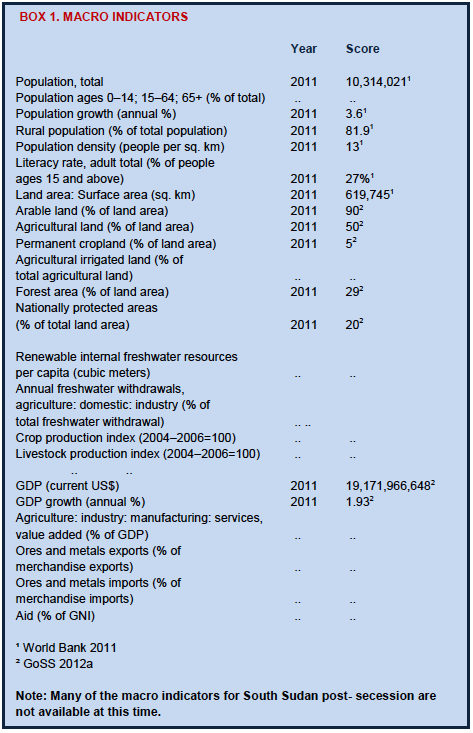

The Republic of South Sudan is the world’s newest country, covering an approximate area of 619,000 square kilometers, estimated to be one third of the total land area of Sudan. The country became independent on July 9, 2011 after two civil wars with Sudan. The wars, which spanned 50 years, have delayed development of basic infrastructure, human services such as education and health, agricultural investment and agricultural extension. Violent conflict between South Sudan and its northern neighbor over resources and revenues, as well as over cultural and religious differences, formally ended with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005. The CPA established the Government of National Unity (GNU) and the Government of South Sudan (GoSS) and supported wealth and power-sharing arrangements during a six-year interim period for peace building.

During the interim period, a fragile peace persisted even as conflict over access to resources and political control continued in the oil-producing regions straddling the North-South border. Despite constant turmoil and tension, the GoSS was able to maintain a degree of political independence that allowed it to adopt its own constitution (subject to the terms of the national 2005 Interim Constitution) and legislation, including a Land Act enacted in February 2009. In addition, with the support of foreign aid, South Sudan began to establish and develop the institutions necessary to promote economic growth and prosperity.

South Sudan is the most oil-dependent country in the world, with 97% of its revenue coming from oil. The oil reserves lay along the North-South border, and 75% of the reserves of the former country are located in the South. But South Sudan lacks the necessary infrastructure to refine, transport and ship the oil, and depends on the existing infrastructure in the North. The oil-dominated economy makes South Sudan extremely vulnerable to changes in oil prices and oil production levels, and dependent on its relationship with Sudan.

Despite South Sudan’s abundance of oil and other natural resources, its population remains poor, due in large part to the effects of protracted conflict and apparent lack of transparency and accountability to equitably distribute oil resources. The country’s 10 million people comprise over 200 tribal groups with a variety of lifestyles that depend upon crop agriculture, pastoralism and mixed crop and livestock agriculture. Some progress has been made in the interim period to address challenges facing South Sudanese. However, the country continues to respond to numerous obstacles that impede its ability to grow a diverse economy not solely dependent on oil. The GoSS has attempted to create employment opportunities, to support returning IDPs through reestablishing livelihoods and basic necessities, and to maintain a fragile peace not only with Sudan, but also among South Sudan’s diverse ethnic groups, which compete over land, water and other natural resources. The government is committed to addressing current barriers to economic development. Over the short-term, its priorities are to continue: (1) improving governance; (2) achieving rapid rural transformation to improve livelihoods and expanding employment opportunities; (3) improving and expanding education and health services; and (4) deepening peace-building efforts and improving national security.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

As a newly independent country whose development has been stalled, South Sudan’s future stability depends in part on its ability to maintain the fragile peace with Sudan. Despite South Sudan gaining 75% of the region’s oil production after independence, the country remains dependent on Sudan’s export facilities since there is no infrastructure in the South. Disputes over pipeline fees, revenue-sharing and demarcation of the contested oil fields that straddle both countries have led to violence and insecurity in the region, causing South Sudan to shut down its oil production. Although the countries have reached an agreement, tension in the region remains. Donors can assist the GoSS by supporting the adoption and implementation of the recently negotiated agreement that outlines terms for sharing of oil revenue and pipeline fees; demilitarizing the contested oil fields; and demarcating the oil fields that are located on both sides of the border.

South Sudan has made significant progress in establishing a comprehensive legal framework for land and natural resources. However, the government needs assistance in addressing chronic gaps and pressure points, establishing necessary governance bodies at all levels, and developing mechanisms for control and enforcement of rights. Donors can assist the government by supporting the enactment of draft policies and bills; clarification of rights to land held by government at all levels, communities and individuals; capacity development of the South Sudan Land Commission to make informed decisions about coordinating natural resource use among public and private entities and communities; and increased transparency of and reduced conflict over the allocation of resources to private sector investors and over the revenues generated by the extraction and use of the natural resources.

Customary law continues to govern the use of land and other natural resources in South Sudan, with each ethnic group applying its own laws relating to land and land rights within its own territory. However, customary rules are not equitable and restrict women’s access to land and property. The current legislation recognizes the importance of customary institutions as well as their inability to protect women’s access, control and ownership of land. While the legal framework provides a solid foundation, efforts need to be made to clarify roles and responsibilities of the government and customary institutions when rights overlap, and to provide guidance on how to bridge the gap between a customary framework that restricts women’s rights, and the new legal framework that puts women on equal footing with men. Donors can assist the government by: helping to develop a Community Land Act that would establish guiding principles and a legal framework for the governance of community lands by traditional and formal governing institutions; clarifying roles and responsibilities of traditional institutions and the newly mandated local land institutions such as the County Land Authorities and district-level Payam Land Councils over the governance of community lands; ensuring that women participate in the decision-making process and increasing women’s representation within land administration institutions; sensitizing government, customary institutions and communities to the importance of women’s access, control, inheritance and ownership to land; and coordinating implementation efforts to ensure regional coverage, documentation of best practices, and providing comparative knowledge about the process of integrating customary rights into formal law.

Conflicts among competing groups over access to and control over land and water are common in South Sudan, and the decades of war, prevalence of weapons and large numbers of people with combat experience have increased the likelihood of disputes turning violent. Establishment of an effective, integrated, socially legitimate system for the resolution of disputes over land and other natural resources is critical to South Sudan’s future. Donors can assist the government in assessing the actual and potential roles played by traditional authorities on one hand, and formal legal institutions and forums on the other. Donors could further help the GoSS to develop options for creating a system that more fully integrates formal and customary components and supports local governance bodies in their implementation of laws and policies.

Rapid urbanization across South Sudan has outpaced the capacity of government institutions to create and implement master plans and develop policies for upgrading and regularizing informal settlements. Donors can assist the GoSS in: developing appropriate strategies for urban planning and settlement upgrading; identifying resettlement trends and regional needs to accommodate returning IDPs; and providing technical assistance to help draft and implement legislation and programs to regularize informal rights, paying particular attention to vulnerable groups such as IDPs, households affected by HIV/AIDS and households headed by women and children.

Summary

South Sudan, with a land area of 619,745 square kilometers, has an abundance of water, forest and mineral resources. The River Nile is the dominant geographic feature in South Sudan, which is also home to Africa’s second-largest wetlands, the Sudd, and the largest intact savanna ecosystem in East Africa. South Sudan’s swamps, floodplains and grasslands contain a rich biodiversity of flora and fauna.

South Sudan, with a land area of 619,745 square kilometers, has an abundance of water, forest and mineral resources. The River Nile is the dominant geographic feature in South Sudan, which is also home to Africa’s second-largest wetlands, the Sudd, and the largest intact savanna ecosystem in East Africa. South Sudan’s swamps, floodplains and grasslands contain a rich biodiversity of flora and fauna.

The country is made up of 10 states sparsely populated by roughly 10 million people. An additional two to three million South Sudanese are estimated to live in Sudan or other neighboring countries, or further abroad. There are also an estimated 390,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in South Sudan, informally settled in urban areas or on land provided by host communities. Although many parts of South Sudan remain peaceful, there is often conflict among communities that share resources such as water points, grazing lands and agricultural land. For the majority of South Sudanese, access to land and water is and will continue to be important for livelihood, since over three-quarters of the population relies on farming, pastoralism or a mix of both.

Customary law, specific to each ethnic group, has governed the use of land and other natural resources in the region for centuries. Formal land laws have had little impact on the customary tenure system in South Sudan. However, with the signing of the CPA, the GoSS recognized the need for legislation, policy and formal institutions to ensure that land rights are equitable for all South Sudanese. The CPA mandated the establishment of the South Sudan Land Commission (SSLC), which has begun to develop land policies that reflect customary rules and institutions, per the Interim (2005) and Transitional (2011) constitutions. Three laws – the Land Act (2009), the Local Government Act (2009) and Investment Protection Act (2009) – provide a statutory framework for fair and transparent administration of land rights in South Sudan. The Land Act classifies land as public, community or private and provides that the land is owned by the people, and that the government regulates land use.

In the absence of a clear and enforceable legal and regulatory framework for land transactions, foreign investors have recently acquired large areas of land in South Sudan. The GoSS transferred an estimated 5 million hectares of land – including all 2,280,000 hectares of the Boma National Park – to private companies in long-term leases during the interim period.

Forests and woodlands make up nearly a third of South Sudan’s land area, and 20% of the country’s land is designated as forest reserves. Forest timber and non-timber resources are used for food, timber, firewood and habitat and supply 80% of the county’s energy. In addition, forests provide the country with economic opportunities. South Sudan formally and informally exports a wide range of timber products to international markets; however, the sector is poorly managed, and reliable numbers quantifying exports and economic potential do not exist. Many non-timber forest products such as shea nuts, gum arabic and honey are harvested for local consumption. There is growing international demand for non-timber products, in particular shea nuts and gum arabic. But South Sudanese have not been able to benefit from these natural resources due to insignificant investments by the government to improve the sector.

South Sudan has significant oil and gas reserves as well as deposits of gold, silver, chrome, copper, iron, manganese, asbestos, gypsum, mica, limestone, marble and uranium. Upon independence, South Sudan gained ownership of 75% of Sudan’s oil production since the majority of reserves are located within the boundaries of the South. However, the pipelines, refining and export infrastructure are located in the North, making South Sudan dependent on Sudan to export the oil to market. The CPA outlined the management of the oil and sharing of the revenue during the interim period, but did not address ownership of fields straddling the border. In addition, the CPA included a new revenue-sharing formula and new payment requirements for the use of Sudan’s export infrastructure by South Sudan after South Sudan’s secession. This resulted in a dispute over revenue-sharing and pipeline fees between the two countries, prompting South Sudan to shut down its oil production. In 2012, the countries reached an oil revenue-sharing agreement that should allow oil production to commence.

Land

LAND USE

South Sudan’s total land area is 619,745 square kilometers, of which more than half is estimated to be suitable for agriculture. In addition, South Sudan has the second-largest wetlands in Africa and the largest intact savanna ecosystem in East Africa. Natural forests and woodlands cover 29% of the total land area. Based on a number of studies from 1973 to 2007, the average annual rate of deforestation was approximately two percent. There are currently six national parks and 13 game reserves in South Sudan, covering 11% of the land area (90,755 square kilometers) (UNDP 2012a; GoSS 2011a; GoSS 2011b; GoSS 2011c; FAO 2010).

South Sudan includes 10 states and a population of about 10.3 million people made up of 200 ethnic groups. Approximately 78% of all households earn their livelihood from farming, pastoralism or a mix of both. Farming is predominantly rainfed, and farmers cultivate their small plots with handheld tools. Some common agricultural products include pineapple, cotton, groundnuts, sorghum, millet, wheat, cotton, sweet potatoes, mangoes, pawpaw, sugarcane, cassava and sesame. Pastoralists hold approximately 8 million cattle in aggregate and, in addition, there are millions of poultry, goats, pigs, horses, donkeys and sheep. Sedentary farming is on the rise in South Sudan, which has reduced the amount of grazing land available for pastoralists (Ghougassian 2012; GoSS 2011a; World Bank 2010a; USAID 2010a; FAO 2010).

In 2011, South Sudan had an estimated GDP of $19.17 billion ($1859 per capita). The GoSS determined the most recent GNI figure of eight billion dollars ($984 per capita) in 2010. Oil exports accounted for 71% of the total GDP in 2010 (World Bank 2012; GoSS 2011d).

A number of environmental concerns threaten South Sudan’s natural resource base. The most critical may concern the country’s water resources: the water level of rivers is decreasing and streams are drying up due to upstream land-use changes and environmentally unsound water management interventions, such as forest clearing, dams, over-grazing and fires resulting in increased evaporation and decreased infiltration.

Additionally, rainfall is irregular due to seasonal fluctuations, climate change and local environmental changes. Soil and habitat degradation are also on the rise. Due to unsustainable agriculture and poor bush-fire management, soil degradation is becoming more severe and is leading to decreased ecosystem functions and competition over land and water resources; habitats are degrading and fragmenting due to increasing livestock grazing as well as expanding agriculture. Pollution is another serious concern, as soil, air and water pollution increases due to industrial, residential and agricultural practices that do not mitigate negative environmental impacts (including pollution of rivers by discharge of wastewater, solid waste, oil and other pollutants). Pollution of particular places, such as the Sudd wetlands, has worsened due to oil exploration. Natural resources (e.g., timber, charcoal, water, land, etc.) are being increasingly depleted due to unsustainable land-use practices resulting from population increase and resettlement. Forests are being cleared for large-scale agricultural projects on land that has been privatized by the government, and biodiversity is declining due to habitat degradation and increased illegal exploitation and poaching of wild animals (Ghougassian 2012; UNDP 2012b).

Finally, economic opportunities in South Sudan are limited due to poor transport infrastructure (roads, bridges and railway networks) and inadequate electricity. The country lacks roads linking major towns, feeder road networks between rural communities, and proper maintenance for all roads. This has contributed to: the slow economic growth and development of rural and peri-urban communities; prevented people from connecting to markets; imposed high transportation costs on traders and farmers that choose to carry products to markets, and; inhibited people’s ability to access basic social services like health and education. Similar to poor transport infrastructure, inadequate electricity has become a serious constraint on economic development. The absence of reliable power has placed restrictions on: irrigation systems that would increase agricultural production; the value chain of products that require cool storage units such as produce and medications, and; agro-processing operations that make agricultural products useable (GoSS 2011f).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

South Sudan encompasses a large area which, at first glance, appears sparsely populated. Estimated population density is only 30 people per square kilometer, and vast swaths of land appear unsettled or unused. However, unsettled land is not necessarily unclaimed land, and much of the region’s land is subject to customary claims by the numerous and varied communities throughout South Sudan. Chiefs and other traditional authorities retain significant control over land allocation, use and claims. Besides its importance as a resource and source of livelihood, land is endowed with cultural and spiritual significance, and is closely linked to the history, traditions and social relations of many of South Sudan’s people (GoSS 2011f).

The civil war and natural disasters have resulted in widespread destruction, displacement of peoples and the deterioration of effective governance, all of which have contributed to conflict and weaknesses in the administration of land rights. Approximately 390,000 IDPs live in South Sudan, informally settled in urban areas or on land provided by host communities. Many IDPs attempting to return to their areas of origin have found their land occupied, even as some host communities complain that IDPs must vacate land and return to their own areas. In other locations, some populations have been welcoming to IDPs, but do not afford them the same land rights. Institutions and procedures for restituting land, paying compensation for lost land or facilitating integration into host communities, are absent or inadequate for resolving land conflicts (GoSS 2011f).

The capital of South Sudan, Juba, and other urban centers are rapidly growing in population and experiencing rapidly intensifying economic activity. After the signing of the CPA, aid actors and private sector investors, most of who are economic migrants flooded Juba and the other state capitals to support the new interim national and state governments. The new investments also triggered the need for small businesses, merchants and additional unskilled labor. Recent immigrants to the city comprise a diverse range of people – returning residents, previous IDPs and many newcomers, including foreigners – in search of security, better livelihoods and business opportunities. Since the 2008 census, Juba’s population has doubled from 300,000 to 600,000, making it the fastest growing city in Africa. The expansion of Juba has been unplanned and for the most part unregulated, creating two urban dichotomies. The first consists of an estimated 700 NGOs and 8000 businesses that primarily cater to the development workers and private sector investors. As Juba grows, this sector of the economy will continue to thrive. The second is made up of the urban poor who lack the financial capital, skills and education to access the international economy (USCC 2011; Martin and Mosel 2011).

Juba has been the seat of government since the signing of the interim constitution in 2005. However, Juba is also the state capital of Central Equatoria State, whose population is predominantly comprised of the Bari ethnic group. As the city expands, Bari leaders have expressed concerns that the city is growing into surrounding villages without their permission. The GoSS and the Bari leaders have been unable to agree on terms for Juba’s expansion, and the GoSS is currently considering proposals to relocate the capital. A ministerial committee that was formed to find a more suitable location identified Ramciel in Lakes State as a possible option. Ramciel is considered the geographic center of South Sudan, touching all three major regions of the country – Greater Upper Nile, Greater Equatoria and Greater Bahr el Ghazal (Sudan Tribune 2011a; Gurtong 2011).

South Sudan’s oil reserves, the third-largest in Africa, are primarily located along its northern border in the Abyei region and were never defined or demarcated under the CPA. The area remains contested between South Sudan and Sudan, and conflict and fighting continue over the disputed zone (Sanders 2012; USCC 2011).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

As part of the peace process, Sudan and South Sudan recognized the need to develop land policy, legislation, functioning institutions and supporting services, and so included institutional and governance mechanisms into the CPA. The CPA mandated the establishment of the National Land Commission (NLC) and the South Sudan Land Commission (SSLC) to develop land policies and draft legislation to clarify and strengthen land administrative systems and the rights of landholders. The Transitional Constitution of 2011 states that all land in South Sudan is owned by the people of South Sudan, and charges the government with regulating land tenure, land use and exercise of rights to land. The constitution classifies land as public, community or private land, and requires the GoSS to recognize customary land rights when exercising the government’s rights to land and other natural resources. The constitution does not clarify the extent to which customary rights can limit government’s rights, but does require that all levels of government incorporate customary rights and practices into their policies and strategies. As a result, the Land Act (2009), the Local Government Act (2009) and the Investment Promotion Act (2009) were developed to establish the institutions and mechanisms of governance that would address pressure points and fill vacuums created by conflict, uneven development and lack of transparency and accountability in resource governance (GoSS 2011f; GoSS 2011g).

The three laws establish the fundamental framework for the fair and transparent administration of land rights in South Sudan. The Land Act regulates land tenure and equally recognizes rights to customary, public and private tenure. The Local Government Act defines primary responsibilities of local government and traditional government authorities in the regulation and management of land, which includes charging customary institutions with particular responsibilities for administering community land rights. The Investment Promotion Act establishes procedures for facilitating access to land for private investment, including by foreign investors, in ways that balance the interests of both current right holders and investors. Although a framework has been developed, government officials have a poor understanding of the laws and lack the capacity to interpret and carry them out. There is also a lack of awareness by the population as a whole, which further impedes progress (GoSS 2011e; GoSS 2011g).

The SSLC also developed a draft Land Policy that strengthens the rights of land holders, communities and citizens within the new framework and guidelines established by the Land Act (2009). It emphasizes the importance of access to land as a “social right,” a feature of many customary land tenure systems that allows community members to access land irrespective of wealth or economic status (Deng and Mittal 2011).

Customary law has governed the use of land in South Sudan for centuries, with each ethnic group applying its own laws relating to land and land rights within its own territory. Land laws enacted by governments in Khartoum throughout the colonial and post-colonial periods do not appear to have seriously affected customary tenure systems in the South. Thus, on the whole, customary laws and practices remain largely intact. Although they vary from community to community, customary institutions and traditional mechanisms continue to govern the access, use and allocation of land (USAID 2010b).

With the signing of CPA and enacting of the constitution, the Land Act, Local Government Act and Investment Promotion Act, South Sudan, for the first time in history, has written laws that give prominence to customs and traditions, and recognize the rights of the indigenous communities to land. But while the new government has now officially recognized indigenous and customary systems of land administration, its simultaneous encoding of overlapping rights has created some confusion. Currently, there is a lack of clarity regarding the proper roles and responsibilities of the GoSS and state and local governments in the administration of land law. The constitution stipulates that all land in South Sudan is owned by the people of South Sudan and held in trust by the government. The Land Act echoes the spirit of the constitution but does not, for example, specify which level of government controls public land in any given area. This lack of clarity creates ambiguity over the roles of government at each level, which leads to encroachment by the different levels of government over one another’s jurisdiction and causes confusion among communities when authorities exercise their powers. However, all parties understand the importance of developing clear policies and laws to govern relations between the different levels of governments and between formal government and traditional institutions in order to have a well-functioning land management system (USAID 2010b).

TENURE TYPES

The 2009 Land Act states that all land is owned by the people of South Sudan, and the government is responsible for regulating use of the land. The Land Act classifies land as public, community or private land. Public land is land owned collectively by the people of South Sudan and held in trust by the government. Public land includes land used by government offices, roads, rivers and lakes for which no customary ownership is established, and land acquired for public use or investment. Community land is land held, managed or used by communities based on ethnicity, residence or interest. Community land can include land registered in the name of a community, land transferred to a specific community and land held, managed or used by a community. Private land is the final classification and is considered by law to be registered freehold land, leasehold land and any other land declared by law as private land (GoSS 2009a).

The Land Act recognizes three tenure types: customary, freehold and leasehold. Land used for residences, agriculture, forestry and grazing can be held under customary tenure. Customary land rights are inheritable and can be subject to usufruct rights and sharecropper agreements, but cannot be permanently alienated. Traditional authorities may allocate lifetime tenure rights to customary land. However, if a parcel is non-residential and exceeds 250 feddans (about 105 hectares), traditional authorities must notify local government and secure their approval in advance of making any transfer. Freehold rights are held in perpetuity and include the right to transfer the land temporarily or permanently. The Land Law does not state how freehold rights are acquired. Leaseholds can be obtained for customary and freehold land, and can be granted for up to 99 years. Leases of more than 105 hectares of customary land must be approved by two local government bodies. Foreigners cannot own land in South Sudan, but can lease land for periods up to 99 years (GoSS 2009a; Rolandsen 2009).

The draft Land Policy, currently under review, clarifies some ambiguities in the Land Act by endorsing in general terms the existing patterns of land tenure as they relate to land use, as follows: (1) community tenure will be the principal form of tenure in areas that are predominantly rural; (2) public and freehold tenure will be the principal forms of tenure in areas that are officially gazetted as urban areas under the Town and Country Planning Act; (3) public land also includes land over which no private ownership (including customary ownership) is established, roads and other public transportation thoroughfares, water courses over which community ownership cannot be established and forest and wildlife areas formally gazetted as national reserves or parks; and 4) peri-urban areas may be held under community, public or private tenure (GoSS 2011f).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Both the Land Act and draft Land Policy provide for the registration of land in South Sudan. The Land Act states that all land, whether held individually or collectively, shall be registered and granted a title. Systematic registration shall take place at the request of the state and be carried out by the Ministry of Housing, Physical Planning and Environment. Communities can register their land in the name of the community, in the name of a traditional leader as trustee for the community or in the name of a clan, family or community association. Once community land is registered, individual members of the community may be entitled to register individual rights to land within the community land area (GoSS 2011f; GoSS 2009a).

The Land Act indicates the importance of customary authority and mandates the establishment of County Land Authorities and district-level Payam Land Councils. Land Authorities and Councils are local land institutions comprised of county and district level representatives entrusted to act as civic authorities and administrators over community land. The composition of the county level bodies is as follows: one representative from each town and municipal council; one representative from the Ministry of Housing, Physical Planning and Environment appointed by the Minister; a representative of traditional authority; one representative of civil society; and, one woman representative recommended by the County Women Association. State Governors will appoint individuals to the Land Authorities based on recommendations from County Commissioners. Land Authorities’ responsibilities include: holding and allocating public lands on behalf of local government; making recommendations on gazetted land planning; advising on resettlement of IDPs; facilitating the registration and transfer of land; supporting cadastral operations and surveys; advising local communities on land tenure, usage and exercise of rights; and coordinating with the SSLC and other government bodies. The Payam Land Councils are responsible for the management and administration of land at the district level. Districts are comprised of subsections called bomas. Members of each Payam Land Council will be appointed by the State Minister based on recommendations from County Commissioners and in consultation with the traditional authority in the payams. Payam Land Councils are composed of: the executive chief of each boma and a representative from the Farmers and Herders Association, representatives of a civil society group and one woman recommended by the payam Women’s Association (GoSS 2011f; GoSS 2009a).

The Land Act indicates the importance of customary authority and mandates the establishment of County Land Authorities and district-level Payam Land Councils. Land Authorities and Councils are local land institutions comprised of county and district level representatives entrusted to act as civic authorities and administrators over community land. The composition of the county level bodies is as follows: one representative from each town and municipal council; one representative from the Ministry of Housing, Physical Planning and Environment appointed by the Minister; a representative of traditional authority; one representative of civil society; and, one woman representative recommended by the County Women Association. State Governors will appoint individuals to the Land Authorities based on recommendations from County Commissioners. Land Authorities’ responsibilities include: holding and allocating public lands on behalf of local government; making recommendations on gazetted land planning; advising on resettlement of IDPs; facilitating the registration and transfer of land; supporting cadastral operations and surveys; advising local communities on land tenure, usage and exercise of rights; and coordinating with the SSLC and other government bodies. The Payam Land Councils are responsible for the management and administration of land at the district level. Districts are comprised of subsections called bomas. Members of each Payam Land Council will be appointed by the State Minister based on recommendations from County Commissioners and in consultation with the traditional authority in the payams. Payam Land Councils are composed of: the executive chief of each boma and a representative from the Farmers and Herders Association, representatives of a civil society group and one woman recommended by the payam Women’s Association (GoSS 2011f; GoSS 2009a).

Although the Land Act mandates the establishment of local land institutions, there are no clear procedures for establishing land authorities or councils and, as a result, very few have been created. Although the draft Land Policy does not provide additional guidance, it does recommend the development of a Community Land Act that would establish guiding principles and a legal framework for the governance of community lands by traditional and formal governing institutions (GoSS 2011f; GoSS 2009a).

The Land Act and draft Land Policy recognize the importance of, and aim to facilitate, the resettlement and reintegration of IDPs, refugees and other categories of persons whose rights to land were affected by the civil war. Moreover, the Land Act grants a right of restitution if a landholder lost his or her land rights (formal or customary) after being involuntarily displaced as a result of the 1983 civil war. The right of restitution exists regardless of whether the land was taken over by an individual or by the government, and extends to family members, legal heirs and any other person who had an interest in the land at the time it was lost. According to the Land Act, claims for restitution must have been filed to traditional authorities or the South Sudan Land Commission (SSLC) within three years of the enactment of the Land Act (i.e., by January 2012). The Land Act provides for monetary compensation to the claimant in the event that the government cannot provide land. It is not clear how many claims have been filed with either traditional authorities or the SSLC, and the current status of such claims is unknown; however, once adopted, the draft Land Policy would extend the restitution period in acknowledgment of the fact that people are unaware of their restitution rights and the associated timeline (GoSS 2011f; USAID 2010b; GoSS 2009a).

Under the Land Act and draft Land Policy, the GoSS cannot force IDPs and returnees to return to their ancestral homes. And both the law and the draft policy lack formalized rules to resettle or compensate returnees. Despite the absence of a structured framework, in some areas local management systems have been flexible and have absorbed returning community members. Many repatriated South Sudanese choose to stay in Juba and other commercial towns, where their presence puts increased pressure on resources and assets such as land, and formal land administration systems are failing to cope with the influx of people. The lack of a clear policy and legal framework, and limited institutional capacity in both rural and urban areas compounds the challenge of resettling returnees and IDPs in South Sudan (USAID 2010b; USAID 2010c).

INTRA HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

The Transitional Constitution, Land Act and draft Land Policy recognize that the right to land shall not be denied to any citizen by the GoSS, State Government or community on the basis of sex, ethnicity or religion. In addition, the Constitution stipulates that women have the right to own and inherit land, together with any surviving legal heir or heirs of the deceased. However, despite the legal framework’s incorporation of language that protects women and other vulnerable groups, the key legislation governing statutory land tenure still contains openings for discrimination For example, the Land Act provides for one slot in each Land Country Authority and payam Land Authority to be allocated to a woman. But these provisions do not meet the threshold envisaged in the constitution that 25% of seats in government bodies be filled by women. When it comes to the issue of succession and inheritance, there is currently no legislation to help operationalize those sections in the Constitution that provide for women’s right to own property and share in the estate of deceased husbands (together with any surviving heir of the deceased). The provision is ambiguous and does not explicitly provide for daughters’ rights in the estate of a deceased father (GoSS 2011f; GoSS 2009a; USAID 2012a).

The customary land tenure system in South Sudan limits women’s access, control and ownership of land. Knowledge, recognition and protection of women’s rights remain limited throughout South Sudan because most men and women are not aware of the rights of women in accessing land. But when men and women are aware, they often claim that cultural and traditional norms should override any legal provisions. Women generally do not own or inherit land in South Sudan. They typically access land only through their husbands, and may lose this access if widowed. Even where traditional institutions are willing to allocate land to women, most customary laws do not consider women equal to men, and this limits how women can hold rights to land. Thus, women’s land rights remain largely conditional, derived through their marital or childbearing status, or guaranteed through other male relatives. It is also common for widows, daughters and divorced women to be dispossessed of their land rights. For example, in some communities, a widow can be forced to leave her marital land following the death of her husband, or, male relatives can deny daughters inheritance of family lands. While some argue that customary rules and practices should adapt to changing social circumstances, others resist change, fearing its impact on tradition and cultural identity. These competing notions lead to a significant gap between the law and practice, particularly in rural areas (GoSS 2011f; USAID 2010b; GoSS 2009a; USAID 2012a).

Historically, customary systems for land and property rights incorporated important safeguards for women’s access to land, and family and marriage customs generally protected the access rights of older women and widows. With the conclusion of the civil war, however, a large number of women (mostly younger) are returning to their ancestral homes. An estimated 45–50% of these women are returning as heads of their households, since many men died during the conflict with Sudan. Rights for younger women are traditionally weaker, and customary institutions are ill-equipped to deal with the fact that younger women have increasingly become heads of households. Issues of women’s access to land and property rights have thus become more contentious in both rural and urban communities (USAID 2010b).

The issue of women’s access to land and property rights needs to be addressed in the context of prevailing customary tenure practices as well as within the context of provisions in the South Sudan Transitional Constitution that establish women’s equal rights to land and property. Generally, there seems to be a consensus among government authorities that women’s rights to access, inherit and own land is a significant issue that should be addressed. But efforts to strengthen women’s land and property rights remain a challenge due to difficulties in bridging the gap between traditional authorities, who prefer to govern women’s access to land within a customary framework that restricts these rights, and proponents of the new legal framework that puts women on equal footing with men (USAID 2010b).

LAND ADMINISTRATIONS AND INSTITUTIONS

The CPA stipulated the establishment of land commissions for Sudan and South Sudan (the National Land Commission and South Sudan Land Commission, respectively) that would be responsible for establishing land policy within their respective jurisdictions. The Land Commissions were intended to: enforce land law; resolve land disputes; assess compensation claims arising from government acquisition of land; study and record land-use practices in areas where natural resource development occurs; and conduct hearings on issues related to land and natural resources. (UNDP 2005).

Since its origin in 2006, the South Sudan Land Commission (SSLC) has made progress despite being hampered by lack of sufficient staff, funding and capacity. The SSLC, with the support of bilateral and multilateral donors, developed the Land Act (2009), and also developed the draft Land Policy that is currently under review by the GoSS. In addition, the SSLC collaborates closely with other institutions that are developing new land administration systems and laws. These include the Ministry of Legal Affairs and Constitutional Development (MOLACD) and the Land Policy Steering Committee which is made up of 13 ministries, commissions and boards (UNMIS 2010; Giampaoli 2010; USAID 2009; Rolandsen 2009; Pantuliano 2007).

The Land Act established the land registry within the Ministry of Housing, Physical Planning and Development at the national level, with coordinated registries maintained at the state level. The Land Act outlines a decentralized plan for land administration in South Sudan, with County Land Authorities and Payam Land Councils operating at county and local levels. The County Land Authority is responsible for: managing and allocating public land; resettling people in the county; registering and transferring land; supporting cadastral operations and surveying; liaising with traditional authorities; advising local communities on land rights issue; and liaising with the SSLC. The Payam Land Council is responsible for: allocating public land; land planning and demarcation; supporting land registration and transfer; protecting the customary rights of communities (including those pertaining to communal grazing land, forests and water resources); maintaining sanitation and hygiene; and assisting the traditional authorities with land management, land dispute resolution and environmental protection (GoSS 2009a).

Historically, the people of South Sudan had never had a centralized system of governance. The control and management of land was dictated by traditional leaders exercising both judicial and administrative functions. Although the Land Act provides a governance framework, it does not outline roles and responsibilities of land administrations and institutions in great depth. Clear distinctions between the respective roles of formal and customary institutions in allocating and governing community lands are particularly lacking. As a result, traditional authorities still apply customary laws within their jurisdictions, but, in doing so, encroach upon the authority of other levels of government. This overlap and the attendant ambiguity have reduced the efficiency and effectiveness of land institutions in the country. The draft Land Policy identifies some of the Land Act’s shortcomings, but it does not provide detailed guidance or procedures for clarifying ambiguities in the land management structure. Instead, the draft Land Policy broadly defines institutional roles for the various levels of government (e.g., the GoSS, the SSLC, state government, County Land Authorities and Payam Land Councils, customary authorities and civil society organizations) and outlines areas that require support and clarity. The challenges arising from overlapping mandates have also been compounded by a lack of coordination, poorly conceived strategies and work plans, and the lack of sufficient capital to address human resource constraints (GoSS 2011f; USAID 2010b).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

The Land Act prohibits foreigners from purchasing land but allows foreigners to lease land for up to 99 years. The Land Act and draft Land Policy do create a framework that allows customary land to be leased on various terms, with the community or individual community member retaining underlying land rights. The Land Act states that citizens and foreigners can obtain access to land for investment purposes and allows for states to prepare land-use plans that delineate zones; however, the Land Act is not clear about the applicability of the investment provisions to community land. Land-use plans must be filed with the South Sudan Investment Authority, which was established under the Investment Protection Act, and is charged with encouraging private investment and working with entrepreneurs (GoSS 2011f; GoSS 2009a).

Access to land is still a limiting factor for private-sector development. Even though a basic statutory framework has been established, a number of land administration matters require attention: a new cadastral system must be developed; a large area of land in South Sudan must be surveyed and mapped; the demarcation of land of country and state boundaries must be improved; and a system for the registration and titling of land needs to be developed. A prerequisite to these reforms, however, will be well-functioning and capable institutions that are able to develop and implement the land policy and legal framework. Unless, and until, the government addresses institutional defects in land governance and administration, the flow of investment is expected to be slow and ineffective (USAID 2010b; Clingendael 2009).

Inadequacies in the institutional and statutory framework for land governance have not prevented some foreign investors from acquiring large areas of land. Experts estimate that roughly 5 million hectares of land had already been committed to investors in biofuels, ecotourism, agriculture and forestry in the four years leading up to the January 2011 referendum on independence. The largest land deal to date is the Al Ain Wildlife investment by an Emirati Company that has reportedly leased all 2,280,000 hectares (22,800 square kilometers) of Boma National Park. The second-largest is by Nile Trading and Development, a US company that has reportedly leased 600,000 hectares (6000 square kilometers) of land in Lainya County from Mukaya Payam Cooperative, with rights to extend its landholding to 1,000,000 hectares (10,000 square kilometers). The third-largest is by Jarch Management, a US investment firm that has reportedly leased 400,000 hectares (4000 square kilometers) from a Sudanese company called Leac for Agriculture, Ltd. (Rhode 2011; IRIN 2011; Deng 2011).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY BY GOVERNMENT

The 2009 Land Act, the draft Land Policy and the 2009 Local Government Act establish a basic legal framework to address compulsory acquisition of private property by the government. The framework includes consulting with local communities (GoSS 2011f; GoSS 2009a).

Under the Land Act, the GoSS, state governments and any other public authority may expropriate land for public purposes, subject to the payment of compensation and upon agreement as prescribed by the Act or any other law. The GoSS may propose to take, reserve or reallocate land for a range of public uses, including the establishment of national parks, forest reserves, military installations and rights-of-way. The government’s power of expropriation is restricted to securing land for public use only, and not for subsequent transfer or sale to private individuals. Government officials are required to provide clear public explanations when they exercise their authority to restrict or remove private or customary rights in land (GoSS 2011f; GoSS 2009a).

According to the Act, the procedure for expropriation shall be based on a consultative process with the communities or individuals concerned, prior to development of the expropriation plan. As with declarations that render land ‘public,’ any expropriation for investment purposes must be preceded by the government’s provision to the public and all concerned rights holders of a clear justification for its actions. In addition to consulting the communities that own the land in question, the Land Act also requires that government officials and company representatives consult pastoralist groups with secondary rights of access before making any decision that would affect their grazing rights (GoSS 2011f; GoSS 2009a).

But South Sudan’s current land framework for governing large-scale land acquisitions lacks clear jurisdictional roles for public institutions at all levels, including an appropriate balance between central oversight and state-level flexibility, and does not provide a role for the legislative branch in approving large-scale land allocations. Due to this legal ambiguity, there is currently no uniform procedure for managing large-scale land acquisitions. Applications for land are managed through ad hoc procedures at various levels of government, contributing to a lack of transparency and accountability with regard to many deals (Deng 2011; Rhode 2011; IRIN 2011).

In general, community consultations are deficient – and in many cases entirely absent – in the context of land investments. Tensions around large-scale land deals are particularly high in and near Juba and other large towns of South Sudan, which are experiencing high numbers of returnees and IDPs seeking to settle. Recent estimates put the number of returnees and IDPs to South Sudan at 89,315 and 120,715 respectively. Community leaders in both areas have reported concerns with the management and administration of the Nile Trading and Development and the Jarch Management deals. The Nile Trading and Development deal is being challenged by Mukaya payam’s local leaders, who claim that the community was not consulted. In addition, local leaders accuse the Mukaya payam Cooperative of not representing the community’s interests, since it is made up of influential Southern Sudanese who do not live in Mukaya payam. On behalf of their community, payam leaders submitted a petition to the government requesting that the lease agreement between Nile Trading and Development and the Mukaya payam Cooperative be disavowed. Similar concerns are being raised by authorities in Mayom County, where the Jarch Management deal is located. The County Commissioner reports that he has not heard of Jarch Management. Under the appropriate procedures, the County Commissioner of Mayom County is responsible for facilitating the required consultations with the local community (Deng 2011; Rhode 2011; IRIN 2011).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICT

The signing of the CPA in 2005 ended over two decades of conflict between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A). The war was mainly fought over political self-determination, unequal development, and control over the country’s resources, especially oil and land. The physical security situation in South Sudan significantly improved after the signing of the CPA in 2005, but is still far from stable. Insecurity of rights to land and natural resources, un-demarcated borders and issues of transparency in the oil sector have caused continued friction (Clingendael 2009).

Conflicts among rural communities in South Sudan are usually resource-based. Such conflicts occur over access to resources like water points and grazing lands. These normally occur among pastoralist groups and between pastoralists and farmers. They are also evident among agro-pastoralist communities, many of which are relatively powerful groups seeking to expand into areas currently used by others (USAID 2010b).

The Land Act addresses land-dispute settlement, but has a high level of ambiguity regarding the management of dispute-resolution mechanisms by customary and government institutions. The draft Land Policy does not clarify discrepancies, but calls for strategies that will build the capacity of the institutions to peacefully mediate land disputes. Due to the lack of clear rules and regulations, the current legal framework is under-enforced, posing a number of challenges for both formal and informal institutions charged with mediating disputes. Conflicts over control of grazing land and natural resources continue between different resource users in all areas of the country. In recent years, clashes have intensified. The major conflicts in the area are: (1) between farmers and pastoralists; (2) within agro-pastoralists communities, as relatively powerful groups expand land areas at the expense of others; (3) between farmers and groups exploiting natural resources such as timber, palm trees and gum arabic; and (4) between returnees and laborers or sharecroppers on mechanized farms. The decades of war, and the high number of people with combat experience, military training and access to modern weapons have increased the deadliness of local conflict. Uniforms and weapons cause confusion regarding whether combatants are military personnel or civilians. A perception of the lack of police protection, and a lowered threshold for resorting to violence have led some communities to create armed protection details or resort to other types of self-help and vigilantism (Rolandsen 2009; Pantuliano 2007; IRIN 2008).

An increasing source of tension between communities and government institutions is the desire of foreign investors, mostly land speculators to acquire land for future agricultural investment. Traditional leaders have questioned the government’s authority to use eminent domain when allocating land to investors. Unless the government is better able to prioritize the development needs of local populations, observers opine that land investments may become a source of increasing social unrest and conflict (Deng and Mittal 2011).

After Uganda dislodged the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in 2002, the rebels exported their activities (recruitment of children, rape, killing, maiming and sexual slavery) to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and South Sudan. In South Sudan, the LRA’s presence, primarily in the state of Western Equatoria, led to competition over land and water resources in areas that had not previously been affected by the insecurity. The conflicts were mainly between farmers and displaced pastoralists over farming and grazing land, affecting the ability of local communities to sustain their livelihoods. Although there have been no reported attacks in South Sudan in 2012, communities remain vulnerable to attack by the LRA (UN News Centre 2012; Global Centre 2012; BBC 2010; NORAD 2005).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The GoSS has made significant progress toward putting policies in place that will foster economic development. To resolve ambiguities and bolster the newly established legal framework, the GoSS has put forth an aggressive agenda. By 2013, the GoSS aims to develop, distribute and implement the draft Land Policy and respective legislation to address inadequacies in the 2009 Land Act. In addition, the GoSS seeks to establish and ensure that a tested and proven set of systems and processes for transparent land administration are in place, ready for replication, continued adaptation and scaling up that will include: (1) drafting state-level implementing regulations to clarify and define the roles and responsibilities of land-governance entities in rural areas; (2) piloting regulations through the establishment and operation of at least two County Land Authority in Western Equatoria and Jonglei States; (3) building the capacity of state and county level land authorities to manage pasturelands and other common property resources; and (4) developing an inventory system for securing rights to cropland in the green belt of Western Equatoria (LANDac 2012; GoSS 2011e), and land use planning in Jonglei State.

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID has provided extensive support since independence, focusing particularly on land issues. The Sudan Property Rights Program (SPRP, September 2008–February 2011) assisted the GoSS to develop a draft Land Policy based on extensive public consultation and research, and provided support to build the capacity of the South Sudan Land Commission (SSLC). The SPRP concluded in February 2011 with the handover to GoSS of a draft Land Policy which is undergoing a final high-level review before promulgation. In 2010, the SPRP and SSLC concluded a series of government and civil society stakeholder consultations that directly involved over 1000 key GoSS, state and local government and civil society stakeholders as well as traditional leaders. Complementing the consultations, the SPRP and the Nile Institute of Strategic Development and Policy Studies (NISPDS, based at Juba University) managed a research project on key land-tenure and property-rights issues such as conflict, urban informal settlements and jurisdiction for land administration. These research findings informed the drafting of the Land Policy. Finally, the SPRP convened training in Juba for sixty-four GoSS, state and local government participants on land-tenure and property-rights concepts and practices, presented by regional and international experts (USAID 2011a).

A follow-on project, the Sudan Rural Land Governance Project (SRLG, 2011–2014) will help harmonize the draft Land Policy with the 2009 Land Act and support selected state and local governments for more effective land administration and planning. This will be accomplished by helping the GoSS to develop and refine the land policy and legal framework governing land tenure, and supporting state and local governments in selected areas develop institutions and procedures for effective land administration and conflict mediation. The SRLG will coordinate closely with other donors to implement programs that clarify and improve LTPR systems, reduce land-related conflicts and increase agricultural productivity and investment. Continuing support for the GoSS, state and local governments, traditional authorities and civil society will be essential to build effective institutions for land tenure and peaceful land-conflict management (USAID 2011a).

The GoSS is also receiving support from other international donors. UN-Habitat has invested resources to support GoSS efforts in the reintegration of IDPs and returnees into South Sudan. UN-Habitat’s current project is helping to: create conditions conducive to access to land; increase self-reliance and peaceful coexistence for displaced and crisis-affected populations; and prevent further displacement. A Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) initiative, funded through its Global Peace and Security Fund, includes a program that builds the capacity of the Southern Sudan Land Commission to regulate and protect land ownership and tenure. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) has been active in South Sudan since 2004, providing protection and humanitarian assistance to IDPs and refugees. NRC efforts include providing information on reintegration and carrying out trainings on community based protection and land issues (NRC 2012; CIDA 2012).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

South Sudan has substantial water resources but these are unevenly distributed across the territory and vary substantially across years, with periodic major flood and drought events. The White Nile flows northward from Uganda through the center of South Sudan and into Sudan. Three major tributaries meet and flow into it: the Bahr el-Ghazal (comprising three sub-basins of Kiir, Loll and Jur); the Bahr el-Jebel (comprising numerous tributaries such as Yei, Aswa and Kiit); and the River Sobat (comprising three sub-basins of Pibor, Akobo-Baro). South Sudan’s varied climate, ranging from the northern desert to tropical rain forests in the south, produces an annual rainfall measuring from 400 millimeters in the semi-arid areas to over 1600 millimeters per year in the tropical rain forest (GoSS 2007).

South Sudan’s surface water sources include perennial rivers, lakes and wetland areas, as well as seasonal pools and ponds, rivers, torrents, streams and extensive floodplains (known locally as toich), and river cataracts, falls and rapids. The White Nile is the dominant geographic feature in South Sudan, flowing across the country. South Sudan is also home to the world’s largest swamp, the Sudd, which covers 30,000 square kilometers. The swamps, floodplains and grassland contain over 350 species of plants, 100 species of fish, 470 bird species, over 10 species of mammals and a range of reptiles and amphibians (GoSS 2011b; GoSS 2007).

The Sudd is an important breeding area for Nile ecosystem fish species. It is the largest source of freshwater fish in South Sudan and breeds eight commercially important species (Nile Perch, Bagrid Catfishes, Nile Tilapia, Carp, Binny Carp, Elephant-Snout Fish, Stubs, Tigerfish, and Haracins). Estimates indicate that the Sudd could provide 100,000 to 300,000 metric tons of fish annually on a sustained basis. The majority of fish caught are smoke dried or sun dried, and then transported to markets throughout the region and sold by retailers. Accurate statistics regarding actual production and consumption have been unavailable since 1991 (USAID 2007).

In addition, the White Nile and its many tributaries provide access to almost unlimited sources of water which service the land, enabling it to support diverse vegetation and crops. Since most people rely on agriculture and livestock to sustain their livelihoods, access to water is an important factor. Constraints to access relate less to total quantity than to distribution patterns over the year, including dry spells in the wet season. As a result, the availability of water is a source of conflict between different pastoralist ethnic groups. In recent years (especially after the CPA), intra- and inter-ethnic fighting has become widespread and frequent, particularly among pastoralist groups and between pastoralists and fishermen, due to increases in the size of livestock populations competing for the same sources of water (Heun and Letitre 2011; GoSS 2011b; USAID 2010b).

Although South Sudan has sufficient fresh water resources to supply drinking water and sanitation, access is hampered by the lack of extraction and infrastructure that would supply the sparsely populated country. Only roughly 47% of people outside of main towns have access to a clean water supply, mainly from boreholes provided by NGOs during the war and only 6–7% percent have adequate sanitation facilities. It is not uncommon for rural women and children to spend most of their day collecting water (GWI 2011).

Juba and other urban centers are no exception. The infrastructure limitations to the distribution network mean that most water is supplied either by tankers or by young men pushing bicycles through the streets transporting plastic water containers. Lack of clean water and sanitation, as well as poor hygiene practices, increase the risk of waterborne diseases that lead to illness and death, particularly among young children (USAID 2012b; GWI 2011).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Since the signing of the CPA, an institutional and legal framework for South Sudan’s water sector has gradually developed. In December 2007, the GoSS adopted the South Sudan Water Policy, stating that access to sufficient water of an acceptable quality to meet basic human needs is a human right. The policy provides that: the right to water shall be given the highest priority in the development of water resources; rural communities shall participate in the development and management of water schemes; and the involvement of NGOs and the private sector in water projects shall be encouraged. Apart from customary laws governing access to grazing and fishing grounds for communal use at a local level, there is currently no formal system for allocating water resources for different social and economic purposes. A more detailed strategic framework for South Sudan’s water policy is being developed (GoSS 2011h; GWI 2011; GoSS 2007).

Shortly after independence, South Sudan became the newest member state of the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), an inter-governmental organization dedicated to equitable and sustainable management and development of the shared water resources of the Nile Basin. Managing the Nile’s water resources is a continuing challenge. Environmental degradation, expected population growth in the region, and construction of a dam in Southern Ethiopia have the potential to jeopardize the livelihoods of South Sudanese relying on the Nile. But the swift announcement of South Sudan’s participation in NBI indicates the priority granted to water, especially from the White Nile, by the government in the new country’s development plans (Mbaku et al. 2012; GoSS 2011h; NBI 2010).

TENURE TYPES AND SECURITY

Under customary law, community members have a right of access to land and water. Pastoralists have the right to use pasture and surface water in any part of their tribal areas. During periods of migration, pastoralists access water on land by agreement with landholders and other pastoralists. Strategies pastoralists use to overcome water shortages include: (1) constructing new water sources in water-deficit areas; (2) balancing appropriate species, age and sex composition of herds; (3) adjusting the positions in space and time of different species and classes of livestock in relation to water supplies and conserving the water and grazing at or around the most permanent and reliable water points (“fallback” or “dry-season” water points); (4) selecting more drought-resistant breeding stock and managing the timing and frequency of drinking; and (5) managing and controlling the water points through regulating access (GoSS 2007; Adams et al. 2006).

Competition over water resources is a common cause of local conflict, especially in areas where resources are limited and where pastoralists and sedentary farmers are forced to share resources. Customary laws and traditional practices governing access to wells and rights to river water are not adequate to address the needs of growing populations of people and livestock, especially in areas experiencing a reduction in water availability or water quality. Competing interests for the diminishing supply of water resources will continue to be a source of tension until clear rules and regulations are developed and enforced by formal and customary institutions (GoSS 2007).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Within the GoSS, the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation has overall leadership in the water sector. The Ministry has responsibility for drafting and overseeing the implementation of policies, guidelines, master plans and regulations for water resources development, conservation and management in South Sudan. It is also charged with: encouraging scientific research regarding development of water resources; overseeing the operation of the Water Corporation of South Sudan; overseeing the design, construction and management of dams and other surface water storage infrastructure for irrigation, human and animal consumption and hydroelectric power; setting tariffs for water use; creating policy on rural and urban water resource development and management; making provisions for local community management and maintenance of constructed water supplies (until state and local governments have the capacity to undertake such functions); initiating irrigation development and management schemes; protecting the Sudd and other wetlands from pollution; and advising and supporting the states and local governments in their responsibilities for water supply and building their capacity to assume all functions vested by the Constitution and GoSS policy (GoSS 2011h).

The Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation also maintains public and private partnerships to implement the GoSS water policy. Key partnerships include: (1) collaborating with the South Sudan Urban Water Corporation (SSUWC) to operate urban water facilities; (2) improving the sustainability of these facilities and expanding service coverage; (3) carrying out surveys for the construction of bridges with the China Construction and Machinery Company; (4) coordinating with the Dams Implementation Unit on national projects in South Sudan; and (5) collaborating with the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) Subsidiary Action Programmes – namely the Eastern Nile Subsidiary Action Programme (ENSAP) and the Nile Equatorial Lakes Subsidiary Action Programme (NELSAP) (GoSS 2011h).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The GoSS developed a Water Policy for South Sudan, which the government passed in December 2007. The policy provides for: the establishment of institutions at the central, state and county level; development of sub-sector strategies for rural water supply, urban water supply and water resources management; establishment of Budget Sector Working Groups; and creation of mechanisms to coordinate the sub-sector strategies. In addition, the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation has plans for projects to: reduce flooding; construct water harvesting facilities; rehabilitate and construct rural water supply and sanitation facilities; rehabilitate and manage irrigation facilities; and prepare plans and strategies to implement the South Sudan Water Policy (GoSS 2011h).

Despite an uncertain legal environment, in September 2011 South Sudan announced plans to construct a hydroelectric dam at Wau in Western Bahr el Ghazal State, but has not indicated when construction will begin (Mbaku et al. 2012).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID supports the water supply and sanitation sectors by working with the government to construct urban water and sanitation infrastructure and to provide clean piped water to urban populations. The Sustainable Water and Sanitation in Africa (SUWASA) Urban Water Sector Reform project was launched in September 2011. The project supports the strengthening of the South Sudan Urban Water Corporation at the national level and the water utilities in Wau and Maridiat the county level. The overall goal is to improve and expand service delivery for urban water customers by building on the substantial water infrastructure investments that USAID has made in South Sudan. The project also aims to further develop the institutional foundation of the urban water sector, paying particular attention to: promoting autonomy (operational, financial and management) of the urban water utilities; improving water utility performance; creating sustainable financial management; and building the capacity of decentralized water utilities. USAID also launched the marketing of water purification tablets in sixteen urban and semi-urban towns and is working through partners to improve water supply and sanitation facilities through well drilling, hand-pump repair, latrine construction and hygiene promotion (USAID 2012c; USAID 2012d).

USAID’s largest investment is the Water for Recovery and Peace Program (WRAPP) that evolved from a 2003 conflict mapping project that identified lack of water as a major cause of conflict in Sudan. WRAPP’s mission is to empower communities in South Sudan to own and benefit from greater access to rural water supply and sanitation infrastructure in a sustainable manner that contributes to improved public health, livelihood opportunities, gender sensitivity and reduction of conflict. Pact Sudan, an International NGO, implements its activities through close partnership with private sector drillers and contractors, INGOs, government, community-based organizations and civil society to provide safe and clean water for the people of South Sudan. Current funding comes from USAID’s Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, the Department of State’s Office of Population Refugees and Migration, the GoSS Multi Donor Trust Fund and USAID through a partnership with Winrock (Pact 2012).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Forests and woodlands make up roughly 29% of South Sudan’s land area (roughly 192,000 square kilometers). Approximately 20% of the country’s land area is forest reserves that receive a special level of protection and management. The country has a wide range of forests, reflecting regional variations in climate and soil. Desert and semi-desert trees and shrubs and riverine forests are found in the northern region of the country, with woodland savanna in the central and southern regions. South Sudan also has some tropical forests as well as teak and pine plantations surviving from colonial times. Most of the country’s forests are open or semi-open habitat (Gafaar 2011; GoSS 2011c; GoSS 2010; TerrAfrica 2010; Clingendael 2009).

South Sudan’s forests are an important source of food, timber, fuelwood and habitat for wildlife, and provide economic opportunities. Fuelwood and charcoal supply 80% of the country’s energy needs. Forests also provide fodder for livestock, as well as marketable non-wood products such as honey, gum arabic, tubers and roots and medicinal plants. Apart from these goods, the forests of South Sudan provide, they also provide ecological and environmental services, including biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration and storage, watershed protection for erosion and sedimentation control, reduced risk of flooding downstream, maintenance of delicately balanced aquatic ecosystems, maintenance of soil fertility, control over soil salinization and regulation of water flows, maintenance of water quality and landscape beauty. The ecological stabilization functions also protect hydropower and irrigation systems (Gafaar 2011; GoSS 2011c; GoSS 2010; TerrAfrica 2010).

In addition, South Sudan’s forests are sources for high-grade timber, including teak, mahogany and ebony. The teak plantations are the largest of their kind in the world. Because of the high demand for premium-quality timber, the country is exporting products to international markets. However, the sector is poorly managed. Reliable numbers quantifying exports and economic potential do not exist, and investment in the forestry and timber trade is limited. Barriers to investment include: lack of access to capital; high taxation rates; high fees and transport charges; poor road and transportation infrastructure; limited institutional capacity of Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry; poor access to international markets; obsolete harvesting and processing machinery and equipment; lack of knowledge and skills among communities in the production and management of forests; shortage of skilled labor; and landmines in forest areas (Gafaar 2011; GoSS 2011c; GoSS 2010; TerrAfrica 2010).

Many non-timber forest products such as shea nut, gum arabic and honey are harvested for local use and to some extent for export. Shea nuts produce a rich oil that can be used to produce body lotion (shea butter), cooking oil or soup. South Sudan has a potential to produce 100,000 metric tons of shea nut per year, but only 10,000 metric tons are produced, with the majority of the harvest consumed locally. It is estimated that only 0.2% is being exported even though there is a growing international demand (Gafaar 2011; GoSS 2011c; NGARA 2012; GoSS 2010; TerrAfrica 2010).

Gum arabic is another resource with substantial economic potential. Prior to South Sudan’s separation with the North, Sudan was responsible for 80% of the world’s gum arabic production, exporting 45,000 tons annually. The gum belt in South Sudan runs across from Eastern Equatoria State, Central Equatoria State, North Bahrel Ghazal State, Warrap State, Unity State, Jonglei State to Upper Nile State. Despite the significance of gum in the livelihoods of people living in the gum belt, there has been only insignificant investment in the gum sector. South Sudanese have not been able to benefit from this natural resource apart from traditional uses of the gum, like chewing. In a few cases, gum collectors sell their harvests at very low prices to middlemen who then sell to traders in neighboring countries. The GoSS does realize the resource’s potential and envisions developing a clear strategy that increases gum production and benefits participating individuals and communities (Gafaar 2011; GoSS 2011c; NGARA 2012; GoSS 2010; GoSS 2009b).

Honey is also abundant in South Sudan and has the potential for external markets and is currently a source of income for rural communities (GoSS 2011c).