Published / Updated: July 2013

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

Ghana is located on the Guinea Coast of West Africa. Its economy is based on agriculture (accounting for one-third of the GDP), gold and cocoa. The vast majority – 68% – of Ghana’s land is used for agriculture and 15% of it is used as permanent natural pastures.

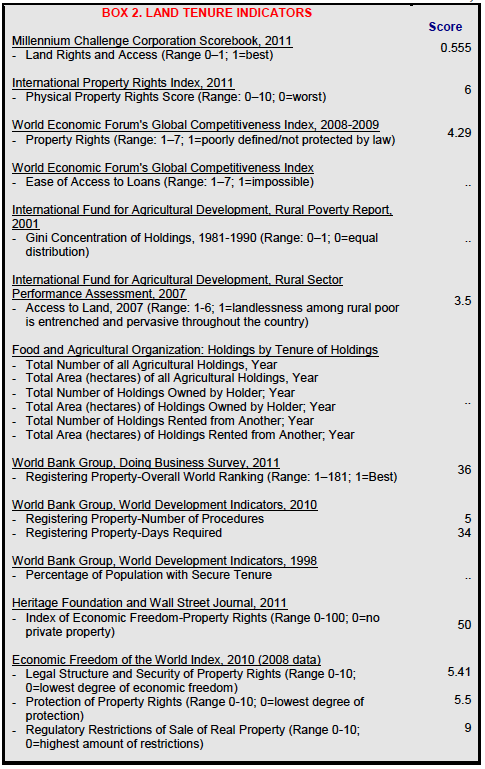

Ghana is characterized by a pluralistic legal system in which customary and statutory systems governing land overlap. The great majority of land in Ghana is held informally, under customary tenure systems. The government and its major donors commenced a large-scale land reform project in 2003 in the hopes of establishing a fair and efficient process for registering land, building capacity in institutions, harmonizing statutory and customary law and improving land-dispute resolution in Ghana.

Mining and biofuel cultivation have recently contributed to land conflicts in the country. Mineral exports constitute 30% of total exports, make up 5% of Ghana’s GDP and constitute nearly 4% of the national government’s revenues. However, mining has created disputes between local communities, corporations and the government because of environmental damage, relocation of inhabitants and breaches of concession agreements. Investment in biofuels has grown in recent years, raising a number of issues pertaining to land rights.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

Although donors have made substantial investments in the land and resource sectors in Ghana in recent years, additional donor support in strengthening land tenure and property rights in the following areas would help Ghana achieve more broadly based economic growth, reduce poverty and increase agricultural productivity. Donors might consider the following interventions:

Ghana is characterized by a pluralistic legal system where customary and statutory systems overlap. Almost 80% of land in Ghana is held under customary tenure. Donors could support Ghana’s customary land tenure systems by partnering with the Land Administration Project to build the capacity of local customary land secretariats to manage land issues at the village level.

Not only is the state acquiring stool land (land controlled by chieftaincies or other customary authorities) through compulsory acquisition, but chiefs are facing increasing incentives to alienate land from their lineages, making their subjects more vulnerable and insecure. Donors could: support programs to sensitize chiefs and their communities about the future impact of land transfers; work with communities and government to clarify land rights; ensure the transparency of land transactions; and improve access to dispute resolution mechanisms. Such efforts could prevent loss of land by small farmers and other community members who depend on secure land access.

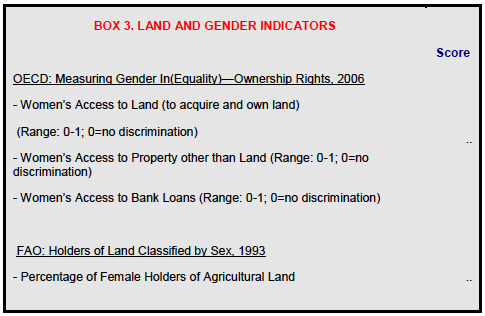

While women’s rights to own and inherit land are protected under law in Ghana, in reality their customary rights to land are insecure and they cannot in practice own land. Donors could assist the government by piloting projects to implement women’s rights through legal education, and land-based programs targeting women.

Ghana does not have a Pastoral Charter as do neighboring countries Mali and Burkina Faso. Land scarcity and farmer-herder conflicts have made the Government of Ghana increasingly hostile to pastoralists. Donors could convene a dialogue on pastoral land rights and the role of pastoralism in Ghana’s economy and encourage legal clarification of the relative rights of pastoralists and farmers. Donors could also support efforts to improve access to fair dispute resolution for conflicts between land owners and pastoralists.

Rural peoples’ land and property rights are increasingly violated by entities that exploit natural resources without consulting or compensating holders of legal rights. For example, mining and timber companies can be granted rights to privately-held or stool land, restricting the owners’ land use and, in the case of mining, causing the owner to be displaced. This insecurity of local land rights is creating conflicts and destroying livelihoods. Donors could work with the government to: clarify and resolve conflicting and overlapping resource tenure rights; clarify institutional jurisdiction and authority over these rights; and develop stronger and more broad-based access to effective dispute-resolution regarding conflicts between rights to land and natural resources.

Summary

Ghana is located on the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa. Its economy is based on agriculture (accounting for one-third of the GDP), gold and cocoa. The vast majority – 68% – of Ghana’s land is used for agriculture and 15% as permanent natural pastures. Nearly all agricultural land in Ghana is rain-fed.

Ghana is located on the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa. Its economy is based on agriculture (accounting for one-third of the GDP), gold and cocoa. The vast majority – 68% – of Ghana’s land is used for agriculture and 15% as permanent natural pastures. Nearly all agricultural land in Ghana is rain-fed.

Ghana’s land is governed by a pluralistic legal system in which customary and statutory systems overlap. Most of Ghana’s land is held under customary tenure and is vested in chiefs, earth priests (who hold spiritual authority over land matters because of their role as the descendants of the first village settlers) or other customary authorities. Approximately 20% of land in Ghana is officially owned by the state, although this number only includes land that the state acquired legally.

Community members access customary lands through their male lineage, and “strangers” (migrants or foreigners) access these lands through the acknowledged community holder of the lands (usually the chief or earth priest). Privately held land is acquired through purchase from the owner. In urban areas, privately held land is acquired through purchase. Customary land can be categorized as allodial title (the highest possible interest in land), customary freehold title, leasehold, or sharecropping (or abunu/abusa) arrangements. While women have legal rights to own and inherit property, in practice under customary law they gain use-rights through their husbands or fathers and do not themselves own land.

The Constitution vests all public land in the State, and all customary land in stool and skins (customary authorities or chieftaincies) families and lineages. Stool and skin land is held in trust for the stool’s community, including their ancestors, living members, and future generations. The State Lands Act grants the President the executive power to acquire land in the public interest, and delineates the procedures for compulsory acquisition of land. The Land Title Registration Act lays out the responsibilities and powers of land registries in Ghana as well as the appropriate manner for registration, and upholds the government’s ability to compel registration of property. The Constitution prohibits foreigners from owning land in Ghana and limits them to leaseholds of no more than fifty years.

The land administration system is currently under reorganization as a part of the Land Administration Project, which is financed by several international donors. The Lands Commission was established in 2008, and brought several previous land-related agencies under one roof to streamline services and improve efficiency. Those agencies became the Land Registration division; the Public and Vested Lands Management division; the Survey and Mapping division; and the Land Valuation division.

The land market is plagued by a lack of accessible information and data, and property registration in Ghana is very complex. Sixty-five percent of Accra’s population cannot afford to purchase urban land.

The frequency of land disputes is high, and land disputes are the most common cause of violent conflict. In rural areas chiefs manage disputes arising from customary law. Community tribunals established by the 1993 Courts Act also settle civil disputes, including land claims. Increasing land scarcity, urbanization, and population growth are creating pressure for local authorities to alienate land to developers and urbanites in peri-urban Ghana. Pastoralists are experiencing similar pressures as the amount of land available for pasture is decreasing due to development.

Statutory laws governing rights to water, forests and minerals have replaced and/or augmented customary rules. The Government of Ghana’s 1996 Water Resources Commission Act vests ownership of all water in the State, which is also responsible for the control and management of water resources. Similarly, the State owns all minerals, and the State has full authority to occupy and use land for mining. The stools own timber trees, yet the Concession Act of 1962 vested all timber trees to the President to administer in trust for the stools.

Land

LAND USE

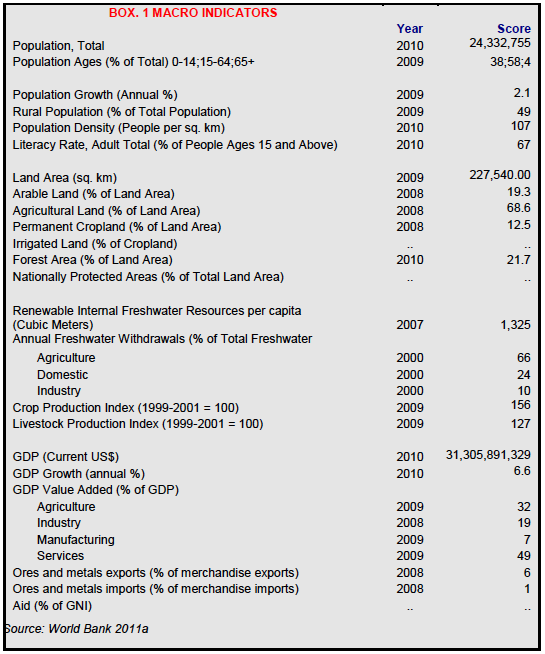

Ghana is situated on the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa. It shares boundaries with Togo, Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire. The country contains 22,754,000 hectares, and the population was estimated to be 24,332,755 in 2010, growing at an annual rate of 2.1%. Forty-nine percent of the population lives in rural areas, and 55% of the active population works in agriculture. The GDP is approximately US $31.3 billion, of which agriculture makes up 32%. The more significant export commodities are gold, cocoa, timber, tuna, bauxite, aluminum, manganese ore, diamonds and horticulture. Ghana has over 100 different linguistic and cultural groups, including the Akan, Ewe, Mole-Dagbane, Guan and Ga-Adangbe (World Bank 2011a; CIA 2011; GhanaWeb 2010; Library of Congress 1994).

Nearly 69% of land in Ghana is used for agricultural purposes, with 18% of the country’s land considered arable and 15% of land used as permanent natural pasture. As of 2005 there were 13,300,000 cattle, and 61,520,000 sheep and goats in Ghana. Food crops include corn, yams and cassava, while commercial crops include cocoa, palm oil, rubber, sugar cane, cotton and tobacco. Ghana does not grow enough cereals to support its population; the country is only 63% self-sufficient in cereals production (FAO 2006; Asante 2004; World Bank; Library of Congress 1994; CIA 2011).

While the use of irrigation is not currently widespread, it is essential for cultivation during the dry season. However an estimated eighty percent of farms are rain-fed, with no functioning irrigation system. Most of these are small farms with an average size of less than 1.2 hectares (80%) (FAO 2005a; Namara 2011).

Seventy percent of Ghana’s urban population lives in informal settlements, and that population is growing at a rate of 2% per year. Only 44% of those living in informal settlements have access to improved sanitation, although 87% have access to safe sources of drinking water. Informal settlements in Ghana are characterized by insecure land tenure and poor quality marginal land (UN-Habitat 2009).

Ten percent of Ghana is covered in inland and coastal wetlands. Ghana signed the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands in 1988, and protects five of its most valuable wetland areas (FAO 2005a; Ramsar 2011).

Ghana has three types of forests: tropical rainforests, tropical moist deciduous forest, and tropical dry forest. These forests are found within the Guinea savanna woodland, riverine woodland, and Sudan savanna woodland ecological zones. Forests cover 40% of Ghana’s land mass, and deforestation occurs at a rate of 1.7% per year. Between1995 and 2000, Ghana lost 35% of forest land cover (Wood Explorer 2008; Siaw 1998; USFS 2011; FAO 2004; Friends of the Earth n.d.).

Ghana has three types of forests: tropical rainforests, tropical moist deciduous forest, and tropical dry forest. These forests are found within the Guinea savanna woodland, riverine woodland, and Sudan savanna woodland ecological zones. Forests cover 40% of Ghana’s land mass, and deforestation occurs at a rate of 1.7% per year. Between1995 and 2000, Ghana lost 35% of forest land cover (Wood Explorer 2008; Siaw 1998; USFS 2011; FAO 2004; Friends of the Earth n.d.).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Ghana’s average farm size is less than 1.6 hectares. Sixty percent of all farms are smaller than 1.2 hectares, and only 15% of farms are above two hectares (FAO 2006).

Large-scale commercial farming is on the rise in Ghana, due primarily to investments by foreign and national biofuels companies in crops like jatropha and sunflowers. Some observers have voiced concern that these investments are compromising the land rights of small farmers, women and other local stakeholders (Hughes et al. 2011; Ghana Web 2010).

The livestock sector makes up approximately 7% of the country’s agricultural GDP. Transhumant pastoralists from neighboring countries acquire land seasonally to pasture their animals, usually from chiefs and other landowners. There is some evidence that these landowners prefer to rent to transhumants because they compensate the landowners beyond what an indigene (an individual belonging to the community) would give as a token gift. However, farmers and herders come into conflict when herders’ animals damage farmland and crops (FAO 2005b; WRI 2011; Sarpong 2006).

Distribution of land rights within customary land holdings is determined by traditional rules. Among patrilineal communities land is passed from father to son. “Strangers” access land through the chief or earth priest, and exercise their use-rights through clearing and cultivating the land that they are given. As the patriarchs of autochthonous lineages (those whose male lineages were the first settlers of a particular area), chiefs and earth priests have both administrative and spiritual authority over land matters. While strangers are also expected to pay “drink money” to the chief or other authority who allocates land, the amount is usually nominal – a symbolic gesture (Tonah 2002).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The formal law governing land rights includes: the 1992 Constitution of Ghana; the State Property and Contracts Act of 1960; the State Lands Act of 1962; the Land Title Registration Act of 1986; the Office of the Administrator of Stool Lands Act of 1994; the Lands Commission Act of 2008; and the Marriage Ordinance of 1884. Ghana does not have a pastoral charter (GOG Constitution 1992; GOG Land Title Registration Act 1986; GOG 1985; FAO 2010; Larbi 2004; Sittie 2006).

The Constitution vests all public land in the President, and all customary holdings in stools, skins, or appropriate families or clans. The Constitution allows foreigners to lease land for terms of up to 50 years (Hughes et al. 2011; GOG 2010; Sarpong 2006; GOG Constitution 1992).

The 1960 State Property and Contracts Act first placed all state property in the hands of the President and granted the President the sole power to compulsorily acquire Ghanaian lands. The 1962 State Lands Act, retaining the provisions of the earlier act, currently governs all compulsory acquisition and compensation (Larbi et al. 2004; GOG Constitution 1992).

The Land Title Registration Act of 1986 lays out the responsibilities and powers of land registries in Ghana and the appropriate manner of registration, and upholds the government’s ability to compel registration of property (GOG Land Title Registration Act 1986; Sittie 2006).

The Land Title Registration Law also established the Land Title Registry to provide a means for the registration of title to land and interest in land. Land title registration was introduced to reduce conflicts over parcel borders, to address weaknesses under the former deed registration system (including multiple registered holders to the same parcel), and to put in place a systematic and compulsory registration of all interests in land throughout Ghana. The purpose of title registration is to give certainty to ownership and to facilitate proof of title to make dealings in land safe, simple and cheap, and to prevent fraud. The 1986 Act provides for registration of allodial title, usufruct/ customary law freehold, freehold, leasehold, customary tenancies, and mineral licenses (WaterAid Ghana 2009; GOG Land Title Registration Act 1986; Sittie 2006).

The Office of the Administrator of Stool Lands Act of 1994 provides the framework for the management of stool and skin lands. Though primarily focused on financial management of customary lands, providing for the collection and disbursement of revenues from stool and skin land, the Act also requires the Office to coordinate with other land sector agencies and traditional authorities on matters related to the administration and development of stool and skin land (GOG Office of the Administrator of Stool Lands Act 1994).

The Lands Commission Act of 2008 formalizes the merger of several major land sector agencies, namely the Survey Department, the Land Title Registry, the Land Valuation Board and the Lands Commission Secretariat, into one umbrella body known as the Lands Commission. This “new” Lands Commission, which functions with four divisions under it, is a departure from the previous Lands Commission (WaterAid Ghana 2009).

The legal framework governing family matters and inheritance is particularly relevant for women’s and children’s rights and access to land. The framework is rooted in the Marriage Ordinance of 1884, which recognized only monogamous marriages and specified that wives and children recognized by the ordinance were entitled to two-thirds of the deceased man’s estate. Meanwhile, the Marriage of Ordinance of 1907 codified a pluralistic legal framework in the area of family law by allowing for polygamous marriages. In the 1960s through the 1980s, legislative reform was undertaken to bridge statutory and customary frameworks in the area of family and inheritance law by clarifying the status and rights of women and children and their access to ancestral land. Further discussion of women’s rights is offered below (see Intra-Household Rights to Land and Gender Differences) (Awusabo-Asare 1990; FAO 2010).

TENURE TYPES

The 1992 Constitution places all public lands in possession of the President, held in trust for the Ghanaian people. It further distinguishes between public lands that are governed by customary tenure and those that fall exclusively under state authority (GOG Constitution 1992).

Ghana’s Constitution vests all public land and all minerals in the State. Public lands include land that is held in trust for Ghanaian citizens for their public interest. The Constitution also describes the nature of customary land ownership as a social trust, whereby stools, skins or lineages hold land in care for their subjects whether living, dead and yet to be born. The Office of the Administrator of Stool Lands collects revenue from stool land, and disburses it appropriately. Customary authorities have voiced frustration in regard to the fact that only 22.5% of this revenue returns to the owner of the land (Sarpong 2006; GOG Constitution 1992; Larbi 2009).

The customary land tenure framework includes several categories of land interest. These include: allodial title, customary freehold title, freehold title, leasehold title and other lesser interests in the land. Approximately 80% of land is vested stools, skins, families or clans (Sarpong 2006; Ubink and Quan 2008).

Allodial title. Allodial title is vested in stools, skins, clans or families, and is the highest form of customary tenure in Ghana. Eighty to ninety percent of all land in Ghana is held under customary title. While allodial title is held in trust with the head of the family or lineage, customary law traditionally requires the consent of elders of the lineage in order for alienations of land by the allodial titleholder to be considered valid. (Kasanga and Kotey 2001; Sarpong 2006; Ubink and Quan 2008).

Freehold title. Freehold title or “common law freehold title” is derived from a freehold grant (by gift or sale) by an allodial rights holder. The rights to the land move from a customary framework to a common law framework only when the parties explicitly agree that common law will regulate the grant and govern any disputes. Freehold title mostly exists in Greater Accra and Kumasi, and in pockets where chiefs gifted or sold stool land to private beneficiaries prior to 1992, when the new constitution forbid this practice (Kasanga and Kotey 2001; USAID 2011).

Customary freehold title. Customary freehold title refers to the rights held by individuals or groups on behalf of the “owner” community (such as the stool or skin). It is based on the idea that male descendants of the first settlers of a region have rights to use a portion of that stool land, should they choose to exercise it by cultivating the land. Customary freehold title is conditionally perpetual, and holders may sell, lease or mortgage their rights. However, the recipient of any transaction must recognize the superior ownership of the stool or skin, and must perform any customary services to the stool or skin when asked. Holders of customary freehold title have no right to minerals found on or under the land (Sarpong 2006; Ubink and Quan 2008; USAID 2011).

Leasehold. Allodial title and freehold title holders can grant leasehold to individuals. Leasehold is a time-bound right. Holders of allodial title may enter into a formal leasehold agreement for up to 99 years with other Ghanaians, and up to 50 years with foreigners (Sarpong 2006; Ubink and Quan 2008; USAID 2011).

Sharecropping. Abunu and abusa are sharecropping arrangements. Under an abunu arrangement, the sharecropper provides one-half of the harvest to the landlord; under abusa, one-third (Sarpong 2006; Ubink and Quan 2008).

In Ghana approximately 80% of land is held under customary tenure regimes, and the State officially owns 20% of all land. Customary rules apply in both urban and rural settings. The 20% state-owned figure may be a low estimate because it does not take into account the numerous state holdings that were not acquired through legal compulsory acquisition (Kandine et al. 2008; Larbi 2009).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

As in much of western Africa, land in many areas of rural Ghana is vested in specific lineages, usually those of the first settlers of an area. The patriarchs of these lineages are often the chief and earth priest, who have both an administrative and spiritual authority over land matters. Within patrilineal communities, land is passed from father to son. In matrilineal groups, land is passed from maternal uncles to their nephews, but always remains in male hands. Strangers (migrants or foreigners) access land through the chief or earth priest, and exercise their use-rights through clearing and cultivating the land they are given. While all autochthonous families have a right to use land because they belong to the stool, skin or clan, strangers are not guaranteed land. Strangers are also expected to pay a token amount to the chief or other authority who allocates land (Tonah 2002).

In southern Ghana customary tenure systems are undergoing changes, including increased share-cropping and tenancy. Land, housing and agriculture markets are expanding, and there is a trend towards individualization of land rights. In the south, especially in urbanizing areas, customary land tenure is eroding whereas in the north, customary tenure systems are still dominant. The majority of Ghanaians practice patrilineal inheritance; however, the Akan people in southern Ghana practice matrilineal inheritance (Kasanga and Kotey 2001).

Most transhumant pastoralists, as strangers, do not have guaranteed access to land. However, in Northern Ghana, Fulani herders care for settled farmers’ herds. Herders negotiate grazing rights with an area’s chief or with the farmer. But with increasing land scarcity, conflicts between herders and farmers are increasing. Animals are destroying crops, and fields are expanding to block traditional pathways to water (Tonah 2002).

Customary tenure systems still dominate in urban and peri-urban Ghana. With increasing urbanization and its attendant pressures on land, families are alienating land for development and transferring land to outsiders. In urban areas many land transactions still follow customary practices, and the receiver of land is expected to offer a token payment to the original owner. Because of land pressures in urban Ghana, these token payments have increased, and now they are nearly equal to the market rate for land. Land in urban and peri-urban areas is owned by customary authorities but the State controls the allocation of funding gleaned from those lands through the Office of Stool Lands (Mends and Meijere 2006; Kandine et al. 2008; Larbi 2009).

While formalization of land ownership is more common in urban areas, rates of land registration are very low throughout the country. In peri-urban Accra, approximately 80% of land transactions take place informally. In a study published in 2011 (based on a nationally representative sample), researchers found that of 88% of respondents who owned land, only 39% had formally registered their holdings. Seventy percent of Ghana’s urban population lives in slums, and that population is growing at a rate of 2% per year. Informal settlements in Ghana are characterized by insecure land tenure and poor-quality marginal land. Only 44% of those living in slums have access to improved sanitation, although 87% have access to safe sources of drinking water (Twerefou et al. 2011; Kandine et al. 2008; UN-Habitat 2009).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

The Constitution prohibits discrimination based on gender, guarantees women’s right to own and inherit property, protects equality before the law, and tasks the Government with ensuring women’s full integration into the mainstream of economic development. However, Article 17[A] of the Constitution allows for exceptions in personal law, including but not limited to the areas of marriage, divorce, and devolution of property (FAO 2010; GOG Constitution 1992).

Moreover, despite Constitutional guarantees, discrepancies exist between statutory law and customary law. According to formal legislation, men and women enjoy equal rights with regard to property. But according to common practice men, not women, hold and wield authority over property in most parts of the country. In Ghana 10% of women hold land in their own names, while they own 30% of cocoa land. However the percentage of women owning and controlling land varies per region, and one 2011 study showed that tenure security is better for women in Brong Ahafo and Eastern regions than it is in the rest of the country (FAO 2010; IFAD 2008; IDLO; Grown et al. 2005; AllAfrica 2011).

Family laws and inheritance laws were founded in the Marriage Ordinance of 1884 and the Marriage of Mohammedans Ordinance of 1907. The passage of these acts helped codify separate pluralistic legal frameworks in the governance of family matters. The former, borrowed from English laws of the time, granted wives acknowledged by the ordinance – and their children – two-thirds of the deceased husband’s estate. Additionally, The Marriage Ordinance recognized only monogamous marriages, solely allowed for remarriage after establishing a divorce, and made no provisions for multiple marriages under Sharia law. The law initially affected few individuals but over time it was applied also to customary marriages. The Marriage of Mohammedans Ordinance of 1907, on the other hand, covered individuals married under Islam. The Ordinance permitted polygamous marriages and provided procedures for marriage registration and divorce (FAO 2010; Manuh 1997; Sarpong 2006).

Family laws and inheritance laws were founded in the Marriage Ordinance of 1884 and the Marriage of Mohammedans Ordinance of 1907. The passage of these acts helped codify separate pluralistic legal frameworks in the governance of family matters. The former, borrowed from English laws of the time, granted wives acknowledged by the ordinance – and their children – two-thirds of the deceased husband’s estate. Additionally, The Marriage Ordinance recognized only monogamous marriages, solely allowed for remarriage after establishing a divorce, and made no provisions for multiple marriages under Sharia law. The law initially affected few individuals but over time it was applied also to customary marriages. The Marriage of Mohammedans Ordinance of 1907, on the other hand, covered individuals married under Islam. The Ordinance permitted polygamous marriages and provided procedures for marriage registration and divorce (FAO 2010; Manuh 1997; Sarpong 2006).

In 1969, with the establishment of the Law Reform Commission, the government focused its efforts on regularizing laws, and in 1971 the Matrimonial Causes Act passed, establishing the legal structure for both monogamous and polygamous marriages, providing grounds for divorce, and placing courts adjudicating Muslim divorces under the auspices of the Act (FAO 2010; Sarpong 2006).

Legislative reforms passed in 1985 regarding laws governing marriage, divorce, family responsibility, and inheritance aimed to lessen inequality endured by women and children under customary systems. These reforms included four laws on marriage passed by The Provisional National Defense Council (PNDC): the Customary Marriage and Divorce (Registration) Law (PNDC L112); the Administration of Estate (Amendment) Law (PNDC L113); the Head of Family (Accountability) Law (PNDC L114); and the Intestate Succession Law (PNDC L111). The Head of Family (Accountability) Law secures family property by empowering heads of family to manage property in ways that benefit the nuclear unit. Also, a statutory provision allows family members to file a claim in High Court to seek redress against the head of family for mismanaging their property (Manuh 1997; Awusabo-Asare 1990; FAO 2010; FAO 2010).

Meanwhile, inheritance laws codified in the Intestate Succession Law have helped ameliorate the position of women and children in inheritance proceedings. The law encompasses property that is “self-acquired” by the deceased, and not property that he or she holds on behalf of the lineage or community. Thus the extended family retains possession over family property but the law gives “wives and children in matrilineal and patrilineal communities definite rights in the estate of their deceased husband or father.” The law, however, leaves open the question of how these rights will be protected in practice. The Intestate Succession Law also protects families through stipulating that estates valued at 10 million Ghanaian cedis (worth approximately US $400,000 at the time the law was adopted) and below devolve automatically to the spouse or child so as to safeguard their livelihoods. There is disagreement among Ghanaians about this law, especially regarding the relinquishment of property by deceased men’s family members (Manuh, 1997; Awusabo-Asare 1990; FAO 2010; FAO 2010; Trading Economics 2011; AllAfrica.com 2011).

In most customary land tenure systems, community-level decision making about land is the exclusive purview of chiefs, or family heads who exercise that role on behalf of the community, clan or family. Thus whether women are located within matrilineal or patrilineal cultures, it is the men in their families who more or less preside over the allocation of resources owned by the family (Minkah-Premo et al. 2004; FAO 2010; Sarpong 2006).

Studies have shown that women’s access to usufruct is affected by a number of factors, including patterns of marital residence, land scarcity, production relations and gender bias in the size of land given to women among some groups. The most crucial determinant is the sexual division of labor and the organization of production in both patrilineal and matrilineal areas (Minkah-Premo et al. 2004).

Stability of marriage and good relations with male relatives are critical factors in the maintenance of women’s land rights. Thus a married woman may gain access to land with the permission of her husband, but it is not uncommon to find that the woman loses her land and crops after a divorce or upon the death of her husband. This may also apply to young widows who fail to cooperate with their in-laws after the death of their husbands. A woman’s rights to land obtained through marriage may also change if her husband remarries under a polygamous arrangement (Minkah-Premo et al. 2004; FAO 2010; Sarpong 2006; AllAfrica.com 2010).

In addition to receiving access to land through male family members, women also obtain land rights through renting, purchasing and sharecropping. Sharecropping as a primary source of land access for women is problematic for a number of reasons, however. Landlords may – and often do – change the terms of tenancy at will, an option made easy for them by the verbal nature of many of these arrangements. Studies of sharecropping arrangements have found their terms disadvantageous to tenants. One particularly harmful practice is the required turn-over of half the crop to the landlord as opposed to one-third or one-fourth (Minkah-Premo et al. 2004; AllAfrica.com 2011).

In the absence of legislative provisions, the courts have in recent years attempted to use general principles of equity to decide issues of property in divorce cases. The cases show that, to succeed in a claim for beneficial interest in property acquired during marriage, the claimant spouse has to prove that there was agreement between the spouses to the effect that he/she would have a beneficial interest in the property, or that the claiming spouse made a substantial financial contribution to the acquisition of the property (Minkah-Premo et al. 2004).

However, rural women in agriculture claiming relief under the Matrimonial Causes Act would therefore have to prove the nature of their contribution, which could include the duration of time she has spent working on her husband’s farm as well as the kind of activity she was actually engaged in, including any financial contributions she may have made. Apart from the fact that rural women tend to have more limited access to formal justice systems, including the courts, it is also clear that in practice it would not be easy to quantify the value of such contributions to the acquisition of property during marriage. These challenges are further reinforced by the customary law principle which requires wives to assist husbands in livelihood duties without entitling them to any beneficial interest in property acquired with the proceeds of such assistance. Thus such women may have no guarantee that they would be compensated for several years of assistance to their husbands (Minkah-Premo et al. 2004).

Also, increasing instances of compulsory land acquisition with inadequate compensation have had a disproportionately negative impact on women. Rural women tend to be almost entirely dependent on the land for their livelihoods and have the fewest options when deprived of their land. Women also tend to have the weakest voice with regards to issues of land management, apportionment of compensation money when paid, and land alienation procedures generally (Minkah-Premo et al. 2004).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Until Ghana reorganized its land administration in 2008, barriers in the sector included poor coordination between the ubiquitous government agencies responsible for land issues, a lack of both human resource and systems capacity (for example, there was no electronic cadaster), and a weak land registration system. The 2008 Lands Commission Act consolidated four separate agencies previously responsible for land administration under one organization (the National Lands Commission). These agencies became divisions within the new Commission: the Land Title Registry division; the Public and Vested Lands Management division; the Survey and Mapping division; and the Land Valuation division. The Lands Commission seeks to improve management of land administration (MiDA n.d.; Jones-Casey and Knox 2011; Mustapha 2006).

The Land Valuation Division manages compensation for lands acquired by government, valuations of property rating and interests in land, and values of government-rented land. It also advises the Lands Commission and Forestry Commission on royalty payments on forestry property and advises government on valuation of interests in immovable property (FAO 2010; FAO 2006; Kasanga 2001).

The 1992 Constitution also established ten regional Lands Commissions. The current functions of these commissions include the management of public lands and other lands vested in the President or in the Commission. The Commissions are also responsible for advising the Government and other authorities on the policy framework of land administration and development; creating recommendations on national policy regarding land; supporting the implementation of a comprehensive program of land title registration; and managing all other assigned lands and forestry needs (Kasanga 2001).

Customary governments, known as stools and skins, are vested with control over customary or stool lands, which are held in trust for subjects of the stool. The land priest is generally responsible for control over land ownership, land distribution, and land disputes. The Administrator of Stool Lands, a decentralized office with thirty district-level offices throughout the nation, assists in the demarcation of holdings to generate revenue from land vested in customary authorities; it also researches land issues. The 1992 Constitution mandated (and the 1994 Parliament established) the Office of the Administrator of Stool Lands to manage activities related to the stool lands (MiDA n.d; FAO 2010; FAO 2006; FAO 2010).

The Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources manages Ghana’s land, forest, wildlife and mineral resources to allow for socioeconomic growth and development. Its stated objectives are to “(1) develop and manage sustainable lands, forest, wildlife and mineral resources; (2) facilitate equitable access, benefit sharing from and security to land, forest and mineral resources; (3) promote public awareness and local communities’ participation in sustainable forest, wildlife and land use management and utilization; (4) review, update, harmonize and consolidate existing legislation and policies affecting land, forest and mineral resources; (5) promote and facilitate effective private sector participation in land service delivery, forest, wildlife and mineral resource management and utilization; (6) develop and maintain effective institutional capacity and capability at the national, regional, district and community levels for land, forest, wildlife and mineral service delivery; and (7) develop and research problems of forest, wildlife, mineral resources and land use” (GOG 2008a).

The Ministry also oversees the Land Administration Project (LAP), an initiative to improve land administration and land security. To improve the administration of customary lands, the project established 33 new Customary Land Secretariats and strengthened an additional three Secretariats between 2004 and 2008. The Customary Land Secretariats hold authority to record and manage allocations and transactions of land by customary authorities. Additional institutions with varying degrees of responsibility to support land administration, rights, and development include: the Regional Houses of Chiefs which manages disputes arising from customary law; the Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs (and specifically the Women’s Development Fund which supports women in small-scale business via micro-credit); the District Assemblies’ Common Fund (a Constitutionally guaranteed pool of resources that allocates some funds to women farmers); and the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (World Bank 2011e; FAO 2010; GOG 2011f).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

The land market in Ghana has high levels of uncertainty, related in large part to the predominance of informal, overlapping land rights claims. Land rights insecurity impedes investment in both rural and urban areas, and has therefore slowed economic growth. In urban areas, the lack of clear titles and the predominance of land disputes have discouraged development and contributed to supply shortages in the housing sector. Despite these hurdles, a vibrant market for land sales and lease is emerging in urban and peri-urban locations. The demand for urban land continues to grow as urban populations rise due to immigration and movement from rural areas; approximately 44 percent of the country is now urban. (Mahama and Antwi 2006; IMF 2011; USAID 2011; Twerefou et al. 2011; Reed et al. n.d.; Aryeetey and Udry 2010).

Impediments to the land market include a lack of accessible information and data. Information about sales values and property sales is not public or recorded in a database, rendering it difficult for households and developers alike to assess land values. According to the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, “transactions on the market are shrouded in secrecy.” There is also a lag in development in areas that do not have adequate infrastructure (roads, sewer, etc.) to support housing, resulting in half-completed housing on the urban periphery (Mahama and Antwi 2006).

Property registration in Ghana is very complex. As of 2010, land registration officially required 34 days and five procedures. However, long delays have plagued the registration system for years. The process includes: submitting an application; publishing the transaction; assessing the property value; and paying relevant fees. For individuals, the process is inhibitive, especially considering that 65% of the population of Accra cannot afford to purchase new land, and most Ghanaians spend more than 40% of their income on housing (IFC 2011; Mahama and Antwi 2006).

Public land can be acquired through applying to the Lands Commission or Regional Lands Officer, but private land (converted from stool land before 1992) must be granted by the owner (MiDA 2010; Global Property Guide 2011).

The Constitution allows foreigners to lease land for 50-year renewable terms but foreigners cannot own land in Ghana under Article 266. The availability of long-term renewable leases has encouraged international investment in Ghana, especially in biofuel cultivation. This trend is further motivated by Ghana’s National Energy Plan of 2006, which seeks to increase renewable use and production to mitigate climate change (Hughes et al. 2011; GOG 2010; GOG Constitution 1992).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The 1992 Constitution lays out the basic policy for land acquisition, stipulating that no property or interest over property will be compulsorily acquired unless certain conditions are satisfied. Conditions may be met when the state: (1) requires property for defense, public safety, public health, and community, town, and country planning; (2) has justifiable reason; (3) makes provisions for prompt and fair compensation; (4) makes available access to the High Court for those who have an interest in or right over property; (5) takes on the onus to resettle displaced individuals; (6) uses the acquired property for the public interest; and (7) provides the owner prior to the takings the ability of re-acquisition if the land is not used for the intended purpose or in the public interest. The 1960 State Property and Contracts Act placed all state property in the hands of the President and granted the President the sole power to compulsorily acquire Ghanaian lands. The1962 State Lands Act, retaining the provisions of the earlier act, currently governs all compulsory acquisition and compensation (Larbi et al. 2004; GOG Constitution 1992).

The Lands Commission works within these statutory provisions to manage processes of compulsory acquisition by the state. The Commission relies on a permanent site advisory committee to advise it of the suitability of property to be compulsorily acquired. Any land acquired through the 1962 State Lands Acts is allocated by the Minister to various state organs. All allocated lands require a Certificate of Allocation. Individuals’ receipt of a lease or license for allocated lands requires a banker’s reference of approximately US $1600, thereby facilitating residential needs of middle- to upper-income classes and effectively barring low-income groups. However, while the country has very strong legislation protecting land owners in the compulsory acquisition process, some maintain that the state is occupying a significant amount of land outside of formal legal channels (Larbi et al. 2004; Larbi 2009).

The State has been compulsorily acquiring non-state land for reasons that some argue are not in the public interest, and stakeholders other than formal rightsholders (those, for example, with traditional or customary claims or access to the land) seldom benefit from compensation paid. The State’s broad exercise of compulsory acquisition derives in part from the legal definition of public interest, which can be expanded to include private companies investing in ways that might provide indirect benefits to the public (for example, gas stations and hotel development that encourages tourism). Compensation is paid to the holder of allodial title (usually the stool or skin) for the supposed benefit of the community, but community members with informal rights or access to the land often do not receive payment (Larbi 2009).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

In Ghana, land disputes and conflicts are prevalent and largely revolve around access to land and issues of land tenure security. Conflicts over land are increasing, and sometimes become violent. According to public opinion, 16% of respondents cited boundary or land disputes as the most common cause of violent conflicts (Ayee et al. 2008; Tsikato and Seini 2004; Aryeetey and Udry 2010).

Conflicts occur between individuals, chiefs, governments, and various economic, social, and ethnic groups. At the intra-ethnic group level there are conflicts between chiefs and their members, and at the individual and inter-ethnic group level there are often conflicts between migrant landholders and host groups. There are also conflicts between governments and social groups, and between transnational corporations and social groups (Ayee et al. 2008; USAID 2011).

Traditionally, and today in rural areas, chiefs manage disputes arising from customary law, with the land priest largely responsible for control over land ownership, land distribution, and land-dispute resolution. Customary land tenure systems developed in the context of ample land to support subsistence agriculture, and thus without significant pressure on land-use and access. However, due to the growth and intensification of commercial agriculture and the increased demand for land for subsistence farming, land pressure has increased, and the conflicts faced by chiefs and lineage-heads are new, intensifying, and increasing in volume. Additionally, in this context, traditional rulers can bypass the authority of local land-owners and community heads, making decisions that, while arguably for the broader economic interest, result in unrest. According to news accounts, alienation of land by chiefs is increasing. Urban expansion and conversion of farms into developments are two examples of this. Chiefs are accused of not distributing payment from these sales, leases, or compulsory acquisitions to their subjects, provoking anger among local communities (GOG 2008a; Hughes et al. 2011; FAO 2010; Kasanga and Kotey 2001; Fred-Mensah 1999).

In western Ghana oil discoveries and subsequent investments in land have driven up housing and property prices. In some cases local chiefs are facilitating these transactions without sharing the benefits with the community (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2011).

Following Ghana’s independence, the government developed a layer of statutory law aimed at clarifying land tenure issues and conflicts. For instance, the statutes of limitations that apply to land in Ghana provide that following 12 years of continuous possession, challenges to individual land claims are barred. The 1986 Land Title Registration Law strengthens the statute of limitations and aims to resolve land conflicts via ensuring clear title. However, these statutory provisions often cause additional conflicts due to their lack of harmonization with customary land laws. For example, Ghana’s ethnic groups do not customarily have time limits on action to recover land rights. Whereas the 1986 Land Title Registration Law provides for redress in the national court system, implementation is centered in major cities. Given the lack of synchronization of Ghana’s pluralistic land tenure system of statutory and customary laws, land conflicts and disputes proliferate as claimants assert different legitimate rights in a legal environment (Fred-Mensah 1999).

The 1993 Courts Act established community tribunals throughout Ghana vested with the power to settle civil disputes including land claims and landlord-tenant conflicts. Other institutional organs that can develop and implement solutions to land-related conflicts are the decentralized local legislative bodies (Fred-Mensah 1999).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

The largest land-related intervention in Ghana is the Land Administration Project (LAP) (Phases 1 and 2), which is supported by the World Bank, the Nordic Development Fund, the German Reconstruction Credit Institute (KFW), Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the Department for International Development (DFID), and the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ). The total cost of Phase 1 was approximately US $55 million, of which the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) contributed approximately US $20.5 million. The broad purpose of LAP was to initiate implementation of the National Land Policy, which launched in June 1999. The project sought to improve the land administration and management systems in Ghana by streamlining service-delivery and eliminating backlogs, ameliorating the mapping systems and capacities of land agencies, and drafting the land and land use planning bills. The second phase of the project runs from 2011 to 2016, and has a budget of approximately US $72 million. Its four primary objectives are: (1) to improve the land administration framework; (2) to decentralize and improve delivery processes for business and services; (3) to improve the special data and maps needed for land administration; and (4) to strengthen project management and further develop human resources (Ghana LAP 2011; GOG 2008a; World Bank 2011b; World Bank 2011d; World Bank 2010; USAID 2011).

The five-year US $547 million Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compact in Ghana, signed in August 2006 between the Government of Ghana and the United States, includes an Agricultural Program with a land-tenure component aimed at facilitating land access for growing commercial crops. Within the Compact, the Land Tenure Facilitation Activity (total US $3.9 million) included: pilot registration programs; public awareness campaigns related to land rights and land laws; assistance of circuit courts to process land conflicts; and construction of local Land Registration Divisions. Implementation of the Land Tenure Facilitation Activity brought to light high levels of insecurity for secondary land rights, such as those held by tenant farmers and sharecroppers. To address this issue, MiDA Ghana initiated an approach to systematically convert verbal leases into written agreements, and to register them. The Land Tenure Facilitation Activity is scheduled to end in February 2012 (MiDA n.d.; GOG 2008a; World Bank 2011b; MiDA 2008; MiDA 2010; USAID 2011).

Ghana is one of 13 African countries to receive a grant from the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). The grant, totaling US $13 million, aims to improve food security. The money will go toward training farmers, providing scholarships to university students studying agricultural science, improving seedlings, and developing new crop varieties. The current grant cycle will run for approximately seven to ten years (Ghana News Agency 2009).

USAID funded the Ghana Land Titling Reform Project, with a budget of US $300,500, between 2009 and 2012. The project aimed to improve access by the poor to property titles and to housing finance (USAID 2011).

A smaller land registration program is led by the Ghana-based NGO Medeem, which attempts to secure land rights for poor Ghanaians through paralegal titling and GIS technologies (Medeem 2011).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Ghana has three major river systems, with the largest of these, the Volta river system, accounting for 70% of the country’s river water. All three river systems are shared by Ghana with its neighbors – Côte D’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Togo, Benin and Mali. Ten percent of Ghana’s total area is made up of wetlands (Sarpong 2006; FAO 2005a).

There are two rainy seasons in the coastal, transitional and forest zones of Ghana; in the rest of the country there is only one rainy season. Ghana receives an average of 1187 millimeters of rainfall annually. Irrigation, though not commonly used, is essential for cultivation during the dry season. Eighty percent of all small farms are rain-fed (FAO 2005a).

Drinking water is sourced from both ground and surface water (such as lakes or rivers). According to the World Bank, 90% of Ghana’s urban population has access to an improved water source, compared to 74% of the rural population. While those numbers seem substantial, it is also noteworthy that Ghana experiences high mortality rates from waterborne illnesses resulting in diarrhea (World Bank 2011a; MIT News 2010).

Ghana’s total renewable water resources amount to 53.2 cubic kilometers per year. The majority of water withdrawn is used for irrigation, industry and municipalities. Irrigation used 66% of the 982 million cubic meters withdrawn in 2000, while industry only used 10% (FAO 2005a).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Water Resources Commission Act of 1996 establishes the Water Resources Commission of Ghana (the WRC, which began operations in 1998) and outlines its responsibilities to manage and regulate water use and water policy in Ghana. The Act also vests rights to public water in the President. Prior to the Water Resources Commission Act water-related legislation gave managerial rights to a variety of ministries and agencies. No single entity was responsible for managing, measuring, regulating or controlling the use of Ghana’s water (Sarpong 2006).

In 2002, the WRC developed a draft water policy to manage national water policy and integrate the system of national water resource management. The Draft Water Policy delineated the country’s need for water to support industries and livelihoods such as herding, farming, and fisheries, and described very broad objectives (such as rule of law, democratization, and good governance). The draft was later adopted as the National Water Policy (NWP). However, the extent to which the policy has been implemented is not clear (Encyclopedia of Earth 2008; van Edig et al. 2002; Laube 2006; GOG 2011e).

TENURE ISSUES

In Ghana, statutory laws governing water tenure have replaced and/or augmented customary rules. The Government of Ghana’s 1996 Water Resources Commission Act vests ownership of all water in the State, which is also responsible for its control and management. The Act also gives the State the power to grant water rights. However, it does not describe formal avenues for dispute resolution (Sarpong 2006; GOG Water Resources Commission Act 1996).

Obtaining formal water rights, whether for water diversion, storage or damming, requires submission of an application for a water-use permit and payment of an administrative fee. The processing time is estimated by the Water Resources Commission to be six months, unless delayed by the environmental permitting process (GOG 2011e).

Outside of these formal systems of law, traditional practices involving water rights are complex and ever-changing. Generally speaking, water rights are strongly tied to land rights. Water, like land, is vested in stools and skins (through the chief) as wells as lineages and families. Religious and customary authorities (such as priests) keep the system in check by ensuring that non-compliant community members atone for their mistakes. These customary authorities also resolve water-use disputes (Sarpong 2006).

Household water rights are – in practice – tied to a household’s connection to a “pump community” covered by the National Community Water and Sanitation Program (NCWSP) or to access to a well. Pump communities require a fee for entrance, and a flat rate for use of water. However, water sources that are not improved (such as natural rivers) are still governed by customary norms (Sarpong 2006).

Conflicts over water resources arise among various stakeholders, and especially between local communities and mining companies whose mining practices contaminate water supplies. One report examining the impact of mining in Wassa West District states that conflicts have occurred as a result of insufficient mechanisms for communication between stakeholders, resulting in a lack of trust. The study suggests increasing forums for mediation and discussion and the inclusion of a wide array of stakeholders within dialogues, including representatives of the government, NGOs and civil society as well as members of the affected communities and mining companies (Singh et al. 2007).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Water Resources Commission (WRC) gathers stakeholders in the water sector and controls Ghana’s water resources (GOG 2011e).

Water administration in Ghana is complex because, though the Water Resources Commission Act integrates the water management system on paper, in practice integration of the water management system under the umbrella of the WRC entails wresting power from other government ministries and agencies that historically had autonomous control over water-use for their respective areas, i.e. irrigation and mining. The general weakness of governance, and legal pluralism at the local level, make the harmonization of water administration challenging (Laube 2006; FAO 2010; van Edig et al. 2002).

The Ministry of Water Resources, Works and Housing is home to most agencies that deal with the country’s water resources, from irrigation to sanitation and environmental protection. The Ministry houses the Department of Hydrology, which is responsible for protecting coastal waters, assessing flood waters, and for major drainage projects. It was established in 2004 (GOG 2011c).

The Ministry of Water Resources, Works and Housing’s Water Directorate manages Ghana’s drinking water supply. The Water Directorate leads Ghana’s water sector work for the Ministry. Among its objectives are setting water policies for the country, sourcing funds for projects, and monitoring and evaluating the water sector (GOG 2011c).

The Community and Water Sanitation Agency was launched in 1998 to ensure that rural communities and smaller municipalities have access to sanitation and healthy drinking water (CWSA 2011; GOG 2011c).

The Ghana Irrigation Development Authority (GIDA), established in 1977, is located within the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA). GIDA is charged with managing irrigation dams, developing irrigation schemes for farmers, and maintaining water quality in the geographic areas where the Authority works. GIDA has been criticized for its low capacity and ineffective services (GOG 2011c).

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) attempts to minimize the impact of development on water resources and monitors wastewater (FAO 2005).

The Water Research Institute is a scientific research entity that gathers hydrological data, studies groundwater resources and tests irrigation technology (Encyclopedia of Earth 2008; FAO 2005a).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The Government of Ghana is in the process of constructing a 185-meter-high dam that will create a reservoir 444 square kilometers in area. Water retained in the reservoir will be used for irrigation to support animal husbandry and crop cultivation. The Bui Power Authority began constructing the dam in 2009, and the project is expected to be complete in 2013 (Bui Power Authority 2011).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Many donor organizations and NGOs have invested in Ghana’s water resources. WaterAid has been present in Ghana since 1985 and works in the Eastern, Ashanti, Northern, Upper East and Upper West regions of Ghana providing support to the Government of Ghana to provide sanitation and water services to its citizens (WaterAid Ghana 2011; WaterAid UK 2011).

SWITCH (Sustainable Water Management Improves Tomorrow’s Cities’ Health) is an international research group funded by the European Union (EU) to create new solutions for sustainably managing urban water supplies. SWITCH is coordinated by UNESCO-International Institute for Infrastructural, Hydraulic, and Environmental Engineering’s Institute for Water Education (IHE). The project began in 2006 and ended in early 2011. The project’s complete budget (for all 16 countries) is EUR €23 million (SWITCH n.d.; EC 2006).

In 2010 the African Development Bank (ADB) gave over US $12 million to the Government of Ghana for the Small Scale Irrigation Development Project to develop irrigation and train farmers (ADB 2010).

The World Bank approved a US $77.34 million Sustainable Rural Water and Sanitation Project in Ghana in 2010 to be concluded in 2016 to improve sanitation and provide a clean water supply to rural communities. The project will include the building of water piping systems and hygiene training (World Bank 2011c).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Ghana has three types of forests: tropical rainforests, tropical moist deciduous forest, and tropical dry forest. These forests are found within the Guinea savanna woodland, riverain woodland, and Sudan savanna woodland ecological zones. Forests cover 40% of Ghana’s land mass, and deforestation occurs at a rate of 1.7% per year. From 1990 to 2005, Ghana lost 35% of forest land cover (Wood Explorer 2008; Siaw 1998; USFS 2011; FAO 2004; Friends of the Earth n.d.).

In addition to severe deforestation, Ghana has also experienced significant levels of forest degradation, attributed to wildfires, forest clearing for cocoa and other crops, untenable logging practices, population growth and mining (Friends of the Earth 2007; Agyarko n.d.; Tang 2010; USFS 2011).

Two percent of Ghana’s forest area is legally protected in parks and forest reserves. Ghana has seven national parks and forest reserves. The largest of these, Kakum National Park, includes 360 square kilometers of Ghana’s tropical rainforest (out of a total of 20,000 square kilometers of tropical rainforest in Ghana) (GOG ND; GOG 1994).

Ghana’s forests are very important for livelihoods, for the national economy, and for their cultural value. They are used for fuelwood and charcoal, medicinal plants, building materials and other non-timber forest products. Six percent of the country’s GDP comes from the forest sector (Friends of the Earth n.d.).

One area of concern is chainsaw milling, which is the conversion of logs into lumber with chainsaws on the site of harvest. Although this practice is illegal in Ghana, it is estimated to supply at least 80% of the country’s hardwood market. Conflicts have ensued between chainsaw millers and the Forest Services Division, which confiscates millers’ supplies (Tropenbos International 2009).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Timber Resources Management Act of 1997 prohibits timber harvesting in designated areas except by those who hold rights via a timber utilization contract. Timber rights apply to lands where such rights have already been allocated, to alienation holdings, and to unallocated public or stool land. Rights to timber resources will not be granted on land with farms or forest plantations, land where individual or group owners have grown timber, or land that is subject to alienation holdings. According to the Act, the Minister of Lands, Forestry and Mines – on behalf of the President – approves rights recommended to them by the Forestry Commission. The Timber Resources Management Act became the primary instrument for managing forestry issues after replacing and synthesizing previous forestry legislation (GOG Timber Resources Management Act 1998; FAO 2004).

The primary aim of the Timber Resources Management Act is to achieve sustainable timber management by controlling entry into the timber industry through increasing formal barriers. The main tenets include the following: (1) harvesting on land where harvesting rights may be granted is limited to holders of a TUC, or Timber Utilization Contract (which only private entities incorporated into Ghana may hold); (2) TUCs must contain a binding Social Responsibility Agreement that outlines a reforestation plan and commits the company to addressing the social needs of the community where timber is to be harvested; (3) the Forest Commission has the ability to recommend to the Minister that TUCs be suspended or retracted upon certain breaches, and lastly; (4) TUCs are transferable, contingent on approval by the Forest Commission and the Minister (Kufuor 2000; GOG 1997).

Prior to the Timber Resources Management Act of 1997, the Forest and Wildlife Policy of 1994 was adopted to manage Ghana’s forest and wildlife resources through: developing forest-based industries; promoting public awareness and forestry management; and enhancing capabilities at all levels of forest and wildlife resource management. The strategies outlined in the policy include: expanding the amount of land under forest reserves; rehabilitating degraded mining areas and harvested rainforests; and encouraging local communities to protect forests. It has been criticized for being too focused on the large-scale timber industry, not taking into consideration livelihoods for the poor who depend on the forests, and not providing any strategic guidance for the incorporation of local communities into forest management. The policy is under review by a committee convened by the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources and the Forestry Commission. The Forestry Development Master Plan (1996–2020) is guiding implementation of the current policy (GOG 2011g; GOG Timber Resources Management Act 1997; GOG Forest and Wildlife Policy 1994; Tropenbos 2010; Ghana News Agency 2010).

The National Land Policy, the first in Ghana’s history, was published in 1999. It includes guidelines for the “optimum usage of land,” including for forestry purposes. The Land Administration Program (LAP), which streamlines and restructures Ghana’s land administration system, was designed to implement this policy (Hacibeyoglu 2008; Kasanga 2001).

The Government of Ghana, through the National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) and accompanying implementing strategy – the Ghana Environmental Resource Management Project (GERMP) – has put into place an Environmental Resource Management System and Environmental Information System (Iddrisu et al. 1999).

TENURE ISSUES

The stools own timber trees, yet the Concession Act of 1962 vested all these to the President to administer in trust for the stools. Under this framework, and per the 1992 Constitution, the government grants timber concessions to companies and shares revenue with stools and local governments. Further, the Timber Resources Management Act of 1998 stipulates that the government grant timber rights in the form of Timber Utilization Contracts and change all previous timber rights into TUCs (GOG Concession Act 1962; Hansen and Treue 2008).

There are six classifications of forests in Ghana: private/individual plantations, community plantations, instructional plantations, communal forests, forest reserves, and off-reserve forests. Generally forest tenure is tightly tied to customary land tenure. However, even customary “owners” of land are not allowed access to forest reserves unless they have proper documentation and permits from the GOG’s Forestry Services Division. Some classifications of forests can be used by local households for fuelwood and food- and medicine-gathering, including communal forests. Customary rules governing forest tenure give fewer rights to immigrant and tenant farmers (Boakye and Baffoe n.d.).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSITUTIONS

The Forestry Commission is a semi-autonomous agency that replaced the former Forestry Department, brought all relevant public agencies under the same structure and streamlined forest management services. The Commission regulates forest reserves and protected areas, monitors timber harvests, advises on technical issues of forest protection and conservation, and works with private entities on forest management and conservation issues (including the development of forest plantations and game ranches). The Commission houses several divisions: the Timber Industry Division; Wildlife Division; Forest Services Division; Wood Industries Training Centre; and the Resource Management Support Center. Under the 1962 Concession Act and the 1992 Constitution the concessions gained by government are shared with stools and local government (FAO 2004; GOG 1994).

The purpose of the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources is to sustainably manage Ghana’s wildlife and forest resources for economic growth and development of the nation. The Ministry is meant to liaise between customary landowners and the national governments, promote local communities’ participation in forest management, develop capacity in the public sector, and review national forest policies and law (GhanaWeb 2011; GOG 2011a).

The Forestry Development Master Plan (FDMP), effective from 1996 to 2020, was developed as a tool to support the realization of goals laid down in the Forest and Wildlife Policy of 1996. The goals included the conservation and sustainable development of Ghana’s forests and wildlife to ensure environmental quality and broad-based enjoyment of resources. In particular, because the government has been unable to manage demand for domestic timber through implementation of the Forest and Wildlife Policy, resulting in deforestation, the Ministry of Lands and Resources and the Forestry Commission have used and begun to review the Forestry Development Master Plan as a means to address shortcomings in the policy. Among other things, a Policy Review Committee has been established to develop proposed potential amendments that incorporate stakeholders interests (Tropenbos International 2010).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The Natural Resources Management Programme is coordinated by the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources and funded by donors including the Government of Ghana, the European Union (EU), DFID, the World Bank, the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), and the Netherlands Development Assistance (NEDA). The program seeks to support local communities who make a living from the forests (FAO 2004).

The National Forestry Development Programme was instituted in 2001 with the purpose of planting 20,000 hectares of forests through cooperation with private entities (including agro-forestry enterprises) (FAO 2004).

The Community Forestry Management Project, started in 2003 by the government, focuses on supporting community forestry. One activity under this project was the engagement of farmers in the planting of teak plantations and other livelihood activities in degraded forest reserves (FAO 2004; Ghana News Agency 2010b).

The GOG in partnership with the EC, the Royal Netherland Government, AFD, DFID, and IDA developed the Natural Resources and Environmental Governance Programme (NREG). The NREG seeks to decrease illegal logging, lessen conflict related to mining and forestry, and improve public-sector resource management within the sector (GOG 1994).

The GOG has also funded a program to conserve and rebuild forests outside of nationally protected areas. This program has the goal of employing youth to reforest 30,000 hectares annually (GOG 1994).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The FAO, together with GTZ and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation, have supported Ghana in becoming the first country to adopt the UN’s Forum on Forests’ Non-legally Binding Instrument on All Types of Forests, otherwise known as the “Forest Instrument.” The Forest Instrument contains 24 policies and actions to be implemented nationally, representing a wide range of measures geared toward achieving sustainable management of the forests (UNFF 2010).

The Forest Resources Management Project (FORUM) is funded by GTZ and KfW. With a budget equivalent to approximately US $320,000, FORUM seeks to rehabilitate, rebuild and protect forests and woodlands. FORUM was completed in 2008 (GOG 1994; OANDA 2011).

The United States Forest Service has been collaborating with USAID and the World Wildlife Fund to “address biodiversity loss in productive forest concessions” by building local capacities, supporting Sustainable Forest Planning Reform, and improving wildfire responses (USFS 2011).

Minerals

RESOURCES QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Mineral resources extraction has existed in Ghana for centuries, although until recently only in the form of small-scale mining. Ghana has many minerals, including manganese, gold, diamonds, bauxite, aluminum, natural gas, petroleum, silver and salt. Most of these mineral deposits are concentrated in the southern third of the country. Ghana has 15 million barrels of proven oil reserves, and an estimated five billion barrels of projected oil reserves (USGS n.d.; Bermúdez-Lugo 2005; Harkinson 2003; CIA 2011; McLure 2010).

Mining is of great importance to Ghana’s economy. Mineral exports constitute 30% of total exports, make up 5% of Ghana’s GDP, and constitute nearly 4% of the national government’s revenues. However, only 5% of the US $894 million earned by mining corporations in Ghana in 2003 remained in Ghana (Bermúdez-Lugo 2005; Oxfam International 2011).

Mining has had many negative impacts on local communities in Ghana, and on the country’s forests. Currently 30% of Ghana’s territory is under gold mining firms’ concessions, and that percentage continues to grow, with agricultural land diverted to mineral extraction. Land has been taken from farmers, often without compensation, and sometimes under violent circumstances. In 2006 the BBC reported that confrontations between police, mine security and local people had resulted in a number of deaths. Mines also leach toxic chemicals into drinking water (IRIN 2009; Oxfam International 2011; Oxfam America 2011; World Rainforest Movement 2004; Harkinson 2003).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The new Minerals and Mining Act (Law No. 703) of 2006 gives the State full ownership of all minerals; and gives the government full authority to occupy and use land for mining. Specifically, the law authorizes the government to compulsorily acquire or occupy land that is deemed necessary to develop or utilize mineral resources, although it requires fair, adequate and prompt compensation to the land rights holder (GOG Minerals and Mining Act 2006).

The Law also establishes a mineral rights cadastral system, defines the term limits of mining leases, and gives the State ownership of all minerals. The Law states that rights will be given “on [a] first-come, first-considered basis,” and mining leases will be allocated for 30 or fewer years with the possibility of renewal for 10 years. The law has been criticized for not adequately protecting local communities against mining interests and impacts, and for the powers it gives the State for compulsory acquisitions (GOG Minerals and Mining Act 2006; AllAfrica 2010).

The Diamonds Act of 1972 obligates anyone who finds a diamond to sell it to the Diamond Marketing Corporation within four weeks with documentation. The Act empowers the Ministry of Internal Affairs to regulate “diamond areas” by excluding access to those areas and granting permits of access. The Act also describes the process for obtaining status as a licensed diamond buyer (GOG Diamonds Act 1972).

The Small-Scale Gold Mining Act of 1989 establishes Small Scale Gold Mining Committees to assist in the regulation and monitoring of local small-scale gold mining. It also requires that anyone who sells gold must be licensed. According to the Act, if a mining license is given to someone other than the landowner, the licensee must compensate the landowner as directed by the Land Valuation Board and Minerals Commission (GOG Small-Scale Gold Mining Act 1989).

TENURE ISSUES

While the government owns all minerals in Ghana, corporations can apply for reconnaissance and prospecting licenses to search for specific minerals. The reconnaissance license is granted for one year, and can be granted for up to 1050 square kilometers. A prospecting license grants exclusive rights for searching for minerals. This license allows the holder to excavate and drill to reveal the value and amount of deposits within the license area. These licenses are given for up to three years and for 26.3 square kilometers (Ghana Mining 2011).

The Minerals Commission can grant mining leases for mining rights to specific minerals in a defined geographic area. These leases are issued for thirty years, limited to 63 square kilometers. About 12% of all land in Ghana is currently under some form of concession for mineral exploration. One study showed that within mining concessions of Western Ghana’s Wassa West District, an area covering 19,300 hectares, forestland has decreased by 58%, while farmland has decreased 45%. (Ghana Mining 2011; Schueler et al. 2011).

Small-scale mining licenses are granted to cooperatives, groups, companies or individuals. The rights granted by this license exclude mining of certain minerals, and can only be granted for a 10-hectare area (Ghana Mining 2011).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources provides oversight of the mining sector, and is responsible for granting licenses for exploration and mining activities (GOG 2011b).

The Minerals Commission was established in 1992, and is the government’s primary mining regulatory agency (Ghana Mining 2011).

The Land Valuation Board and Minerals Commission determine the amount of compensation mining licensees must pay landowners (GOG Minerals and Mining Act 2006).