Published / Updated: August 2010

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

Malawi is a small country, heavily dependent on agriculture, with a rapidly growing population. At independence in 1964, Malawi’s land was designated as under private freehold, public, or customary ownership. The private land, often acquired in the colonial era through alienation of customary land, was used for large-scale production of export crops, such as tea and tobacco. These “estates” became the property of the Malawian elite, and throughout the 30-year tenure of Malawi’s first president, Kamuzu Banda, production continued much as it had under colonial rule. Given the importance of their production for national trade revenues, estates were favored in agricultural policy while Malawi’s smallholder farmers were restricted to producing crops for local consumption. A policy change in 1990 allowed smallholders to grow and market bey tobacco, by then the dominant export crop, but these farmers’ access to land remained constrained. By 2000, it was estimated that more than 55 % of small farm families had less than one cultivable hectare.

Following critical democratic elections in 1994, the government took the first steps toward addressing the increasingly inequitable land situation and established a Presidential Commission of Inquiry on Land Reform. The Commission was tasked with establishing the principles for a new land policy that would be more economically efficient, environmentally sustainable (as much of the estate land was not fully used, and overused small farms were experiencing land degradation), and socially equitable. The Commission’s findings were used to form a new land policy, but subsequent efforts to develop legislation and an enabling land administration have not yet come to fruition. A Community-Based Rural Land Development Programme was launched in 2004 with World Bank (and other donor) support to pilot the use of market mechanisms to help land-short farm households secure larger acreages by purchasing uncultivated and/or underutilized estate land (estimated at 600,000 hectares). While the pilot met its goals of resettling 15,000 farm households, it did not spark spontaneous expansion of the approach. The new settlers were dependent on the additional public financing provided to facilitate their relocation, and the political support of traditional leaders was not always achieved.

At the same time, Malawi’s President Mutharika has taken steps to increase smallholder production of maize, the country’s staple food, by subsidizing the provision of fertilizer to smallholders. This has been viewed as widely successful in increasing productivity (and total food production in the country) but many question whether this approach will compensate for the land resource access and management issues that remain unresolved for Malawi’s 1.8 million farm households. Donors to Malawi are, therefore, likely to continue to confront thorny issues of land access, tenure, and resource management as they support the country’s strategies to reduce poverty and increase food security.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

The lessons of the pilot Community-Based Rural Land Development Programme need to be reviewed to shape further initiatives for rural-rural resettlement, addressing issues of local governance, gender equity, the provision of complementary support services, and overall market development for agriculture. Development of laws and regulations on leasing of land might be another approach to improve land access. Donors will need to collaborate closely on these issues going forward, to ensure that solutions to problems that have emerged in the pilot program are well-designed and consistently applied.

The Government of Malawi has focused in recent years on the provision of fertilizer at substantially subsidized prices tofacilitate greater production of rainfed maize on smallholder farms. Early success has enhanced the government’s commitment to this intervention, in spite of the significant budgetary costs. Expansion of irrigation systems and diversification of production for both domestic and export markets, however, also offer options for greater intensification of production and income-earning opportunities for smallholder farmers. More sustainable exploitation of wetlands might be a particular area of focus. A more consistent, market-sensitive policy framework is needed to increase incentives and reduce risks for investors, service providers, and market agents as well as small farmers. Donors already provide significant support in the sector but further coordination on sector policy and approaches to greater market development would be helpful.

that will fully support the Government’s goals for economic growth and poverty reduction, while ensuring that the rights of rural women, especially those heading households, are fully recognized. Given the complexity and diversity of customary tenure systems in Malawi, detailed assessments may be necessary to ensure that systems unique to one area or population group are adequately addressed in broader legislation and that the role of local, traditional governance structures is clarified. Donors can support the analytical and consultative processes that could help to advance efforts to establish a system of property rights and resource governance that both promotes growth and protects individuals’ rights as guaranteed by the Malawian Constitution.

Summary

Malawi is a densely populated country with one of the lowest GDPs per capita in the world. Malawi’s population suffers from chronic food insecurity, land degradation and pervasive poverty. Land distribution is highly skewed. The vast majority of Malawi’s agricultural sector is made up of farmers cultivating small, rainfed plots to grow food for consumption. A relatively small number of large commercial estates on irrigated land grow high-value crops for export. Malawi has potential to increase the amount of irrigated land, and the Government of Malawi (GOM) has been investing in small-scale irrigation schemes to support expanded and increased production of food crops like rice.

In 1995, the GOM undertook ambitious efforts toward land reform that led to the passage of the National Land Policy in 2002. The policy calls for the redistribution of land from large estates to smallholders, formalization of customary tenure to address tenure insecurity, and creation of a commission to review and revise existing land legislation. Some elements of the land reform program have shown positive results in pilot programs, but a land law implementing the 2002 Land Policy has not yet been enacted and the pace of reform has been slower than hoped.

Deforestation is occurring at a rapid rate and is attributed to agricultural expansion, demand for fuelwood, charcoal production, and income-generation activities such as tobacco curing and brick burning. Implementation of the GOM’s progressive policy and guidelines for local management of forest resources has been limited to a handful of projects, which have shown some success. Lack of funding and institutional capacity-building have constrained the expansion and institutionalization of community-based programs.

Deforestation is occurring at a rapid rate and is attributed to agricultural expansion, demand for fuelwood, charcoal production, and income-generation activities such as tobacco curing and brick burning. Implementation of the GOM’s progressive policy and guidelines for local management of forest resources has been limited to a handful of projects, which have shown some success. Lack of funding and institutional capacity-building have constrained the expansion and institutionalization of community-based programs.

Large reserves of coal and other mineral deposits have been identified in Malawi in the last decade, and the GOM has identified the mining sector as a priority area for growth. The GOM has drafted a new mining policy and law and is developing a comprehensive strategy to adopt and implement the new legal framework and create a sustainable regulatory environment to encourage responsible development of the sector. Civil society has proved to be an active force in enforcing obligations for environmental impact assessments and plans to rehabilitate mining sites.

Land

LAND USE

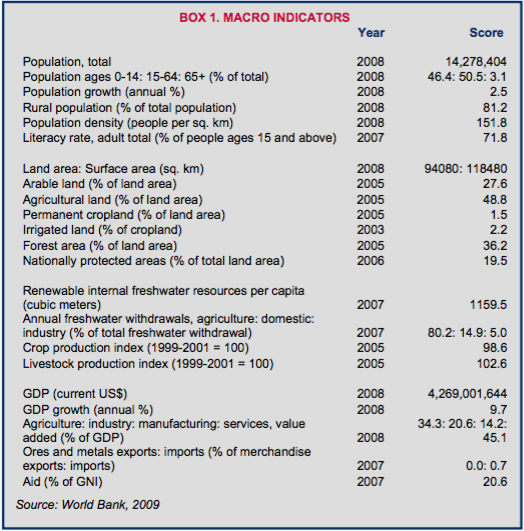

Malawi’s population of 14 million people is 81% rural and 19% urban. Malawi is one of the more densely populated countries in Africa, with an average of 103 inhabitants per square kilometer; population density is highest in the south and central regions. Malawi’s total land area is 94,100 square kilometers, of which 49% is agricultural land. Approximately 2% of Malawi’s cropland is irrigated. Agriculture – especially tobacco, tea, and sugar – currently contributes more than 80% of the country’s export earnings. Malawi’s total gross domestic product for 2008 was US $4.3 billion, derived from agriculture (34%), industry (20%), and services (45%) (World Bank 2009a; World Atlas 2010; Chirwa 2004; Chirwa and Chisinga 2008).

Approximately 30,000 farms are of relatively large scale (10–500 hectares) and focus on the production of cash crops, with bey tobacco presently leading export earnings. These “estates” were formed during colonial times, were controlled by white farmers, and included large tracts of underutilized land. The estates had the privileged right to produce the crops for export while smallholders were required to sell their crops at lower prices to a marketing board. At Independence in 1964, ownership of the estates passed into the hands of the Malawian elites. The autocratic Banda regime (Independence to 1994) reinforced the colonial-era dual structure of an agricultural sector made up of large estates and smallholders. At that time, agricultural policy was aimed at sustaining the productivity and export income generated on these properties. The conversion of customary land (held by various ethnic groups) to leasehold land used for commercial faming also characterized this period (Chirwa 2004; Chirwa and Chisinga 2008; Holden et al. 2006).

Approximately 30,000 farms are of relatively large scale (10–500 hectares) and focus on the production of cash crops, with bey tobacco presently leading export earnings. These “estates” were formed during colonial times, were controlled by white farmers, and included large tracts of underutilized land. The estates had the privileged right to produce the crops for export while smallholders were required to sell their crops at lower prices to a marketing board. At Independence in 1964, ownership of the estates passed into the hands of the Malawian elites. The autocratic Banda regime (Independence to 1994) reinforced the colonial-era dual structure of an agricultural sector made up of large estates and smallholders. At that time, agricultural policy was aimed at sustaining the productivity and export income generated on these properties. The conversion of customary land (held by various ethnic groups) to leasehold land used for commercial faming also characterized this period (Chirwa 2004; Chirwa and Chisinga 2008; Holden et al. 2006).

Small farms are responsible for most of Malawi’s agricultural production. Most of the country’s 2 million small farmers cultivate less than one hectare of rainfed land. While some grow crops for exports, most are subsistence farmers. An estimated 70% of land cultivated by small farmers is devoted to maize. Low levels of on-farm productivity combined with poorly developed input/output markets caused chronic food insecurity; malnutrition affected 35% of the population in 2007 (Chirwa 2004; World Bank 2009b; World Bank 2007a).

Forest land comprises 36% of the total land area. Nineteen percent of the country’s total land area is protected. Deforestation is occurring at an annual rate of 0.9% (World Bank 2009a).

Malawi is rich in wetlands, the cultivation of which is increasingly important to people’s livelihoods, especially as periods of drought increase in frequency and length. In Malawi, wetlands are defined as permanently or seasonally wet lands located in valleys, depressions or floodplains, and therefore less susceptible to drought. Those with access to and ownership of wetland gardens have an advantage in terms of food availability. Stream- bank gardens are also significant sources of food for smallholders and for informal irrigation (FAO 2006; Kambewa 2005; Peters 2004).

High annual population growth (2.1%) combined with a limited land base and few fallow periods have led to soil erosion, severe deforestation, pollution of water resources, and general degradation of the natural resource base. Wetlands are similarly threatened by degradation (FAO 2006; Mvula and Haller 2009; Ferguson and Mulwafu 2004).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Malawi’s land distribution is highly skewed. An estimated 82% of Malawi’s land is suitable for cultivation: 13% of total land (16% of cultivable land or 1.2 million hectares) is held by estates, and 69% of total land (84% of cultivable land or 6.5 million hectares) is either farmed by smallholders or considered by the government to be available for smallholder farming. The balance of Malawi’s land is protected areas, steep hillsides, and urban areas unsuitable for agriculture. Fifty-eight percent of smallholders cultivate less than one hectare; 11% of these are near landless. The country’s 30,000 estates have between 10 and 500 hectares. In 2004, approximately 11% of the population was landless (Chirwa 2004; Chirwa and Chisinga 2008; GOM 2002; Adams 2004; World Bank 2009b).

Rural households hold between one to ten plots, with an average of two plots per household. The small, fragmented landholdings that characterize the agricultural sector are a holdover from colonial times. Colonialists created large estates, which had the privileged right to produced the most valuable crops for export. Smallholders produced food for consumption and were required to sell their crops at lower prices to a marketing board. The autocratic Banda regime (Independence to 1994) reinforced the dual structure of an agricultural sector made up of large estates and smallholders. Large estates added to their holdings through the conversation of some 700,000 hectares of customary land into leaseholds (Chirwa 2008; Peters and Kambewa 2007; Walker and Peters 2001; Cross 2002; Takane 2007a).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1994 Constitution of the Republic of Malawi provides that all of Malawi’s land is vested in the state. Under the Constitution, all citizens have the right to obtain property and to engage in economic activity (GOM 1994).

Malawi’s land legislation dates primarily from the post-Independence era and includes: (1) the 1965 Land Act, which sets out the classifications of land and recognizes types of land tenure; (2) the 1967 Customary Land (Development) Act, which provides for the conversion of customary land for agricultural development and establishes the means for adjudicating disputes over customary land; (3) the Deeds Registration Act, which supports a system of deed registration; (4) the 1967 Registered Land Act which provides the legislative foundation for the transfer from a deed registration system of land administration to a title registration system; (5) the 2003 Land (Amendment) Act, which prospectively prohibits non-citizens from purchasing land in Malawi; and (6) The 1989 Control of Land (Agricultural Leases) Order (amended in 1996), which introduced a prohibition on conversion of customary land to leaseholds. Implementation of the Customary Land (Development) Act and the Registered Land Act has been limited to Lilongwe West (CEPA n.d.; Cross 2002; Ngwira 2003; GOM 2002; Holden et al 2006).

The 2002 National Land Policy was an initial step in revising the legal framework governing land rights. The Land Policy expressed the goals of ensuring tenure security and equitable access to land, and facilitating the attainment of social harmony and broad-based social and economic development through optimum and ecologically balanced use of land and land-based resources. The Land Policy’s objectives are to (1) promote tenure reforms that guarantee security and instill confidence and fairness in all land transactions; (2) guarantee secure tenure and equitable access to land to all citizens of Malawi without any gender bias or discrimination; (3) instill order and discipline into land allocation and land market transactions to curb land encroachment, unapproved development, land speculation and racketeering; (4) promote decentralized and transparent land administration; (5) extend land-use planning strategies to all urban and rural areas; (6) establish a modern land registration system for delivering land services to all; (7) enhance conservation and community management of local resources; and (8) promote research and capacity-building in land surveying and land management (GOM 2002).

In 2003, a Special Law Commission formed to draft a new land law implementing the 2002 Land Policy. The draft land bill was withdrawn from consideration by the National Assembly in 2007. In 2009, in part to assist the government in enacting a new land law, the World Bank requested an extension of its land reform project (to 2011) (CEPA n.d.; World Bank 2009b).

Customary law governs land allocation, land use, land transfers, inheritance, and land-dispute resolution related to Malawi’s customary land. The 2002 Land Policy recognizes the authority of customary law and traditional authorities and calls for incorporation of the traditional authorities into the land-administration structure (Chirwa 2008; UNEP/UNDP 2001; GOM 2002).

TENURE TYPES

Malawi’s 1965 Land Act and the 2002 Land Policy recognize three categories of land: public land, private land, and customary land.

Public land (including government land) is land occupied, used, acquired, or held by the government in the public interest. Public land includes national parks, conservation, and historical areas. Government land is owned and used by the government for public purposes, including schools and government offices. Public land vests in perpetuity in the President, as trustee for the government. Between 15% and 20% of land in Malawi is classified as public land.

Private land is owned, held or occupied under freehold title, lease, Certificate of Claim, or land registered as private land under the Registered Land Act of 1967. According to the Land Policy, land registered as private land under the Registered Land Act includes privately owned freehold land and customary land registered by communities or individuals (upon registration, the land loses its character as customary land). Between 10% and 15% of land in Malawi is classified as private land.

Customary land is all land held, occupied, or used by community members under customary law. Customary land is vested in the President in trust for the people of Malawi and is under the jurisdiction of customary traditional authorities. Customary land may be held communally or individualized in the names of a lineage, family, or individual. Customary land does not include public land. Between 65% and 75% of land in Malawi is customary land (Chirwa 2008; CEPA n.d.; UNEP/UNDP 2001; GOM 2008; GOM 2002; Niyoka 2003).

Tenure types in Malawi include freehold, leasehold, and customary tenure:

Freehold. Private land can be held in freehold tenure, which carries rights of exclusivity, use, and alienation. The 1965 Land Act and the 1967 Registered Land Act regulate the use and management of freehold land. Most freehold rural land consists of large-scale commercial plantations or estates. Some of the land was customary land that the government converted to freehold land at Independence in an effort to encourage agricultural development (UNEP/UNDP 2001; CEPA n.d.; Holden et al. 2006).

Leasehold. Private, public, and customary land can be leased. An estimated 8% of Malawi’s land is under leaseholds governed by the Land Act. Lease terms vary by use, including 21-year leases on agricultural land and 22- to 99-year leases for property and infrastructure development. Under the Land Act, the state has the authority to lease customary land and public land. Formal leases of customary land result in the conversion of the customary land to public land because, at the conclusion of the lease, the land reverts back to the government. Under customary law, landholders may lease their land without causing the land to lose its character as customary land. An estimated 28% of the rural population is engaged in the land rental markets as landlords or tenants; the majority lease land under customary law (UNEP/UNDP 2001; GOM 2008; Lunduka et al. 2009; Mbalanje 1986).

Customary tenure. Land held under customary tenure is held by a group as a whole, usually administered by a traditional leader on behalf of the community. Customary land may be individualized in the names of families and individuals. Land that has been individualized carries a presumption of exclusive use in perpetuity, and the family or individual can lease the land or bequeath it. The National Land Policy provides that the community retains a residual interest in the land, suggesting that the land cannot be sold outside the community. Traditional leaders may reclaim and reallocate land if it is abandoned. Land that is not individualized (e.g., grazing land, markets, burial grounds) is considered communal land with customary law dictating rights of access (GOM 2008; Takane 2007a; Matchaya 2009; Chirwa 2008).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Malawians primarily access land through inheritance (52%) and marriage (18%). Rights to land through marriage and inheritance are governed by one of two customary systems. Under the matrilineal system prevalent in the central and southern regions of the country, land is handed down through the female line. If the husband moved to the wife’s village at marriage, he generally loses rights to use the household land in the event of divorce or his wife’s death. Under the patrilineal system prevalent in the northern region, land is transferred from fathers to sons. If a woman moves to her husband’s village at the time of marriage, she often loses rights to use the household land in the event of divorce or the death of her husband (Matchaya 2009; UNEP/UNDP 2001; Chirwa 2008).

Land allocations from traditional leaders, land leasing, government resettlement programs, and land purchase are additional routes to access land. An estimated 20% of landholders obtain land from traditional authorities; roughly 1% of landholders obtain land through purchase. Leases, government land programs, and other means account for the remaining percentage (9%). In urban areas, Local Assemblies and agencies such as the Malawi Housing Corporation allocate plots in the areas within their jurisdiction (Kambewa 2005; Matchaya 2009; Chirwa 2008; GOM 2002).

While most holders of customary land believe their rights are reasonably secure, tenure insecurity is evident among a few social groups. Both women of patrilineal and virilocal (wife moves to husband’s village) marriages and men of matrilineal and matrilocal (husband moves to wife’s village) marriages express insecurity when considering the potential death of their spouse or the possibility of divorce, because they and their children may be forced to leave the land. The high prevalence of HIV/AIDS among the adult population exacerbates the degree of insecurity that a spouse may experience. Orphans also have insecure property rights; relatives often take the deceased parents’ land, dispossessing the children (Mbaya 2002; Ngwira 2003; Takane 2007a; Holden et al. 2006; Matchaya 2009; Chirwa 2008).

Tenure security is lowest for women in patrilineal societies, men in matrilineal groups, and orphans. Other groups expressing tenure insecurity are non-citizens and some recipients of land programs and irrigation schemes where the beneficiaries do not receive land title. The 2002 National Land Policy recognizes the importance of tenure security. In order to protect against arbitrary conversion to public or private land and permanent loss of customary land rights, the 2002 National Land Policy recommends surveying and recording customary land. The Land Policy also notes that local governments should be required to identify existing customary land rights as part of developing land-use plans (Holden et al. 2006; GOM 2002).

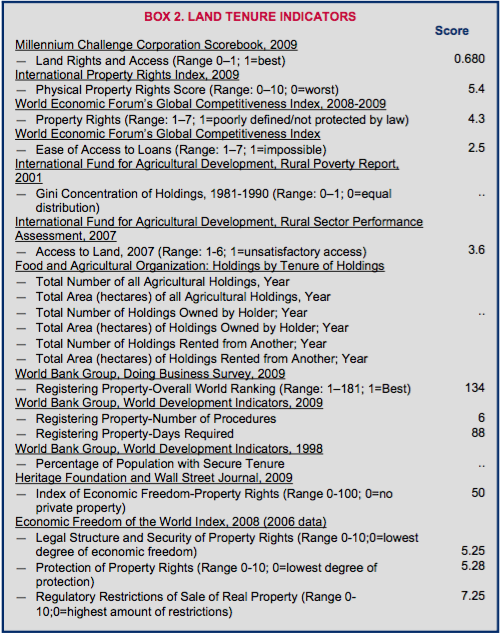

During colonial times, Malawi adopted a deeds registration system. The system provided for the registration and public availability of documents relating to land rights but no assurance of the validity of the registered documents. The deeds registration system is governed by the Deeds Registration Act. The procedure for registering the transfer of land is as follows: (1) search for encumbrances on the land at the land/deeds registry; (2) search for unpaid city taxes at the municipality; (3) apply to the Ministry of Lands for consent to transfer property; (4) obtain a Tax Clearance Certificate from the Malawi Revenue Authority; (5) obtain a stamp of the conveyance deed and relevant documents at the Registrar General’s Office; and (6) apply for registration at the Deeds Registry. Land registration requires an average of 88 days and payment of 3.2 % of the value of the land. A small number of deeds are registered (GOM 2002; World Bank 2008).

In an attempt to convert to a system of title registration (because the deed registration system did not protect against registration of inaccurate and fraudulent documents, and thus did not provide for certainty in land transactions), the government enacted the Registered Land Act in 1967. The Registered Land Act confers substantive land rights: under Section 24 of the Act, registration of land confers private ownership rights on the registered proprietor. The Act allows for registration of customary land as “family land” with a designated registrant. Registration of customary land converts the land to private land. Leasehold interests can also be registered. The land certificates and certificates of lease issued by the Land Registry Office are proof of those interests in land and are guaranteed by the state (Mbalanje 1986; GOM 2002; World Bank 2008).

The Registered Land Act was implemented in only one region (Lilongwe West) under the Lilongwe Land Development Programme (1968–1981). Lack of institutional support and funding for the titling and registration system limited its implementation. The 2002 Land Policy reasserts the government’s interest in a title registration system, calling for the transfer of registered deeds to the title registry system, and demarcation and formalization of individualized rights to customary land (referred to as “customary estates”) (GOM 2002; Holden et al. 2006).

Historically there was no restriction on foreigners purchasing freehold land in Malawi. The 2003 Land (Amendment) Act caps the amount of freehold land held by foreigners as of January 2002 and prospectively prohibits foreign individuals and companies from acquiring title to any freehold estate. Foreigners are permitted to lease land (GOM 2002; CEPA n.d.).

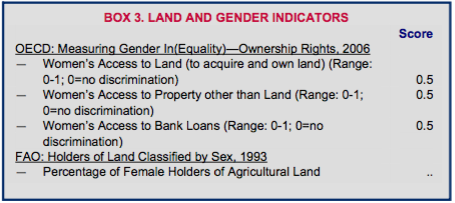

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Under Malawi’s formal law, women and men have the right to own land, individually or jointly with others, and the Constitution prohibits gender discrimination. However, cultural biases often prevent women from enjoying equal access, control, and ownership of land (Mbaya 2002; Ngwira 2003).

Under Malawi’s formal law, women and men have the right to own land, individually or jointly with others, and the Constitution prohibits gender discrimination. However, cultural biases often prevent women from enjoying equal access, control, and ownership of land (Mbaya 2002; Ngwira 2003).

The 2004 Deceased Estates (Wills, Inheritance and Protection) Act allows individuals to draft wills that transfer all their interests in their property. If an individual does not have a will or does not dispose of all of his or her property by will, the property will go to providing for the the deceased’s immediate family. The law also provides that a surviving spouse is entitled to his or her household belongings. Any remaining property shall be passed to the surviving spouse and children, with evidence taken relevant to the shares granted, such as the wishes of the deceased and the need to educate children. If no special circumstances are noted, the law requires equal shares (GOM 2004b).

For most Malawians, land ownership and inheritance are governed by customary law and traditional practices. Both matrilineal and patrilineal systems exist. Matrilineal systems of marriage and inheritance are prevalent in the southern and central regions of Malawi where certain ethnic groups dominate. In most matrilineal systems, either the man moves to the woman’s village and lineage is traced through the women, or the woman goes to live in the man’s village but the children belong to the woman’s lineage (Mbaya 2002; Ngwira 2003; Holden et al. 2006).

The north is home to ethnic groups that embrace patrilineal customs. Under the patrilineal system, the man’s village becomes the marital home, and he pays a bride price to the bride’s family. Women do not own property and only the sons, not daughters, inherit property. Payment of bride price leads many men to believe they own their wives and children and that, when they die, their spouses and children become the property of the man’s family (Mbaya 2002; Ngwira 2003; Ligomeka 2003).

Approximately 25% of households are headed by women, and 63% of rural women-headed households live below the poverty line. Typically, women-headed households possess smaller landholdings and fewer livestock than their male counterparts, and they produce significantly less maize, the main food crop. Widows are vulnerable to property-grabbing by their husbands’ relatives (Takane 2007b; White and Malunga 2006; Ngwira 2003).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

In 1997, the Ministry of Lands and Valuation, Ministry of Physical Planning and Surveys, Ministry of Housing. and the Department of Buildings in the Ministry of Works and Supplies merged to create the Ministry of Lands, Housing, Physical Planning and Surveys. The Ministry is the primary agency responsible for land and housing in Malawi. The Ministry’s mission is to provide efficient and effective land services and promote and encourage sustainable management and utilization of land and land-based resources. The Ministry of Irrigation and Water Development is responsible for managing irrigation systems for agricultural land (GOM 2009b; GOM 2003).

The Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security’s mission is to ensure food security, increased incomes, and creation of employment opportunities by promoting and facilitating agricultural productivity. To that end, the Ministry’s responsibilities are to: (1) attain and sustain household food self-sufficiency and to improve the population’s nutrition; (2) expand and diversify agricultural production and exports; (3) increase farm incomes; (4) conserve the natural resources; (5) formulate agricultural policies; (6) draft legislation and regulations with stakeholder participation; (7) generate and disseminate agricultural information and technologies; (8) regulate and ensure quality control of agricultural produce and services; and (9) monitor and manage food security (GOM 2009a).

The Department of Environmental Affairs within the Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Environmental Affairs is focused on preventing environmental degradation, including soil erosion, threats to biodiversity, human habitat degradation, and air pollution; the Department is also responsible for the protection of wetlands (GOM 2010).

At the local level, traditional authorities are responsible for allocating customary land and ensuring that land is passed by customary laws of inheritance. Chiefs tend to rely on clan and family leaders to identify and actually allocate pieces of land to individuals and households from land owned by that group. Once allocated, the family land is held and managed by the family. The Land Policy envisions a decentralized system of land administration in which local and district-level offices are responsible for land administration, and the roles of traditional authorities are formalized in bodies such as a Customary Land Committee and Traditional Land Clerks (GOM 2002; Mbaya 2002; UNEP/UNDP 2001).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Access to land for cultivation in Malawi has become more restricted, especially in areas with productive land. Pressure on land access is caused by the arrival of newcomers in need of land (often drawn by migration away from degraded areas and to areas of more productive land, such as after development of irrigation), volatility of weather patterns, growing demand for food from increasing population in urban and peri-urban areas, and greater diversification in family income strategies (Peters and Kambewa 2007; Holden et al. 2006).

The increased pressure on land has increased the individualization of ownership for customary land and former open-access areas; transactions in land are common. Sales of customary land are usually limited to transfers within families or communities. People sell land when they need cash, have more land than they can cultivate, or have no heirs interested in farming. Sales are most common in areas of commercial development, such as along roads and near market places, and sales tend to occur among wealthier farmers selling to non-family members. There are also reported incidents of traditional authorities selling rights to desirable land to outsiders and commercial interests (Holden et al 2006; Peters and Kambewa 2007).

In the Lilongwe West where the Lilongwe Land Development Programme was implemented, customary land was registered in the name of lineages. One recent study reports that the area has an active land sales market and the value of land is increasing. Transactions costs are high: payments to three levels of headmen and to the traditional authority for his or her required signature almost triple the price of the land (Holden et al 2006; Peters and Kambewa 2007).

Most land transactions in Lilongwe West occur between relatively wealthy landowners. The 2005 World Bank- supported land-purchase program, the Community-Based Rural Land Development Project, used a community- driven approach to provide landless and land-poor households with access to land through the land sales market. Beneficiaries organized themselves into small groups, identified land for purchase, and negotiated for the land. The project subsidized the land purchase and some development costs for 15,000 beneficiary households. The project was extended in 2009 to 2011 in order to provide support for beneficiary families and help resolve policy issues that hinder the development of land markets. These issues include: (1) collection of land rent; (2) introduction of a land tax on freehold land; and (3) enactment of a new land law (Holden et al. 2006; World Bank 2009b).

Malawi also has an active land rental market, which is the most common avenue for land-poor households to access land. An estimated 28% of landholders are participating in the land rental market as landlords or tenants, with participation as high as 90% of households in some areas (Peters and Kambewa 2007; Lunduka et al. 2009; Holden et al. 2006). Malawi’s 2002 Land Policy calls for the adoption of legislation that will protect against fraudulent transactions involving customary land, control land-speculation in customary land, and protect against unintended landlessness. Recommended safeguards include requiring written approvals of the landowning group, chief, and independent member of a customary land committee for all transfers of customary land, and prohibiting sales of customary estates outside the immediate family during the first five years of titling (GOM 2002).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The 1995 Constitution of the Republic of Malawi mandates that no person shall be arbitrarily deprived of property; the state can expropriate land only for public utility and only when the state has given adequate notification and provided appropriate compensation. Compensation shall be paid based on the open market value of the land and any improvements (GOM 1995; GOM 2002).

The Land Acquisition Act sets forth the procedural protections guaranteed by the Constitution when land is to be acquired by the government, individuals, or developers. Valuation of assets such as buildings, trees, fruit trees, crops, and vegetables are provided for in the Public Roads Act and the Town and Country Planning Act. The Ministry of Land and Natural Resources has established compensation schedules for agricultural produce, physical assets, and trees, each with its own methods of valuation. The methods are dated and suffer from undervaluation of assets and underpayment of compensation to affected persons (GOM 2008)

In World Bank-funded projects that require land-acquisition and resettlement, project resettlement and compensation plans exceed legal requirements. The projects consider a broad range of land occupants as holding land rights that must be compensated, value all type of land tenure equally, compensate people for illegally-built structures, provide land as a preferred option over compensation for all classes of landholdings (including urban), and provide more extensive relocation assistance (GOM 2008).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Disputes over land most commonly occur over land transactions, land access, and inheritance rights. Due to the fluctuations in weather patterns and the vulnerability of the country to drought, land along water sources and wetlands is commonly the subject of disputes. In peri-urban areas, land conflicts between long-term occupants and migrants are common. Most disputes are handled by traditional leaders (Peters and Kambewa 2007; Kambewa 2005; Mbaya 2002; Kandodo 2001; Adams 2004; Holden et al. 2006).

Traditional courts are recognized under the Constitution. Traditional courts have jurisdiction over civil cases brought under customary law, and minor common law and statutory civil cases as prescribed by statute. The Land Policy proposes a land-conflict resolution system managed by district and traditional authority land tribunals. A Village Tribunal hears land disputes in the first instance, with appeals to a Group Village Tribunal, then a Traditional Authority Land Tribunal, followed by a district-level tribunal. Appeals from the district-level tribunal are sent to a Central Land Dispute Settlement Tribunal, with a right to appellate review at the High Court (Holden et al. 2006; Kandodo 2001; Kapindu 2009; GOM 2002).

Within the formal court system, the magistrate courts are the courts of first instance for most civil and all criminal matters. Issues arising relating to private land rights held under formal law must be brought in the formal court system (Reynolds and Flores 2009).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The government recognizes the need to enhance the productivity of smallholder farmers as a means for achieving the agricultural growth and poverty-alleviation goals of the Malawi Growth and Development Strategy (MGDS) being implemented from 2006 to 2011. The MGDS targeted agriculture as a driver of economic growth and recognizes that food security is a pre-requisite for economic growth and poverty alleviation. Malawi’s agricultural development strategy has four major objectives: (1) increase the productivity and diversity of food crops in the smallholder sub-sector; (2) promote tobacco production in the smallholder sub-sector to boost incomes; (3) promote crop diversification; and (4) promote the expansion of the livestock sector and its integration with mixed- crop farming systems (GOM 2003; GOM 2006).

As part of the process of implementing the MGDS, the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation is implementing a 5- year (2010–2015), UAC 17 million Agriculture Development Program. The project includes sugarcane development under outgrower arrangements, development of small-scale irrigation schemes, creation of market linkages, and capacity-building for formers, with a target to include 30% female farmers (GOM 2006).

The GOM’s vision for the land sector as outlined in the 2002 Land Policy includes clarification and strengthening of customary land rights and formalization of the role of traditional authorities in the administration of customary land. Despite the creation of the Malawi Land Reform Programme Implementation Strategy (2003–2007), in the absence of an implementing land law, adoption of the principles in the Land Policy has been limited to a handful of donor-sponsored projects (GOM 2008; GOM 2002; Adams 2004; Holden et al. 2006).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

USAID has raised its budget for programs supporting Malawi’s agriculture sector to US $22.5 million in FY10. Programs will be designed to improve food security and implement appropriate market-friendly agricultural policies. USAID will address market- and trade-capacity-related barriers in the agriculturally linked sectors, assist in improving the economic status of and enabling environment for micro-, small and medium enterprises. USAID plans to work with Malawian and international private companies, along with local and international NGOs, foundations, farmer organizations, and agricultural research and trade organizations to increase agricultural productivity and production through the use of improved management practices and technologies (USDOS 2009).

The Community-Based Rural Land Development Project is a land-purchase scheme that was launched in 2005 and targeted 15,000 landless and land-poor households in six districts. The project is administered by the Ministry of Lands with a US $27 million grant from the World Bank. In 2009, the project was extended to 2011 with an additional US $10 million. The project is designed to follow a community-driven development approach that includes: voluntary acquisition of lands by communities; on-farm development, including the purchase of necessary advisory services and basic inputs; and land administration, including regularization, titling, and registration of property rights in land. Beneficiary households organized themselves into groups of 25–30 households and identified underutilized land for purchase. The project provided each household with a grant of US $1050 to be used for land purchase and the initial investment and start-up costs. The early reported experiences identified issues with water provision, and challenges for resettled residents due to the location of the land relative to schools, clinics, and employment opportunities. As of June 2009, the project had resettled 12,656 households on 27,998 hectares, and 1344 households were ready for relocation on 3255 hectares. Each beneficiary household was allocated an average of 2.2 hectares (compared to their original holdings averaging 0.45 hectares). Eighty-nine percent of beneficiaries had received title in June 2009. Yields of maize improved from 962 kilograms per hectare at baseline to 2269 kilograms per hectare through a combination of improved access to land and input support provided by the project’s farm development grant. Tobacco yield has improved from about 519 kilograms per hectare at baseline to 1390 kilograms per hectare. As a result of larger holdings and improved productivity, food insecurity among project beneficiaries has been reduced, and annual household incomes in Malawian Kwacha (MK) have improved from an average of MK 11,830 to MK 32,858 per household (Holden et al. 2006; World Bank 2009b).

The objective of the additional financing for the Community-Based Rural Land Development Project and extension of an additional two years (to 2011) is to help the government increase the agricultural productivity and incomes of the beneficiaries, strengthen the capacity of land administration institutions, and provide further support to reform of the legal framework for land administration. The project plans to use the funding for capacity-building to develop land registries at the district level as well as surveying and registration services. The extension of the project also includes time devoted to assisting the government with the enactment of a new land law (World Bank 2009b).

As part of its pro-poor and pro-growth strategy, the UK Department for International Development (DFID) provided assistance on development of the 2002 National Land Policy. Civil society groups in Malawi formed the Civil Society Task Force on Land and Natural Resources to advocate for pro-poor land rights, in close consultation with grassroots organizations. In cooperation with the International Land Coalition (ILC), LandNet Malawi is preparing a mission to support the Government and stakeholders in the review of land policy and legislation (ILC 2008; UN-DESA 2008; Adams 2004).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Malawi’s water resources cover 21% of its territory and include Lake Malawi (the third-largest freshwater lake in Africa), Lake Chilwa (saline lake), Lake Molmbe, Lake Chiuta, and numerous rivers, wetlands, and marshes. Lake Malawi, which Malawi shares with Mozambique, is the single most important water resource. The country has two main drainage systems (the Zambezi River basin and the Lake Chilwa basin) and two main aquifers (FAO 2006).

The Shire River is the only outlet of Lake Malawi and is responsible for most of the existing hydropower- generation capacity in Malawi. The river travels about 450 kilometers from Lake Malawi to drain into the Zambezi River in Mozambique. The upper Shire River links Lake Malawi and Lake Molmbe; the Lower Shire Valley is one of Africa’s largest floodplains, covering 820 square kilometers during peak flooding and containing the Elephant and Ndindi marshes, which are major wetlands and fishing grounds (FAO 2006; Donda and Njaya 2007).

Distribution of water resources is highly variable based on season and geography; nearly 90% of the runoff occurs between December and June. There are nine major dams on several rivers that supply municipal water systems and are used for hydropower and flood control. The country has about 750 small and medium dams, most of which are in disrepair (FAO 2006; GOM 2004a).

Almost all irrigation is from surface water. As of 2002, about 56,000 hectares of land was irrigated, with about 48,000 of those hectares belonging to estates growing commercial crops such as sugar cane, tea, and coffee. The government has supported several irrigation schemes for smallholders to cultivate rice; as of 2000, there were 40 irrigation schemes operating. The estimated potential for irrigation in Malawi is about 200,000 hectares for formal irrigation and 100,000 hectares for small-scale irrigation. The Lower Shire River Valley is considered to have the greatest potential for development of irrigated agriculture (FAO 2006; GOM 2004a; GOM 2004b).

Malawi has 16 billion cubic meters of annual renewable water resources. Major water users include the agricultural sector, domestic sector, industry, navigation, recreation and tourism, and fisheries. Eighty percent of water is used by agriculture. Domestic water uses include human needs (drinking, bathing, cooking) and income-producing activities such as brick making, livestock watering, beer making, and gardening (World Bank 2009ba; Manda 2009; USAID n.d.; FAO 2006; Mulwafu 2003).

Only three cities in Malawi have central sewage systems, and the discharge of untreated sewage and industrial waste causes water pollution. Water resources in the areas of irrigation projects often carry malaria, cholera, bilharzias, and other waterborne diseases. Irrigation schemes include water supply and sanitation components such as sinking boreholes and providing sanitation facilities to prevent the spread of disease. Independent studies report that 65% of the population has access to safe water (Ferguson and Mulwafu 2004; FAO 2006; Mulwafu 2003)

Despite its significant water resources, Malawi is considered a “water stressed country” by the FAO. Due to the high level of population growth, increasing demands on its water resources, and lack of infrastructure, the country has less than 1700 cubic meters of freshwater per capita and is withdrawing more water than estimates of its renewable water supply. Future projections of water demand predict that Malawi will have less than 1000 cubic meters of freshwater per capita by 2025, which will classify it as a “water scarce” country by the FAO. Experts believe the estimate reflects problems with lack of infrastructure and distribution as opposed to actual water scarcity (Ferguson and Mulwafu 2004; USAID n.d.; World Bank 2009a; GOM 2004a).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1969 Water Resources Act regulates water resource use and conservation and is administered by the Water Resources Board. The Water Resources Act provides for the control, conservation, allocation and use of water. The 1995 Water Works Act provides the legal framework for implementing the water resources management policy and strategies for supplying water and waterborne sanitation services. Local water boards are constituted and operate under the terms of the Water Works Act (Ferguson and Mulwafu 2004; Mulwafu et al. 2003).

A new water act drafted in 1999 addressed gaps in the1969 Water Resources Act through provisions governing water rights, water harvesting, stakeholder participation, and setting a schedule of offences and penalties. The draft law was not enacted. In 2005, the GOM adopted a new Water Policy as part of its first National Water Development Project. The Policy promotes an integrated approach to water resources management and identifies as the primary objective ensuring the sustainability of the resource and service delivery. The government’s second National Water Development Project (2007–2012) includes a component focused on creating a revised water law (Ferguson and Mulwafu 2004; World Bank 2007b; USAID n.d.).

Malawi’s 2000 National Irrigation Policy and Development Strategy calls for the transfer of smallholder irrigation schemes that had been operated by the government to newly formed farmers’ associations, water-user groups, or other local institutional structures. The Irrigation Act of 2001 implemented the strategy, providing for the formation of water-user associations and irrigation-management authorities to promote proper use as well as community and farmers’ participation in developing and managing irrigation and drainage (GOM 2008; Mulwafu et al. 2003; Ferguson and Mulwafu 2004).

TENURE ISSUES

Under the 1969 Water Resources Act and 1995 Water Works Act, Malawi’s water resources are vested in the state on behalf of the population and the public good. Water is free in rural areas, and low-income urban dwellers pay a small fee. Under customary law, all people have rights to water resources, subject to the needs of others. An individual who takes control of water and invests in developing the resource, such as by digging a well, is generally entitled to private use of the resource to the exclusion of others (Mulwafu et al. 2003; Mulwafu and Khaila 2000).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Lead agencies for water resources management are the Ministry of Irrigation and Water Development (MIWD) and five parastatal water boards. MIWD has overall responsibility for the sector, national policy development, and water resources management. MIWD’s mission is to manage and develop water resources for sustainable, effective, and efficient provision of potable water, sanitation, and irrigation systems in support of Malawi’s economic growth and development agenda. The Department of Irrigation facilitates the development of irrigation projects. Agricultural Development Divisions provide local supervision of irrigation schemes (GOM 2008; FAO 2006).

The water boards supply water to cities and towns at commercial rates. A National Water Resources Board advises the government on all matters regarding use, and oversees the processing of applications for water rights and withdrawals. The Board also approves applications for the construction of dams (GOM 2008; Mulwafu et al. 2003; USAID n.d.).

Village headmen and traditional authorities continue to have control over land access in desirable wetland and irrigated areas. In some areas, traditional authorities have allocated wetlands and irrigated lands to newcomers or those with commercial interests, causing disputes with local community members (Kambewa 2005; Holden et al. 2006).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The government’s adoption of the 2005 Water Policy and 2002 National Irrigation Policy and Development Strategy were reforming efforts designed to broaden access to water resources and transfer governance of water resources to local community-based institutions. Following the adoption of the new land, irrigation, and water policies, the government began preliminary steps toward transferring government-operated smallholder irrigation schemes to farmers’ associations. The planned transfers reflect the government’s redefinition of its governance structures and efforts to broaden local access to water resources. Development and adoption of a new water law is anticipated as part of the second National Water Development Project (2007–2012) (Ferguson and Mulwafu 2004; World Bank 2007b).

A major factor affecting productivity in the smallholder sector in Malawi is the dependence on rainfed agriculture. Almost all irrigated land is controlled by estates. Smallholdings relying on rain are vulnerable to adverse weather conditions such as droughts and floods. The Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation is implementing the 5-year (2010–2015), UAC 17 million Agriculture Development Program that is designed in part to help address the need for development of irrigation on small plots. The project includes development of an irrigation system and development of a distribution and drainage network, including canals and lifting plants. The project will also construct two pumping stations for lifting plants (AfDB 2009).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The World Bank supported the US $82 million National Water Development Project (1996–2003) intended to facilitate implementation of the Government’s Water Resources Management Policy by reforming and upgrading the management of water resources and the provision of water-related services. The project assisted the government in developing the national water policy, helped reorganize the Lilongwe and Blantyre Water Boards, and created new water boards. The project provided an estimated 1.5 million people with new or substantially improved water service. The Second National Water Development Project (2007–2012), which is funded by the World Bank, the European Union (EU), the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Netherlands, and numerous other entities at an estimated US $173 million, is addressing water supply and sanitation, the rehabilitation of several cities and towns, water resources management, and urban water sector reform. A significant component of the project will assist in drafting legislation implementing the water policy (World Bank 2004; World Bank 2007b; USAID n.d.).

The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) will co-finance the Irrigation, Rural Livelihoods and Agricultural Development Project initiated by the World Bank. The project builds on the IFAD-funded Smallholder Flood Plains Development Programme, which tapped the potential for small-scale, supplementary irrigation development in flood plains areas, improved rice cultivation in wetland gardening and flood plains, and expanded small- and medium-scale irrigation from surface water and groundwater. The seven-year project supports irrigation development and rehabilitation of existing irrigation schemes. The project emphasizes operation, management and eventual ownership of irrigation schemes by local farmers, who are grouped into water-users’ associations. Other concerted efforts in the water sector include those of the United Nations through UNICEF and nongovernmental organizations including WaterAid (Ferguson and Mulwafu 2004; IFAD 2009).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Thirty-six percent of Malawi’s total land area is classified as forest land. The main types of forests are woodlands, closed evergreen montane forests, stream-bank forests, and montane grassland and semi-evergreen forests. The country has 650 species of birds, large populations of elephant, hippos, zebra, and crocodiles, and has reintroduced lions and black rhinos. The country has 11 protected tree species, most of which are found in the protected areas. Wildlife is rarely found outside protected areas, which are scattered throughout the country. The largest parks are the Nyika National Park (3200 square kilometerss) in the north, and Kasungu National Park (2100 square kilometers) in the central region, bordering Zambia (Halle and Burgess 2006; Bandyopadhyay et al. 2006; Gowela and Masamba 2002; MTMC 2010).

Malawi’s forests provide crucial natural resources for Malawi’s people. Ninety-seven percent of rural households rely on forests and woodlands for fuelwood, which is the primary energy source for cooking. Local populations also use forest resources for food, traditional medicines, cultivation, and income-producing activities such as charcoal production and brick making (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2006; Walker and Peters 2001; GOM 2001; Gowela and Masamba 2002; Mwase et al. 2006).

The national rate of deforestation has slowed in recent years, but almost 1% of forest land is still lost annually. The devastation is particularly marked in the densely populated southern region of the country where 50% of the country’s people reside and only 20% the country’s forest land remains. Biological diversity is threatened by habitat encroachment and decline, overharvesting, and the introduction of alien species (Gowela and Masamba 2002; Walker and Peters 2001; Halle and Burgess 2006).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The primary goal of the 1996 National Forest Policy is to sustain the contributions of forestry resources to uplift quality of life by conserving resources for the benefit of the nation. The 1997 Forestry Act grants authority to the Department of Forestry to control, protect and manage forest reserves and protected forest areas. The Act recognizes the need to promote community-based conservation and management of forests, including provisions for comanagement (Gowela and Masamba 2002; GOM 2008).

GOM is a signatory to many international agreements and conventions protecting forests, including the Protocol on Forestry, which recognizes a commitment to sustainable use and management of forestry resources by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) (GOM 1997; SADC 2002).

The 2005 Standards and Guidelines for Participatory Forestry in Malawi provide the basis for all community-level forestry interventions, including tree planting and comanagement of state forest reserves/plantations. The Standards and Guidelines set out each step of the community-based forest management process. Local forest- dependent communities register as local forest organizations, develop forest management plans, and enter into management and benefit-sharing agreements with the government (FGLG 2008).

Despite the formal legislation and guidelines governing forest land rights, for communities in many areas of the country, customary law and traditional practices govern forest access and use of forest products. Customary law is often highly localized, but some general principles apply, such as the understanding that forests are controlled by chiefs and village headmen, but their resources can be exploited by the entire community. Local communities use forests for hunting, grazing, settlement areas, cultivation, and graveyards. Traditional leaders are charged with the responsibility of ensuring that forest resources are exploited in a manner that serves the interests of the community (Mwase et al. 2006).

TENURE ISSUES

Between 51% and 65% of Malawi’s forests are on customary land; 21% to 22% are on state land (protected areas and agricultural schemes); and the balance is on private freehold and leasehold estates (GOM 2001; Mwase et al. 2006).

The Forestry Act governs the management and use (licensing) of forests on public, private and customary land. On public land, forests are managed as forest reserves and protected forest areas. On private land, tree planting and growing is promoted, and removal of forests is by state permit only. On customary forest land, management is decentralized to Village Natural Resource Management Committees (VNRMCs) that take lead responsibility for licensing activities within a demarcated “Village Forest Area” covered by a management agreement (GOM 1997).

Customary law and traditional practice continue to govern rights of access and forest products in many areas. At least one study found that although for purposes of cultivation Malawians recognize the boundaries of estate land they have for generations used estate lands as a source for wood. They tend to not recognize boundaries as extinguishing their right of access to gather fuelwood in forest and woodland areas. Tree theft from public and private lands accelerated dramatically following the end of the autocratic Banda regime in 1994 (Walker and Peters 2001; Mwase 2006).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The government has a decentralized system of forestry management. At the national level, the Department of Forestry (within the Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Environmental Affairs) is charged with planning, regulating, managing reserves, conservation, and facilitating transfer of forest land to the private sector through leases. The District Forestry Offices take lead responsibility for dissemination of forest resource information to the public, comanagement of forestry resources, fire prevention, and for customary land not covered by a management agreement. The Department of National Parks and Wildlife is responsible for management of the country’s wildlife resources and parks. VNRMCs take lead responsibility for licensing activities within a Village Forest Area covered by a management agreement. To date, few Village Forest Areas have been created (GOM 2001; Gowela and Masamba 2002; Place and Otsuka 2000).

Under the Standards and Guidelines for Participatory Forest Management, communities establish VNRMCs and Block Management Groups (BMGs). Representatives of the block-level group are included in multi-stakeholder Local Forest Management Boards, which govern activities across the whole forest reserve. The District Forest Office assists the VNRMCs with the development of forest managements plans (FGLG 2008).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

In its 2002 National Land Policy, the GOM recognized the dependence of the population on fuelwood, and the need to exploit other energy sources to preserve the country’s forests and woodlands. The policy calls for the development of more extensive forestation programs, encouragement of local community management of forests, development of programs to involve communities in safeguarding forest reserves, conservation areas, and national parks, including benefit-sharing plans. The policy also calls for the preparation of environmental impact assessments before undertaking development in fragile ecosystems like wetlands, game reserves, forest reserves and critical habitats (GOM 2002).

The National Forestry Programme (NFP) is a strategy to link policy and on-the-ground practice for the management and use of forest resources, and, ultimately, improved livelihoods and the alleviation of poverty. The NFP operationalizes the National Forestry Policy and the Forestry Act. A 2003 supplement emphasizes community-based management of forests (GOM 2001; FGLG 2008).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID supported Community Partnerships for Sustainable Resource Management (COMPASS), a five-year (1999–2004) program of community-based natural resources management. The project addressed the rapid rate of deforestation, predominantly in indigenous forest woodland, through public awareness campaigns, capacity- building, and small grants to NGOs. From a climate-change perspective, USAID has worked with the GOM to strengthen the institutional framework for community-based management of forest resources as well as local capacity to manage forests in a more sustainable way. This effort included assisting the Department of Forestry in streamlining its methodology for establishing community management of forest land (USAID 2008a; USAID 2006).

The USAID-funded follow-on project, COMPASS II (2004–2009), was designed to enhance household revenue from participation in community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) initiatives that generate income as well as contribute to safeguarding Malawi’s natural resources. COMPASS II’s objectives were to: (1) increase the decentralization of natural resource management; (2) enhance rural communities’ capacity to sustainably manage their natural resources; and (3) increase sales of natural resource-based products by rural households. At the end of 2007, the project reported seven districts adopting devolution plans for community-based forest management, 1600 communities engaging in community-based natural resources management, 82,000 households participating in project activities, and more than 7000 people trained in CBNRM techniques (USAID 2008b).

The AfDB and the GOM funded the Lilongwe Forestry Project (1995–2004), a rural community-based reforestation project. The project’s objectives were to support the Government of Malawi’s efforts in minimizing environmental degradation, strengthen the Forestry Department’s capacity, and provide fuelwood to ease rural and urban energy needs. The project included community forestry development, forest protection and management, infrastructure development and project management, and institution-building. The main activities were the establishment of nurseries, woodlots and agroforestry farms, the provision of boreholes for water supply, inventories, and infrastructure development. The project produced and distributed over 22 million seedlings against a target of 20 million, established 2080 hectares of poles and fuelwood plantations against a target of 2246 hectares, and provided new sources of clean drinking water. The project was rated as satisfactory, providing support for policy development, development of benefit-sharing forest-management plans, and improving soil fertility through agroforestry techniques (AfDB 2004).

The European Union has invested EUR €15 million to support comanagement of forest reserves through the Improved Forest Management for Sustainable Livelihoods Program, which is being implemented by Cardno Emerging Markets (UK). The project reports establishing 73 village forest area management plans for the management of forests on customary land, the introduction of licenses for the sale of forest produce, including charcoal, fuelwood, and timber that have been granted to VNRMCs, and the first project-related harvesting of firewood from customary land. The project also established 11 local forest management boards, strengthened 227 local forest governance institutions with constitutions and a set of agreed management rules, and led the development and publication of standards and guidelines for participatory forestry management. In April 2010, the European Community (EC) threatened to withdraw EUR €9,800,000 for a second phase due to a lack of government interest in rolling out the project (Halle and Burgess 2006; Langa 2010).

Despite some project successes, community-based forest management has been slow to take hold in Malawi. Implementation of the approach set out in the legislative framework and the 2005 Standards and Guidelines for Participatory Forestry has beyond specific project areas suffered from: lack of understanding of the principles of community forest management among communities and forest department officials; a lack of financial resources; and weak technical capacity. Some researchers have also noted that forest management plans may diverge too much from local traditions and customary practices to have the necessary community support (Gowela and Masamba 2002; FGLG 2008).

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Malawi has been a globally insignificant producer or consumer of minerals, with the sector providing a modest 1% of GDP. The major minerals currently produced in Malawi include coal, gemstones, uranium, dolomite, cement, lime and stone aggregate. The country also has deposits of vermiculite, graphite, iron sulphide, and bauxite that are in various stages of exploitation. In 2009 Malawi’s first significant mine, Paladin’s Keyelekera uranium mine in northern Malawi, began production. As of 2002, approximately 40,000 Malawians, 10% of whom are women, were engaged in artisanal mining (Yager 2007; Torres 1995; Alim 2008; Hentschel et al. 2002; GOM n.d.).

The Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Environment (MNREE) has reported the existence of a variety of unexplored and unexploited mineral resources in Malawi, including significant reserves of coal. According to available estimates, Malawi has identified close to 14 coalfields in the northern region and two in the southern part of the country with speculated reserves of as much as 800 million metric tons of coal. Some of the reserves, such as the Lengwe and Mwabvi coal fields, have been explored; the majority of the reserves are the subject of exploration initiatives that include core drilling operations. The main consumers of Malawi’s coal are cement manufacturing and textile and soap-making enterprises. However, coal could support the tea and tobacco industries and provide energy in the domestic sector through the use of coal briquettes (Alim 2008; Chimwala 2004; GOM n.d.).

The World Bank’s 2009 Mineral Sector Review reported a potential output from Malawi’s mineral sector of US $250 billion annually, assuming planned investments and infrastructure development. The GOM identified the sector as a priority in its 2006–2011 Growth and Development Strategy (World Bank 2010; GOM 2006).

Quarrying and mining operations can result in soil erosion in riverbanks and valleys, create breeding grounds for mosquitoes, and pollute water resources. The proposal by the Australian company, Paladin Energy, Ltd., to mine uranium at Kayelekera (west of Karonga in northern Malawi) ran into significant criticism from local NGOs and civil society members, who concluded that the company’s environmental impact assessment and environmental plan for the project were inadequate to protect the environment and local population from anticipated negative impacts of the mining operation. Following court action and the company’s attention to anticipated environmental impacts, the project proceeded. In late 2009, the mine was near its target production of 200,000 pounds per month (Paladin 2010; Mudd and Smith 2006).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Exploration and exploitation of the mineral resources in Malawi is governed by the 1981 Mines and Minerals Act, the 1981 Mines and Minerals Regulations, and the 1983 Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Act (Torres 1995; Alim 2008).

The GOM has completed a new draft policy governing the mining sector, and presented a new mining law to industry members and NGOs for discussion in April 2010. The MNREE and Ministry of Finance are working with the World Bank on a strategy for finalizing the new legal framework and developing and implementing a comprehensive strategy for developing the sector (World Bank 2010).

Malawi is a signatory to the Protocol on Mining under the SADC. The purpose of the Protocol is to harmonize national and regional policies and strategies related to the development and exploitation of mineral resources. The Protocol is potentially a powerful instrument for effective management of mineral resources for economic development and poverty reduction (SADC 1997; PWYP 2009).

TENURE ISSUES

All mineral rights are vested in the President on behalf of the people of Malawi (Torres 1995).

Under the current law, mineral licenses may be awarded under three categories: (1) a Reconnaissance License (RL) is issued for one year for an agreed program over an area not exceeding 100,000 square kilometers; (2) an Exclusive Prospecting License (EPL) confers exclusive rights to carry out prospecting operations for specified minerals over a specified area; and (3) a Mining License (ML) may be issued to holders of an EPL or non-holders. The ML grants the exclusive right to prospect, mine, produce and sell specific mineral resources from the designated area (Alim 2008).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and the Environment (MNREE) is responsible for the mining sector and is authorized to negotiate incentives and benefits with investors. The GOM encourages local investment in its mineral resource base through joint ventures or local subsidiaries. The Mining Investment and Development Corporation is the governmental holding company responsible for overseeing the mining sector (Torres 1995).

The Government has created a Mineral Licensing Committee, which includes professionals in mining, geology, environmental issues, physical planning, police and customs departments. The committee is responsible for reviewing applications for mineral rights and mining concessions and recommending to the mining minister for for approval (Alim 2008).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The GOM’s Growth and Development Strategy identifies mining as a sector with growth potential that has been constrained by: lack of current information on mineral resources; poorly coordinated institutions; high initial investment costs; inadequate incentives for private sector to engage in medium-scale mining; lack of skills among small-scale miners; and electricity disruptions that threaten production and miner safety. In order to address these barriers and increase the productivity of the sector, the government plans to: (1) develop a functioning institutional setting to promote mining; (2) ensure compliance by small-, medium- and large-scale miners with environmental and safety standards; (3) develop linkages between small-scale miners and legitimate markets for gemstones and other minerals; and (4) increase investment by private sector companies in medium- and large- scale mining (GOM 2006).

The 2002 Land Policy identifies the significant environmental consequences of unregulated mining operations, and calls for enforcement of requirements for environmental impact assessments, conservation method (including the establishment of funds to compensate those adversely affected by mining activities), and requirements that mining and quarrying operators pay the cost of reclaiming land (GOM 2002).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The World Bank’s US $12.5 million Mining Growth and Governance Support Project is expected to begin in 2011 and will include participation from the EU, DFID, France, and the engagement of local and international NGOs. The project will provide technical assistance to the GOM in: finalizing and implementing a new mining policy and law; developing regulations to give effect to the new mining law; conducting a Strategic Environmental and Social Sector Assessment to identify and design appropriate environmental, social and resettlement policies and measures for mining and associated infrastructure-development (including regional and community development planning and agreements); and develop a framework for public-private partnerships. The project will also support development of the GOM’s policy framework for mineral revenue-generation and management, and provide training and equipment to the Ministry to develop a modern mining cadastre system, conduct field work, review and monitor contractual obligations, develop a social and environmental data registry, and acquire geological data. The project includes programs for the development of civil society organizations and local communities’ capacity to engage in environmental and social management and stakeholder dialogue on mining sector development issues (World Bank 2010).