Published / Updated: June 2018

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

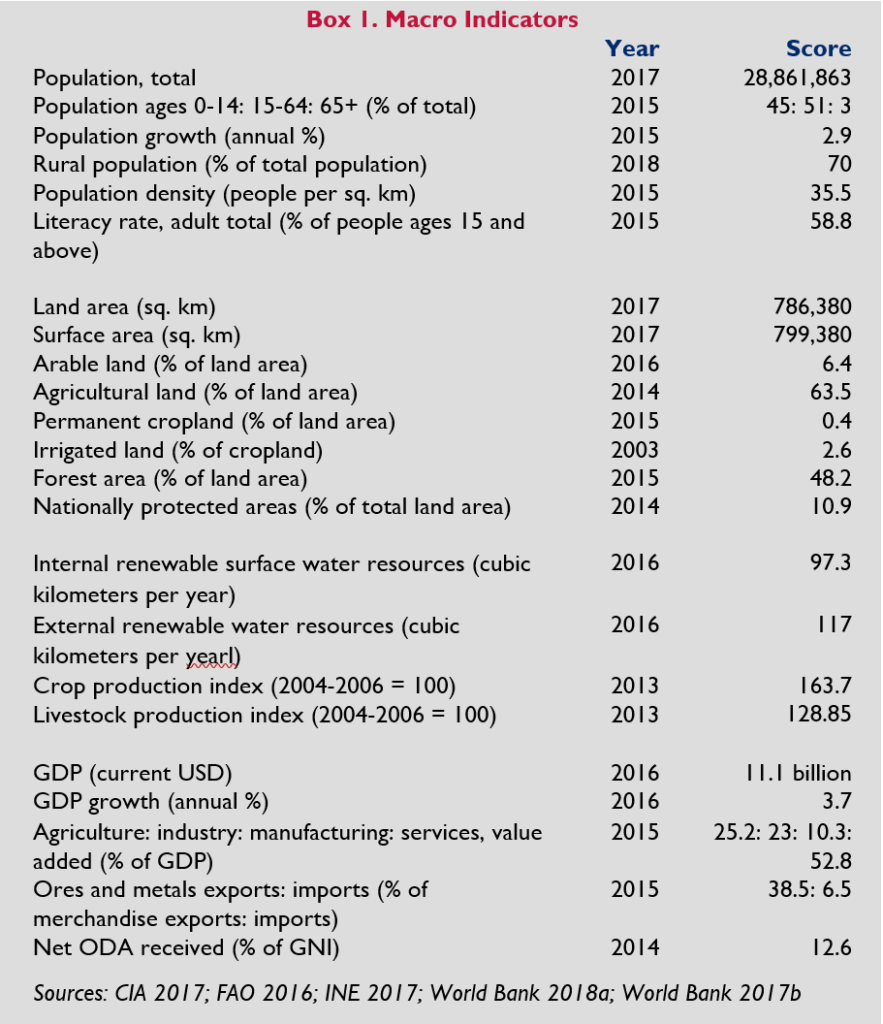

Mozambique is a large, sparsely populated country in southern Africa with a coastline nearly as long as the eastern seaboard of the United States. Following a 16-year civil war that began shortly after independence from Portugal in 1975, ending in 1992, Mozambique achieved political and economic stability and began to experience rapid growth from its small economic base. One important indicator of the country’s potential was the fact that in the first year of peace, with mostly small family farms, agricultural production grew by some 19 percent.

With substantial assistance from international donors, Mozambique began rebuilding its war-damaged and neglected infrastructure, investing in health and education and laying the political and institutional foundation for continued economic growth. An important part of this foundation includes laws governing land and forest use that recognize customary rights held by communities and their members, while also encouraging investment.

Yet despite rapid post-war growth, more than half the population remains poor. Absolute poverty declined to its current level in the early 2000s but has remained stagnant since then, while inequality has increased dramatically. The high growth rates achieved in the early 2000s have also stagnated since 2015 as the country has been hit by a major economic crisis linked to falling world commodity prices, currency devaluation, and a government debt scandal involving sovereign-backed commercial loans worth around $2 billion USD—pushing the Government of Mozambique’s debt burden into the unsustainable category (Kroll 2017). The crisis has drastically reduced state capacity to invest in and run the economy and social sectors and has exacerbated political instability and absolute poverty.

Political stability and democracy established since 1992 have also gone into reverse, with a low intensity armed conflict starting up again after the 2014 elections. Smallholders were displaced in affected areas, although a fragile ceasefire has held for the past year. The ruling party (the Mozambique Liberation Front) and opposition party (the Mozambican National Resistance) are actively negotiating a solution to achieve lasting peace.

Agriculture accounts for around 25 percent of Mozambique’s GDP (2016 estimate), while extractive industry and manufacturing contribute the most to economic growth (CIA 2017; World Bank 2018a). The agricultural sector still consists primarily of smallholders farming limited amounts of land under rain-fed cultivation. Most irrigated land is used by a small number of commercial farmers on large tracts of land, including former colonial farms. The number of medium-sized farms has grown, though they struggle with high transaction costs and difficult access to markets. Recent years have seen a number of large-scale land allocations that have raised concerns about local land rights and the rule of law. While in legal theory land rights are relatively secure for communities and smallholders, the reality is that rights remain vulnerable and are easily captured by powerful elites close to the governing core of the country. This has resulted in increasing instances of conflict between smallholders and government or private sector agriculture, logging, and mining enterprises.

About a half of the land area in Mozambique is forest area, and the country’s legal framework supports traditional uses of forest and forest resources, the harvesting of timber and non-timber forest products, and the creation of community-based forest enterprises. However, the regulatory framework tends to favor national and international companies over small and medium businesses. Poor rural populations have strong incentives to work with illegal operators who are looking to extract high value lumber at minimum cost, resulting in a rate of deforestation that has reached alarming levels in many areas.

Mozambique has significant deposits of gas, titanium, aluminum, coal and diamonds. The civil war prevented the development of the minerals sector, but this has changed since 2000. Historically, most mining has been done by small-scale and artisanal miners, who continue to operate without effective environmental and health safeguards. Several very large investments in coal and natural gas have transformed the sector, along with 2014 revisions to the Mining Law intended to protect small operators while also creating the conditions for large-scale enterprises. A notable feature of the legislation is that it effectively overrules local land rights through what is essentially a ‘national interest’ approach. The government has invested in major public infrastructure to facilitate the growth of the mining sector, although the economic crisis has impacted plans to consolidate this investment. It remains unclear what impact this growth may have on artisanal and small-scale operators, who receive little government support. New foreign investments in titanium and offshore oil and gas are moving forward.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

A newly elected government in 2014 created the Ministry of Land, Environment and Rural Development (MITADER). This important move replaced the Ministry for Coordination of Environmental Affairs (MICOA) and integrated land and rural development, previously managed under the agriculture and state administration ministries. MITADER has separate national directorates for the environment, land, and forests and promises better coordination between these closely related areas with a single, unified development strategy and a renewed focus on improving law enforcement. MITADER is also embarking on a significant update of the progressive 1990s legislation governing forests, land, conservation and the environment. Progress has, however, been hampered by the country’s weak economic state and institutional base inherited from past governments. Plantation forestry remains at the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (MASA), creating a new institutional and coordination challenge. A proposal to combine all land-related institutions- such as the land and real estate cadastre, territorial organization, and land use planning- is being promoted by some government officials and civil society. Donors may want to support the establishment of a unified Land Administration Agency and help support development of strategies to promote the financial sustainability of the land sector to the wider economy.

Mozambique’s 1997 Land Law reasserts the state’s ownership of land and provides that individuals, communities and entities can obtain long-term or perpetual rights to land, even without formal documentation of those rights. This right is known by the acronym DUAT, from the Portuguese Direito de Uso e Aproveitamento dos Terras. While in theory, the law provides communities and individuals with strong tenure security over their land, the majority of Mozambique’s millions of rural residents lack the capacity to secure their rights in practice- despite significant civil society and government efforts to raise awareness of rights at local level. Those who are aware of their rights often lack the financial and technical support necessary to assert and use those rights effectively. Furthermore, the dual objectives of Mozambique’s progressive Land Law – to protect and support rural community and smallholder land-rights while encouraging an inclusive and rights-aware private investment process – have been implemented unevenly. Local land rights remain vulnerable to capture by elites who often enjoy state support on the grounds that they have greater capacity than smallholders to bring unused resources into production. These conditions make it difficult for communities and individual landholders lacking formal land documentation to defend their land rights against third parties, make long-term investments in their land, or meaningfully engage in negotiations with the private sector. While some reform can address ambiguities in the Law, far more attention is needed to increase the government’s implementation capacity and enable an integrated approach that develops and provides accessible services for communities and allows them to fully realize the potential of their land. Several large donor-backed projects have targeted the land-rights issue, including the Millennium Challenge Corporation’s (MCC) Land Tenure Services Project and the DFID-led multi-donor Community Land Initiative. The Land Tenure Services Project supported policy and legislative review through a new Land Policy Consultative Forum established by Government of Mozambique (GOM) decree in October 2010. The project also supported practical Land Law implementation with public outreach and dispute resolution, community rights registration, and the regularization and titling of individual DUATs. That said, more support could help the Government strengthen the land governance system. Donors could help develop a services center model, or upgrade and consolidate district-level capacity, to deliver land and natural resource services to communities and their members. Donors could help private and civil society actors build awareness of the various legal instruments that individuals and communities can use (such as natural resource inventories, land delimitation services, and legal aid) to secure rights. Donors could support the government to train public officials and local community leaders in facilitating more inclusive development opportunities that promote and mediate community-investor partnerships that involve access to and use of local land. Specific attention should be paid to developing and offering services to meet the needs of women, elders and marginalized groups.

Until the MCC Land Tenure Services Project, most donors engaged in land issues in Mozambique supported public awareness building and delimitation of community-held DUATs acquired by customary occupation. Less attention has been paid to small and medium-size individual-held DUATs, whether the land user seeks individualized rights to land within a collective DUAT held by a community, or seeks access to agricultural land through a government-granted DUAT. Both customarily-acquired and government-granted DUATs are equivalent under the law, and their delimitation and registration creates a public record of community-held and managed areas, and of individual land parcels. Between 2012-2016, individual land use registration increased ten-fold, with the number of formal DUATs rising from approximately 45,000 in 2011 to 150,000 in 2013, 270,000 in 2015, and 490,000 in 2016. This was achieved with important contributions from MCC’s Land Tenure Services Project as well as other initiatives promoted not only by the government, but by civil society organizations, other donors and private companies. In April 2015, the GOM launched a large-scale program – Terra Segura – to secure land rights and issue DUATs to five million individuals and four thousand communities by 2019. Donors could help support and extend Terra Segura or provide complementary activities with a particular focus on: supporting district-level land use planning which integrates community DUAT registration and land management functions into the public land governance structures; improving the land information infrastructure; and activities that focus on the rights of women farmers and smallholder enterprises.

Mozambique has a system of about 1,600 community courts that evolved separately from the formal court system. The community courts are highly accessible, and community members often bring land disputes to these forums even though the adjudicators do not receive professional training and the procedures and outcomes lack consistency. Donors who have been assisting the government in strengthening its formal court system and improving judicial administration could help support and deepen on-going efforts to develop effective mechanisms and forums to resolve land disputes. Donors could assess the community court system and options for strengthening the informal system and linking it to the formal system. Particular attention should be paid to community court functions related to land disputes, including the interface between customary and normative legal systems, the use of formal documentation and records, the use of community courts by non-community members, and the relationship of community court officials to their government counterparts. Donors could also support and fund community-level legal services, through training of and support to community paralegals, who can assist in directing claims to higher level courts when necessary.

In 2010, the GOM created a Consultative Forum on Land to serve as a platform for multisector dialogue on land issues and to assist in the legislative reform process. Nine sessions were held between 2010 and 2017. There is broad consensus among Forum participants that the essentials of the 1997 Land Law should not be changed. However, at the November 2017 Forum meeting, members agreed to prioritize the massive titling of DUATS and recommended that the GOM develop and improve the institutional framework governing land, and look to revise the Land Law to allow for transferability of DUATs (MITADER 2017). A 2007 study commissioned by USAID identifies several areas for potential legislative reforms, including removing constraints on transfer of rural land rights, developing appropriate authorization fees and taxes for land grants, allowing investors to recover and profit from real property improvements at the end of approved use periods, and moving the government away from its present direct-management role towards a facilitating and enabling role in land management and administration. A key issue is to limit government discretionary powers when reviewing existing and new project proposals and when DUATs are transferred between third parties. The Forum offers a good platform for achieving these reforms. Progress has been made by adopting rules for resettlement processes and creating supporting regulations and in measures to combine land administration and land use management. Members of civil society are calling for the development of legislation on community land governance functions, community consultations with investors and other land management tasks. These changes would help communities and the private sector, which is increasingly interested in working with out-growers and neighboring communities in a responsible and secure local environment. Donors can continue to provide technical assistance and support to the government as it engages in the process of collecting input on legislative reforms in the land sector, including proposed language and revisions.

Mozambique has significant forest resources and a substantial number of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) operating in the forestry sector. Yet weak governance – characterized by low institutional capacity and a lack of transparency, limited participation of stakeholders in decision making, and inadequate benefit sharing with local communities – has fueled deforestation and forest degradation (Aquino et al. 2017). An estimated 76 percent of all global timber exports from Mozambique in 2013 were illegally cut in excess of reported harvests (EIA 2013). Most commercial operators work outside the formal law to avoid concession requirements, and establish relationships with poor rural residents to illegally extract unprocessed timber directly for export. In late 2017 a new Forest Law was drafted to replace the 1999 Forest and Wildlife Law that remains in force (wildlife and conservation issues were addressed and updated in the 2014 Conservation Law). USAID and other donors could assist the government with reforming and unifying the current legal framework (as proposed in the draft law) and assist with plans to encourage SMEs to move into the formal sector. This revised legal framework should seek to ensure that appropriate safeguards are in place to support the sustainable use of forest resources by all forest users. It should also ensure the participation of all community members – especially women and marginalized groups – in forest enterprises and ensure that some returns generated by commercially-oriented forestry activities, including new carbon sequestration projects, flow to communities.

Summary

Mozambique’s independence from Portugal in 1975 was followed by 16 years of civil war. The war displaced millions of people, destroyed infrastructure and prevented significant investment in several sectors, including agriculture and mining. As the country emerged from the war and entered a period of national reconstruction, the government turned its attention to creating a legal framework governing land that recognized customarily-acquired and managed community rights while also encouraging investment. The resulting 1997 Land Law was progressive: land is owned by the state which then allocates a legal right to all land users, known by the acronym DUAT. Local people and communities acquire DUATs through customary and ‘good faith’ occupation. These DUATs are perpetual over land used for subsistence and household economy purposes. Grants of 50-year renewable DUATs are available at little cost for investors and others seeking land for agribusiness and other development, subject to approved development plans and environmental licensing. Investors are legally required to consult with communities and agree on terms of how a DUAT will transfer from one group (the community) to the other (the investor). However, the implementation of the law has been hampered by a chronically weak public land management and land administration sector, and by well-connected elites. Corruption contributes to poor law enforcement. Legal reforms are needed, but structural issues also need to be addressed, otherwise ineffective implementation is likely to continue.

Mozambique’s independence from Portugal in 1975 was followed by 16 years of civil war. The war displaced millions of people, destroyed infrastructure and prevented significant investment in several sectors, including agriculture and mining. As the country emerged from the war and entered a period of national reconstruction, the government turned its attention to creating a legal framework governing land that recognized customarily-acquired and managed community rights while also encouraging investment. The resulting 1997 Land Law was progressive: land is owned by the state which then allocates a legal right to all land users, known by the acronym DUAT. Local people and communities acquire DUATs through customary and ‘good faith’ occupation. These DUATs are perpetual over land used for subsistence and household economy purposes. Grants of 50-year renewable DUATs are available at little cost for investors and others seeking land for agribusiness and other development, subject to approved development plans and environmental licensing. Investors are legally required to consult with communities and agree on terms of how a DUAT will transfer from one group (the community) to the other (the investor). However, the implementation of the law has been hampered by a chronically weak public land management and land administration sector, and by well-connected elites. Corruption contributes to poor law enforcement. Legal reforms are needed, but structural issues also need to be addressed, otherwise ineffective implementation is likely to continue.

To date, most of the population has not benefited sufficiently from the legal reforms of the 1990s and early 2000s, with more than half of the population remaining absolutely poor. Most agricultural producers are small farmers growing primarily for their own consumption. On average, farmers hold between one and two hectares of land and use limited inputs. They also rely on access to communal land and forest resources to meet their vital needs. Their long-term strategy often requires access to (and therefore secure rights over) much wider areas to facilitate long-cycle crop rotation and shifting agriculture. Productivity is low and technology is rudimentary, primarily due to limited access to credit and extension services. Most irrigated land is used by a small number of large commercial farmers, primarily growing sugarcane and other crops such as cotton and tobacco. The law requires government approval of projects to use land, and approval of any transactions that involve a change in land-use rights. This cumbersome process constrains the development of an open and transparent formal land market. Former colonial farms and large tracts of long-term land use rights acquired for investment are often only partially used. In many cases, private investors who acquired rights at favorable terms hold large parcels for future use or speculation. The government’s failure to require investors to prepare commercially viable development plans and demonstrate their ability to use the land, coupled with lax enforcement of the Land Law audit provisions, have contributed to the underutilization of land. This is exacerbated by a land tax system which does little to promote the most efficient use of land resources. Negative results include small family farms that are denied the use of land that was once theirs, while potentially more efficient medium-sized (10-100 hectare) farmers find it hard to secure the land they need.

While the 1997 Land Law provides communities and their members with a legally secure land use right, the law has been inadequately implemented in most areas. Local officials and communities are often unaware of the law governing the land rights of communities and individuals. Registration of customary and good faith occupancy rights is voluntary, and few communities or individuals have the financial and technical support necessary to delimit their land and register their rights to obtain a formal DUAT. As a result, third parties are either unaware of or ignore existing local rights. In many cases, the required consultation between investors and communities is complied with only in form, not in substance. Communities are often inexperienced in negotiation skills, and lack adequate legal support in consultations with investors.

In cities, the majority of residents live in informal settlements with limited public services. The Land Law provides a basis for long-term residents to formalize their rights, but most are unaware of the process and those who are aware consider the costs prohibitive. Meanwhile, there is an active informal (illegal) market in land use rights in both urban and rural areas. Although a DUAT cannot legally be sold, land users can sell improvements on the land as private property. This provides a loophole for a de facto land market through the sale of very basic improvements for large amounts of money. The government does not recognize these transactions, yet also fails to prohibit them. As a result, it forgoes the opportunity to raise revenue from fees or taxes on these transactions and on the long-term use of land for private use. These revenues could contribute to the sustainability of land administration services, and support public investment in other key areas such as social services, basic water, sanitation and roads.

Mozambique has yet to take advantage of its abundant surface and groundwater resources. Civil war, neglect, and lack of technical capacity have led to the destruction and decay of water distribution and irrigation infrastructure. Overall access to a safe water supply is low at 49 percent of the population, with a large disparity between urban coverage (80 percent) and rural coverage (35 percent) (UNICEF 2014). The country has significant potential for irrigation—estimated around 3.1 million ha—yet only 118,000 ha were actually irrigated in 2012 (FAO 2016). The country’s vast territorial marine waters have also been underutilized. At the same time, there are numerous accounts of illegal fishing in territorial waters.

Nearly half of land in Mozambique is forest land, and the legal framework governing the sector is reasonably progressive. Local communities have rights to use the forest and forest resources for traditional purposes, and they can obtain licenses to harvest timber and non-timber forest products. The legislation supports community forest management and some projects (with significant and on-going NGO and donor support) have created successful community-based forest enterprises. However, the regulatory framework generally works against small and medium businesses and, as a result, most operate in the informal sector. This means that the most valuable forest concessions are held by national and international companies. Illegal logging is rampant in the country as operators work through poor local residents to extract unprocessed timber for export. Measures have been taken to ban the export of unprocessed timber logs and a moratorium was established for timber exploitation through licenses which lack appropriate environmental and other requirements. In 2016, a process to review the forestry and wildlife legislation was initiated by MITADER and a new law has been drafted.

Mozambique’s minerals sector suffered from lack of investment throughout the country’s civil war and has only recently begun to develop. The country has significant deposits of several minerals, including titanium, aluminum, coal and diamonds. The government is concentrating on the development of infrastructure, such as railways, port expansion and creation of electronic data sources to support the industry.

Land

LAND USE

Mozambique has a total land area of 786,380 square kilometers, comprising three geographic areas: (1) a plateau and highland region running from the northern border to the Zambezi River (27 percent of total land); (2) a middle plateau region that extends south of the Zambezi River to the Save River (29 percent); and (3) a low-lying coastal belt running south from the Save River to the southern border (44 percent). The northern and central areas of the country have tropical and subtropical climates; the south is dry semi-arid steppe and arid desert climate. The dominant vegetation is woodland, and about a quarter of the country’s woodlands and forests are generally free from cultivation. Average annual deforestation is 0.35 percent, representing an annual loss of nearly 140,000 hectares (World Bank 2017a; FAO 2005; ARD 2002). Terrestrial protected areas comprised 21.6 percent of Mozambique’s land area in 2016 (World Bank 2018a).

Mozambique’s coastline is 2,515 kilometers long, and a wide range of marine products are available and marketed. The domestic market is mainly confined to the marine and coastal areas, although aquaculture production is increasing. Fishing contributes to approximately three percent of GDP and about 850,000 families depend on fishing for part of their income (UNCTAD 2017).

The country’s population is estimated at 28.9 million (INE 2017), approximately 70 percent of whom live and work in rural areas. During the 16 years of civil war that followed the country’s independence from Portugal in 1975, much of the rural population migrated to urban centers and across international borders to escape violence. Following the declaration of peace in 1992, many returned to their rural homes, relying on subsistence farming, forest products and the development of cash-cropping to support their livelihoods (Hatton et al. 2001; ARD 2002; FAO 2005). Population displacement continues, though at a lesser scale, as a result of low intensity warfare that started in 2014.

Agricultural land makes up 63.5 percent of Mozambique’s total land area, and agriculture remains the main economic activity for most of the rural population. An estimated 90 percent of producers are smallholders cultivating rain-fed land. Most smallholder production is concentrated on staple food crop production (maize, pigeon peas, cassava and rice) for household consumption. The balance of production is cash crops (such as cotton, tobacco, oil seeds and tea) and vegetables. Tree crops, especially coconut and cashews, are grown by smallholder farmers and are a significant source of income in coastal areas of the central provinces of Nampula, Zambézia, and in the Inhambane and Gaza provinces north of Maputo. Much of the country’s soil is nutrient-poor. Most smallholders have limited inputs, and yields are generally low. Smallholders also raise cattle, pigs, chickens and goats, although cattle production is limited by the prevalence of the tsetse fly in two-thirds of the country (ARD 2002; World Bank 2009a; FAO 2005; USDOS 2010; FAO/WFP 2010; FAO 2013).

The remaining 10 percent of producers are commercial farmers producing crops for the national market and export. Major agricultural exports are cotton, cashew nuts, sugarcane, tea and cassava. Large commercial operations cultivate an estimated 100,000 hectares, including about 40,000 hectares on industrial sugarcane plantations (35,000 hectares under irrigation) near sugar mills in the southern part of Maputo and the Sofala provinces (ARD 2002; USDOS 2010; FAO/WFP 2010).

Approximately 32.8 percent of Mozambique’s population lived in urban areas in 2016, with annual urban population growth estimated at 3.8 percent. Around 75 percent of urban residents live in unplanned informal settlements, many without access to safe water and sanitation. Most urban residents are engaged in subsistence agriculture at the outskirts of cities or in the informal labor market. About half the urban population lives on less than $1.25 a day (UN-Habitat 2009; UN-Habitat 2008; World Bank 2017b; Negrão 2004).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Mozambique has an ethnically diverse population, with about 70 percent of the population belonging to one of three ethnicities. The Makhuwa (or Makua-Lomwe, 37 percent of total population) live primarily in the regions north of the Zambezi River. The Tsonga (23 percent) tend to live in the regions south of the Zambezi River, while the Shona (9 percent) live mostly in the central regions. Smaller groups include the Makonde, who live primarily along the Rovuma River on the northern border with Tanzania, and the Yao (or Ajawa), who live in the northwest Niassa Province. Other groups include the Nguni, Maravi and Chopi. Europeans, Indians and Euro-Africans comprise less than 1 percent of the population (USDOS 2010; Joshua Project 2010). Land ownership does not appear to disproportionately favor particular ethnic groups.

Landholdings in Mozambique tend to be either smallholdings or very large concessions on the scale of hundreds or thousands of hectares. The average farm size in Mozambique ranges between one and two hectares, and approximately three-quarters of all agricultural holdings are less than two hectares (INE 2011). Smallholders depend upon access and user rights to extensive communal grazing and forest resources, and to arable land to support long-cycle crop rotation and shifting agriculture. There are relatively few medium-sized (10–100 hectare) landholdings.

At independence in 1975, the vast majority of Portuguese colonists left the country, and the state nationalized large colonial farms and attempted to organize peasant producers into agricultural collectives (cooperatives). Most farms failed to meet expectations for productivity. To promote agricultural production, the government offered the state farms and other large tracts of land at little or no cost to investors who had the capital and experience to operate commercial enterprises. From the late 1980s through the early 1990s, the state awarded an estimated 2.8 million hectares in concessions. Concessions were generally awarded with little regard for customary rights or the land use practices of local communities. In some cases, entire villages were included within concessions granted to third parties (Tanner 2002; Norfolk and Tanner 2007; NAI 2007).

At independence in 1975, the vast majority of Portuguese colonists left the country, and the state nationalized large colonial farms and attempted to organize peasant producers into agricultural collectives (cooperatives). Most farms failed to meet expectations for productivity. To promote agricultural production, the government offered the state farms and other large tracts of land at little or no cost to investors who had the capital and experience to operate commercial enterprises. From the late 1980s through the early 1990s, the state awarded an estimated 2.8 million hectares in concessions. Concessions were generally awarded with little regard for customary rights or the land use practices of local communities. In some cases, entire villages were included within concessions granted to third parties (Tanner 2002; Norfolk and Tanner 2007; NAI 2007).

Following the end of the civil war in 1992, demand for land grew on the coast and in areas with fertile soil, access to markets and good roads. State concessions were again readily available and investors were not required to demonstrate their financial ability to develop the land. Often, they paid only administrative fees for rights to use the land. Reliable comprehensive information regarding large land concessions is limited, but records from the period 2001 to 2003 indicate that the government received 5,500 applications for land, covering 3.9 million hectares. It is impossible to say to what extent concessions encompass land held by local communities. However, in line with underlying precepts of the Land Law, and its recognition of customary and good faith occupancy rights even without formal documentation, it is likely that most concessions are over land that was, or is still legally occupied by local communities (NAI 2007; Tanner 2002; Norfolk and Tanner 2007).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 2004 Constitution of Mozambique provides that the ownership of all lands and natural resources vests in the state, and that all Mozambicans shall have the right to use and enjoy land as a means for the creation of wealth and social wellbeing (Article 109). The Constitution further provides that the state shall recognize and protect land rights acquired through inheritance or by occupation, unless there is a legal reservation or the land has been lawfully granted to another person or entity. The Constitution also recognizes state, municipal and community public domain over land and natural resources. Despite government guidance to do so, the legal regime for community public domain has yet to be developed or approved (GOM Constitution 2004).

The 1997 Land Law was drafted with the objective of supporting and protecting the land rights of communities, women and smallholder farmers while also encouraging investment—reasserts the state’s ownership of land and provides that individuals, communities and entities can obtain long-term or perpetual rights to land. This right is known by the acronym, DUAT from the Portuguese Direito de Uso e Aproveitamento dos Terras, or the ‘the right of land use and benefit of land’. A DUAT protects the customary rights of communities to their traditional territories and recognizes the land rights of communities and individuals acquired through customary systems and good faith occupancy, even without formal documentation of those rights. Community land use rights are legally equivalent to rights granted by the government to individuals and entities. A Technical Annex to the Land Law includes a process for identifying and recording the rights of local communities and good-faith occupants (Norfolk and Tanner 2007). Article 24 of the Land Law, and constitutional provisions regarding community public domain, give the ‘Local Community’ clear and devolved land and natural resources administration functions within their delimited areas of jurisdiction. The Land Law further provides women and men in Mozambique with equal legal rights to hold land. Nationals have unrestricted rights to access land, while foreign individuals and entities must have local residence and an approved investment plan. Land use is free for family uses, local communities, the state, and smallholder associations and cooperatives (GOM Land Law 1997; Norfolk and Tanner 2007).

The 1998 Rural Land Law provides rules for the acquisition and transfer of use-rights. These rules provide for private property developed on the land to be marketable (i.e., ‘improvement’ or ‘benfeitorias’), with the transfer of the underlying DUAT then subject to a discretionary approval process by the state. This mechanism facilitates and supports the current informal land market, where basic assets are sold for large sums. Ironically, it also frustrates the emergence of a formal land market that would allow individuals, groups and some business entities to access credit for investment purposes, as the discretionary power of the state introduces an element of uncertainty, making investments riskier (GOM Rural Land Law 1998).

Decree No. 1/2003 establishes new provisions for the National Land Registry and Real Estate Cadastre, and procedures for the registration of inherited land use rights and secure rights to customary rights-of-way (GOM Decree No.1/2003).

The 2006 Urban Land Regulations apply to existing areas of towns and villages and to areas subject to an urbanization plan. The Regulations governs the preparation of land use plans, access to urban land, rights and obligations of owners of buildings and DUAT holders, and transfer and registration of rights (GOM Urban Land Regulations 2006).

TENURE TYPES

Two main categories of land are prevalent in Mozambique:

- Public lands (state and municipalities): The Constitution determines which lands are held under state public domain, and over which no DUATs can be issued. Parties interested in occupying public land may apply for a special license.

- Community lands: Most rural land is held by communities, who have perpetual DUATs based on their traditional occupancy. Delimitation and registration of this land is voluntary as communities are not required to delimit or register their land to assert their DUAT (LANDac 2016).

The DUAT is the only recognized holding and use right over land, and it can be held individually or collectively. According to the Land Law, a DUAT can be acquired in three ways:

- Customary occupation following customary norms and practices (this applies to local communities and individuals and households within them);

- Good faith occupation (after using the land for at least 10 years uncontested); or

- Adjudication and allocation of a 50-year lease by the State.

Occupancy-based DUATs can be registered with the National Directorate for Lands (DINAT) of MITADER to give notice and formal documentation of rights, but do not need to be registered for the holder to assert and defend the use-rights to occupied land (Norfolk and Tanner 2007; GOM Land Law 1997; GOM Land Regulations 1998). DUATs obtained by customary and good faith occupation are perpetual and do not require plans for exploitation (use) of the land. However, if communities want to formally register their DUAT, they must prepare an exploitation plan. Members of local communities can obtain DUATs for individual plots within the community land, but have to go through a process of consultation with their local leaders.

The large areas of land that fall within the remit of local community DUATs, but which are not covered by individual customarily acquired DUATs are classified as community public domain. This means that the respective local community has land and natural resource management powers devolved to it by the State. Other areas of public domain land include: the large totally and partially protected areas, such as National Parks and official hunting reserves; public utility land including airports and roads; and all land required for public service infrastructure and government. Most of the latter areas fall within the public domain of municipalities, while parks and reserves fall under state public domain and are now managed by the National Conservation Agency. According to the Constitution, DUATs cannot be allocated in public domain spaces, raising questions over how DUATs are in fact allocated in areas of community public domain. The amount of land comprising partially protected areas (buffer zones of roads, rivers, railways, airports and defense facilities, power lines, etc.) is unknown, and the same applies to areas of community public domain.

In terms of acquiring a DUAT from the State, there are no minimum or maximum sizes of land, though grant applicants must prepare an exploitation/land use plan. For areas over 10,000 hectares, this plan must include the terms of any partnership agreement negotiated with the existing DUAT holders (local communities and/or individuals). If the application for a DUAT is accepted, the land must be surveyed, and boundaries determined, and the DUAT issued must be registered in the cadastral register maintained by DINAT. The state issues a provisional grant for either two years (to foreign persons or entities) or five years (to nationals). If the exploitation/land use plan is fulfilled, the grant becomes final. If the plan is not fulfilled, the land reverts to the state, unless the investor provides a justification. If land rights are revoked due to lack of fulfilment of the exploitation/land use plan, the state receives rights to any improvements made to the land and the grantee has no right to compensation (GOM Land Law 1997). Registration of a DUAT obtained by grant creates a presumption of legitimacy of rights and is presumed to prevail over a conflicting unregistered DUAT.

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

In urban areas, most residents (approximately 62 percent) access land through the informal land market, either by leasing land held by DUAT holders or, more commonly, through buying the ‘improvements’ on the land (resulting in an informal land market). Leasing and buying land are both technically illegal under the current constitutional framework and formal law. However, any ‘improvement’ made on the land, as opposed to the land itself, is considered private property, and can be bought, sold or mortgaged. (NAI 2007; Norfolk and Tanner 2007). Other means of accessing urban land include customary rights systems such as inheritance or borrowing (19 percent), state allocation (13 percent) and good-faith occupation (6 percent).

In rural areas, most land is held by communities and individuals with unregistered DUATs acquired through customary and good faith occupation.

As of 2016, only an estimated 951 of 5000 rural communities in Mozambique had delimited their lands; an area of approximately 17,256,257 ha. Among these 951 communities, 763 have completed files to register their DUAT while only 387 communities have completed the registration process (DINAT 2017). DUAT registration requires eight procedures, an average of 42 days and a payment of approximately 11 percent of the value of the property registered. The state is required to process applications for DUATs within 90 days, though there are no consequences if the deadline is not met. Costs vary by the extent and location of land, but as of 2003 the average cost of delimitation and registration of community land was estimated at about $8,000. (CTC 2003; Chilundo et al. 2005; Norfolk and Tanner 2007; Tanner 2002). Recent information puts the cost at approximately $4,500 (Topsøe-Jensen et al. 2017). Further, the process requires the applicant to have an identity card, which many residents do not have and can acquire only by navigating additional procedures. The actual registration process is also considered expensive and inconvenient because the registry office is either in Maputo or in provincial capitals (NAI 2007; Norfolk and Tanner 2007; World Bank 2010a). As a result, the vast majority of registered DUATs are held by wealthy and corporate right-holders who understand and can work within the formal legal framework.

A great advance of the 1997 Land Law was the introduction of a legal requirement that all investors seeking land must consult with the relevant local community to see if the land is in fact available; and if it is not, then they must negotiate terms with the existing DUAT holders to gain access (GOM Land Law 1997; Akesson et al. 2009). The consultation process and resulting agreement presents an opportunity to encourage local participation in rural development in partnership with new investors. In practice, investor consultations with communities have tended to be quite limited and have had little positive impact on planning for development. Challenges to local participation include communities’ lack of knowledge regarding their land rights and investor’s obligations, low participation in decision-making among community members, including women and marginalized groups, and lack of capacity among local government officials charged with managing the process. Communities that have had the benefit of NGO support have fared better than most in this process (Tanner and Baleira 2006). Civil society has called for the development of a law on community consultations to improve how the consultations are conducted and help prevent disputes and tension between communities and investors (Cotula et al. 2009; Norfolk and Tanner 2007; Dobrilovic 2011). Pilot projects implemented by NGOs are working to reduce the time and costs of community consultations by giving a more prominent role to community authorities and community members in most phases of the delimitation process (Tankar and Rafael 2015; Terra Firma 2013).

Although unregistered land-use rights obtained by occupancy are widely recognized and viewed as akin to ownership, they remain invisible on official maps, and government officials are generally unaware of the extent of these rights. The increasing demand for land by investors makes such ‘invisible’ rights vulnerable to allocation by the state to third parties. The question of land occupation is therefore controversial: communities and NGOs supporting community rights contend that little if any land is unoccupied in Mozambique, while government has reported that as many as seven million hectares are available because they are vacant or under-used (Norfolk and Tanner 2007; Kanji et al. 2005; Adams and Palmer 2007; AfDB 2008). As such, many investments in Mozambique are controversial and subject to protests by affected communities and NGOs, mainly for failing to conduct proper consultations and failing to fulfill promises made to communities. Lack of rigor in law enforcement regarding community consultation, combined with a lack of adoption of guiding instruments such as land use plans and Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), are apparent in investments involving economic and/or physical resettlement. In most cases, consultations are carried out in a cursory manner. The result is that the Land Law is used to give an impression of legitimacy to the granting of land over areas where local rights exist and that are important for local livelihoods (Tanner 2010).

Some of the most controversial investments include projects in the biofuels sector (ProCana Biofuels), mining (Vale Mozambique Mineral Coal; Kenmare Heavy Sands), hydrocarbons (Anadarko Gas) and commercial agriculture (ProSavana and Wanbao). In 2009, the government cancelled a DUAT that had been provisionally granted to ProCana for the development of 30,000 hectares for biofuel production in Massingir District, Gaza Province. Only 800 hectares had been developed at the time that the DUAT was cancelled. The project resulted in communities losing grazing land, constrained access to local water sources, and loss of a planned wildlife reserve—issues that resulted in negative media coverage and delayed the land development. The government’s cancellation of the DUAT was, perhaps, less evidence of the government’s systematic analysis of investor compliance with development plans than an indication of poor tenure analysis and lack of planning prior to granting the DUAT in the first place, and the government’s vulnerability to local and international pressure (Weltz 2009; Gunter 2010). Other projects have also been controversial and subject to protests due to poor consultation processes. The government is seen as solely concerned with investor’s interests at the expense of community rights, while investors are seen as taking advantage of government weaknesses and apparent willingness to by-pass procedures that would ensure adequate consideration of community rights and interests and respect to the rule of law.

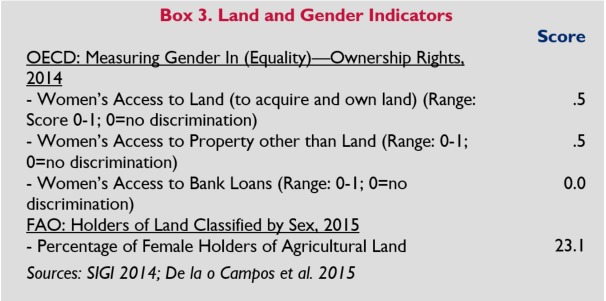

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

In general, Mozambique’s formal law supports and protects women’s rights to land. The 2004 Constitution provides for the equality of men and women in all spheres of political, economic, social and cultural life, and prohibits discrimination based on sex. The 2004 Family Law provides for the equality of women by recognizing that women and men have equal rights to administer marital property and have equal rights to devolve and inherit property. The 1997 Land Law gives women the right to participate in all land-related decisions and the right to register DUATs individually. However, the primary formal law governing inheritance and succession (the 1966 Portuguese Civil Code) favors men over women for inheritance and management of marital property. Formal courts continue to apply the Succession Chapter of the 1966 Portuguese Civil Code.

Despite the progressive framework supporting the equality of women, customary law and traditional practices continue to dictate most women’s social and economic rights in Mozambique, including access to land and access to secure tenure. The formal law allows for joint ownership of marital assets and the right to register land individually, but few women (and especially rural women) have any assets in their names. Women generally obtain access to land through their birth families until they are married, after which time they access land through their husbands. Under customary law, women generally do not inherit land. In patrilineal societies in the southern regions, land passes from fathers to sons and, in the absence of male offspring, to close male relations such as uncles. Even in matrilineal societies found in the northern regions of the country, land passes to male members of the female line (Schroth and Martinez 2009; Hendricks and Meagher 2007; Alfai 2007; van den Bergh-Collier 2003).

Despite the progressive framework supporting the equality of women, customary law and traditional practices continue to dictate most women’s social and economic rights in Mozambique, including access to land and access to secure tenure. The formal law allows for joint ownership of marital assets and the right to register land individually, but few women (and especially rural women) have any assets in their names. Women generally obtain access to land through their birth families until they are married, after which time they access land through their husbands. Under customary law, women generally do not inherit land. In patrilineal societies in the southern regions, land passes from fathers to sons and, in the absence of male offspring, to close male relations such as uncles. Even in matrilineal societies found in the northern regions of the country, land passes to male members of the female line (Schroth and Martinez 2009; Hendricks and Meagher 2007; Alfai 2007; van den Bergh-Collier 2003).

Without assets, and dependent on relationships with men for access to land, women are extremely vulnerable. Widows and divorced women in both patrilineal and matrilineal areas are often at risk of losing their homes and access to agricultural land. In some cases, families will provide land, but the women will be considered socially subordinate and so they are provided with land of poor quality. Village leadership is generally male-dominated and may offer women little support (Schroth and Martinez; Alfai 2007; van den Bergh-Collier 2003).

Other cultural barriers also negatively affect women’s land rights in Mozambique. In general, women have lower literacy and lower levels of formal education than men and are less likely to be aware of their rights. Women are often excluded from, or poorly represented in, local governance bodies and thus have more limited access to information. Women tend to have less experience with administrative procedures and are less likely to invoke the legal system to support their rights. However, when legal assistance and support is provided to women, widows in particular benefit. In a 2006 program operated by the Association of Women Legal Professionals in Nampula, the most common cases brought were widows seeking land and housing taken when their husbands died. In most cases, widows received some benefit as a result of the intervention (Schroth and Martinez 2009; Waterhouse 2001; Alfai 2007; Hendricks and Meagher 2007; FAO 2017).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The former National Directorate of Land and Forests of the Ministry of Agriculture was integrated into the Ministry of Land, Environment and Rural Development (MITADER). Responsibilities for land management and administration within MITADER fall under the National Directorate for Land (DINAT) and the National Directorate for Territorial Planning and Resettlement (DINOTER). At the national level, the DINAT is the regulatory authority, charged with holding and organizing the national land cadastre records (including SiGIT, the digital Land Information Management System) and, in the case of large-scale land applications over 1000 ha, responsible for processing applications for approval. The DINAT also provides technical guidance to the cadastral services of the provincial administrations and the decentralized municipalities. For rural land, the Provincial Service of Geography and Cadastre (SPGC) has primary operational responsibility. The municipality cadastre services issue DUAT documents for occupants of urban areas. DINAT shares responsibilities for land cadastre services with the Housing Registry Services (Conservatoria do Registo Predial), located within the Ministry of Justice (Norfolk and Tanner 2007; CTC 2003; LANDac 2016).

In general, Mozambique’s land administration bodies lack capacity to perform their statutory functions (Burdick 2016; World Bank 2017c). In some cases, land administration personnel have maintained a top-down or investor-focused approach and have failed to accept the participation of local communities in land management and development decision-making (World Bank 2017c). In some areas cadastral authorities at provincial and district levels appear to believe that they are primarily responsible for serving the interests of investors. In other cases—and particularly in local offices—personnel have not received adequate training and support. Most public resources allocated to land administration are devoted to supporting outside investment in urban and rural areas, while relatively few resources are available to help communities delimit land and prepare for consultations with investors (Norfolk and Tanner 2007; CTC 2003; Dobrilovic 2011; CTV 2017).

NGOs and donors have played a significant and ongoing role helping the government implement the 1997 Land Law. With the exception of a small government-sponsored pilot program conducted at the time the Land Law was passed, NGOs and donors are primarily responsible for building community awareness of land rights and helping communities and local governments delimit community land and register community DUATs. A 2016 assessment conducted using the World Bank’s Land Governance Assessment Framework (LGAF) provided specific recommendations for institutional reform to improve performance of the land management and administration sector, with particular attention given to protection of rights, and to effective and sustainable land use.

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Demand for land in Mozambique is increasing, especially in urban and peri-urban areas, rural areas with access to markets and infrastructure, and those areas that might leverage tourism. In urban areas, DUATs can be transferred automatically with the sale of buildings and other improvements. In rural areas, government permission is required to transfer a DUAT. Relatively few people transfer land use rights through formal channels. In urban areas, many parties are unaware of the requirement of registering land rights transactions. The cost of registering transactions is high and the process is cumbersome. In rural areas, the requirement for prior government approval of the transfer invites a highly discretionary government evaluation of land use, which creates a risk that the DUAT will be forfeited. In addition, the Land Law does not specifically provide for partition of land under a DUAT, creating uncertainty as to whether the holder of a DUAT can transfer a portion of a specific land parcel (Norfolk and Tanner 2007; Tanner 2002; World Bank 2010a).

The informal land market is active in urban and peri-urban areas, and several studies suggest that the number of transactions is increasing, especially in areas with basic infrastructure and urban growth. Individuals with formally and informally acquired DUATs are transferring all or some portion of their land use rights through rental agreements, loans and subdivisions. Land speculation is occurring in some areas. Those with financial capacity buy plots by buying whatever infrastructure might be in place on the land (even a rudimentary wall will do). They then secure their rights through construction of a sub-standard house or building and sell the plots for higher prices. There is less evidence of an informal market in agricultural land, but the modest capacity of land administration offices and lack of registered DUATs covering smallholdings suggests that an informal market exists and is growing in the absence of efforts to support the development of a formal market in rural land (Norfolk and Tanner 2007; NAI 2007; World Bank 2017c). Land researchers have called for state intervention on this issue to recognize and regulate the currently illegal land market.

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Article 82 of the Constitution provides that the government can expropriate land only for reasons of public necessity, utility or interest and that the government must pay fair compensation to the landholder(s) (GOM Constitution 2004).

Under the 1997 Land Law, the right to use property may be lost in four circumstances: (1) failure to carry out the investment plan in connection with which the DUAT was issued; (2) revocation for reasons of public interest; (3) expiration of the term of use, if any; and (4) renunciation by the titleholder. Where use-rights have been lost, the rights revert to the state (GoM Land Law 1997, Art. 18). In cases of revocation for reasons of public interest, the government is required to conduct an expropriation process and pay a fair indemnification and/or compensation before land use rights are extinguished. The law does not specify procedures or standards for establishing fair compensation, though the government did approve a decree to regulate compensation in the context of involuntary resettlement. This legal instrument must be combined with the legislation on territorial zoning and planning (Law No. 19/2007 of July 18, and by Decree no. 23/2008 of July 1) as well as the regulation on involuntary resettlement.

Compensation amounts and procedures for land expropriations are often agreed to by the principal stakeholders on a negotiated case-by-case basis. Anecdotal evidence suggests that in some cases displaced people have received land and assets of equal size and value to those taken. There is considerable doubt, however, whether such cases are representative of the norm (Swedish Geological AB 2003). Furthermore, in the case of involuntary resettlements, displaced people should be compensated in a way that puts them in a better position and with better condition than those they had in their places of origin. NGOs and others have claimed that, aside from including compensation for loss of land use rights, compensation packages should also include the value of other intangible assets such as social cohesion and networks, spiritual linkages to the land and ancestors, etc. (CTV 2017; World Bank 2017c).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Land disputes are relatively common in rural areas where concessions have been granted within or near a community’s traditional territory. Because the Land Law does not require communities to register their rights, local governments and investors often fail to recognize the extent of community land and the nature of community land uses, and community consultations are often ineffective. The lack of knowledge of community rights and lack of understanding among parties of procedures necessary to approve investment projects is a leading cause of disputes. Other causes for disputes in rural and urban areas include boundary disputes, inheritance and intra-family rights and land transactions (CTC 2003; Unruh 2001; Hendricks and Meagher 2007; Kanji et al. 2005; Salomão and Zoomers 2013; World Bank 2017c).

Mozambique’s formal court system has jurisdiction over land-related disputes. The country’s system includes an administrative court to hear challenges to state administrative actions, and district courts, provincial courts and a supreme court. At all levels, the formal court system suffers from a lack of skilled administrative personnel, lack of qualified judges, and inadequate facilities and equipment. The litigation process is lengthy (the average contract enforcement action consumes more than 1,000 days), requires parties to be represented by lawyers and includes high fees (10 percent of the estimated value of the claim). The judicial system has historically lacked independence and has been plagued with corruption (World Bank 2017c). Since the early 2000s, more focus has been placed on legal education, and judicial training programs, particularly through the Center for Legal and Judiciary Training, which has helped to strengthen the judiciary at all levels (CTC 2003; AfDB 2008; FAO 2017). Legal training on land and natural resources management has been provided to other government sectors such as district administrators and public attorneys, police commanders, among others (FAO 2017).

The Institute for Legal Assistance and Support (Instituto de Patrocínio e Assistência Jurídica) is a state institution created in 1994 to provide pro bono legal assistance to the poor. The Institute has offices in the provincial and some district capitals but has lacked necessary financial support to ensure adequate staffing and skills (Alfai 2007). With the same purpose, the Lawyers’ Bar Association also established a department for provision of pro bono legal assistance which has also intervened in the mediation of land disputes. Many civil society organizations, such as Centro Terra Viva (CTV), Justiçia Ambiental (JA) and Forum Mulher also provide legal assistance to rural communities on land issues.

The Constitution recognizes legal pluralism whenever fundamental rights are not contradicted, resulting in a legal regime that combines formal and customary law. Most rural lands, representing the majority of the national lands, are managed by customary law and by traditional authorities. Mozambique also has a system of about 1,600 community courts that evolved separately from the formal court system, and these handle civil and criminal matters, including land disputes. Community courts are staffed by elected community members. No training is required, and community courts apply a local and often highly inconsistent blend of formal law, customary law and other informal norms. There is no established link between community courts and the formal judicial system. Parties to disputes are free to initiate an action at the district court without exhausting remedies available in community court (Hendricks and Meagher 2007; Ikdahl et al. 2005, Monteiro et al. 2014).

Most of the population uses informal mediation and conciliation processes to resolve disputes. Elders, traditional leaders, neighborhood heads, district officials and many NGOs provide informal dispute-resolution services. Some bodies, such as district administrators, provide arbitration and adjudication services, and some provinces have special dispute-resolution commissions supported by technical advisors on issues such as delimitation processes. Most disputes are resolved in these forums, particularly in rural areas where access to another forum would require significant travel and expense (Alfai 2007; CTC 2003; Hendricks and Meagher 2007, Monteiro et al. 2014).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

In 2006, a Community Lands Initiative (Iniciativas para Terras Comunitárias, or ITC) was established along with a dedicated land fund. This initiative involved supporting efforts to strengthen the land rights of rural communities and development of the technical capacity at the community level to manage land sustainably. The fund supports community land delimitations and development of community projects. The funded activities are implemented by NGOs, the private sector and government bodies. ITC initially focused on Cabo Delgado, Maniça and Gaza provinces. With MCC funding, the fund was expanded to include Niassa, Nampula and Zambezia provinces. The fund is demand-driven and therefore able to respond to particular needs—a flexibility that, for some land analysts, potentially allowed it to support other identified land-related public needs to the neglect of community land delimitation (De Wit and Norfolk 2010; Nhancale et al. 2009). In October 2016, ITC was institutionalized and transformed into the Community Lands Foundation (ITC-F) and it expanded its geographic focus to the whole country.

In 2010, the GOM created a Consultative Forum on Land to serve as a platform for multi-sector dialogue on land issues and to assist in the legislative reform process. Nine sessions were held between 2010 and 2017. There is broad consensus among Forum participants that the essentials of the 1997 law should not be changed. However, at the November 2017 Forum meeting, members agreed to prioritize the massive titling of DUATs and recommended that the Government develop and improve the institutional framework governing land and look to revise the Land Law to allow for transferability of DUATs (MITADER 2017).

Government support to the agricultural sector focuses on the Strategic Plan for Development of the Agricultural Sector (PEDSA 2011–2020). This initiative aims to increase domestic production of main food staples and integrate the markets of different regions to strengthen agricultural value chains. The strategy is consistent with the more general Action Plans for the Reduction of Poverty (PARP 2010-2015), which prioritize increasing agricultural productivity and integrating the sector into the rest of the economy. The strategy does not directly address agricultural land access or land tenure security (FAO/WFP 2010). Land tenure security in the context of land-based investments, including agriculture investments, has been addressed by the Consultative Forum on Land, which approved specific land governance guidelines in the 2012 Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forest in the Context of National Food Security and the 2012 African Union Land Policy Framework (FAO 2012). In 2014, the Government approved the National Development Strategy (Estratégia Nacional de Desenvolvimento) which highlights the need for sustainable use of renewable and non-renewable natural resources. However, it doesn’t include specific guidelines for the land sector.

In 2015, MITADER launched the Terra Segura program, which has three main objectives: (1) to consolidate the land administration and management system; (2) to protect local community rights while promoting citizenship and sustainable development; and (3) to deliver information about individual and community land rights in general. As part of Terra Segura, the Government has pledged to deliver five million DUATs in the next five years and 4,000 community delimitations. The aim of Terra Segura is to help delimitate and secure the tenure of mostly poor, rural populations by mapping their land and registering their DUATs for free. With the assistance of the development of the Sistema de Gestao e Informacao de Terras (SiGIT) land information management system from MCC, Mozambique has expanded the pace at which it has granted DUATs, successfully granting about 300,000 DUATs since the beginning of the Terra Segura program.

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

USAID was an initial supporter of land initiatives in Mozambique through its support to a program of applied research on land-tenure issues, conducted by the Land Tenure Center at the University of Wisconsin. The research supported by the Land Tenure Center, together with national research commissioned by UNDP, fed into a wider policy review process ahead of developing new land legislation. An FAO project supported the creation of a new Inter-Ministerial Commission for the Revision of Land Legislation. The FAO worked with the government to guide formulation of the 1995 National Land Policy. This Policy formally established the key principles of recognition of customary rights and land management procedures, the underlying tenets of the consultation process and a more inclusive, rights-based development model.

The National Land Policy was then given concrete force by the development of the new Land Law by the Inter-Ministerial Commission, again with FAO and Land Tenure Center support and involving a wide range of national stakeholders. FAO has since been a strong strategic partner supporting the implementation of the law. Working with the Center for Legal and Judicial Training (CFJJ) of the Ministry of Justice, the FAO trained national and local level judges in the new land and natural resources laws that appeared in the latter half of the 1990s. It then went on to work with the CFJJ to develop a paralegal training program in land and other related laws, including environmental and physical planning laws, and investment and tourism legislation. This program grew to incorporate training for local government officials and NGOs on the legislative framework and delimitation process, and the concept of negotiated and inclusive development with land plot delimitation and community consultation at its core. A manual for paralegals and communities was one notable output from this work.

Overall, this program trained 1,200 paralegals who work in provincial associations. In some provinces, such as in Cabo Delgado and Inhambane, district paralegals’ associations are being created with technical support from local NGO Centro Terra Viva (CTV), who took over this component from the CFJJ when FAO funding was terminated (Tanner 2010; Adams and Palmer 2007; CTC 2003; NAI 2005). Finally, from 2010 to 2014, a dedicated women’s rights component was added to the FAO-supported program, training women paralegals and supporting women’s associations in the countryside to defend women’s land rights and secure DUATs for women individually and in associations (Tanner and Bicchieri 2014).

The U.S. Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) managed a $507 million compact with Mozambique’s government. The compact included a $39 million Land Tenure Services Project that worked to: improve the policy framework; upgrade land information systems and services; help communities and individuals register land rights; and improve the accessibility of land for investment. (MCC 2007; MCC 2009; Adams and Palmer 2007). One major achievement was the development and deployment of the Sistema de Gestao e Informacao de Terras (SiGIT) land information management system. This system is currently maintained by the government, but with difficulty, particularly with reference to technical assistance and basic IT infrastructure. However, it does provide a cornerstone for building an improved land governance system in the country.

USAID’s 2014-2019 Country Development Cooperation Strategy (CDCS) for Mozambique prioritizes inclusive economic growth and private sector investment to increase agricultural productivity and expand agribusiness and tourism. The Strategy also aims to increase equitable access to land and tenure security to help create an improved business climate to attract investment and create jobs (USAID/Mozambique 2015). USAID currently supports the Support Program for Economic and Enterprise Development (SPEED+) in Mozambique. SPEED+ is providing expert technical services to the Government of Mozambique to support economic and structural reform in the areas of agriculture, trade, business enabling environment, energy, water and biodiversity conservation. Specifically relating to land administration, the activity is providing support to MITADER to lead an inclusive process to revise a number of land administration regulations and norms, including technical norms for issuing DUATs, how community consultations must be carried out, and when investor’s DUATs will be revoked. The activity is also supporting private sector public debate around more controversial issues of land as an economic asset, transferability of DUATs, and sub-leasing. The 2017 USAID Responsible Land-Based Investment Project supported Africa’s largest sugar producing company (Illovo Sugar Africa Ltd.) to secure land use rights for individuals and farmer association members in the area surrounding its Maragra Estate.

The U.S. Government’s Feed the Future FY 2011-2015 Multi-Year Strategy for Mozambique identified the need to support land use planning and management to bolster climate change adaptation and private sector investment. The Strategy also identified the need to support policy initiatives that advocated for freely transferable land titles, available for use as collateral, with particular emphasis on women’s equal rights to land (USG 2011).

The African Development Bank (AfDB) also had a program to assist the governmnt in the development of the judicial and administrative systems relating to land rights, in part to assist the government in resolving land-related disputes and speed up the processing of applications for land use rights. The AfDB has also assisted the government in updating the land registration system, but progress has not been reported (AfDB 2006; AfDB 2008).

The MCC Land Tenure Services Project supported policy and legislative review through a new Land Policy Consultative Forum established by Government of Mozambique (GOM) decree in October 2010. The project also supported practical Land Law implementation with public outreach and dispute resolution, community rights registration, and the regularization and titling of individual DUATs. During project implementation, in the rural areas a majority of DUATs were either issued to women, or women acquired the right together with men.

The Land Tenure Services Project was followed by support to DINAT from the Netherlands, Switzerland and Sweden. The Swiss Development Cooperation has recently approved its new strategy for the period 2018-2022 with continued support reserved to the land sector.

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Mozambique has 104 identified river basins and shares nine major river basins with other countries. The basins mostly carry water from the central African highland plateau to the Indian Ocean. The rivers have a highly seasonal, torrential flow regime with high waters during three to four months and low flows for the remainder of the year. In addition, Mozambique shares two large lakes with neighboring Malawi: Lake Niassa (Lake Malawi) and Lake Chirua (Lake Chilwa) (FAO 2005).

Mozambique has abundant renewable groundwater sources at around 17 cubic kilometers per year. Annual internal renewable surface water resources are estimated at 97.3 cubic kilometers. External renewable water resources are around 117 cubic kilometers per year, primarily from the Zambezi River, which enters Mozambique from the border of Zambia and Zimbabwe. With an installed capacity of 2,060 megawatts, the Cahora Bassa Dam on the Zambezi River in Tete Province is the largest hydroelectric plant in Southern Africa (FAO 2005; FAO 2016).

The country receives an average annual rainfall of 1,032 millimeters, which varies widely across the country and from north to south. The north and central regions receive up to 2,000 millimeters of rainfall per year, the coast receives 800–1,000 millimeters, while the southern inland and border areas receive as little as 500–600 millimeters per year (FAO 2005; NEPAD 2004).

The main source of water in the country is surface water, although people rely on groundwater for drinking water in urban centers and many rural areas. Agriculture accounts for 87 percent of water use, while 11 percent of water withdrawals are for domestic uses and two percent for industry. The country has an estimated irrigation potential of 3.1–3.3 million hectares. The country has significant potential for irrigation—irrigation potential was estimated to be around 3.1 million ha by the FAO- especially in the central provinces, yet in 2012, only 118, 000 ha were actually irrigated (FAO 2016). Most of the irrigation potential is in the northern and central regions (60 percent of the potential is in Zambezi Province). The southern regions have the greatest need for irrigation, but only a small share of suitable land (World Bank 2009b; FAO 2005; FAO/WFP 2010).

Overall access to a safe water supply is low at 49 percent, with a large disparity between urban coverage (80 percent) and rural coverage (35 percent) (UNICEF 2014) Most rural water is provided through piped village systems and boreholes with hand pumps. At any given time, up to 35 percent of the rural systems are not functioning because of poor management, and donor-financed water and sanitation sector interventions often fall quickly into disrepair. An estimated 36 percent of the population obtains water from unprotected wells, and cholera, dysentery and other waterborne diseases are chronic problems (AllAfrica 2010; USAID 2006; Water-Technology 2010). A severe drought affecting most of southern Africa over the last three years has led to a water crisis in the capital city of Maputo and low rainfall has left a dam that supplies the city with most of its water to just 19 percent of capacity. In rural areas, the lack of water has wiped out crops and killed livestock. As a result, the food security and nutritional situation in the country went from 1.5 million food insecure people in March 2016 to 2.1 million in November 2016 (SETSAN 2017).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK