Published / Updated: July 2011

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

Current conditions in Ecuador may present a window of opportunity for progress on land tenure and property rights, for three primary reasons. First, the 2008 Ecuadorian Constitution and progressive legislation such as the new Public Finance and Planning Code, the Decentratization Code, the National Territorial Strategy, and the National Plan for Well Being have increased effective representation of all Ecuadorians and created opportunities for public participation in political processes, including advocating for improved land rights and support for the rule of law. Second, a growing awareness of the importance of environmental issues in Ecuador provides an opportunity to bring tenure issues to the forefront, as they are closely related to conservation of biodiversity and use of natural resources including land, water and forests. Third, USAID program success in the areas of conservation, protection of biodiversity, and land titling and registration may provide a platform for increased activity in all of these areas.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

Decentralization has provided local governments with the opportunity to have a greater voice in land matters, but some local governments lack the capacity to take advantage of the recently devolved authority. Through its Municipal Strengthening Project, USAID is providing technical expertise to promote effective and accountable governance at local levels. The project plans to provide at least 20 local governments with training and technical support for institutional strengthening, income generation, and civil society participation. The Municipal Strengthening Project creates an opportunity for the GOE to strengthen capacity in land administration at the local level. Working with the framework created for the Municipal Strengthening Project and drawing on the experience implementing the USAID Integrated Management of Indigenous Lands Project, USAID and other donors could extend the scope of the assistance provided to local governments to include capacity building and institutional strengthening to support land administration functions through technical training and assistance developing and refining systems and procedures.

Empirical data on land markets in Ecuador is old and much of the secondary research is anecdotal or limited to discussion of general trends. It is important to understand levels of formality and informality in the land markets, and to quantify numbers of titleholders and registered parcels. Also, more is needed to understand the reasons for legal and institutional constraints on land market development. As part of more general support for the decentralization process, USAID and other donors could work with the GOE and local government institutions to undertake a comprehensive assessment of the status of rural and urban land market development and analyze the legal, institutional, political, economic, and cultural reasons for weak land market development.

Registration records are outdated for over half of all rural properties, and an additional 12% of rural properties lack titles. Registering a land transaction takes upward of a year, and the administrative structure for registration and titling can in some cases be duplicative and lack transparency. USAID and other donors could work with the GOE to improve, update, and simplify the land titling and registration systems for both rural and urban land.

Increased numbers of migrants to urban areas and natural population growth in the cities have propelled rising demand for housing in urban areas. At the same time, constraints in the formal market, such as a lack of land suitable for development, have kept prices for housing in the formal sector out of reach for the poor and for many middle-income families as well. Land invasions have ensured and informal settlements are common. Most urban poor have insecure land rights and their living conditions are inadequate. The GOE is implementing a new program through the Ecuador Institute of Social Welfare (IESS) to provide poor families with a subsidy and bank credit for housing purchases. USAID and other donors could help the GOE ensure that the new program provides the intended benefits to poor families by conducting baseline and preliminary research and surveys of vulnerable populations, developing targeted pilot programs, creating procedures and processes for the program that ensure its benefits reach the most marginalized groups, and helping local NGOs identify beneficiaries and support their participation in the program. Donors can also provide the GOE with technical assistance and support for plans to formalize the rights of poor families to plots in informal settlements and help to identify and address barriers preventing poor people from accessing the formal land and housing markets in urban areas in the future.

Although the law provides that women enjoy the same land rights as men, this is not the case in practice. Additional research is needed to determine how to make this legal equality a reality on the ground, especially in regard to land titling and registration. Any future donor initiatives related to land titling, registration, or conflict resolution should incorporate strong gender components specifically aimed at promoting women’s rights to land.

Indigenous territories are critical in Ecuador because they cover a fifth of the country and indigenous peoples are among the most marginalized in Latin America. Many indigenous peoples have a long-term vision that combines biodiversity conservation with sustainable use of renewable resources in a strategy to improve the quality of their lives. USAID and other donors have been active supporters of projects to formalize the rights of indigenous communities and provide them with the technical and institutional resources to manage their land. These efforts — including USAID’s Conservation of Indigenous Territories project, Initiative for Conservation in the Andean Amazon, and Sustainable Coasts and Forests project – will be generating a substantial amount of data and experience that could be useful to the development of expanded and related programs. USAID and other donors can help ensure that project experience is captured and evaluated and lessons learned and best practices collected and disseminated in order to inform the refinement and expansion of current projects and development of follow on projects.

Ecuador‘s ecosystems are under extreme pressure. The country‘s high deforestation rate is a result of oil exploration, logging, road-building, and market demand for agricultural products such as daily, meat, and palm oil. However, the GOE is committed to combating further environmental degradation through the ―Nature‘s Bill of Rights‖ in the 2008 Constitution, and as a member of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO), which has developed criteria and indicators for sustainable forest management and a platform for dialogue between national forestry authorities and through its efforts to achieve REDD+ readiness. (REDD+ is an effort to create a financial value for the carbon stored in forests, offering incentives for developing countries to reduce emissions from forested lands and invest in low-carbon paths to sustainable development.). USAID and other donors could build upon Ecuador’s commitment to combating deforestation by supporting programs that protect existing forests, restore degraded forests, promote sustainable livelihood activities for local communities outside of forest areas, and encourage dialogue among all stakeholders currently using forest resources.

Summary

Ecuador is a small and densely populated country and has the 11th highest rate of biodiversity in the world. Land distribution within the country is highly unequal along geographic and class lines; a result of this is that the rural poor tend to work in agriculture, have limited or no access to land, and work low-productivity land.

Rapid urbanization and increased informality have put pressure on Ecuador‘s cities to provide land, housing, and infrastructure. The current status of land ownership, which is fragmented, is a function of changing patterns of land tenure and land ownership in the urban periphery driven, in part, by land reform policies.

Land

LAND USE

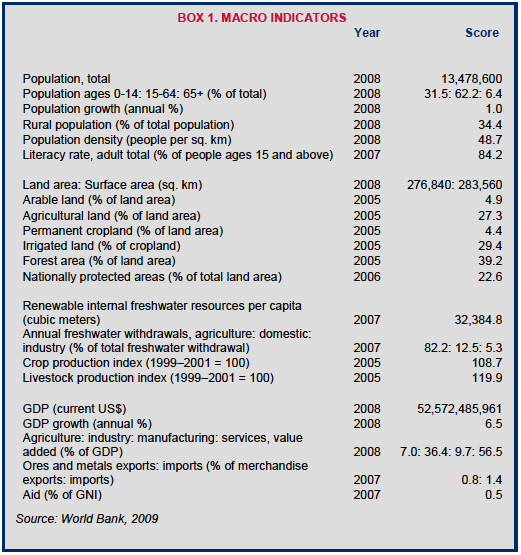

Ecuador is one of the smallest countries in South America with a total land area of 256,370 square kilometers. The country‘s land area was reduced by 20,430 square kilometers (from 276,800 sq. km) as a result of a border agreement with Peru in 1998. The country is composed of: tropical rainforest, including cloud forest above 2,000 meters; a dry deciduous forest along the southern coast; savanna in the south; desert in the extreme southwest; and dry forest, grass, and steppe in the Andean region. Of total land area, 27% is agricultural land, 39% is forested, and 23% is protected. Of total cropland, 29% is irrigated (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) 2002; World Bank 2009; European Commission (EC) 2007; World Bank 2011; USDOS 2010; USIP 1998).

Ecuador is also the most densely populated country in South America. As of 2008, the total population was 13,479,000, and preliminary results of the 2010 census show the population has grown to 14.3 million. Thirty-four percent of the population is rural and approximately 38% live below the national poverty line (2006 data) (Aguilar and Vlosky 2005; World Bank 2009; Geohive 2011).

Ecuador‘s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is composed of 7% agriculture, livestock, and forestry, 36% industry and 57% services. Though only contributing 7% of GDP, agriculture employs roughly 30% of the labor force. The rural population is dependent on agriculture; however, according to the World Bank the sector suffers from problems including low productivity, limited diversification, high vulnerability to natural disasters, insufficient quality control, and irregular

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE, AND DISTRIBUTION

Ecuador has ample water resources. The country has four times more water per person than the global average; however, water resources are dependent on forests. Some areas have experienced prolonged drought and/or extreme flooding, which may be linked to increased deforestation. Inappropriate and inequitable water distribution exacerbates an overall reduction of water reserves. Water availability is also negatively affected by erosion of river banks, population growth and increasing urbanization, growth in agricultural production and a corresponding need for irrigation, and poor water systems planning (FAO 2006; Ramazotti 2008; IDB 2008).

While increasing numbers of Ecuadorians have access to clean water and sanitation, recent estimates indicate that more than half of all families lack access to water and adequate sanitation (IDB 2008).

Government capacity to manage public water resources is weak. There are no plans to establish any sort of water quality control system (Ramazotti 2008).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE, AND DISTRIBUTION

Ecuador has a very rich forest resource base. The country has 11,679,822 hectares of forest, which is comprised of six types: Wet Tropical Forests (rainforests); Dry Tropical Forests; Mangrove Swamp Forest; Flood Plain Forest; Mountain Forests; and Wet and Dry Temperate Forests. These forest types are located in the various regions of the country. There are more than 1,856 total known animal species in Ecuador, giving Ecuador the 11th highest rate of biodiversity in the world. Public forestland is comprised of the National System of Protected Areas (SNAP), which covers around 18% (4.7 million hectares) of inland territory with 34 protected areas; as well as the Protected Public Forests, which cover around 9% of inland territory; and the State Forest Estate (PFE) which covers approximately 8% of the inland territory (Forest Dialog Secretariat 2010).

Forests are used for firewood, bamboo, tagua nuts, and the harvest of plywood, balsawood, and ‗raw wood‘ (eucalyptus and teak). Of all wood harvested in the country, 67% is used either as fuel wood, illegally logged or wasted. Between 17.5% and 54% of timber is harvested and traded illegally. As a result, Ecuador‘s rate of deforestation – 1.5% annually – is four times higher than that of other countries in the region. Dry forests are vanishing at a rate of 2.2% per annum. Loss of forestland threatens many endemic plant and animal species (Aguilar and Vlosky 2005; FAO 2006; World Bank 2009).

Indigenous communities and the state are the primary forest owners in Ecuador, although many private individuals also claim forestland rights, and land

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE, AND DISTRIBUTION

Gold, silver, lead, zinc, copper, iron, coal, and salt are mined in Ecuador. Overall, investment in mining is modest by Andean standards. In 2006, the total value of production by the mineral industry of Ecuador was almost entirely (98.67%) accounted for by the value of production of crude petroleum. Other minerals produced in small quantities include limestone for cement and glass manufacture, and other industrial minerals, such as feldspar, pozzolan, pumice, kaolin, and barite (Anderson 2009).

In Ecuador, national policy overwhelmingly supports petroleum extraction. Oil is Ecuador‘s largest grossing national product, and national interest in ensuring its development is critical in light of the country‘s considerable foreign debt (USDOS 2006; USDOS 2009).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Under Ecuadorian law, minerals are the property of the state. Any zone may be reserved by the state for its exploitation or exploration. Certain areas, including hydrocarbons, radioactive substances, and mineral water are regulated by special laws beyond those generally applicable to mining. Environmental regulations for mining activities are established by Decree No. 625 of 1997 (Martindale Hubbell 2008).