Published / Updated: October 2016

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

Peru’s almost 31 million inhabitants benefit from the country’s exceptional biodiversity and abundance of natural resources. However, these are threatened by land degradation, deforestation, water pollution and weaknesses in the management of Peru’s forests, minerals and water. Furthermore, although Peru’s formal laws recognize the autonomy and rights of the country’s indigenous and peasant communities, there are still land titling and disputes issues, and these groups have the highest rates of poverty in the country. In recent years, programs to develop cadastres and provide titles for rural and urban land resulted in roughly half the land being titled; this includes formalization of informal rights in urban and peri-urban areas. However, while women have received an increasing share of rights to agricultural land, they often participate very little in community governance decisions about land and other natural resources.

In spite of Peru’s substantial water resources overall, the populated desert coast experiences chronic water shortages. Irrigation has been a determining factor in increasing food security, growth of agricultural productivity, and human development in rural areas of the country. 60 percent of Peru’s land mass (73.3 million hectares) is covered by forests. Deforestation, at a rate of 0.2 percent per year, is the primary source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the country (MINAM, 2011). Land conflicts are common in Peru, with the most visible arising from exploitation of minerals and timber. The formal system of dispute resolution is not considered accessible by most of the population, especially the rural poor.

GDP growth is rebounding after a regional downturn in 2014. World Bank Forecasts indicate this trend will continue. Nonetheless, problems with inequality persist. Nationwide, the rates of total and extreme poverty were 21.77 percent and 4.1 percent (2015 data according to the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (Spanish acronym INEI). The rate of poverty in rural areas is almost triple the rate in urban areas (37.9 and 13.9, respectively), with the most extreme poverty found in remote rural areas among indigenous Peruvians.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

As Peru continues its programs to title land, and with pressure to develop natural resources (especially in the mining sector), tenure security will depend in part on the strength of its dispute resolution institutions. Accessibility continues to be a problem for Peru’s formal judicial system. The country’s informal systems have greater social legitimacy but lack formal authority and may not reflect the equitable principles of formal law. Donors could assist the government in strengthening both formal and informal institutions and creating a single, integrated framework to support the efficient and effective enforcement of land rights.

USAID‘s support for Peru‘s forest sector has provided concrete assistance to the National Agricultural Innovation Institute (Spanish acronym INIA), the National Forest and Wildlife Service (Spanish acronym SERFOR), forest communities, and concession holders. Forestland presents unique tenure issues, including competing claims to land and forest resources asserted by various interests. The continued decentralization of forest resource management is likely to require continued technical assistance and support for participatory processes that include local communities in mapping forest rights, establishing concessions, and decision making. Supporting forest governance is essential to fight deforestation as illegal logging accounts for 80 percent of the country’s forest loss. The WWF has listed the Amazon as one of the world’s top deforestation fronts. The region is also threatened by illegal gold mining which is exemplified by the invasion of the Tambopata National Reserve, an important protected area in the southern Peruvian Amazon (department of Madre de Dios). USAID and other donors could continue their technical assistance and support to local communities in managing forest resources, and could review achievements to date and lessons learned in order to inform continued and expanded support for this sector.

Recognition and protection of the use rights of peasant communities and indigenous people vis-à-vis conflicting legally or illegally acquired use or exploitation rights and other types of occupations. Considering there are several thousand peasant and indigenous communities in Peru, it is necessary to understand and strengthen their community and individual rights and clarify their land titles. Encouraging their inclusion in the discussion of public policy is important and could be supported by donor programs.

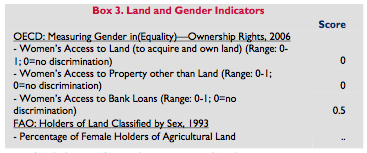

The Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Gender and Land Rights Database (GLRD) shows a number of fundamental barriers that prevent women from securing their rights to land and natural resources in Peru. Strengthening women’s land rights has been shown to have far reaching effects as women devote more of their income to family welfare with repercussions in childhood mortality rates, nutrition, education, and human capital development. Donors could engage the government and NGOs in raising awareness about the importance of women’s land rights and women’s participation in community-level resource governance.

Increasing resource extraction, especially in the mining sector, has produced tensions over the control of, and benefits related to, resources tied to land. Environmental and social safeguards have not always been respected and complacency in the public sector has generated local-level conflicts between the government and its citizens. Donors could promote best practices related to community consultation, participatory mapping and benefit sharing with the extractive industries. In the gold mining sector, the Better Gold Initiative (BGI) could be considered in future support activities of donors; and for hydrocarbon extractives, there are well established best practices in this sector, such as those realized in Loreto, Peru, one of the largest and most dynamic hydrocarbon zones in the Amazon (Finer, 2013). Also, donors could align work with strategies such as REDD+ and the Government of Canada’s project on sustainable extraction, to assess, improve and monitor environmental and social conditions related to artisanal-scale, medium-scale and large-scale mining.

Summary

Peru is one of the world’s most biodiverse countries, including in its territory portions of the Andes mountains and the Amazon rainforest, as well as coastal plains. The land provides a wealth of natural resources, including diverse forest products, a variety of minerals, and abundant water. Peru’s formal laws recognize the autonomy and rights of the country’s indigenous and peasant communities, which have the highest rates of poverty in the country. However, rural communities struggle to retain control of the land and natural resources that they depend on for their livelihoods. Peru is distinguished by its long-term efforts at agrarian reform. In the 1970s the government acquired and redistributed a substantial portion of the country’s agricultural land to landless and land-poor agricultural families. Beginning in the 1990s, the country undertook programs to develop cadastres and provide titles for rural and urban land. Roughly half the country’s land was titled as of 2007, and informal land rights in urban and peri-urban areas are being formalized. A consolidated program plans to expand into more remote rural areas. Women have received an increasing share of rights to agricultural land over the last decades, but they often continue to lack the power to manage and control land and natural resources.

Peru’s natural resources are endangered by land degradation, deforestation, and water pollution. Most of the country’s substantial water resources are located in the forest and mountain areas, which have low population densities. The populated coastal plains have chronic water shortages and are susceptible to El Niño floods.

Peru’s natural resources are endangered by land degradation, deforestation, and water pollution. Most of the country’s substantial water resources are located in the forest and mountain areas, which have low population densities. The populated coastal plains have chronic water shortages and are susceptible to El Niño floods.

In 2009, the government enacted a new water law that was designed to integrate the water sector, decentralize management of water resources to the river basin level, and provide for participatory community management of these resources.

More than half of Peru’s land mass is covered by forest. The government has been decentralizing the management of forestland, driving the need for capacity-building and institutional strengthening at local levels. Peru has a substantial and growing mineral, oil and gas sector, which accounts for almost half of all export earnings. Subsurface claims to mineral rights extend over 20 percent of the country’s land, and increased extraction has threatened both human and environmental health in mining communities. Land conflicts are common in Peru, with the most visible arising from exploitation of valuable minerals and timber. The formal system of dispute resolution is not considered accessible by most of the population, especially the rural poor.

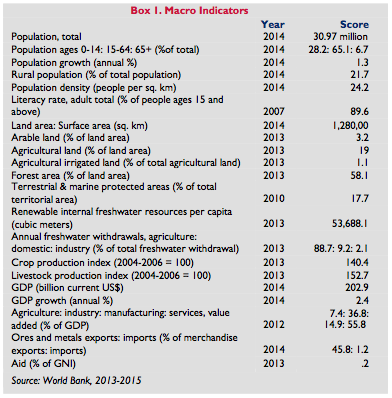

Land

Peru has a total land area of 1.2 million square kilometers. The country is home to 30.97 million people (2014), including 14 linguistic families and 44 ethnic groups. An estimated 45 percent of the population is indigenous, 37 percent mixed Indigenous-European, 15 percent European, and 3 percent other. Twenty-two percent of the population is rural. Annual GDP was US $203 billion in 2014, of which agriculture constituted 7 percent, services 55 percent, and industry 38 percent. In 2013, 23.9 percent of Peru’s population was poor; 4.7 percent was extremely poor. The rate of poverty in rural areas was triple the rate in urban areas (World Bank 2015; CIA 2013).

Approximately 19 percent of Peru’s total land is used for agriculture. Forests make up 58.1 percent (2013) of total land area, and protected areas make up more than 17 percent of total land area (World Bank 2015; SERNANP 2015).

Geographically, the country is divided into three regions: Costa; the long narrow Pacific coastal region; Sierra; the mountainous Andes region; and Selva; the rainforest region of the Amazon basin. Peru is among the world’s most biodiverse countries, although this status is threatened by deforestation and soil degradation. Direct drivers of deforestation, which is occurring at an annual rate of 0.2 percent, include new infrastructure development, expansion of the agricultural frontier, new settlements, mining and hydrocarbon exploitation, illegal mining, logging, and coca leaf cultivation. Interestingly, new highway construction, such as the North Interoceanic and Jorge Basadre highways, is the main driver of deforestation (Piu & Menton, 2014). This is due not only for the construction itself but the development that occurs as a result of the presence of the road. Seventy-five percent of deforestation in the Amazon region occurs within 20km of a road (Oliviera et al 2007). Mining is also a driver of deforestation. In the department of Madre de Dios alone, 50 thousand hectares of forest have been lost to illegal mining. Peru has very steep slopes, and its land is susceptible to erosion, seasonal rains, the effects of El Niño, and wind erosion near the coast. Overgrazing of livestock, deforestation, and poor cropping practices exacerbate these factors. (Che Piu and Menton 2014; World Bank 2006b; Tolmos and Elgegren 2006; USDOS 2010; MINAM 2015).

Geographically, the country is divided into three regions: Costa; the long narrow Pacific coastal region; Sierra; the mountainous Andes region; and Selva; the rainforest region of the Amazon basin. Peru is among the world’s most biodiverse countries, although this status is threatened by deforestation and soil degradation. Direct drivers of deforestation, which is occurring at an annual rate of 0.2 percent, include new infrastructure development, expansion of the agricultural frontier, new settlements, mining and hydrocarbon exploitation, illegal mining, logging, and coca leaf cultivation. Interestingly, new highway construction, such as the North Interoceanic and Jorge Basadre highways, is the main driver of deforestation (Piu & Menton, 2014). This is due not only for the construction itself but the development that occurs as a result of the presence of the road. Seventy-five percent of deforestation in the Amazon region occurs within 20km of a road (Oliviera et al 2007). Mining is also a driver of deforestation. In the department of Madre de Dios alone, 50 thousand hectares of forest have been lost to illegal mining. Peru has very steep slopes, and its land is susceptible to erosion, seasonal rains, the effects of El Niño, and wind erosion near the coast. Overgrazing of livestock, deforestation, and poor cropping practices exacerbate these factors. (Che Piu and Menton 2014; World Bank 2006b; Tolmos and Elgegren 2006; USDOS 2010; MINAM 2015).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Prior to agrarian reform in Peru, land tenure relations throughout the country were highly inequitable. One percent of landowners held 80 percent of the private land in large estates. In contrast, approximately 83 percent of farmers had farms averaging 5 hectares or less and they controlled 6 percent of total land. In some areas, such as the highland sierras, indigenous peasants cultivated small plots on large estates in exchange for labor on the estate. These peasants were essentially serfs and were not allowed to move. In addition, landowners could rotate or take away the peasants’ land at their discretion. In the mid-1960s, Peru was plagued by peasant unrest, resulting in land invasions and by leftist rebellions stemming in part from the archaic land tenure regime. Land reform was deemed necessary to avoid revolution (Albertus 2010).

During Peru’s period of agrarian reform (1969–1991), 38 percent of the country’s agricultural land was expropriated from large estates, rice mills and sugar refineries and redistributed to landless and land-poor agricultural families. Under the military regime (1968–1980), all landholdings larger than 150 hectares on the coast and 15-55 hectares in the sierras were subject to expropriation without exception. These ceilings were later lowered to 50 and 30 hectares, respectively. Compensation for the expropriated land was based on the value declared by the landowners for tax purposes, which averaged approximately 10 percent of the land’s actual value (Lastarria-Cornhiel and Barnes 1999; Albertus 2010). Although the reform ultimately failed to solve the problem of landlessness, it eliminated the vestiges of the feudal-like hacienda system and helped to prepare the way for a more market-oriented and technologically-responsive rural middle class.

Urban migration in Peru gained momentum in the 1940s. The legal and administrative framework of the formal land markets, which did not take into consideration the issue of recent migrants, indirectly excluded them, a result of which was that they began to build informal illegal settlements (Burns 2007).

Today, many poor households in Peru own at least some land, although in urban areas this land may be located in informal, or poorly-serviced residential areas. In 2014, approximately 76 percent of households owned their own home although roughly 44 percent lacked a property title. Nationwide, 6 percent of households are squatters (8 percent in Lima). While 66.3 percent of households have access to basic services, only 34.3 percent of poor households and 13 percent of extremely poor households do (Deere and Leon 2003; UN 1996; IADB 2007; MIDIS 2015; INEI).

According to the 2012 National Agricultural Census there were 2.2 million rural parcels in Peru of which 256,387 were held by peasant communities (comunidades campesinas) and native communities (comunidades nativas) (INEI 2012).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution of Peru (1993) guarantees all persons the right to own and inherit property. Law Decree No. 22175 (1978) and Law No. 24656 (1987) recognize the customs, practices and traditions of the native and peasant communities, respectively, and their rights to communal land (GOP Constitution of Peru 1993; GOP Law Decree No. 22175; GOP Law No. 24656).

For urban areas, Legislative Decree No. 495 (1988) recognizes possession rights to land by providing security to those people holding and legitimately occupying land but lacking formal documents of ownership (IADB 2007; Deere and Leon 2003). The subsequent Law No. 28687 (2006) prioritizes, as a national interest, the formalization and registration of informal housing on State land if it was occupied before December, 2004. Legislative Decree No.1202 (2015) extended the possession requirement for allocation of State-owned land to November 24th, 2010.

Legislative Decree No. 653 (1991) ended the period of agrarian reform in Peru by removing restrictions on the transfer of rural land. The decree permits the subdivision of land, land sales, transfers, rentals, mortgages, and inheritance. The Constitution (1993) establishes that the State supports agricultural development and guarantees the right of land ownership in private, communal, or any other association forms. Law No. 26505 (1995), known as the “Land Law” provided that beneficiaries of agrarian reforms would receive title to the allocated land and made special provisions for recognizing peasant and native communities’ holdings and established quorum requirements for the sale of communal land. Although the Land Law was amended several times by legislative decrees, social discontent led to the restoration of its provisions in 2009. More recently, the government passed Law N° 30230 (2014), which establishes a special procedure for formalizing plots located within the area of influence of public and private investment projects (Lastarria-Cornhiel and Barnes 1999; GOP Constitution of Peru 1993; IADB 2007; Deere and Leon 2003, CEPES 2015).

TENURE TYPES

Peru’s legal framework recognizes ownership, possession rights, leaseholds and communal rights to peasant and native community lands. Individual and collective property rights are regulated by the Civil Code (1984) and its complementary regulations. Ownership rights include the subsoil, surface, above the ground within the parameters of the Sec. 954 of the Civil Code.

Communal rights may be held by peasant and native communities and are regulated by their respective laws (GOP Constitution of Peru 1993, GOP Law Decree No. 22175 and GOP Law No. 24656). While peasant communities inhabit the coastal and highland regions, native communities inhabit the Amazon region. The 1993 Constitution provides that native and peasant communities are autonomous in their organization, communal work and in the use and free disposal of their lands, as well as in economic and administrative matters within the framework established by law. Law No. 26505 permits native and peasant communities to determine how they will hold land (i.e., communally or individually). However, the ownership of their land is inalienable, except in the case of abandonment (GOP Constitution of Peru 1993). The actual management and administration of communal land depends on local conditions including production opportunities, resources, local ecology, and historical use patterns (IADB 2007; Burneo de la Rocha 2005; Fuentes and Wiig 2009). The general assemblies of communities have the power to perform any other act regarding their rights over community lands. The assemblies in coastal communities must have a 50 percent majority support for their actions; in the highlands and the Amazon region, assemblies must have a two-thirds majority (GOP Law N° 26505).

The rights to all subsurface rights are held by the state in Peru, peasant and native communities do not own these rights. But they can obtain concession rights to exploit the natural resources associated with their lands (forest resources are handled differently and which only require administrative authorization). Forest lands within native communities cannot be titled. Instead use rights are awarded. (GOP Law Decree N° 22175).

Public agencies’ recognition of existing and registered peasant and native communities is inconsistent. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI) there are 4,160 peasants and 873 native communities with a registered title to land. However, COFOPRI and the National Superintendence of Public Registries (SUNARP) use higher numbers. This uncertainty complicates the implementation of public policies (World Bank 2015c).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

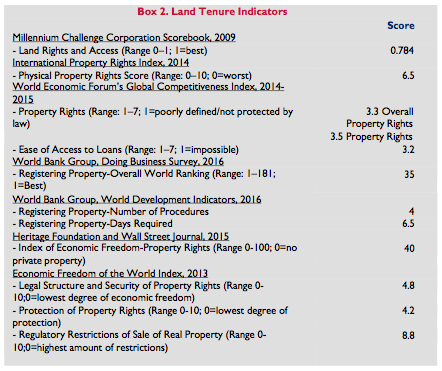

Registering property in Peru requires four procedures, takes an average of 6.5 days, and costs 3.3 percent of property value (GOP Supreme Decree No 032-2008-VIVIENDA; GOP Legislative Decree N° 1089, Deere and Leon 2003; World Bank 2016).

In Peru, methods of obtaining land rights include purchase, lease, state allocation, community allocation and, most commonly, inheritance. The Civil Code (1984) permits occupants of land to obtain a right of (adverse) possession after five to ten years, depending on the circumstances. Peru’s titling programs have also granted (adverse) possessory rights after occupancy of private land for five years and of State land for one year. However, Legislative Decree No. 1089 and Supreme Decree No. 032-2008-VIVIENDA set a limit to those terms, establishing that such possession should have occurred before December 13th, 2008 (Field 2003; Torero and Field 2005; Bandeira et al. 2010, IADB 2014, GOP Legislative Decree No. 1089; GOP Supreme Decree N° 032-2008-VIVIENDA).

The Special Land Titling and Cadastre Project (PETT) was initiated in 1992 as a branch of the Ministry of Agriculture with the objective of formalizing all rural land rights, including mapping land, creating a cadastre, and issuing and registering titles. As of 2007, PETT had provided formal titles on about 1.9 million plots of rural land, with over 1 million titles issued in the first stage of the project (1996–2002). A total of 55 percent of rural land plots were titled by 2012 as a result of PETT and follow-on registration projects. Much of the land titled in the highlands was titled as communal land, representing the land interests of numerous community members. Despite the progress achieved, it is estimated that in 2012 there were 944,337 untitled individual plots, of which 90 percent were in the highlands and Amazon regions. At the same time, it is estimated that 1000 native communities and 800 peasant communities, 45 percent and 15 percent, respectively, still lacked formal property titles.

There are conflicting studies about the impact of the land titling project. According to one study, over 83 percent of Peruvian households reported no increase in land-based investments after receiving titles, 80 percent reported no increase in use of new technology or in land-use intensity, and 72 percent reported no increase in agricultural yields (Bandeira et al. 2010). Observers have suggested several reasons for these findings, including a lack of agricultural financing and credit sources in rural areas, overlapping responsibilities of public agencies in charge of cadastral maps, and incomplete cadastre information, which may create a perception of insecurity by the land occupant. Furthermore, land titles lose value (and may be less secure) upon transfer if the new owner fails to register the land (Bandeira et al. 2010). However, another study shows a positive impact of titling in Peru, particularly on the use of agricultural inputs and agricultural investment, resulting in an increase in rural income (IADB 2014).

Urban property-rights reform, managed by the Organization for Formalization of Informal Property (COFOPRI), resulted in the distribution of almost 2 million property titles to squatters on public land. Roughly 6.3 million of the approximately 10 million urban residents received formal property rights and registered with the state. (Field 2003; Torero and Field 2005). As a result, 30 percent of urban land plots were titled by 2007. Between 2007 and 2014, an additional 730,000 plots were titled in marginal urban areas in Peru. (Molina 2014; Bandeira 2010).

Other means of acquiring land include land auctions for large-scale irrigation projects and adjudication of forest land for large scale agriculture, often palm oil. Both of these processes have raised questions of equity and consent. While bills have been introduced to prevent excesses, and social groups have called for a moratorium on new concessions, very little has been done legislatively to address these issues. (World Bank 2013b; Gestión 2015; Deininger 2011; Salazar 2012).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Marital property is governed by Article 5 of the Constitution, the Civil Code and by the Code of Commerce. Women have the legal right to own land in Peru, and all marital property is presumed to be joint marital property. Although marriages create a community property regime that cannot be renounced, property owned at the time of the marriage, gifts received during marriage, and money paid for insurance are considered separate property. In addition, some property obtained by one spouse during marriage may be deemed to be separate property depending on how it was obtained (Martindale-Hubbell 2008). De facto unions (co-habitation) are also recognized under a joint property regime when the union has lasted at least two continuous years. However, the absence of documentation can make it difficult to prove the duration of such unions (FAO 2013).

Marital property is governed by Article 5 of the Constitution, the Civil Code and by the Code of Commerce. Women have the legal right to own land in Peru, and all marital property is presumed to be joint marital property. Although marriages create a community property regime that cannot be renounced, property owned at the time of the marriage, gifts received during marriage, and money paid for insurance are considered separate property. In addition, some property obtained by one spouse during marriage may be deemed to be separate property depending on how it was obtained (Martindale-Hubbell 2008). De facto unions (co-habitation) are also recognized under a joint property regime when the union has lasted at least two continuous years. However, the absence of documentation can make it difficult to prove the duration of such unions (FAO 2013).

Joint titling of land to spouses was adopted in large-scale rural titling in Peru by Legislative Decree N° 667. Married persons and those in de facto relationships are obliged to identify and include their spouses when registering property. Recent studies suggest a growing number of husbands and wives holding joint title to land: in 2000 only 13 percent of titled land plots were held jointly. During the first stage of PETT (1993-2000), one pervasive impediment to listing women’s names on land titles was that many women in peasant and native communities lacked personal identification documents. This situation, however, has substantially improved. Currently, 98 percent of the population (94 percent of the extreme poor) possesses a national identification document. By the end of the second stage of PETT (2001-2006), joint titling accounted for 57 percent of the 1.5 million formalized agricultural plots (Fuentes and Wiig 2009; Deere and Leon 2003; MIDIS 2015; Hvalkof 2008; Wiig 2013).

Peru’s Constitution and the Civil Code (1984) govern the inheritance of land. The law provides that property can pass by will but requires a portion of the estate to pass to the “forced” heirs of the deceased: the children and other descendants, parents and other ancestors, and the spouse or the surviving member of a de facto union. Children inherit equally, regardless of sex. Surviving spouses receive the same share as a child, independent of the spouse’s interest in the joint marital property (GOP Civil Code).

Despite the gender-neutral legislative framework for land rights in Peru, traditional practices in rural and indigenous communities often discriminate against women and girls. In agricultural communities, daughters have traditionally married and moved outside their community of origin. Historically, families often denied daughters their right to inherit land because when they left the community their husbands’ families were expected to provide for them. Sons remained in their birth village after marriage and were expected to help with the agricultural land and care for their parents. As income sources have diversified and land is no longer the only indicator of power in a village, inheritance of land has become more egalitarian. Land rights now tend to be inherited based on opportunities and preferences as opposed to gender (Deere and Leon 2003).

Peru’s Law of Peasant Communities, No. 24656 (1987), which guarantees the integrity of communal property and recognizes the autonomy of peasant communities, also establishes that both women and men have the right to be community members with the right to use the goods and services of the community. However, to vote and participate in community decisions, one must be a qualified community member (comunero calificado). The customary practice is for one person in a household to hold this status, and the male head of household normally represents the family before the community. Although women are taking on increasing responsibility for agricultural work in Peru’s campesino communities, they have little say in community decisions concerning land and collectively managed natural resources (ARD 2006; Burneo de La Rocha 2005; Hvalkof 2008).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

In the last decade, land regularization functions have been the responsibility of different agencies. When PETT merged into COFOPRI in 2007, the rural land regularization function was transferred to this agency, which was under the Ministry of Housing, Construction, and Drainage. However, in 2009, following the mandate of the Decentralization Law, the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MINAGRI) approved the list of administrative functions to be transferred to the regional governments and this included rural land regularization. In 2011 the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) authorized the transfer of the budgetary resources from COFOPRI to the regional governments. Since 2013, MINAGRI is the governing agency regarding rural land regularization and is in charge of designing and implementing projects, in conjunction with the Regional Governments (GR), to improve services and rural land titling.

In 2014, MINAGRI created the Department of Regularization and Agricultural Property and Rural Cadastre (DSPICAR) to perform this function.

The decentralization process also resulted in the 2011 transfer of urban land regularization from COFOPRI to provincial and district municipalities (subsequent legislation extended – as a temporary provision – COFOPRI’s functions as central agency in charge of urban formalization through 2016). Currently, urban titling is a prerogative of the provincial and district municipalities, while rural titling is the responsibility of regional governments under the oversight of MINAGRI.

The Land Registry (Registro de Predios) is responsible for registering titles and is administered by the National Super Intendency of Public Registries (SUNARP), which operates in decentralized offices in different registry districts.

Some municipalities, including the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima, have set up Tax Service Administrations, which work as semi-autonomous local tax agents, responsible for administering local property tax collection, including the land tax, and receive a portion of the tax revenue that they collect (DIE 2007).

Community organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and in some cases private enterprises, have been instrumental in helping to formalize both rural and urban property in Peru (Lastarria-Cornhiel and Barnes 1999; Bury 2005).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

With the passage of Legislative Decree No. 653 in 1991, agricultural land could be freely sold, subdivided (with certain limitations on minimum parcel size), mortgaged, and rented. This decree thus lifted multiple restrictions on agricultural land transactions that were implemented during Peru’s agrarian reform. They constituted an initial step toward the establishment of a rural land market (Kagawa 2001; Field 2003; Lastarria-Cornhiel and Barnes 1999).

Whether Peru’s efforts to issue and register land titles over the past decade will result in strengthened land-market transactions is not yet clear. The World Bank Urban Property Rights Project, which recorded over 1 million property titles by 2004, reported in 2005 that land values had increased, and that around 630,000 of the titled properties had been transferred through market transactions. Other studies have confirmed a probable increase in land values for those with titles, at times by as much as 20–30 percent, but still note that Peru’s formal land market remains weak, and that neither transactions nor investments have substantially increased following titling efforts (World Bank 2005; Bandeira et al. 2010; Hvalkof 2008; Payne et al. 2009; Woolsey 2008).

One of the primary reasons for a stifled land market in Peru may be continued high land-transaction costs, caused by factors such as: (1) a relatively high land-transfer tax (at 3 percent Peru’s land transfer tax was over a point higher than the 1.9 percent average in developed countries); (2) a very low number of land registry offices (Peru has only a fraction of the registry offices, per area and number of people, of most developed countries); and (3) incomplete and overlapping cadastral information (Peru does not have cadastral coverage for those plots not yet registered, which increases required time for registration, especially in the case of a conflict over plot boundaries). One benefit to developing a universal cadastre could also be improved land-tax collection (for standing taxes, as opposed to the transfer taxes mentioned above), which could in turn stimulate the allocation of land to productive users on the land market (Bandeira et al. 2010; Payne et al. 2009).

As of 2007, the formalization of land titles had not increased mortgage lending. This indicates that access to loans in Peru is complicated by external factors rather than solely by (lack of) property title issues. Even though having a registered title increases land values by almost 34 percent – compared to plots that lack any kind of formal documentation – the probability of investing only increases by 5 percent (Fort 2008).

Only a small percentage of those with titles in Peru have used them as collateral. This could be because the demand for credit by most landowners is for small operational loans in amounts not suitable for mortgages. Most loans based on land rights, therefore, have not been mortgage-based but rather have been small loans where proof of title is used as evidence that the borrower has a stable domicile and the agricultural production capacity to repay. It is also worth considering that financial institutions are present in only 49 percent of Peru’s districts and that underserved areas tend to be rural (SBS 2014, Bandeira et al. 2010; UN-Habitat 2005).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Under Article 70 of the 1993 Constitution, property rights are inviolable and guaranteed by the State unless national security interests are involved. Property rights must be used in harmony with societal needs. Recently, Legislative Decree No. 1192 (2015) has repealed the General Law of Expropriation of 1999. The Law defines expropriation as the compulsory transfer of the right to private property, authorized only by an explicit act of Congress in favor of the State, at the initiative of the Executive, regional governments or local governments, regarding property required for the execution of infrastructure works or for other reasons of national security or public necessity declared by law; following cash payment of the appraised value including compensation for any damage to the expropriated person.

The Mining Law (Supreme Decree 014-92-EM of 1992) awards the holder of a mining concession the right to seek authorization from the mining authority to establish, on land owned by others, easements (servidumbres) that are necessary to make use of the concession right. An easement is established after the payment of compensation to the property owner. If the easement affects the property right, the mining authority may order the expropriation, ex officio or at the request of the concerned owner. However, the Constitution (1993) and the Land Law and its regulations repealed the expropriation provision used to benefit private industry.

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Land conflicts are common in Peru, with the most visible arising from the exploration and development of natural resources. Government concessions for oil and gas exploration (as noted above, Peru’s oil and gas resources are substantial), mining, biofuel production, and logging in areas where national parks, towns, farms and villages are located have resulted in local uprisings. Conflicts often reflect the fact that many oil and gas exploration plots are located in community territories and national parks – raising concerns that development will create negative impacts for communities and the environment. Indeed, mining operations are among the most prominent causes of land disputes. According to the Defensoría del Pueblo (Peru’s Ombudsman) in February, 2016 there were 208 social conflicts (142 active and 66 latent), of which 145 were of socio-environmental nature, 12 involved territorial demarcation, and 10 were related to communal issues. Among the socio-environmental conflicts, 91 cases were related to mining activities, 23 cases were related to hydrocarbon activities and 11 were related to energy activities. Most of the conflicts classified as “socio-environmental” occur in peasant and native communities, in areas where land tenure may be weaker (Defensoría del Pueblo 2015).

Legislative change has also caused conflict in Peru. In 2008, the GOP issued a series of decrees, primarily amending the forest and wildlife laws, that permitted the sale of communal lands by majority vote (reducing the 2/3 majority established by law). Indigenous groups protested, asserting that they had not been consulted. The protests were often violent – resulting in the deaths of 33 people in the province of Bagua in June, 2009, for example – and the government retracted some of its more controversial decrees (Economist 2009; Salazar 2010).

The protests led the Peruvian government to take several steps. In 2011, it enacted Law No. 29785, known as the “Prior Consultation Law,” which grants indigenous peoples the right to be consulted before the implementation of projects that could affect them. The State considers that a project needs to fulfill the requirements established both by the International Labor Organization’s Convention No. 169 and by the domestic legislation. The law explicitly leaves out protections for campesino communities, which are not considered indigenous (Khampuis 2012; Huguet Polo 2014; World Bank 2015c; GOP Law N° 29785).

Most Peruvians, and especially the poor, do not look to Peru’s formal judicial system to resolve land disputes. The regulatory framework governing the judicial sector is weak, and infrastructure has been neglected. The formal system has struggled to improve efficiency, professional competence, and address lack of public trust. The formal system is not considered accessible by most of the population, especially the rural poor (IADB 2007; World Bank 1997).

Conflicts over land in indigenous and peasant communities tend to be intra-community, especially where population increases and migration put pressure on scarce amounts of fertile or good-quality land. Virtually all active communal conflicts consisted of intra-community boundary disputes (Defensoria del Pueblo 2015). Private family conflicts are usually resolved by the extended family or by a council of elders. The political organs of the community, such as the General Assembly, deal with conflicts and disputes of wider community interest. Women in peasant and native communities often believe that they are not fairly treated by communal authorities in land-dispute resolution (Faundez 2003; Abusabal Sanchez 2001; Hvalkof 2008; Defensoría del Pueblo 2015).

Inhabitants of rural areas face linguistic, economic, cultural and geographical barriers that hinder access to justice. Moreover, the rural population is heterogeneous and therefore, groups have different cultural visions. Additionally, the judicial system is disjointed and does not extend across the entire territory. In practice this situation results in a replacement of State institutions by local organizations such as peasant patrols (rondas campesinas) and communal authorities, leading to “legal pluralism” or the coexistence of different normative orders in one socio-political space. Article 149 of the Constitution recognizes this pluralism and the legitimacy of communal authorities. It supports the exercise of jurisdiction, within their territories, by rondas to enforce customary law, provided they do not violate fundamental rights. However, the coordination between State justice and community justice systems has not been codified, and this lack of clarity causes frequent clashes between the systems (Benavides et al. 2015).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The Government of Peru has undertaken the largest land titling programs in South America. The first of these, the Special Rural Cadastre and Land Titling Project (PETT), focused on titling and developing a cadastre for all rural land. A second phase merged rural and urban land titling programs with a result that, as of 2007, approximately 53 percent of land in the country was titled (83 percent in the coast and 53 percent in the Andes). The third phase of the project, PTRT-3, currently underway, seeks to consolidate the registry and cadastre process and to formalize indigenous community land rights in Sierra and Selva (Torero and Field 2005; IADB 2007).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

The Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) is the main donor financing rural land titling programs (PETT), granting loans of US$ 21 million for the first stage (PTRT-I) in 1996 and US$ 23.3 million for the second stage (PTRT-2) in 2001. Together, PTRT-I and PTRT-2 surveyed three million rural parcels, registered 2 million property titles, and registered 540 peasant communities and 55 native communities. The third stage (PTRT-3), is under way and backed by a US$ 40 million loan. It takes into account lessons from the previous phases and focuses particularly on the communal titling of native and peasant communities and ensuring the sustainability of the rural cadastre.

The World Bank’s Urban Property Rights Project supported urban land titling from 1998 to 2004. The project reports recording over one million property titles, benefiting over 5.7 million Peruvians in marginal communities. The project received additional funding in 2005 for five additional years. The Real Property Rights Consolidation Project continued these efforts. Its objectives were to enhance the welfare of real property owners, facilitate access to economic opportunities, ensure the legal security of property rights, and complete conversion of informal tenure to formal tenure. The project also sought to establish cadastre services in urban and peri-urban areas among the participating municipalities and provide capacity building for provincial and district municipalities. The project helped to support a culture of formalization, increased property values, and improved the quality of life of the target population and supported Peru’s decentralization program by strengthening municipal institution. Project implementation was rated moderately satisfactory since the project failed to meet its end target for the migration of property registries and there were administrative irregularities that led to an investigation of fraud. (World Bank 2006a; World Bank 2005, World Bank 2013).

Between 2005 and 2009 the European Union (EU) funded a GTZ-implemented project entitled Supporting Reform of the Justice System in Peru. The project included an objective to improve legal access for Peruvians and building judicial capacity (GTZ 2009).

Several Peruvian NGOs have been active in land-rights issues. The civil society organization Peruvian Center for Social Studies (CEPES) is at the forefront of land-related issues and engages in matters of land reform and rural, indigenous, and environmental issues. The Land Group, or El Grupo ALLPA, supports land rights, rural development and farmer communities. Other organizations with a focus on land include the Association for Rural Education Services (SER) and the Center for Sociological, Economic, Political and Anthropological Studies (CISEPA-PUCP). The collective “Secure Territories for Peru’s Communities” (Territorios Seguros para las Comunidades del Perú) groups 27 organizations that represent or support native and peasant communities. Ensuring transferable property rights in Peru and throughout the developing world is among the three core areas of technical assistance provided by the Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD), founded by Hernando de Soto and based in Lima. ILD’s mission is to move assets of the poor from the extralegal economy into an inclusive market economy (ILC 2009; ILD 2008). Also, CooperAcción advocates for the rights of different collectivities and to promote the development of coastal and mining localities. (CooperAcción 2015; Territorios Seguros para las Comunidades del Perú 2015). Finally, it is important to highlight the work of the Instituto del Bien Común (IBC) in the development of an Information System on Native Communities of the Peruvian Amazon (Spanish acronym SICNA) which is a geo-referenced data base containing geographic and tabular information on native communities in the Peruvian Amazon. SICNA promotes land use planning and protection of rights of indigenous peoples, enabling the titling of native communities and the protection of indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation. SICNA was created to address the lack of official cadastral maps and accurate information on native communities in the Peruvian Amazon (IBC Peru, 2016).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Peru has the highest per capita availability of renewable freshwater in Latin America. In 2014, the per capita availability was 54,024 cubic meters (IADB 2015). The Peruvian territory is divided into three major river systems and watersheds. The Atlantic watershed (Amazon) represents 74 percent of the national territory and drains its waters through 84 hydrographic units. Due to heavy rains in the high and low jungle it provides on average 97.2 percent of the volume of water in the country. The Pacific Rim watershed represents 22 percent of the national territory and drains its waters into the Pacific Ocean through 62 rivers and streams, and provides 2.2 percent of the available water volume in the country. Finally, the Titicaca watershed is a closed hydrographic region that represents only 4 percent of the national territory and drains into Lake Titicaca through 13 rivers, and provides on average 0.6 percent of the total volume of water available in the country (FAO 2015).

Although Peru has the highest per capita availability of renewable fresh water in Latin America, the distribution of water resources is asymmetrical, resulting in chronic water shortages in the dry season. The coastal area has only 2900 cubic meters of water per person per year, but supports 59 percent of the population and generates the bulk of Peru’s GDP. In contrast, the tropical rain forest area has 80 percent of the country’s water resources (643,000 cubic meters per person per year) and supports 10 percent of the population (Bebbington and Williams 2008; World Bank 2006b).

Climate change could have dramatic effects on freshwater resources in Peru. Alterations in rainfall patterns have already triggered droughts and flooding and rising global temperatures are threatening glaciers, a major source of fresh water in the country (Glacier Hub 2015). Peru hosts approximately 71 percent of the world’s tropical glaciers and has recorded one of the highest rates of glacial retreat: about 500 square kilometers representing 22 percent of the area. This decline represents 7,000 million cubic meters of water, equivalent to the consumption of that resource in Lima for 10 years (ANA 2014).

According to the FAO (2015), water quality in Peru has declined due to the release of untreated effluents from mining, industry, municipalities, and agriculture. The FAO also indicates that of the 62 coastal rivers, 16 are partially contaminated with lead, manganese and iron (mainly caused by the mining sector) impacting the quality and cost of drinking water in coastal cities.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

According to the Constitution, the State holds sovereign rights to all renewable and nonrenewable natural resources in Peru, including water. Organic laws define the terms for their use and concession to private parties (GOP Constitution of Peru 1993; Portilla and Eguren 2007; Del Gatto et al. 2009).

After years of consideration, the General Water Law of 1969 was replaced by the Water Resources Law No. 29338 in 2009. The State Policy on Water Resources, also known as ‘Policy 33’, approved on August 14, 2012 contains guidelines for integrated water resources management. The strategy was adopted by Supreme Decree No. 006-2015-MINAGRI with the aim of ensuring, throughout the national territory, integrated management of water resources. The Supreme Decree 007-2015-MINAGRI regulates the procedures for formalization or regularization of water licenses (ANA 2015b).

TENURE ISSUES

As stated above, under the Constitution the state owns all renewable and nonrenewable natural resources. The Water Resources Law (2009), provides that water for primary uses (direct consumption, food preparation, personal hygiene, and religious and cultural rituals) from natural water sources and public waterways is available at no charge and does not require administrative approval. Productive uses of water, such as for agriculture and industry, are subject to regulation (GOP Constitution of Peru 1993; GOP Peru Water Resources Law 2009).

The Water Management Office, a dependency of the National Water Authority, is responsible for regulating the granting and formalization of water rights (ANA 2015b). According to the 2012 agriculture census, 700,217 hectares (28 percent) of the total area under irrigation have registered water rights. Water use rights have been formalized in 1,105 population centers (centros poblados), benefiting 332,814 people (ANA 2015b).

The Water Resources Law recognizes customary law governing water resources so long as it is not contrary to formal, statutory law. Under Peruvian customary water management systems, water rights are distributed to households within a community based on a hierarchical system. Existing water rights are often governed by turno, a right to irrigate a plot of land in rotation with other legitimate users of the same resource (GOP Peru Water Resources Law 2009a; Trawick 2003).

The number of communities using the resource often determines customary water management practices. Under one type of system, a single community shares a canal network and its water resources. Under a second system, different villages share one or more water sources, and the canal network encompasses more than one settlement. Communities will often employ an alternating water-use arrangement in which communities take turns using a given water source rather than dividing the flow (Trawick 2003).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The National Water Authority (ANA-under the Ministry of Agriculture), was created in 2008. It has a clear mandate for integrated and multi-sectorial water resource management, enjoys financial and administrative autonomy, and can issue sanctions through local offices in the river basins (World Bank 2009). The ANA is decentralized into14 Water Management Authorities, 72 Water Local Authorities and 6 Basin Water Resources Councils (ANA 2015a).

In addition to the ANA (and the Ministry of Agriculture) the Ministry of Environment (MINAM) and the Ministry of Health (MOH) also have critical water resource management responsibilities. MINAM is responsible for the generation of meteorological and hydrological information through its Meteorological and Hydrological National Service; while MOH has responsibilities related to water quality management (World Bank 2009).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS, AND INVESTMENTS

The most important contribution of the Water Resources Law (2009) was the inclusion of new and clearer strategies for water management, such as payment for use. However, the proper design and implementation of economic compensation for use and discharges remain a major challenge for ANA (Zegarra 2014).

With the support of the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the Government of Peru implemented a National Water Resources Management Modernization Project to improve the management of water resources by strengthening of the country’s capacity for participatory, integrated, basin-scale water resources management (WRM) at the national/central level and in selected river basins (World Bank 2015).

One of the main outcomes of the project was the creation of a River Basin Council (RBC) in each of three pilot river basins. The RBCs are responsible for drafting river basin plans and coordinating their implementation. Another significant project achievement to date is the development of a methodology for water use and pollution charges, approved in December 2012. Today, these charges account for 75 percent of ANA’s revenues, far more than the share of agency revenue received from the national budget (World Bank 2015a).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The World Bank has supported environmental governance in Peru with a three-phase Environmental Development Policy Loan Program (ENVDPL) and the ongoing Optimization of Lima Water and Sewerage Systems (WSS) Project to improve the efficiency, continuity, and reliability of water supply and sanitation services in the northern service area of Lima (World Bank 2015b).

One of USAID’s development objectives (DO) in Peru concerns the sustainable management of natural resources in the Amazon Basin and glacier highlands. Significant USAID investments are being made to address global climate change adaptation programming to address threats, including water management issues, associated with glacier melting in the Andean regions of Piura, Ancash, and Arequipa (USAID 2015).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Peru has nearly 73.3 million hectares of natural forest that cover 60 percent of its national territory, giving Peru the second most extensive forest cover in Latin America. The northern coastal region has relatively large areas of productive, floristically homogeneous forest. These forests are classified as mangrove, closed dry forest, dry savanna forest, and scrub. The forest region in the eastern section of the country (Selva) is totally covered by natural forest, which is generally classified as tropical moist forest, subtropical moist forest, tropical wet forest and subtropical wet forest (World Bank 2006b; FAO 2010).

Forests contribute 1.1 percent of GDP and provide 31,000 jobs (0.3 percent of the total) but receive only 0.01 percent of foreign direct investment (World Bank 2014).

Forests are classified as production forests (for timber and non-timber forest products), protected forests (e.g. parks and reserves) or peasant and native communal forests (CIFOR, 2014). In 2014 there were 16.8 million hectares of permanent production forests allocated to forestry production through the concession system.

In 2015 there are 76 protected areas in Peru (approximately 17 percent of the total land mass) in places as diverse as the rain forest and the coastal desert (WWF 2015; SERNANP 2015). These protected areas include national parks, reserves, sanctuaries and six specific areas of forest protection. The latter cover an area of 389,986 hectares, equivalent to 0.30 percent of the country’s total surface (SERNANP 2015).

The Government’s goal is to reduce the deforestation rate to zero in an area of 54 million hectares of primary forest by 2021. They have started the process of preparing for REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) at the national and subnational levels (Che Piu and Menton 2013). However, it is important to note that deforestation in Peru has been increasing during the past decade, by some estimates the annual forest loss has multiplied by nearly 3 times since 2001 (Butler, 2015). As the Washington Post reported, in Colombia, Peru, Bolivia and the other five nations whose territories cover 40 percent of the Amazon basin, the loss of vegetation increased threefold, wiping out a combined area of forest cover larger than the state of Maryland. In 2013-2014, the pace of deforestation in those nations jumped 120 percent (Miroff, 2014).

In January 2016, Peru joined Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia and Mexico as one of the few countries with a Baseline for Emissions from Deforestation. This tool will be used to measure, report, and verify any reduction in forest carbon emissions and will allow Peru to implement REDD+ activities to slow, stop and reverse the loss of its forests (Ministry of Environment 2015a).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The legal framework for forestry rights in Peru is complex and often contradictory. According to the Constitution, ownership rights to natural resources (including forests) belong to the state. The Constitution also recognizes the need to protect the environment in Peru for all Peruvians (SINANPE 2009; World Bank 2006b; Del Gatto et al. 2009; Portilla 2007).

Important laws establishing forestry rights include:

- The Environmental and Natural Resources Code (Legislative Decree No. 613, 1990);

- The Natural Protected Areas Law (Law No. 26834, 1997);

- The Forestry and Wildlife Law (Law No. 29763, 2011);

- The National System for Environmental Impact Evaluation Law (Law No. 27446, 2001);

- The National Environmental Management System Framework Law (Law No. 28245, 2004); and

- The General Law of the Environment (Law No. 28611, 2005). (Portilla and Eguren 2007)

The Forestry and Wildlife Law (2011) broadens the rights and duties established in the previous legislation and includes aspects of forest governance while addressing questions of equity and social inclusion. Free, Prior and Informed Consent is referenced in the law in line with ILO Convention No. 169, and is codified by the Consulta Previa Law (REDD desk 2013). Accompanying regulations to the Forestry and Wildlife Law were enacted in September 2015.

TENURE ISSUES

The Peruvian Constitution states that all natural resources, including forests, belong to the State. Most forests are located on public lands, and the state may grant use rights to the private sector through time-limited concessions. Publicly owned forest land includes permanent production forests, conservation concessions, natural protected areas, and state reserves. Privately owned categories include land held by Amazonian indigenous communities, Andean peasant communities, private conservation areas, and private agriculture plots (World Bank 2006b; Portilla and Eguren 2007).

Only the government has the power to grant forest concessions. These concessions do not constitute ownership rights and are for a limited duration (REDD desk 2015). Land granted as a concession can be used for timber extraction however it cannot be cleared for agriculture. Unfortunately, common practice frequently runs counter to the official law and forestry concessions have been misused, leading to land use changes (Che Piu and Menton 2013).

Peasant and native communities have exclusive use rights over the assets and services of forest ecosystems and other ecosystems within their lands and within other areas as designated by the State. However, in order to use the forest resources and wildlife in their lands, communities must request permission from forestry and wildlife authorities. In many indigenous communities in Peru, forests are governed by customary law and are considered community resources subject to community jurisdiction. However, individual families will often use forest resources on or near their land for cultivation and selective tree-cutting (FAO 1993).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Forest and Wildlife Law created the National Forest and Wildlife Service (SERFOR), as the national authority responsible for promoting the conservation, protection, growth and sustainable use of forests and wildlife. SERFOR has also a high-level advisory commission called CONAFOR (National Forestry and Wildlife Commission). Under the leadership of SERFOR, the same law also created the National System for Management of Forestry and Wildlife (SINAFOR), integrating all ministries, agencies and the national, regional and local public institutions that regulate forest management.

The implementation of strategies and management plans for protected areas and forest concessions is the responsibility of the National Service of Protected Natural Areas (SERNANP) and the Forestry and Wildlife Resources Supervisory Body (OSINFOR) respectively (the REDD desk 2015).

SERNANP is a specialized public agency under the Ministry of Environment (MINAM). Its main function is the management of the National System of Protected Natural Areas (SINANPE). OSINFOR, on the other hand, is responsible for supervising forest concessions and monitoring the sustainable use and conservation of forest resources, wildlife, and forest environmental services.

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS, AND INVESTMENTS

In general terms, Peru is moving forward in reforming its institutional and regulatory framework for the agriculture sector, specifically with a goal of reducing deforestation and forest degradation (the REDD Desk 2015).

Peru participates in many REDD+ readiness initiatives (e.g., Forest Carbon Partnership Facility; United Nations Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) and receives international cooperation funds to further support readiness activities (CIFOR, 2015a). The main public agencies involved in the implementation of REDD+ in Peru are the Ministry of Environment (MINAM), the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MINAGRI) and the Regional Governments (The REDD desk 2015).

The GOP has signed and ratified a number of international treaties to preserve the country’s environmental, natural and cultural heritage. Additionally, it has signed regional and bilateral agreements for the export and import of goods and services with tariff benefits. The Free Trade Agreement signed with the United States has been a driving force in the forest sector, prompting the updating of forest legislation and monitoring of the legal origin of forest and wildlife resources (Forest Transparency 2015).

STRATEGIES ON CLIMATE CHANGE

Two important reports on the impacts of climate change, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Special Report on Emissions Scenarios and the Stern Review, suggest that Peru will be one of the countries most affected by climate change (PSG, 2015). Figures from the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios indicate that in South America Peru will see the greatest temperature rise due to climate change. Their figures predict a dry season average temperature increase of between 0.7°C and 1.8°C by 2020 and between 1°C and 4°C by 2050 (PSG, 2015).

Much of the problem has to do with greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions due to deforestation. Peru is responsible for just .02 percent of global C02 but according to Peru’s First Biennial Update Report, deforestation comprises 35 percent of that total (Lima COP20, 2014).

According to a 2015 CIFOR policy paper there are two salient issues for improving climate outcomes from forest management: 1) entering into a dialogue considering key stakeholder goals to assess tradeoffs, and 2) mainstreaming the climate change discussion into sectoral policies (CIFOR, 2015b).

While there is no law on climate change in Peru, there are a number of policies directed towards climate change. The National Climate Change Strategy is the most explicit and establishes a framework and guidelines for mitigating climate change and reducing emissions (LIMA COP20, 2014).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Effective management of natural resources is a key national development objective. USAID/Peru will spend approximately 80 percent of all environmental funding on forest-related sustainable landscapes and biodiversity programs in the Peruvian Amazon Basin. There is also an ongoing USAID project called ‘The Peru Bosques Project,’ which runs from July 2011 to October 2016, and is designed to achieve: a) a legal and regulatory framework to protect Peru’s forest sector; 2) sustainable conservation of biodiversity in the country’s Amazonian forests; and 3) increased economic opportunities for businesses and native communities that make products from the forests’ natural resources (USAID 2015).

In 2013 Peru secured $50 million in funding from the Forest Investment Program (FIP) in coordination with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the World Bank (IBRD), other development partners and key Peruvian stakeholders (World Bank, 2014). The fund is for investments in activities fighting forest degradation and deforestation nationwide.

The Rainforest Alliance’s Training, Extension, Enterprises and Sourcing (TREES) program, which works in collaboration with a consortium of organizations under the umbrella of the Initiative for Conservation in the Andean Amazon (ICAA) Project, focuses on helping communities improve capacities to achieve sustainable forestry and build up competitive locally-owned forest enterprises (Rainforest Alliance 2015).

The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the Hatoyama Initiative (Fast Start Finance) of the Government of Japan are financing the Forest Conservation Program for Climate Change Mitigation – an initiative to reduce the problem of greenhouse gases emissions by including native communities and farmers.

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Peru is the world’s third-largest producer of silver, zinc cooper and tin, the fourth-largest producer of lead, and the seventh-largest producer of gold (UNFPA 2015). As of 2014, the mining industry accounted for 52 percent of Peru’s exports with a value of US$ 20.5 billion. The extraction of oil, gas, minerals and related services in Peru represented 10.4 percent of the overall GDP for the same period (UNFPA 2015).

Since 1991, mining claims throughout the country have increased from 2.2 million to 25.9 million hectares. Approximately 20 percent of all land in the country is covered by sub-surface mineral rights claims, according to the Geological Mining and Metallurgical Institute (2014). These claims have increased most rapidly in the highlands, where large-scale mineral operations have been privatized or where new mineral resources are likely to be developed in the near future. Over 95 percent of mining interests are held by private firms (Bury 2005). These claims are the source of conflict in the country as many oil and gas exploration plots overlap with community territories and national parks. Concerns over social-environmental impacts lead to protests that, at times, turn violent.

Peru’s oil and gas resources are substantial. It is possible that the country’s crude oil reserves top 5,864 million barrels. The country’s legal framework favors investors in the oil and gas sector, and there are several foreign investors involved in exploration and extraction activities. Between 2000 and 2006, the government increased the number of approved oil development lots from 30 to 151; exploration permits now cover an estimated 89 percent of Peru’s Amazon region (Gurmendi 2005; Salazar 2010).

The country’s mining sector includes large-scale operations, which are generally run by foreign companies, often in partnership with local firms. Large-scale operations are the country’s leading producers of gold and copper. They typically use open-pit methods. Environmental issues associated with this production includes the risk of cyanide or acid solution leaks, leaching of waste materials, dust, noise, and disruptions of the local topography. Medium-scale mines tend to be owned by Peruvian companies.

Most of their production comes from underground mines. In general, the medium-sized companies have less capacity and fewer resources to meet environmental standards. Small-scale and artisanal mining operations, almost entirely dedicated to gold mining, are run by individuals and often use methods that can cause substantial environmental damage (World Bank 2005). Factors such as the rising price of gold, easily exploitable deposits, and migration have increased the amount of artisanal mining in Peru (Peruvian Society for Environmental Law 2014).

Mining and smelting operations have significant impacts on the livelihoods of local residents and often are related to social tensions. In the six years between 2008 and 2014, 134 social conflicts related to the use or control of natural resources were registered. Frequently these conflicts are between native or indigenous communities and mining or oil companies (World Bank 2015c).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1993 Constitution establishes the Government’s obligation to promote sustainable use of natural resources and promote conservation of biodiversity and protected areas through a defined environmental policy (World Bank 2005).

However, Constitutional provisions exist alongside the institutional framework for mining activities in Peru, which was reformed in the early 1990s to promote foreign investment. The General Mining Law, passed in 1992 is the main legal instrument governing mining activities. Additionally, Legislative Decree No. 708 of 1992 promotes investment in the mining sector.

In December 2011, Congress passed Law No. 29815, which delegated legislative powers to the Executive to address illegal mining. As a result, the Executive issued legislation establishing the formalization process for small-scale and artisanal mining. One of the main issues introduced by this set of rules was the distinction of “informal mining” and “illegal mining.”

TENURE ISSUES

Mineral deposits, including geothermic areas, belong to the State and cannot be alienated or acquired by adverse possession (Martindale-Hubbell 2008).

The state grants concessions for the exploration and development of mineral resources to nationals, foreign nationals, or juridical persons. Concession rights are registered in the public registry and may be pledged as collateral. Concessions are granted for areas between 100 and 1000 hectares in grids or groups of adjoining grids. There are no legal restrictions regarding the number of concessions that a petitioner may request. The concession grants the holder the exclusive right to explore and exploit the mineral substances in the subsoil. Most concessions that are applied for are granted. However, the concession by itself is not enough to initiate exploration and exploitation activities. To do this, the group or individual holding the concession must also obtain a number of authorizations, permits and licenses from the GOP and the surface landowner (World Bank 2015c).

The increase in informal mining poses a tenure challenge as unfortunately many miners are not informed of the environmental damages they are causing and therefore do not treat their runoff. This transfers the responsibility for environmental remediation to the state. In order to address this problem, the government launched a program to formalize artisanal mining but this has yet to show the expected results (KPMG 2015).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

There are two options for granting mining concessions. The GOP, through the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MOE) and the Geological Mining and Metallurgical Institute of Peru (INGEMMET), is responsible for large and medium concessions. Small and artisanal mining are the responsibility of the Regional Governments through the Regional Mining Offices (World Bank 2015c).

Other relevant institutions for the mining sector in Peru are the Geological Society of Peru; the National Society of Mining, Petroleum and Energy – SNMPE; and the Peruvian Institute of Mining Security.

Additionally, the Ministry of Environment (Spanish acronym MINAM) through the Environmental Evaluation and Supervision (Spanish acronym, OEFA) plays an important role in balancing private investment activities and environmental protection. OEFA investigates the possible commission of administrative violations and can impose sanctions as well as preventive and corrective measures.

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS, AND INVESTMENTS

The GOP has taken substantive steps to improve the governance of, and diffuse social tensions related to, extractive industries (EI). These measures include the creation of the MOE in 2008, compliance with the EITI and other regulatory steps that oblige consultation with indigenous communities about proposed extractive activities in their territories. (World Bank 2015c).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Mining activity has been one of the main drivers of the Peruvian economy over the last decade. Between 2003 and 2012, investment in mining has grown by more than 2,700 percent, from US$ 305 million to US$ 8,568 million. Mining activities contribute almost 15 percent to Peru’s gross domestic product (GDP) and generates up to 16 percent of all tax revenues for the country (according to 2015 data). The mining industry is Peru’s primary export industry and it supports more than 200,000 direct jobs.

With strong domestic-driven economic growth, Peru’s private sector is increasingly engaging in corporate social responsibility (CSR). An example of that, was the mining sector’s Solidarity Fund (or Aporte Voluntario) which, between 2007 and 2011, disbursed US$ 596.7 million for education, health, and economic growth projects. In addition, as part of their concession contracts, some mining companies have established development funds that have disbursed US$ 266 million for social investment and income-generation programs. The growing interest in CSR has helped USAID develop private sector alliances and leverage close to US$ 25 million in private sector resources over the last several years (USAID 2012).

The Government of Canada also supports the GOP to sustainably develop the extractive and natural resources sector, especially mining, through the project Promoting Economic Competitiveness and Diversification in Extractive Regions (Canada 2015).