Published / Updated: December 2010

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

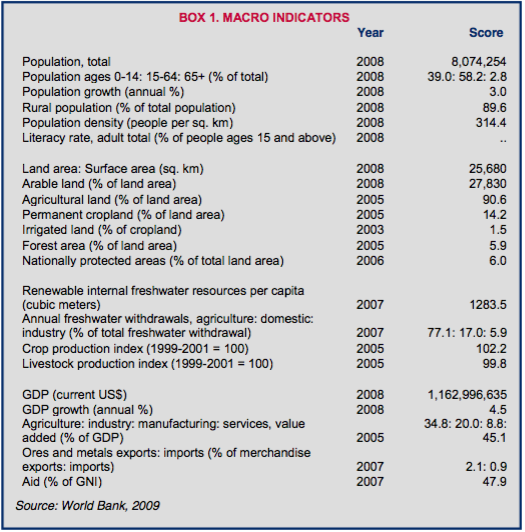

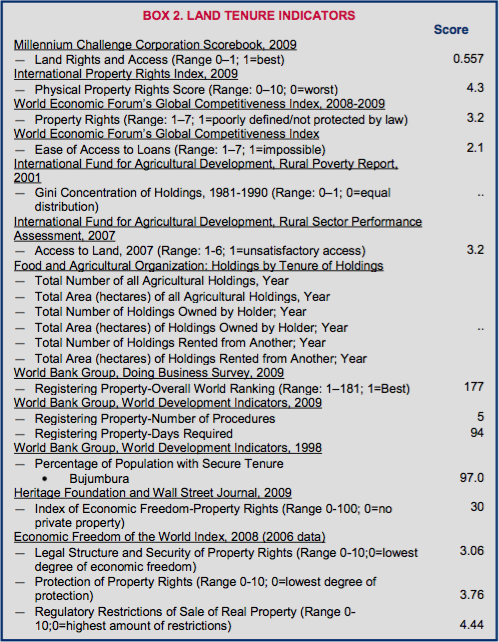

Burundi’s history of political conflict over the last 50 years has revolved in large measure around issues of access to land for agriculture. With a rapidly growing population of 8 million people overwhelmingly dependent on farming for employment and incomes, the ability of Burundi’s government to resolve outstanding disputes over rural land will be critical to political stability as well as economic growth. Repeated episodes of population displacements due to conflict, an already high level of population density, traditional laws and customs that discriminate against women’s ownership of land and other fixed assets, and the inter-linking of ethnic identities with access to land and other resources: all of these factors challenge the abilities of the government and its donor-partners to develop a satisfactory property rights regime and provide adequate resource governance in Burundi. Further, recent reports of increased investments in mining activities and the potential for petroleum extraction may generate new opportunities for conflict over natural resources.

Donors have stepped up their support for Burundi’s efforts to address land ownership and management issues since the election of 2005. Efforts have included: providing financial and technical assistance for drafting a new Land Code and for developing the dispute resolution work of the National Commission

Key Issues and Opportunities for Intervention

In order to realize stronger economic growth while maintaining peace and security, Burundi’s institutions for land administration, adjudication and dispute settlement, and the continued development of a new legal framework governing property rights will need substantial financial support as well as technical assistance. As a matter of priority, support might be targeted at:

Burundi is at a critical juncture regarding land access and tenure security. Reinvigoration of the Government’s effort to draft and pass a land code is a priority, followed by a long-term institutional and financial commitment from the international donor community. Once a land code passes, the GOB will need technical and financial assistance in drafting complementary legislation and implementing decrees, conducting a country-wide public information and awareness campaign to the population and civil society, training government administrative and judicial personnel on the law, and resolving land disputes that pre- date the code and/or those that arise due to new code provisions. The GOB will also need technical and financial assistance to build the capacity of new or newly reconfigured institutions charged with implementing different aspects of the law, particularly those related to land administration.

The work of the National Commission for Land and Other Property (CNTB) has already demonstrated some results but much remains to be done. Some have suggested that the traditional Bashingantahe’s capacities should be strengthened to permit disputes to be settled at the local level. In addition to providing financial support for the work of these organizations, donors could provide expanded training on conflict-resolution methods as well as helping them to ensure that the basic constitutional principles of equality and fairness are reflected in decision-making.

This is especially important for women being repatriated from camps of displaced persons and a relatively large population of widowed women, but is also important for ensuring that the principles of the Burundian constitution regarding individuals’ property rights are translated into reality. Donors have already begun to work with civil society organizations and have supported pilot efforts to reintegrate women into rural lives. Sustained support for expanded efforts is needed to have a greater impact.

There is growing evidence of excessive erosion in denuded watersheds, increased use of wetlands for production, and awareness that drought can threaten overall productivity. If Burundi’s nickel resources are exploited in the coming decade, these mining operations are also likely to have an impact on water use and quality. Donor support for assessing and reforming the existing institutional and legal frameworks governing water could held to ensure a more equitable and sustainable situation going forward. This initiative could also link with a forestry initiative, as protection of upper watersheds through afforestation is likely to be an important approach to better water management.

Summary

Since Burundi’s independence in 1962, ethnically based political parties have vied for control of the country, resulting in decades of violent conflict. Families have been forced to flee successive waves of conflict, and tens of thousands have been internally displaced or temporarily resettled in neighboring countries. Lands left by refugees and displaced persons have since been occupied by other families. As a result, rights for returnees are uncertain, and disputes are common. Continued risk of violent conflict in rural areas impedes development and hinders a reduction of government spending on security measures, to the detriment of pro-poor programs.

Since the 2005 elections and a 2006 ceasefire, a fragile peace has existed in Burundi. Some incidents of violence occur, such as in April 2008 when rebels fired on the capital, but sustained conflict has not resumed. In mid-2010, the national elections held in the country were marred by pre- election violence and resulting low turnout. The ruling party retained control of the country, and despite allegations by opposition parties of election abuses, international election observers concluded that the election procedures were transparent and conducted peacefully.

Land

LAND USE

Burundi’s total land area is approximately 25,700 square kilometers, 91% of which is classified as agricultural land. As of 2007, 90% of Burundi’s 8 million people lived in rural areas. Burundi’s mild climate and adequate rainfall provide an environment suited to intensive agriculture. Cash crops include coffee, tea, cotton, tobacco, and sugarcane. Subsistence crops include bananas, maize, manioc, sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes, beans, peas, wheat, peanuts, vegetables, plantains, livestock, and fish. Ninety-four percent of Burundi’s working population is engaged in growing food crops (Banderembako 2006; World Bank 2009a; WFP 2010).

In spite of this emphasis on agriculture, Burundi’s population suffers from significant poverty and food insecurity. Approximately 67% of the population lives below the poverty line and many live in extreme poverty. Roughly 63% of the population suffers from food insecurity, although there is substantial regional variation. Burundi ranks 167th out of 177 countries on the 2007/2008 Human Development Index (World Bank 2008a).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Burundi straddles the Nile and Congo basins and has abundant groundwater and freshwater resources. The country has three large lakes, including Lake Tanganyika (one of the world’s largest freshwater lakes) and significant wetlands and marshland. Most of the country receives between 1300–1600 millimeters of rainfall per year, with the wettest areas in the northwest (Hobbs and Knausenberger 2003; Banderembako 2006; World Bank 2008a; GIEWS 2010).

Despite these significant resources, access to water in Burundi has been challenged: the country experienced several droughts between 2004 and 2006; marshes and wetlands have been drained or used seasonally for agricultural production; and infrastructure for water delivery fell into serious disrepair or was destroyed during the conflicts in the 1990s and early 2000s. Urban water supply in Burundi dropped from over 70% coverage in 1993 to 60% coverage in 2008. In rural areas, 40% of the population has access to safe drinking water. In a World Bank Institute study, 50% of respondents reported paying bribes to obtain access to safe drinking water. Between 66% and 78% of all reported illnesses are the result of lack of access to safe drinking water and sanitation (Hobbs and Knausenberger 2003; Banderembako 2006; World Bank 2008a).

Water use in Burundi is shared by the following sectors: agriculture (77%), domestic (17%), and industry (6%). Irrigation is limited to surface irrigation (ponds

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

About 6% of Burundi’s total land (152,000 hectares) is forest, only 14% of which is natural forest. The balance is plantation forest, which has been expanding since 2000 in an effort to meet the needs of the population for fuelwood and timber and to restore tree cover. Most of the country’s remaining natural forest is found along the Congo-Nile ridge, which has dense montane forests in the highlands and xerophilous vegetation on the summits. The western plains have some original savanna forests and semi-deciduous forests along Lake Tanganyika and in the southern region, a nature reserve protects 3000 hectares of primarily montane forest (Athman et al. 2006; Koyo 2004).

Protected areas cover 4.5% of the total land and include national parks, reserves, and protected landscapes, which are forested tracts intermixed with agricultural land. The country’s largest national park, Ruvubu, covers 50,800 hectares in the northeastern part of the country and includes tree savanna, open forests, gallery forests, and swamps. The mountainous Kibira National Park spans 40,000 hectares in northwestern Burundi and is the source of two-thirds of Burundi’s water. Half of Burundi’s hydroelectric energy is produced by the park’s dam. Together with Nyungwe National Park across the border in Rwanda, Kibira is the largest remaining tract of mountain forest in East Africa and considered the most wildlife-rich ecosystem in the Albertine Rift (a network of valleys in Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo). The Kibira National Park is home to 98 species of mammals, including rare owl-faced monkeys, 200 species of birds, and 644 plant species (Nzojibwami 2003; IRIN 2002).

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Although Burundi is not a globally significant producer or consumer of minerals, the country has commercial quantities of nickel (6% of known world reserves), phosphates, vanadium, peat, and alluvial gold, and niobium and tantalum are produced on an artisanal scale. The country also has deposits of iron, limestone, uranium, titanium, carbonatites, and cassiterite under varying exploration and production efforts. Burundi exported 2170 kilograms of gold in 2008, with between a quarter and a half produced by artisanal miners. Most mining takes place in Kirundo, Kayanza, Muyinga, and Citiboke provinces (Yager 2009; GOB 2006).

Only a small number of companies are active in Burundi’s mining sector, although the number of foreign companies engaged in exploration is increasing. The privately owned company Comptoir Minier des Exploitations du Burundi SA (COMEBU) is mining gold, niobium, tin, tungsten, and tantalum. The State- owned Office National de la Tourbe (ONATOUR) produces peat, and artisanal miners produce alluvial gold. The government awarded the British company Surestream Petroleum Ltd. exploration licenses on land near Lake Tanganyika. The company is proceeding with its environmental impact assessment in 2010, with a seismic study to follow in 2011. The government identifies the lack of sufficient, reliable energy as the biggest challenge to growth in the sector (Yager 2009; Backer and Binyingo 2008; Davenport 2008; Surestream 2010).