Published / Updated: May 2018

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

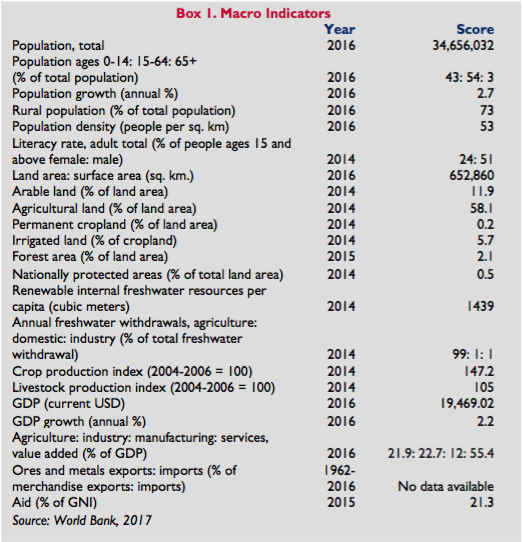

Afghanistan continues to struggle to overcome decades of war and civil strife. Its political context remains complex and dominated by the Taliban insurgency, narcotics production, weak governance and incomplete rule of law. After more than fifteen years of state building Afghanistan remains a fragile state. Population displacement within and outside of Afghanistan, internal land use conflicts, changes in national political and economic ideologies, weak natural resource governance, variable climatic conditions (including drought), climate changes and land grabbing have resulted in a complex and unsettled land ownership and management situation. Land rights are perceived to be highly insecure and disputes are widespread. This instability undermines prospects for the greater investment needed to increase agricultural productivity, sustainably manage natural resources and enhance economic recovery in both rural and urban areas. It also increases the vulnerability of millions of Afghan households, especially women and children, to poverty and exploitation.

Since the Bonn Agreement in 2001, the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA), with assistance from the international community, has worked to: (1) restart economic growth, especially in the agricultural sector and through the rehabilitation of irrigable land; (2) develop local institutions capable of meeting the population’s health and education needs; and (3) strengthen land tenure security through improvements to the legal framework, the implementation of a country-wide land survey, mapping and registration system, and the regularization of land rights in informal settlements. But economic growth and political stability will not be achieved unless and until the GIRoA removes constraints on access to land (especially urban and irrigated agricultural land), provides functional mechanisms to resolve disputes among competing claimants and provides tenure security to owners, lessees and all of those along the continuum of land rights holders in Afghanistan.

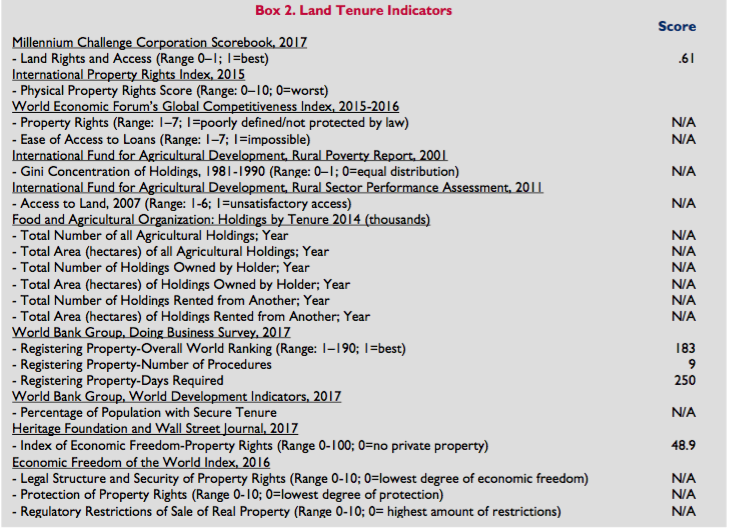

A new Constitution enacted in 2004 sought to establish a legal framework for property rights that safeguards the right of individuals to own property. The 2007 Land Policy addressed bottlenecks in land rights administration and the overlapping authority of institutions and was followed by the 2008 Law on Managing Land Affairs, which lays out principles of land classification and documentation, governs settlement of land-rights disputes and encourages commercial investment in state-owned agricultural land with opportunities for long leases. The strategic vision for the Afghanistan Independent Land Authority (ARAZI) is to provide a balanced approach between (a) pro-poor land administration services in support of individual and collective tenure security through land registration, and (b) land allocation and the provision of land to support private sector investment in infrastructure, natural resources, agriculture and industry. The Ministry of Justice, however, estimates that 90 percent of Afghans continue to rely on customary law and local dispute-resolution mechanisms. Local customary systems are stressed by the need to manage the layers of competing interests: populations have moved to urban areas to avoid conflict and seek livelihoods, and populations displaced by earlier conflicts have made efforts to reclaim both rural and urban properties.

Afghanistan’s development depends to a large extent on the efficient use of its land resources. Demand for agriculture land and for commercial development is high. Natural resources (including extractives) and agriculture are the main sectors with the potential to drive the required growth. However, water is scarce and decayed infrastructure systems remain key challenges for the country. The discovery of extensive mineral resources will put more pressure on the land sector. Mineral resources increase the value of land, intensifying the need to resolve competing claims, to secure land rights for local populations (paying particular attention to protecting the rights of the most marginalized members of communities) and to protect against potential negative impacts, such as large-scale land transactions without local involvement.

There is a strengthening global trend towards improved governance of land tenure, as reflected in the adoption and dissemination of the United Nations’ Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (VGGT). It is critical that Afghanistan develops an effective and transparent land, governance, administration and management system with the capacity to respond to all users’ needs in ways that provide a stable, secure, land and property rights system for citizens and potential investors in ways that preserve and protect the country’s natural resources.

Key Issues and Intervention Contraints

The international community continues to reaffirm its support to the Government of Afghanistan. At the NATO Warsaw Summit in July 2016, development partners pledged 4.5 billion USD per year in security grants for the next four years, while at the Brussels Conference on Afghanistan in October 2016, the international community pledged 3.8 billion USD per year in civilian donor grants for the same period. The sustained high levels of support indicate broad confidence amongst the international community in Afghanistan’s development prospects and in the significant progress the Government has made towards achieving reforms. At the same time, the goals of land policy, findings from the recently completed Land Governance Assessment Framework (LGAF), and substantial efforts by the country’s leading independent land authority, ARAZI, indicate several actionable steps to advance a stable land rights system in Afghanistan.

Most of the pledges of the National Land Policy of 2007 have not yet been “absorbed” into the legal framework of the country. The Land Policy, while developed in a semi-participatory manner (only among public institutions), has been left without a matching legal framework to support it and therefore remains more as an aspirational reference document. Additionally, customary law, which represents most of the country’s land holders and users, remains poorly integrated with formal law and policy. A whole section in the National Land Policy is also dedicated to environmental sustainability, but again lacks corresponding laws to ensure proper implementation and contains no provisions for public monitoring.

Further development of the legal framework should also support the 2017 amendments to the 2008 Law on Managing Land Affairs that: support informal dispute resolution, an important avenue for resolution especially among the poor who may not be able to afford to resolve problems in court; set aside protected areas as unavailable for lease; remove legal impediments created or permitted on the basis of gender, language, religion or marital status; and serve diverse land interests of society such as farm tenants, sharecroppers, workers, pastoralists and urban residents.

Customary law is only partially recognized in the current legal framework for land. Additionally, an estimated 80 percent of households have no formal documentation to acquire or prove their rights, and thus no protection of those rights by statutory law. This is also true in the case for collectively held lands, public lands and for lands used by Kuchi nomadic tribes. Insecure property rights are a critical underpinning of widespread land grabbing and usurpation. Further, although a number of the new provisions of the 2008 Law on Managing Land Affairs (LML) drafted in 2017 are well intentioned, in both substance and process they may fail to deliver on recognition of customary law. Both ARAZI and the findings of the LGAF call for continued evolution of land law that widens the scope of customary land tenure recognition to include these groups. Examples include supporting development and implementation of the draft Restitution Policy on Land Grabbing and the Customary Deed Registration Law, drafted by the Judicial Reform Commission in 2005, which stipulates the possibilities of formalization of non-documentary land ownership evidence. Proposed amendments to the LML by ARAZI also introduce a new type of land called “Special Village Land.” This proposed classification might ameliorate some of the challenges of the existing state/private land conflicts that, in essence, deny rights to community ownership. Also, by providing simple legal guidance and technical support as to how a community can voluntarily carry out fully inclusive community-based identification, adjudication and recording of all rights affecting its village or neighborhood area, a community can begin a first step toward identifying and eventually recording de facto tenure arrangements to inform further land law and administration initiatives.

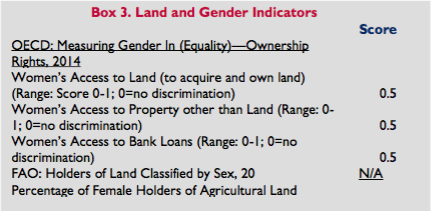

Numerous studies indicate that almost all land is registered in the name of the male head of household and that less than 2 percent of women own land, and most of those women are widows. The reasons for low rates of land ownership include strong social and customary barriers to property ownership by women, where patriarchal structures remain prevalent. Additionally, existing land laws have been inconsistent on the issue of discrimination against women and girls. Where law is helpful in determining land ownership, as in the case of the Constitution and Shari’a law, women and girls are often left without sufficient protection and assistance to realize their land rights. Women also have extremely limited access to both state and non-state dispute resolution fora, again because of strong and strictly enforced social norms. ARAZI has begun to remedy the practical and institutional obstacles to recognize and mitigate the official and hidden costs or registering land by way of issuance of Certificates of Occupancy that can now include up to three wives. Further progress is needed to: strengthen legal aid by hosting legal aid centers; raise awareness on the existing land laws helpful to women; decreasing logistical obstacles (allow geographical jurisdiction transfer) to registration; promote land registration in all spouses’ names; expand statutory justice coverage (mobile courts/admin units); and provide appropriate mechanisms to encourage women to approach formal and informal justice systems while sensitizing the rest of the community about the rights of women to equal access to land.

More than 85 percent of the Afghan population lives in rural areas. Eighty percent of the country’s workforce is within an agricultural sector that comprises 60 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP). Forests provide essential livelihood options and climate mitigation functions, while the untapped mineral resources of the country have been estimated to run as high as one trillion dollars. The Afghan population, and the country as a whole, is decidedly dependent upon land and natural resources. However, further growth and investments should protect the resource access of the poor, prevent land grabbing and balance the interests of investors and small landholders. Both the Government and ARAZI have implemented initiatives to ensure land tenure security for all land rights, whether for individuals or private sector development, with the goal of a centralized system at ARAZI as one-stop-shop for land registration. As an interim measure, community-based land recording systems, which can be connected to ARAZI at a later time, may be a prudent and incremental approach. This can be done through the Community-Based Land Adjudication and Registration, or CBLAR, process. Other efforts can support opportunities for tenure individualization, to include: recognition and recordation of rights; prevention of illegal land transactions; land grabbing; or illegal expropriation.

The Government of Afghanistan has indicated that there is insufficient information about the volume, value and location of Afghanistan’s mines. This complicates the bidding processes, encourages rampant speculation and makes royalty payments a matter of guesswork. The lack of a comprehensive regulatory scheme renders people, communities and the environment vulnerable to corruption and degradation. The weak policies currently in place do little to shield communities from the adverse effects of mining, especially since no matter who owns land, all subsurface resources are owned by the State. The Ministry of Mines and Petroleum (MoMP) lacks the trained personnel to execute its mandate and its efforts to improve this situation are inadequate. Nor does MoMP have the capacity to shut down illegal operations in most parts of the country. The government seeks to improve the stability of the sector through good governance that: confirms the precise size and potential exploitability; develops a strategic long-term vision, including knowledge driven development of the mining sector; more mineral processing within Afghanistan; integration with other sectors of the economy; revised and expanded legislation; a decentralized licensing system, continued efforts to share procurement information in the tender process, due diligence; and mechanisms for revenue and tax collection; environmental review; and an involved and educated civil society.

Natural resources—land, water, forests and mineral deposits—are critical to the country’s prospects for a stable, peaceful and more economically viable future. An estimated 80 per cent of Afghans rely on agriculture, animal husbandry and artisanal mining for their daily survival. Because of the central role of these resources, any pressures that compromise access to or use of land can generate high demand, leading to potential conflicts over them. Climate change, conflict, population migrations, water scarcity and unclear land management, tenure and governance represent some of these challenges and are the source of numerous fracture lines in Afghanistan and the wider region. In Afghanistan, natural resources play a variety of roles in conflicts and at different scales, locations and intensities. The Government of Afghanistan has implemented a number of policies to address climate change, improve land tenure and address water scarcity, but requires support to implement best practice NRM structures, processes and laws in ways that: are contextually appropriate; facilitate and encourage public participation in NRM decision-making, long-term planning and implementation; encourage better data collection; and provide warnings to identify existing and potential disputes over natural resources.

Insecure land tenure lies at the heart of many of the country’s conflicts. Arbitrary eviction, urban informality, internal displacement and accompanying insecurity, ethnically based land use conflicts over water and pastures, illicit poppy production, natural resources exploitation (especially forests and minerals), land grabbing, and food insecurity all compromise the security of individuals and communities. Moreover, violent disputes and clashes involving housing, land and property are both a fundamental cause of localized conflict and a perpetuation of weak land tenure, creating a perpetuating cycle of violence and tenure insecurity. Facilitating true tenure security will depend upon: understanding the specific tenure arrangements in varying geographical contexts; establishing clarity and recognition to the range of land rights and de facto needs for secure land tenure; developing solutions that are reasonable for the uses to which land tenure will be put; and protecting against arbitrary curtailment of land rights.

Summary

Afghanistan is a country under pressure. Fourteen million Afghans, nearly half the population, are extremely poor or vulnerable to extreme poverty. More than 80 percent of the population and nearly 90 percent of the poor live in rural areas, and agriculture plays an important role in their livelihoods. The country’s farmland, pastures, forests and water resources have suffered from successive years of extreme drought and extended conflict. Poppy production is on the rise. Cities have expanded rapidly over the past decade without effective spatial plans and with limited access to formal land and housing. The result has been informal, low-density sprawl, increasing socio-spatial inequality and significant infrastructure deficiencies. Approximately one-third of Afghans live in five city regions: Kabul, Jalalabad, Mazar-i-Sharif, Herat and Khandahar, as well as 28 strategic district municipalities, making these regions crucial for social, economic and territorial transformation. More than half of the returning refugees are unable to return to their place of origin because they have no land or their land has been taken in their absence. In many areas, displacement and disintegration now characterize a society that had historically been defined by networks of reciprocity that guaranteed individual security and social support. Widows, female-headed households and nomadic communities are the most vulnerable.

Development of a legal, land administration and institutional framework to secure and enhance tenure security has been underway over the past 15 years. While statutory laws and institutions seek to improve state land rights, support for private and customary land rights is less robust in formal law. Islamic law (Shari’a) and customary law dominate land relations in Afghanistan; the Civil Code recognizes the application of customary law with regard to land rights. Further legal reforms are required to harmonize law with the 2007 National Land Policy, provide for increased land tenure, identify the varying types of land holdings and tenure arrangements, address land grabbing and support land management at the local levels. Amendments to the Law on Managing Land Affairs have been proposed and include provisions to fight corruption and enable inclusion of customary documents as proof of ownership. These efforts are, to a degree, hampered by a tenure system that is complex and opaque, and the long period of war and political instability has further complicated the land tenure system. Land rights for Afghan citizens in both urban and rural areas remain insecure, especially for women despite helpful Shari’a law and the country’s Constitution, especially as regards inheritance and more formalized land rights respectively. The structural issues underpinning women’s lack of land access and land tenure insecurity include: illiteracy; low female employment; a weak and ineffective judicial system to enforce land laws; absence of awareness of laws; lack of physical access to legal documents; and prohibitive law enforcement mechanisms.

Development of a legal, land administration and institutional framework to secure and enhance tenure security has been underway over the past 15 years. While statutory laws and institutions seek to improve state land rights, support for private and customary land rights is less robust in formal law. Islamic law (Shari’a) and customary law dominate land relations in Afghanistan; the Civil Code recognizes the application of customary law with regard to land rights. Further legal reforms are required to harmonize law with the 2007 National Land Policy, provide for increased land tenure, identify the varying types of land holdings and tenure arrangements, address land grabbing and support land management at the local levels. Amendments to the Law on Managing Land Affairs have been proposed and include provisions to fight corruption and enable inclusion of customary documents as proof of ownership. These efforts are, to a degree, hampered by a tenure system that is complex and opaque, and the long period of war and political instability has further complicated the land tenure system. Land rights for Afghan citizens in both urban and rural areas remain insecure, especially for women despite helpful Shari’a law and the country’s Constitution, especially as regards inheritance and more formalized land rights respectively. The structural issues underpinning women’s lack of land access and land tenure insecurity include: illiteracy; low female employment; a weak and ineffective judicial system to enforce land laws; absence of awareness of laws; lack of physical access to legal documents; and prohibitive law enforcement mechanisms.

Land administration in Afghanistan is complex, involving many formal (statutory) institutions and governance structures, as well a variety of informal (non-statutory) institutions especially those that are involved in the resolution of land issues and disputes. In general, the current institutional framework for land management and administration is not considered inclusive or pro-poor, despite some government efforts. Outdated systems, overlapping responsibilities, lack of capacity at local levels, conflicting systems for land ownership and uncertain or incomplete legal frameworks, compounded by decades of conflict and widespread displacement have resulted in competing claims to land. ARAZI, the country’s leading independent land authority, is tasked with maintaining records with respect to all land, both public and state, including maps, surveys, ownership records and land transactions and has been working earnestly to improve land administration. Despite these legal and policy advances, serious practical challenges remain to administering and managing land in Afghanistan. Land grabbing, or “land usurpation,” and concomitant informal development in both the urban and rural sectors by returnees, armed actors and powerful elites, remain largely unaddressed. Returnees from neighboring countries continue, with more than half a million crossing from Pakistan alone in 2016, after decades out of the country. However protracted conflict, extended periods of drought and deterioration of the rural economy have undermined Afghanistan’s historically strong centralized institutions and allowed for the rise of regional power structures, some of which are extra-legal.

Legal and land administration institutions lack both the capacity and the authority to manage land and natural resources. For example, the country has ample water resources if effectively conserved, but the capacity to store, use and manage them is weak. However, the Government has taken important steps in improving water management. It has acknowledged that access to water is a right of the people and the Afghanistan National Development Strategy (ANDS) identifies water infrastructure as one of the key priorities. Afghanistan’s forests are seriously threatened despite their essential use for households for wood for fuel and construction, land for cultivation and grazing livestock and forest products such as nuts, tubers, fodder and fibers. Timber is in high demand on the international market and in neighboring Pakistan. Although commercial timber harvesting is illegal in Afghanistan, a systematic smuggling industry exists. Uncontrolled logging, urban encroachment and ineffective forest management have decimated Afghanistan’s forests. Tree coverage declined by almost 3 percent per year between 2000 and 2005. If current trends continue, all forests are likely to disappear in the next 30 years. The implications for deforestation and severe climate change are grave; drought is likely to be regarded as the norm by 2030, rather than as a temporary or cyclical event. Whereas water and forests are scarce resources, Afghanistan has abundant mineral resources, though most have not been successfully explored or developed.

At least 24 potentially world-class mineral deposits have been identified as “Areas of Interest,” which represent both the mineral and its geographic location. The Afghan Ministry of Mines and Petroleum (MoMP) has indicated that the annual income through mining could reach as high as 3.5 billion USD, covering 77 percent of the total core budget of the Afghan government. Despite the potential in the sector, it remains undeveloped due to poor access, lack of energy and water, which is needed in mining operations, weak governance and insecurity. The government has sought to sustainably exploit its mineral resources and became a candidate for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in 2009.

In much of the country, local elites, warlords and political factions control land and natural resources through a combination of physical force and customary legal regimes that reflect deeply entrenched power structures. Afghanistan’s population faces constraints on access to land, insecurity of tenure and the depletion of natural resources. The resurgence of the Taliban, continued conflict and growth of the opium poppy industry have created barriers to development. In many cases, reconstruction and development are taking place in a conflict-management context as opposed to a post-conflict setting.

Afghans have been enduring the adverse consequences of forced displacement for decades, with Afghanistan having the largest number of its people living as refugees in protracted exile of any country in the world. It is estimated that 2.5 million registered Afghan refugees remain in neighboring countries, with possibly an equal number of undocumented migrants with similar protection needs in Iran and Pakistan. Internal displacement is also significant problem, with an estimated 1.2 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) in need of humanitarian assistance. The return of displaced people has been unevenly spread in terms of time and location, creating disproportionately large challenges to the absorption capacities of some districts and provinces. While the local impact of a massive influx of refugees on particular areas and their capacity to reintegrate these refugees depends on a range of factors, there is a real risk that shocks resulting from the influx have increased competition for resources or exacerbated pre-existing causes of conflict.

Land

LAND USE

There are 65 million hectares of land in Afghanistan, of which: 7.8 million hectares are agriculture lands; 30 million hectares are pastures; 8 million hectares are desert; 1.9 million hectares are forests; and 17.5 million hectares are mountains, rivers shores and rocky areas. According to ARAZI, less than 30 percent of properties in urban areas and 10 percent of properties in rural areas have been registered by official institutions of the state. More than 80 percent of the population and nearly 90 percent of the poor live in rural areas, and agriculture plays an important role in their livelihoods. Uses within agricultural lands are spatially diverse, ranging from intensive irrigated crop systems, in which farmers practice multiple cropping, to extensive livestock systems in dryland areas, to illicit opium poppy production. Opium production remains a significant feature of agricultural land use. The total area under opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan was estimated at 201,000 hectares in 2016, a 10 percent increase from the previous year. Strong increases were observed in the Northern region and in Badghis province where the security situation has deteriorated since 2015. Ninety-three percent of opium poppy cultivation takes place in the Southern, Eastern and Western regions of the country (ARAZI 2014; World Bank 2014; UNODC 2016).

Kabul houses approximately 41 percent of the urban population. Kabul and the four regional hubs of Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif, Kandahar and Jalalabad are home to 69 percent of the total urban population. Cities have expanded rapidly over the past decade without effective spatial plans and limited access to formal land and housing. The result has been: informal, low-density sprawl; increasing socio-spatial inequality; and significant infrastructure deficiencies. Many of Afghanistan’s urban challenges have a clear land use dimension, including land grabbing, inefficient use of land, tenure insecurity in informal settlements (70 percent of dwelling stock), limited access to well-located land for housing by middle- and low-income households, insufficient land for economic activity and undeveloped land-based financing for local service delivery (GIRoA 2015b; GIRoA 2014b; Popal 2014).

In both rural and urban areas, over twenty years of civil conflict have left Afghanistan heavily contaminated with land mines and unexploded ordinances (UXO’s). A 2012 study by the Mine Action Coordination Center of Afghanistan further estimates that there are 5,489 hazardous areas remaining in Afghanistan, affecting 563 sq. km and 1,847 communities (MACCA 2012; GICHD 2012).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Afghanistan’s total land area is about 652,090 square kilometers. The population is estimated at 34 million people. Of the 78 percent of the population that lives in rural areas, roughly 20 percent are classified as nomadic. Agricultural land accounts for 58 percent of the total land area, but only 12 percent is useable farmland, with the balance pasture land, which supports the country’s large nomadic and semi- nomadic population and its livestock. Forests make up 1.3 percent of the country’s total land area. Deforestation is occurring at a rate of 3 percent per year. Roughly 0.3 percent of the total land area is designated as protected.

Afghanistan has more than 40 ethnic groups, the largest of which is the Pashtun (53 percent of the population), generally residing in the eastern and southern regions. The Tajiks in the northeast (17 percent) and Turkic groups in the northern plains (20 percent) are the second- and third-largest groups (ADB 2014; World Bank 2014).

Unequal land distribution has a deep history; successive governments in Afghanistan have adopted land allocation policies as a means of rewarding patrons and consolidating power. Recent efforts to address continued inequities in landholdings began in 1978 when the communist government initiated new land reforms that reduced the ceiling for land holdings, allowed the state to seize excess land without paying compensation and provided for free distribution of land to landless and poor households. Decades later, to counter the continued widespread distribution of public lands the Government issued Decree 99 in April 2002 to freeze distribution of public land. Despite these efforts, land continues to be illegally occupied or controlled by powerful interests (Gebremedhin 2007).

Distribution of land holdings in the agricultural sector, which accounts for 90 percent of the country’s manufacturing vis à vis agro-processing, employs 60 percent of the total Afghan workforce, and generates 25 percent of GDP, is especially problematic. Sixty percent of agricultural holdings are less than one hectare and represent 22 percent of croplands meaning that land fragmentation has implications for both demand for land for agricultural expansion and the risk of lower land ceilings for those who rely on land for food security and livelihoods (Alden Wiley 2003; Gebremedhin 2007; Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund 2017).

Approximately one-third of Afghans live in five city regions: Kabul, Jalalabad, Mazar-i-Sharif, Herat and Khandahar, as well as 28 strategic district municipalities, making these regions crucial for social, economic and territorial transformation. On average, 46 percent of total land area within the city regions is agricultural land, of which approximately 81 percent is irrigated for agriculture, reaffirming the relatively stable and central role of agriculture in these regions. Industrial land use comprises only 3 percent of built-up area. Within built-up areas, 40 percent of this land is residential. Most residential areas are irregular or informal housing developments. Socio-spatial exclusion and inequality are pervasive in all city regions. Living conditions are poor and those who are internally displaced are not integrated within the cities. For example, in the Herat city region, over 25,000 people are living in protracted displacement situations, without formal recognition of land or housing rights, despite the fact there is sufficient land, which is estimated to total more than 66,000 hectares of land within the five city regions (GIRoA 2016b; UNAMA 2015; World Bank 2017).

During the past 15 years more than five million Afghan refugees have returned to their country, to both urban and rural areas. Most of the repatriates have not been able to return to their own homes due to insecurity. The government of Afghanistan has built townships in, for example, the eastern Nangarhar and Herat provinces and has provided ownership documents of residential plots to tens of thousands of returnees. However, many returnees assert that they have not yet received their designated land plots and the government-built townships lack essential services. Land usurpation, or land grabbing, by powerful individuals in these townships is widespread. Reports of land allocations to political and economic elites suggest that state land distribution in Afghanistan continues to be employed to reward patronage, solidify political loyalty and exercise and control power (GIRoA 2012c; LandAc 2016; Barshodost et al 2017).

It is important to note the de facto land distribution that has occurred in the country. The chaotic political scenarios of the 1990s dominated by the mujaheddin and Taliban led many wealthier farmers to leave their lands during the various episodes of the war, trusting their land to relatives or simply abandoning it. Individual militia commanders have accumulated lands informally in a context of lawlessness prevailing in many parts of the country right after the demise of the Taliban. Finally, swift accumulation of wealth through poppy cultivation and opium trade is believed have led to some re- concentration of lands (Maletta 2007).

The objective of current state land distribution efforts is to ensure sufficient and fair designation and distribution of state lands for infrastructure, state revenue-producing projects, agriculture and commercial activities, residential needs in urban areas and humanitarian requirements for adequate shelter including vulnerable populations such as IDPs and returnees. A combination of weak legislation, ill-considered resettlement schemes, strong ethnic and tribal ties and de facto enduring systems of customary tenure have limited distribution reforms’ intended impact. Specifically, a lack of overarching and integrated national policy on state land distribution, a lack of transparency and oversight by the institutions and government officials involved in land distribution, ineffective subnational governance, and limited desirable land (i.e., land that is fertile proximate to roads, infrastructure and economic opportunity) in urban, peri-urban areas, has constrained legitimate state efforts (Gaston and Dang 2015; UNAMA 2015; World Bank 2016b).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Afghanistan Constitution, passed in 2004, authorizes personal land ownership (except by foreigners) and protects land from state seizure unless the seizure is to secure a public interest and the owner is provided with prior and just compensation. In addition, the Constitution mandates land and housing distributions under certain conditions. The Law on Managing Land Affairs (LML) of 2008 sets forth the basic framework for land administration and management in Afghanistan. The LML sets out definitions for various land types and classifications, requirements for land deeds and principles governing: allocations of state land; land leasing; land expropriation; settlement of land rights and restoration of lands; pastureland management; and civil and criminal penalties for land usurpation. The law recognizes Shari’a and defers to applicable principles of Shari’a in some areas. Issues that are not covered by the LML are governed by the country’s Civil Code, which in large measure reflects the Hanafi school of Shari’a. Customary law dominates land relations in Afghanistan and the Civil Code recognizes the application of customary law with regard to land rights. Customary law is in large measure consistent with Shari’a, and Shari’a permits the practice of customary law so long as it does not interfere with tenets of Islam. Customary law systems vary but share the following characteristics: use of customary village councils (known in Dari as shura, or jirga in Pashtu) that employ mediation and arbitration techniques of dispute resolution; the application of principles of apology and forgiveness; and the concept of restorative justice (GIRoA 2004; GIRoA 2008; GIRoA 1977).

In urban areas, the Municipality Law of 2000 contains provisions applicable to regulating and governing land within municipalities. ARAZI has responsibility for urban land management and administration by as set forth in the provisions of the LML (UN Habitat 2015; GIRoA 2000b).

While statutory laws and institutions seek to secure state land rights, support for private and customary land ownership rights is less robust in formal law. The current land framework fails to sufficiently address and balance private ownership rights with the state’s need to obtain and access land for infrastructure and revenue-producing projects, such as mining. Expert reports have discussed the need to reform the LML to reflect the vision and mandate establishment of the newly independent ARAZI, harmonize law with the 2007 National Land Policy, provide for increased land tenure, identify the varying types of land holdings and tenure arrangements, address land grabbing and support land management at the local levels. Amendments to the LML have been proposed and include: provisions to fight corruption; inclusion of customary documents as proof of ownership, which can then be treated as formal land ownership; and streamlined land leasing processes (UNAMA 2014; Alden Wiley 2012; ARAZI 2012).

TENURE TYPES

There are three categories of land with accompanying methods to transfer. These include:

- Private Land—Land individually held without title, with a non-recognized title or with state formal title, as well as collectively held land without or with customary title or with documentation issued by previous government regimes. Transfer of private land can occur through sale, inheritance or compulsory land acquisition.

- Public Land—These lands include pastures (allocated for public use), forests, graveyards, roads, green areas, playgrounds; schools, universities, and hospitals. Public land is essentially state-owned land with a purpose designated by government Ministries or municipalities. These lands cannot be sold, leased, transferred or exchanged without a compelling case for reuse or repurpose.

- State Land—Includes forests, protected land, arid and virgin land (registered as state land and any land that is deemed public but is not registered in the book of government lands). Only arid and virgin land can be leased or sold provided certain conditions (Land Act 2016).

Afghanistan’s land is vested: (1) individually in private individuals and entities; (2) communally in families, clans and communities; and (3) in the government and has the following tenure types:

Ownership. Ownership is the most common tenure type in Afghanistan. Ownership may be based on formal or customary law and ownership rights can extend to all land classifications. Ownership confers a right of exclusive possession of land and owners are entitled to use and dispose of land freely. Under the 2008 Law on Managing Land Affairs, all land not proved to be private is deemed to be state land (GIRoA 2008).

Leasehold. The 2008 Law on Managing Land Affairs permits leasing between private parties, subject to requirements for written leases that describe the land and set forth the agreement of the parties regarding the length of the lease and payment terms. For purposes of attracting investment, the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock (MAIL) can lease agricultural land to individuals and entities for purposes of agricultural activities for periods up to 50 years for fertile land and 90 years for virgin and arid (i.e., uncultivated) land. The MAIL can lease virgin and arid land for non-agricultural investment purposes with the agreement of other departments and consistent with considerations of land type and proportion. Other ministries and departments can lease land for non-investment purposes for periods up to five years. Leases of private land, which have primarily been governed by customary law, are generally quite brief, often extending only a season. Sharecropping is a common arrangement: the landowner contracts with the sharecropper to cultivate the land, with the parties agreeing to terms regarding the production shares and payment for inputs (GIRoA 2008; UN Habitat 2017).

Agreed Rights of Access. The 2008 Law on Managing Land Affairs provides that pasture land is public property that neither the state nor any individual can possess (except as otherwise provided by Shari’a), and which must be kept unoccupied for public use for activities such as grazing and threshing grounds. Customary law provides that individuals and communities can obtain exclusive or non-exclusive rights of access to government-owned pasture land through customary use and deeds (GIRoA 2008b; UN Habitat 2017).

Occupancy Rights. In urban areas, landholders in formal settlements generally have formal rights to the land. Occupants of informal settlements, including squatters, usually have some type of informal rights that are based on principles of customary law, the nature of the land and the means by which the occupants took possession of the land. The 2007 Land Policy permits the regularization of rights from informal settlement holdings but implementing legislation has yet to be enacted (GIRoA 2007).

Mortgage. Formal and customary law recognize two types of land mortgage: one type operates as a debt secured by the land. The second type, which is the most common, is a use mortgage under which the lender takes possession of the land until the borrower repays the debt (UN Habitat 2017).

It is important to note that despite the relatively straightforward tenure types presented above, land ownership and land access rights in Afghanistan are very complex and opaque, and the long period of war and political instability has further complicated the land tenure system. At any given time, for example, a single farmer may be owner, tenant or sharecropper and may be in transition from one status to another with respect to one or more of his plots (UN Habitat 2017; Alden Wiley 2003).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Land rights for Afghan citizens in both urban and rural areas are insecure. Afghanistan’s land is vested: (1) individually in private individuals and entities; (2) communally in families, clans; (3) in communities, for example pastures; and (4) in the government. Land ownership can be acquired through purchase, government land allocation and other forms of transfer of ownership, such as through inheritance. Under current law, all untitled land is characterized as state land unless a person can show ownership through a legally valid deed, which is the basic unit of registration evidencing the transaction in land. Registration is a judicial function in which primary court judges have responsibility to draft and archive legal deeds and ARAZI certifies the identity of the parties. Acquiring and registering a deed is costly and difficult. Additionally, a title or registration of title is no guarantee of establishing ownership and obtaining land rights. Title deeds may be registered with numerous institutions at several locations, creating significant opportunities for fraud and corruption with multiple titles being registered at different locations for the same or overlapping areas of land (GIRoA 2008; LandAc 2015; UNAMA 2014).

Most people, then, acquire rural land through inheritance transfers, with no documents or records to establish ownership of the land they are occupying. Nomadic or semi-nomadic people may acquire pasture lands for grazing their livestock through application to the local authorities stating the need for land and through the identification of vacant land (mawat). Individuals can apply for ownership rights to mawat land by demonstrating that the land has not been not cultivated, improved or is under ownership, and that they will agree to either cultivate or improve the land. These practical solutions to owning and accessing rural land completely bypass the formal land system, resulting in an informal shadow land economy. As a result, the majority of those occupying land in Afghanistan are legally “landless.” Private land disputes are generally put forward to a shura or jirga for resolution. In rural areas the key drivers of continued land insecurity are: (1) a history of inequitable relations within communities with regard to access and rights to land and water; (2) multiple unresolved interests over the same land, including rights of nomads; (3) failure to develop accepted principles governing holdings of non-agricultural land; and (4) continuing violence and disorder, uncontrolled poppy production, warlordism, land invasions and ethnic disputes (GIRoA 2008; UNAMA 2014).

In urban areas, most people acquire land through purchase, lease or squatting. Settlers on unplanned urban lands typically have customary deeds or occupancy rights, some of which have been regularized or benefit from the “blind eye” of the government (World Bank 2005).

Shari’a law is the strongest acknowledgment of the land and tenure rights of women by way of its guidance regarding inheritance for wives and daughters. Still, women face significant impediments to asserting their land rights to mahr (dowry) or those acquired through inheritance because of cultural norms and the lack of access to either the formal or informal systems. In urban settings, female heads of household and widows are, anecdotally, increasingly asserting their rights to land, but they are unlikely to try to register their rights formally because the process is time consuming and costly (UN Woman 2011).

In both urban and rural areas, criticism of the Law on Managing Land Affairs of 2008 asserts that it fails to protect customary land tenure because of its unrealistic and often unattainable requirements that rely on documents to establish legal ownership and convert such documents into a formal deed (GIRoA 2008; UNAMA 2014).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Women’s rights to land must be considered within the context of women’s rights in Afghanistan as a whole, which are among some of the worst in the world and include: attacks on women in public life; violence against women; child and forced marriage; lack of access to justice; and lack of girls’ access to education. Women’s land ownership in Afghanistan has two diverging dimensions: (1) The legal guarantees to rights of ownership; and (2) the de facto access to land and accompanying rights.

Women’s rights to land must be considered within the context of women’s rights in Afghanistan as a whole, which are among some of the worst in the world and include: attacks on women in public life; violence against women; child and forced marriage; lack of access to justice; and lack of girls’ access to education. Women’s land ownership in Afghanistan has two diverging dimensions: (1) The legal guarantees to rights of ownership; and (2) the de facto access to land and accompanying rights.

On paper, women in Afghanistan enjoy rights to land. The Constitution provides that women cannot be precluded from owning or acquiring property. Article 40 also states that property is immune from invasion, that no person shall be forbidden from acquiring and making use of a property except within the limits of law, and that no one’s property shall be confiscated without the provisions of law and the order of an authorized court. The Afghan Civil Code recognizes a woman’s right to own and sell property. A woman can sell her property out of her own free will and she can donate it if she chooses to do so. A woman may obtain property through marriage, inheritance or purchase with her own income. The Civil Code also defines the inheritance rights of women and girls with respect to the Islamic Shari’a. Islamic Law recognizes and protects three kinds of property: the first is acquired through either inheritance or labor; the second, directs compliance with the women’s rights as articulated under the law; and the third outlines the women’s ownership of property, including land. Islamic law grants widows one-eighth of the property of the deceased spouse, and daughters inherit half the share of land inherited by sons (Human Rights Watch 2017; GIRoA 2004; GIRoA 1977).

Despite these formal provisions and customary provisions, de facto realization of ownership rights is limiting women’s access to their legal right to property. Daughters tend to relinquish their inherited land rights to their brothers, especially at marriage, because their husbands are the main providers of the family. Widows who inherit land commonly transfer it to their sons. In the rare cases where women do retain control of inherited land, it is usually because they have no brothers and are not married, and thus must keep the land to support themselves. The structural issues underpinning lack of land access and land tenure insecurity include: illiteracy; low female employment; a weak and ineffective judicial system to enforce helpful land laws; absence of awareness of laws; lack of physical access to legal documents; and prohibitive law enforcement mechanisms (Akbar and Pirzhad 2011; ECW 2014).

However, in 2016 as part of a new initiative to increase security of tenure in Kabul, ARAZI, with donor support from USAID and technical support from UN Habitat, developed a program to gradually upgrade land and property rights of urban households through the issuance of occupancy certificates. For the first time, occupancy certificates have been issued to women only, and women as joint owners along with their spouses, in order to recognize and regularize the various forms of tenure that exist outside the formal register among urban poor communities, including in informal settlements, in Kabul city (UN Habitat 2016).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Land administration in Afghanistan is complex, involving many formal (statutory) institutions and governance structures, as well a variety of informal (non-statutory) institutions especially those that are involved in the resolution of land issues and disputes. The Afghanistan Government has been engaged in land administration, primarily as a means of collecting taxes, since the early 1900s. The institutional structure has changed throughout those hundred plus years. Primary responsibility for land administration now falls with ARAZI. ARAZI is vested with authority in the following specific areas: (1) state-owned land inventory; (2) state land registration through the land rights identification process (Tasfiya); (3) land registration through the cadastral survey process (land survey); (4) land transfers and exchanges, primarily to other government divisions; (5) leasing land to the private sector; and (6) resolving disputes involving state and public lands. In practice, ARAZI keeps records with respect to all land, both public and state, including maps, surveys, ownership records and land transactions, although this process is not yet complete (GIRoA 2008, ARAZI 2014).

ARAZI engages in state land management at the provincial and district levels through Settlement Commissions set up at provincial capitals throughout Afghanistan. The commissions address land ownership issues between individuals and the government and between the government and government entities. In addition, the commissions make recommendations regarding state land distributions to private individuals. Their specific obligations and powers include, among others: settlement of landholding areas; distribution of documents and land; determining the categories, water rights and taxation of land; determining and segregating lands as individual or state, as well as their classification such as grazing, arid, jungle lands; and restoration of previously illegally distributed land to the owner or legal heirs. The Cadastral Survey Office, formerly the independent Office of the General Geodesy and Cartography, merged with ARAZI in 2013 and specifies the territory, map and measurements of a piece of land (GIRoA 2008; UNAMA 2014).

ARAZI does not manage urban land and townships. Municipal land is controlled and managed by local governance officials under the management of the Independent Directorate for Local Governance (IDLG), and the Ministry of Urban Development and Housing (MUDH) is responsible for developing master urban plans and policies and supporting the revenue and capacity building programs of municipalities, including infrastructure and services, sanitation and preservation of historic areas. MUDH issues and updates these plans and is involved in policy and decision making relevant to informal settlements and services within the municipalities (GIRoA 2017).

In terms of dispute resolution, several courts and offices within them are legally responsible for resolving land disputes and issuing, registering and storing titles. The relevant courts include the public rights courts, civil courts, personal status courts and commercial courts. The Office of the Directorates of Documents and Deeds Registration, which encompasses Protected Document Registry and Court Archives, is located within the appellate courts at the provincial level and issues and maintains title deeds. Estimates indicate that over 60 percent of all cases brought to a shura or jirga involve a land dispute. Village councils (shura or jirga) are active in local matters, including land issues and disputes. The shura system is sometimes criticized as representing the majority political factions and elites at the expense of economically disadvantaged and vulnerable groups. Women are not permitted to be members of the shura (GIRoA 2011; Dempsey and Coburn 2010; Coburn 2011).

In general, the current institutional framework for land management and administration is not considered inclusive or pro-poor, despite government efforts. Outdated systems, overlapping responsibilities, lack of capacity at local levels, conflicting systems for land ownership and uncertain or incomplete legal frameworks, compounded by decades of conflict and widespread displacement have resulted result in competing claims to land and conflicts between individuals, among communities and between citizens and the state (Unger et al 2016; World Bank 2016).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Urban-based economic activity now accounts for over 50 percent of GDP in Afghanistan, yet the urbanization process has been largely informal. It is estimated that 70 percent of urban property is unregistered. Still, the land market is a key source of municipal revenues. Sale of municipal land and properties is the largest revenue source, contributing an average of 22 percent of total annual revenues in Kabul and 19 percent in thirty-three cities throughout the country. Land leases account for an average of 13 percent of revenues, followed by seven percent for property leases. The process for selling land was streamlined by the government in 2009 to encourage formal registration of land transactions. The number of steps required was reduced, as were the taxes due at the time of sale. While these changes improve and simplify the conveyance process, and some increase has been seen in the number of transactions, registered titles can be subject to attack by others claiming superior rights in land. Anecdotally many land sales occur informally, making land transactions highly vulnerable to corruption and constraining legitimate development opportunities in the future for municipalities. At the same time there is sufficient land to accommodate housing and development. Municipalities possess on average 27 percent vacant plots (land subdivided but not yet occupied) in built up areas, reflecting land sales by municipalities and private sector speculation. These vacant plots are sufficient to accommodate another 4 million people at current densities, adequate for urban growth in the coming 10 years (EMG 2010; GIHCD 2012; GIRoA 2015b).

The rural land market is constrained by a dearth of arable land, insecurity, land disputes, landmines left from wars and infighting and limited irrigated land. Most land is transacted by informal deeds, relying on oral history and community knowledge for identification and using witnesses for authentication of identity and enforceability of rights (Shirzai 2016).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Under Article 40 of the Constitution, the government may take private property if: (1) it is “for the sake of public interests”; (2) the government provides the owner with “prior and just compensation”; and (3) the government obtains an order from an “authoritative court.” The Law on Land Expropriation of 2000 (amended in 2005 and 2010), administered through the Council of Ministers, recognizes private property and provides for acquisition of private land for public purposes. Public purposes may include but are not limited to: construction of manufacturing institutions; highways; railways; pipelines; extension of communication lines; power transmission cables; sewerage canalization; water supply network; religious mosques and schools; implementation of urban plans and other public welfare entities; mining and extraction from underground reservoirs; lands with cultural or scientific importance; cultivatable lands, vast gardens and major vineyards that have economic importance; and lands [planned] for dams. Other lands may be expropriated in exceptional circumstances upon the approval of the Council of Ministers. The Law states that expropriation should be done with great care and by the competent authorities and compensation for all other assets e.g., structures, crops, trees etc., on the land should be paid based on market rate. But the law does not specifically provide for resettlement and rehabilitation including provision of additional assistance to eligible affected families, restoration of business/income loss or other assistance/rehabilitation measures (GIRoA 2004; GIRoA 1977; GIRoA 2000; Gaston and Dang 2015).

The 2008 Law on Managing Land Affairs relates to expropriation in that it addresses how private property is defined, how private properties are identified and formalized, how the government may lease lands to investors or allocate it to landless persons and how state power over land holding is vested. Compulsory acquisition is covered in Articles 21-22 of Chapter Three and reinforces that the right to buy private land for a public purpose is a normal state right (UNAMA 2014; GIRoA 2008; ADB 2014).

Because customary ownership and long-standing communal ownership or usage rights are not recognized in expropriation law, vulnerable groups in rural and urban areas, especially the landless or those living in informal developments, are not protected through any compensatory mechanisms under formal law. Proposed revisions to the Law on Managing Land Affairs and Law on Land Expropriation will broaden the power and scope of ARAZI to tighten and limit the definition of what constitutes public purpose, which are not provided in either of the laws’ revisions. Current proposed revisions to the law include accepting customary documents as ownership documents. The Law on Land Expropriation proposes provisions for just, fair and market value compensation, public consultation and public hearings. Land advocacy groups call for any revisions to laws relating to expropriation to be more explicitly pro-poor (Wiley, 2012; ARAZI 2012; ARAZI 2014).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The Government of Afghanistan recognizes that the development and stability of the country depend to a large extent on the efficient use of its land resources, in both rural and urban areas. Since 2001 it has sought, in theory, to implement a system of modern land administration and governance by pursuing: policy, legal and regulatory reform; international good land practices; institutional development; and increased decentralization of land matters to the village level. In terms of policy, the objectives of 2007 National Land Policy are to: provide every Afghan with access to land; promote and ensure a secure land tenure system; encourage the optimal use of land resources; establish an efficient system of land administration; and ensure that land markets are efficient, equitable, environmentally sound and sustainable to improve productivity and alleviate poverty.

The 2008 Law on Managing Land Affairs covers such fundamental subjects as: how private property is defined, identified and formalized in legal ways; how the government may lease lands to investors or allocate it to landless persons; and how state power over land holding is vested. The Law has been criticized for instituting a strong bias towards owners with documentation, despite estimates that up to 90 percent of Afghans have no documentation over their holdings. In an effort to protect the property rights of the vast majority of land owners, holders and users, current proposed amendments to the Law seek to protect private property rights, as opposed to state property rights only, by accepting customary documents as ownership documents. Additionally, proposed changes to the Land Expropriation Law (LEL) of 2005 vis-a-vis the draft Land Acquisition Law, currently under review by the Ministry of Justice: proposes more concrete categories of public projects with examples for each as compared to LEL 2005; proposes a third party monitoring body, which can assess whether the leased and transferred land is used for their destined purposes; and requires the organization developing a public interest project to estimate the least amount of land required for it (ARAZI 2014; ARAZI 2014; Alden Wiley 2012).

In one of the most centralized governance systems in the world, efforts to decentralize land governance and ensure it is responsive to local realties on the ground are, in part, evidenced by the establishment of an independent ARAZI in 2010 to provide a balanced approach between (a) pro-poor land administration services in support of individual and collective tenure security through land registration, and (b) land allocation and the provision of land to support private sector investment in infrastructure, natural resources, agriculture and industry. Most recently, ARAZI has further broadened its scope and authority through application of the Land Governance Assessment Framework (ARAZI 2014; ARAZI 2014b; Alden Wiley 2012; World Bank 2014; Nezam 2017).

Despite these legal and policy advances, serious practical challenges remain to administering and managing land in Afghanistan. Land grabbing, or “land usurpation,” and concomitant informal development in both the urban and rural sectors by returnees, armed actors and powerful elites, remain largely unaddressed. In response, ARAZI has identified 18,000 illegal land grabbers and is developing a plan to return these confiscated lands to their rightful owners. At the same time, returnees from neighboring countries continue, with more than half a million crossing from Pakistan alone after decades out of the country. Due to continued insecurity and land usurpation, many are seeking homes in urban areas, but land speculation has driven land and rent prices out of reach for these vulnerable populations. At least one factor in rural insecurity is an increase in opium production both in terms of areas under cultivation and the geographic spread of growing areas. The total area under opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan has increased by 10 percent in 2016, while less than 14 percent of the country’s provinces were reported to be free of poppy cultivation. While the Karzai government made opium poppy cultivation and trafficking illegal in 2002, many farmers, driven by poverty, continue to cultivate opium poppy to provide for their families. (Nahid and Dowy 2017; Muzhary 2017).

Urban development is also on the governmental agenda presently and in the coming decades, as urbanization has been recognized as one of the most significant drivers of change—and opportunities for change. The Afghanistan National Peace and Development Framework (ANPDF) sets out the overall perspective for the coming five years, including the new emphasis on urban development. The Urban National Priority Program (U-NPP) frames subsequent policies and legislative action required under the ANPDF. The Vision Statement from the U-NPP strives for a network of dynamic, safe, livable urban centers that are hubs of economic growth and arenas of culture and social inclusion through decentralized urban planning and participatory urban governance by 2024. As regards land, the program recognizes that tenure insecurity, land grabbing and usurpation, uncontrolled planning and informality are the norm (GIRoA 2017c; GIRoA 2016c, AREU 2017b).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

Over the past decade the World Bank has provided support in the land sector, the most recent of which has been the completion of The Land Governance Assessment Framework (LGAF) in Afghanistan. The LGAF, developed by the World Bank in partnership with the Food and Agriculture Organization, International Fund for Agricultural Development, International Food Policy Research Institute, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN Habitat), the African Union and numerous bilateral partners, is a diagnostic tool to assess the status of land governance at the country level using a participatory process that systematically draws on existing evidence and local expertise as opposed to the knowledge of outsiders (AREU 2017).

The European Union is funding the Strengthening Afghanistan Institutions’ Capacity for the Assessment of Agriculture Production and Scenario Development project 2017-2020. The project will establish a Land Resources Information Management System to guide policy-makers in developing appropriate policiesand plans for various land uses (especially agriculture) and providing location-specific adaptation options. The project also aims to develop the monitoring and analyzing systems of land resources and to study the proportionate specifications of land against the environmental risks at the local and national levels (United Nations 2017).

Land and dispute resolution has become a focus on recent donor efforts. USAID and the United States Institute for Peace (USIP) Strengthening Peace Building, Conflict Resolution and Governance in Afghanistan Project 2015-2020 was established to support peacebuilding efforts in Afghanistan through policy research, provision of grants to Afghan civil society organizations and technical assistance to strengthen the legitimacy of Afghan government institutions. A component of this project is to work with ARAZI to develop a land registration process and support Afghan government institutions to build dispute resolution mechanisms, including a pilot system to register land disputes resolved through tribal customary law (USAID 2016; Gaston and Dang 2015).

Water

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Agriculture is one of the country’s main economic drivers with estimates that up to 80 percent of its people derive their livelihoods from the sector. Despite its importance, water scarcity and decayed infrastructure systems remain key challenges for the country, even with relatively abundant of water resources. Afghanistan lies within the heart of one of one of the region’s largest freshwater regions, the Hindu Kush Himalayan regions. Its major river systems are the Amu Darya, the Helmand, the Harirud and the Kabul. Only the Kabul River, joining the Indus system in Pakistan, leads to the sea. All four rivers cross international boundaries. These water resources are unequally distributed. The Amu Darya Basin, including the Harirud and Murghab Basin and non-drainage areas, covers about 37 percent of Afghanistan’s territory and contains about 60 percent of the water flow. It is one of the longest rivers in Central Asia and forms part of the country’s borders with Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The Harirud-Murghab represents about 12 percent of Afghanistan’s water resources and is centered in Herat, an intensely irrigated region of Afghanistan. The river flows through Iran, ending in Turkmenistan, and acts as a border between Afghanistan and Iran and further between Iran and Turkmenistan. The Helmand River Basin forms the Afghan-Iranian border for 55 kilometers and water is used primarily for irrigation. The Kabul River flows through Afghanistan and Pakistan and represents approximately 26 percent of the available water resources in Afghanistan. Annual precipitation is robust at 165,000 million cubic meters and there is adequate water flow due headwaters in its high mountains (Reigart and Wegerich 2010; Schroeder and Ure 2015; Yildiz 2017).

The country, however, lacks the capacity to store, use and manage those water flows and ranks among the weakest in the world in storage capacity. Drinking water supply and water for irrigation is the priority for the Afghanistan government, but the challenge of obtaining safe and reliable supplies of water in Afghanistan is heightened by the fact that water-resources data collection was suspended around 1980 due to war, conflict and the Soviet invasion. Subsequently, much of the institutional knowledge relating to water resources was lost and most of the country’s water monitoring equipment was destroyed, resulting in a dearth of technical capacity, infrastructure and modern equipment necessary for effective hydro-geologic investigation of potential water resources. Meanwhile, scientists estimate that the need for water in the Kabul Basin will increase by six-fold over the next 50 years, as levels of available water decline due to increasing temperatures and climate change. Only 27 percent of the country’s population has access to improved water sources and it goes down to 20 percent in rural areas, which is among the lowest percentage in the world. The percentage of people with access to improved sanitation facilities is at 5 percent nationwide and only 1 percent in rural areas. In Kabul, 80 percent of the people lack access to safe drinking water and 95 percent lack access to improved sanitation facilities (Yildiz 2017; Hessami2017; Duran 2015).

Only 10 percent of agricultural land is irrigated, with remaining cultivated lands utilizing traditional methods such as deep-water wells, which are compromising aquifers and groundwater resources. Population growth, urban expansion, more intensive agriculture and prospective mining operations and climate change will further stress existing water resources (United Nations 2016).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The legal framework for water is embedded within the Constitution, statutory Law, Islamic law and customary law. The Preamble to Afghanistan’s Constitution broadly states that its goal is to achieve a “prosperous life and sound living environment” for all citizens. Article 9 reflects the importance of sound management of natural resources, including water. These general constitutional guarantees are more particularly defined in Afghanistan’s statutory law and in particular the Civil Code and Water Law. The Civil Code mandates that water from rivers and their tributaries are public property. All people have the right to use water to irrigate or draw on a stream for irrigation of private lands, including for irrigation of crops and trees, so long as the usage is not “contrary to public interests special laws.” The Water Law of 2009 enforces the protections afforded by Article 9 of the Constitution through regulations aimed at promoting conservation, equitable distribution and efficient use of water. The Law reaffirms that water is public property and the government holds management authority over the resource. Water is free, although costs of investment and provision of services can be charged by service providers. The Water Law states that suitable water-use traditions and customs will be considered in fulfilling the rights of water users, adopts an integrated water resources management approach based on a transition towards river basin development, and contains a strong role for local stakeholder participation. Finally, the Water Law mandates that the Ministry of Energy and Water (MOEW) coordinate transboundary water issues (GIRoA 2004; GIRoA 1977; GIRoA 2009).

Both the Constitution and the Water Law provide that no law shall contravene the tenets and provisions of the holy religion of Islam in Afghanistan and that the rights of water users, including rights-of-way for water resources, shall be interpreted in accordance with the principles of Islamic jurisprudence respectively. Classical Islamic law treats water as being held in public trust and private ownership of water rights is generally forbidden. Islamic law prohibits a person from withholding or misusing water by polluting or degrading it. Finally, customary law prevails as the practical legal framework for water, although there is no single set of rules under customary law or traditional practices that have been codified. In general, customary law governs water use, resolution of water conflicts and water resource conservation. Control of water distribution in most villages remains largely in the hands of local mirab bashis or mirabs and through the kareez system. A kareez is an underground system that taps and channels groundwater for the purposes of irrigation and domestic supply (GIRoA 2004; GIRoA 1977; GIRoA 2009; Wegerich 2009; Khan 2013; Afghanistan Legal Project 2015).

The Water Law is intended to include the traditional structures while gradually transitioning to a more modern integrated approach to water resource management. Specifically, the permitting system envisioned by the Water Law is intended to promote a more coherent and coordinated system for regulating Afghanistan’s limited water resources. Implementation of the law, however, is incomplete and gaps in the existing regulatory system persist, resulting in disputes and even violence among individuals and entire communities (Wegerich 2010; UN 2016).

TENURE ISSUES

Both the 2008 Water Sector Strategy and the 2009 Water Law, which recognize both Islamic and customary law, articulate that water is public property managed by the government. The Civil Code of Afghanistan further states that rivers and tributaries are public property and every person can irrigate lands from that water, except where it is contrary to public interest or special laws. To better regulate water usage, the Water Law allows the use of water without a permit in the following circumstances: for drinking water, livelihood and other needs, provided the daily consumption does not exceed 5 cubic meters per household; navigational uses, provided no damage occurs to the banks and right-of-way area of the river and there is no adverse impact to the quality of water exceeding permissible norms; and fire extinguishing. The following uses or activities require approval of a permit or license issued by River Basin Agencies prior to undertaking: surface or groundwater use for newly-established development projects; disposal of wastewater into water resources; disposal of drainage water into water resources; use of water for commercial or industrial purposes; use of natural springs with mineral contents or hot springs for commercial purposes; digging and installation of shallow and deep wells for commercial, agricultural, industrial and urban water supply; construction of dams and other structures for impounding water when the storage capacity exceeds 10,000 cubic meters; and construction of structures that encroach banks, beds, courses or protected rights-of-way of streams, wetlands, kareezes and springs. Once a permit or license is issued a River Basin Agency may cancel or modify a permit if the water user, without justification, fails to utilize or over utilizes the amount of water that has been allocated to the user. River Basin Agencies may also cancel or modify a license or permit when adequate water is not available to support the use or national interests demand (GIRoA 2009; GIRoA 2008c; Afghanistan Legal Project 2015; United Nations 2016).

In terms of irrigation, a person who builds an irrigation canal on his own property has the right to use it any way he wishes and can exclude others unless they secure the owner’s permission. In terms of access of rights to public water for irrigation, by law, the distribution of water rights deriving from public streams should be determined proportional to each land’s need for irrigation through Irrigation Associations (IAs). IA’s can delegate responsibility for distribution of water within irrigation networks in designated areas to the registered IAs. Linkage between these new associations and the traditional management of irrigation systems is made under the Water Law, which allows IAs to delegate the management and responsibility of water rights to a mirab bashi or mirabs designated by the IAs (World Bank 2016b; United Nations 2016; Thomas et al 2012).

While it is mostly women who collect water for household use, cooking, family hygiene and even farming, women are often excluded from government decisions and have little influence on the major decisions on how this critical resource is governed, be it at the local, national or trans-boundary levels. The gap between water managers and women is beginning to be bridged by educating women so that they are encouraged to get involved in technical and managerial roles relating to water management (OSCE 2016).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS