Published / Updated: December 2017

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO

Overview

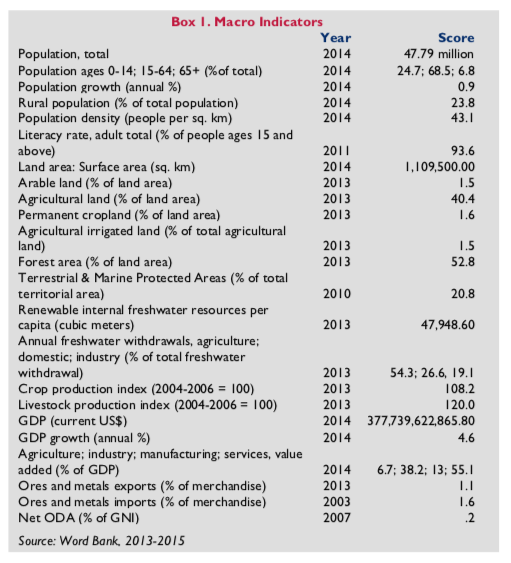

Colombia is the fourth largest country in South America with an area of 1.14 million square kilometers (approximately twice the size of France). It is one of the world’s most biologically diverse countries, with close to 14% of the planet’s biodiversity. Colombia has a wealth of natural resources, including extensive freshwater resources, the sixth-largest area of primary forests in the world, primarily in the Amazon basin, and a variety of mineral resources. Its coastal regions host increasing amounts of African palm, and it is the third largest producer of coffee in the world. Colombia’s population is 68% urban and 32% rural.

Colombia’s critical land issues stem from its colonial, agrarian past and the modern history of conflict which is its legacy. This legacy has also resulted in major displacement of people to cities which has exacerbated urban land issues, particularly in informal settlements. Forest and mining issues are the focus of much current policy attention. This profile focuses on Colombia’s land and natural resource situation. It explains the key land, water, forest and mineral issues and describes the ongoing set of policy and legal reforms aimed at addressing them.

Colombia was historically an agricultural society, and continues to rely strongly on agriculture for rural livelihoods. The landholding structure of colonial and post-colonial Colombia led, in the modern period, to a highly skewed distribution of land in which a relatively small group of landholders controls much of the good agricultural land, while a much larger group of rural inhabitants hold very small parcels. In rural areas, less than 1% of the population owns more than half of Colombia’s best land.

Colombia has a history of violent land-takings, beginning in 1948 and culminating in a civil war fueled by conflict between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and paramilitary militias established by landowners, local elites, and drug traffickers. A comprehensive peace agreement, which addresses land issues as a key part of Colombia’s peace planning, was negotiated and signed in December 2016. It is currently being implemented.

The conflict caused substantial displacement of rural people. Colombia has the second highest rate of internal displacement in the world surpassed only by Syria, with an estimated 5.7 million people having fled their land since 1985 (UNHCR, 2015), of which 87% are rural population (2015). This displacement has fueled the country’s swift urbanization and resulted in the creation of massive informal settlements in which residents lack tenure security and basic infrastructure. As a result, 3.8 million households, or 29.1% of all households in Colombia, do not have adequate housing, according to Ministry of Housing estimates from 2013, and another 662,146 families, or 5%, are homeless. Displacement has also left many rural people in precarious livelihood conditions with high poverty rates and lack of opportunities.

Land tenure is often insecure, particularly for small-scale farmers, indigenous and Afro-Colombian peoples, and members of women-headed households who have been forcibly displaced at disproportionately high levels. According to data from the Land Formalization Program (LFP) under the Ministry of Agriculture (2015), 48% of the 3.7 million rural parcels contained in the National Cadastre do not have registered titles. Approximately 1.7 million rural properties currently exist without formal property records.

Although successive government interventions have aimed at fostering land reform, these have historically been ineffective due to the conflict and the mixed record of government institutions responsible for reform. This may be changing as a part of the run-up to the peace process. In the last five years, two major legal reforms have taken place that focus on rural areas. These reforms promote land reform and reparation for victims. The reforms are spelled out in the 2011 law on land restitution and formalization for victims of violence (Law 1448) and a 2012 law that establishes a special process to develop a Land Formalization Program (Law 1561). The way that these laws are implemented will be a key part of the peace process and the establishment of an equitable and sustainable model of rural development and natural resource management for Colombia’s future. On December 7 of 2015 President Juan Manuel Santos signed a series of decrees under the special powers granted by Congress, which empower the GOC to make a comprehensive institutional reform to the agricultural sector.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

A Peace Accord to end Colombia’s civil war was signed in December 2016. The Accord includes agreements on six topics, including rural land. The Agreement grants land to landless farmers, and to formalize legitimate landholders who do not possess valid legal documents. The Agreement also aims to establish a state land fund of properties for allocation to landless households. The recent National Development Plan (2014-2018) incorporates these agreements and plans for their widespread implementation. Implementing these measures should serve as a fundamental platform for lasting peace.

To address rural tenure insecurity, Colombia has been developing a National Land Formalization Program since 2012 under the auspices of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. The Program establishes an expedited process for resolving the situation of the owners of urban or rural properties who lack legal documentation. The Program also provides legal security to those people that possess registered titles that contain legal deficiencies, enabling them to fully clear their rights. The Program is being implemented in two stages: the first phase was carried out between 2012 – 2014 for design and development; and the second phase will be implemented between 2015 and 2021 for national roll-out. The goal is to move away from a demand-driven titling effort and towards a systematic, offer-driven program in which land titles are provided as a public service in rural areas. This initiative is extremely important for the country to overcome the legacy of conflict and bring the benefits of formality including increased agricultural productivity, environmental sustainability, and a reduction of violence to small-scale farmers across the country.

To improve land-rights security in urban areas and housing conditions for millions of urban residents, as well as to foster growth and employment in the construction sector, the government and donors should work closely with local authorities and the private sector to support a country-wide regularization effort for informal settlements. Lessons learned from experiences in the 2000s in Medellin, Bogota and Cali can provide a basis for action. The government could promote provisional land-rights security through encouraging local authorities to designate informal settlements as “special social areas.” It could further assist in providing primary services such as water and sewerage to these communities, as well as longer-term land-rights security over time. The legal framework for adverse possession could also be explored as a tool for formalizing land rights of urban settlers as an alternative to expropriation.

Colombia’s land disputes complicate the formalization effort and initiatives for rural development and poverty reduction. New efforts are needed to mediate and resolve conflicts based on land and natural resources. USAID’s Land and Rural Development Program (LRDP) is currently helping the GOC to explore innovations such as a comprehensive, expedited land-mediation initiative which uses alternative dispute resolution (ADR) to resolve tenure security issues. LRDP is also providing support at the public policy level to use this dispute resolution initiative as the official tool to issue titles once a dispute is settled.

As of 2017, Colombia had 7.2 million officially registered IDPs. Providing IDPs with secure tenure and connecting them to government services and employment opportunities is a priority. For many IDPs, it may not be feasible or desirable to return to their place of origin. The government will need to work closely with IDPs and other stakeholders to develop acceptable strategies and policies to integrate displaced people in urban, peri-urban and rural areas where economic and social opportunities differ.

For IDPs and conflict victims land issues are at the heart of national reconciliation processes. The Law for Victims and Land Restitution (Law 1448 of 2011) provides for attention, assistance and reparations to displaced people and civilian victims of the conflict. The law is the centerpiece of the framework for transitional justice that seeks to create a post-conflict status based on the rights of victims to truth, justice and reparation, with guarantees of non-repetition. It is seen as a spearhead for the GOC’s broader land agenda and so political commitment to the Law is critical to ensure a multi-faceted land reform.

Tax incentives and government subsidies support large landholdings by wealthier families/groups, even if this land is under-utilized. These government interventions create land-market inefficiencies, and impede the distribution of land rights to potentially more productive users. They also contribute to continued socio-economic disparity in rural areas. As a preliminary step toward greater land-market efficiency and more balanced land distribution in rural areas, the government should be encouraged to remove tax incentives and subsidies that give distorted support to large landholders.

Colombia’s internal conflict and lack of policy enforcement has resulted in two major problems for mineral exploitation. The first involves situations where formal mining activity has triggered conflicts involving displacement of populations and land disputes. The second involves situations in which the mining sector has become a tactical or strategic objective of armed groups, including cases where mining facilitates the activity of these groups as a source of income, money laundering or territorial control. Resolving mining conflicts in the country is currently one of the biggest challenges the government faces, not only for its environmental implications, but also for the sector’s linkages to political, economic and social outcomes

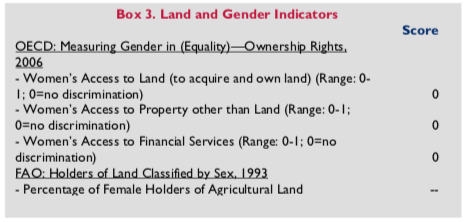

The Government of Colombia has enacted legislation favorable to women’s rights to land and property, but women-headed households remain especially susceptible to insecurity, poverty and the consequences of forced displacement. A focus on effective implementation of laws protecting women’s rights to land could improve living conditions for women and children in Colombia. The government and donors could continue to support gender training within land-administration bodies and launch a legal awareness/legal aid campaign that aims to increase awareness of women’s rights (LRDP’s work on televised programming is a possible model) and empowers women to exercise them. Programs should have a particular focus on vulnerable women, particularly Afro-Colombian and indigenous women, who are more likely to be displaced.

Summary

The history of Colombia has always been substantially intertwined with the institutions of land ownership (Constitutional Court, 2012). Much of the political, economic and social conflict in the country has historically involved rights over land, especially in rural areas, and the issue of state-sponsored land redistribution.

These issues continue to influence the country’s stability and development, as they support inequality in land distribution and insecurity of land rights for vulnerable populations. Land distribution in Colombia is highly inequitable: An estimated 0.4% of the population owns 62% of the country’s best land. Upward of 68% of the rural population lives below the official poverty level. The Government of Colombia (GOC) has attempted land reform programs designed to equalize land distribution and protect the rights of tenant farmers for decades, but with limited success. Large landholders have evaded reform, while institutions charged with promoting reform have suffered from internal corruption and lack the capacity to implement changes.

These issues continue to influence the country’s stability and development, as they support inequality in land distribution and insecurity of land rights for vulnerable populations. Land distribution in Colombia is highly inequitable: An estimated 0.4% of the population owns 62% of the country’s best land. Upward of 68% of the rural population lives below the official poverty level. The Government of Colombia (GOC) has attempted land reform programs designed to equalize land distribution and protect the rights of tenant farmers for decades, but with limited success. Large landholders have evaded reform, while institutions charged with promoting reform have suffered from internal corruption and lack the capacity to implement changes.

Land tenure insecurity therefore remains a widespread problem in Colombia. The failure of land reform, as well as escalating competition for resources, has fueled conflict between guerrilla insurgencies and paramilitary groups, with rural communities often caught in the middle. Over time, armed groups have gained territory by displacing smallholders from their land. Also, a lack of land administration tools means that private sector investments in land may not follow best practices for community engagement and consultation.

The new policies being set in place in support of the Peace Process are intended to change these institutional structures and address land distribution and insecurity of tenure. The legal framework tries to balance protection of private property with the state’s interest in promoting equity and efficiency through agrarian reform. Constitutional law thus provides for strong protections for private land holders, but also creates provision for state-led land redistribution. The Colombian Constitution (Article 58) states that private property and other rights acquired under civil laws are guaranteed. However, when the application of a law enacted for reasons of public utility or social interest results in a conflict with the rights of individuals, the private interest must yield to the public or social interest.

The Constitution also stipulates that it is the duty of the state to “promote progressive access to land for agricultural workers, individually or in partnership (…) in order to improve the income and quality of life of the peasants” (Political Constitution of Colombia, 1991, Article 64). In this way the Colombian Constitution stipulates that property has a social function; it implicitly creates obligations to use land for social purposes, and supports an inherent ecological function (Political Constitution of Colombia, 1991).

Within this broad constitutional understanding, the Civil Code of Colombia establishes five ways to acquire ownership of property: tradition, accession, succession upon death, occupation and acquisitive prescription, which is equivalent to adverse possession (Colombian Civil Code, 2015). Civil law is complemented by the Agrarian Law, which provides the state with the right to intervene in private landholding in cases where land’s social function is not being achieved, or to support land access for agricultural workers.

The reality of a legacy incomplete agrarian reforms, some of whose regulations were later overturned, and the displacement and neglect caused by decades of conflict, have created a great deal of uncertainty on the ground. The challenge of the GOC faces with a new set of land law reforms is to systematically update and clarify the information about the actual situation of all landholdings and apply the full set of legal instruments in ways which will facilitate national reconciliation and a create a sustainable model of inclusive rural development.

Land

LAND USE

Colombia has a total area of 2,070,408 square kilometers. In 2015, 56.9% of land was used for natural forests, and 38.3% was used for agricultural purposes (Third Agricultural Census, DANE, 2015). The balance of the country’s surface area is covered by waterways and urban areas.

Colombia’s land use varies according to the distinct geographic regions that make up the country. Colombia’s geography features coastal lowlands along both the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean. Lowlands along the Caribbean coast are mainly agricultural, while those on the Pacific coast are primarily swamps and dense forests. About one-third of Colombia is covered by the Andes Mountains. The southern and eastern regions of Colombia are part of the Orinoco and Amazon Basins and consist of inland plains and tropical forests. Just over one-half of Colombia’s territory is forested (56%), and nationally protected areas make up 25% of the total land area. There are 406,000 square kilometers of permanent grazing lands in the country (World Bank 2009; FAO 2009; FAO 2000; Vera 2001).

According to the agricultural census, 31% of agricultural land is use for pastures, though much of this land could be used for crop production and crop lands are significantly under-utilized (OECD 2015). Of Colombia’s cultivated land, 75% of the area is used for permanent crops, 16% for seasonal crops and 9% for intercropping. The country’s diverse topography and climate support a wide variety of crops including bananas, coffee, and cereals, as well as forest products and cattle-ranching (World Bank 2009; USDOS 2009a).

Rural land in Colombia is characterized by poor use of its natural potential, with much of the area either underutilized or overexploited. Nearly one-quarter of land used for grazing is prime agricultural land that could be better used for growing crops, while land that ideally should be conserved or left as forest is over-utilized for crops or grazing, resulting in erosion and destruction of forest and water resources. According to the GOC, only 40% of agricultural land is cultivated, due in large part to limited irrigation coverage (Grusczynski and Jaramillo 2002; Deininger 1999; GOC 2005). Land and natural resources in Colombia are degrading at a significant rate: over 2000 square kilometers of deforestation per year. Deforestation, erosion, and the silting of waterways negatively impact water and soil resources. While primary forests are cut, many marginal lands such as hillsides are cultivated, despite their lack of long- term agricultural potential (Grusczynski and Jaramillo 2002). A more rational land use pattern is called for.

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Of all rural land areas accounted for in the national cadastre, 22% are state owned, 52% are privately owned, 3% are held by Afro-Colombian communities, and 23% are held by indigenous communities.

Private lands are distributed in a highly unequal fashion. After independence, a dual landholding structure developed in Colombia, with latifundios (large landholdings) dependent on large numbers of agricultural laborers and minifundios (smallholdings) that made up the peasant subsistence economy. Over time, latifundios have grown, and land ownership has become even more concentrated, spurred by processes of displacement and illicit acquisition associated with the conflict and narcotics trade (UN Habitat 2005; Grusczynski and Jaramillo 2002; Elhawary 2007). From the early 1980s to 2000, armed groups are believed to have acquired approximately 4.5 million hectares of land, or roughly 50% of the country’s most fertile land (Elhawary 2007).

Unequal land distribution has been further supported by tax incentives and government subsidies that encourage the well-off to retain agricultural land even if they do not use it efficiently. Agricultural land is also acquired and held as a means of laundering drug money. Incentives to hold agricultural land have contributed to high land prices unrelated to the land’s agricultural value. By impeding land-market efficiency, these interventions also obstruct land from going to the most efficient users, potentially undermining food production and increasing pressure on forests and other sensitive land areas by smallholders or the landless (Deininger et al. 2004; Grusczynski and Jaramillo 2002).

Due to these historical processes, the predominant structural characteristic of Colombia’s rural landscape is the concentration of landholding in large properties with relatively low levels of land use intensity, interspersed with a large number of smaller parcels characterized by low levels of productivity on average. About 1% of the parcels cover more than half (53.8%) of the available land; while about 90% of the parcels share approximately one fifth of the agricultural land area. In other words, in rural areas, less than 1% of the population owns more than half of Colombia’s best land (DANE, 2015).

While the relative size of parcels varies across regions, this structural situation has been a root cause of political conflict around land, and the relatively low levels of overall rural productivity outside of certain subsectors like coffee. This inequality of land ownership and its impact on perpetuating poverty and disenfranchisement has been one of the country’s most problematic sociopolitical issues in the modern era.

Afro-Colombians have disproportionately high rates of forced displacement – upwards of 20-30% in some years (IDMC 2014). Traditionally located in the coastal areas of the Caribbean and Pacific regions, many have been displaced to urban centers as a result of conflict and threats of violence. In some cases, combatants have forcibly displaced communities, intending to take their land for commercial agricultural projects, such as palm plantations. In other instances, communities abandon their homes in response to approaching violence from armed groups. The majority of displaced Afro-Colombians are women (IRB 2008; USDOS 2009a; UN-Habitat 2005; Phelps Stokes Fund 2007; Monahan 2008; USAID 2008).

Rural-urban migration and the relocation of IDPs to urban areas have fueled rapid urban growth. Around 76%

of the Colombian population lives in urban areas while approximately 16% of the urban population resides in informal settlements (2004). Informal urban settlements develop illegally on public and privately owned land,

and are characterized by insecure tenure and lack of basic services. The GOC cites a scarcity of developable urban land as the primary impediment to expanding low-income housing in the formal sector. Other impediments include rigid regulations affecting land-use and construction, legal, technical and operational barriers to opening new areas to urban housing development, and a lack of access to financing (Everett 2001; Elhawary 2007; UN-Habitat 2005; Albuja and Ceballos 2010; GOC 2005).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The legal framework around land is based on multiple laws which regulate the protection of private, state and collective property and regulation of land markets. This framework includes planning regulations, balanced with laws which place limitations on landholding and use for purposes of agrarian reform. The two key reforms mentioned above—restitution and formalization—represent measures to update the legal situation of all land parcels in accordance with current policy priorities.

Colombia’s National Land Reform System was established by Law 160 (1994) to address the inequality of land ownership and to bring underutilized land into productive use by promoting transfers of land from large to smaller holders. It also established the process to legalize indigenous land rights and reserves. The collective recognition of Afro-Colombian black communities is established under Law No. 70 of 1993 (and regulated by Decree 1745 of 1995) which provides for a substantial collective titling program.

The creation of specialized courts with jurisdiction over rural land issues is one of points agreed on for the ongoing peace process. Currently, all rural land actions fall under the jurisdiction of ordinary civil courts, as established by General Code of Procedure (Law 1564 of 2012). These courts are widely viewed as having failed to provide sufficient attention to, and resolution of, rural land issues.

During the last decade, and particularly since 2012, in the prelude to the peace process a substantial set of legislative reforms have been undertaken to address the inter-related issues of displacement, legal uncertainty and land access in rural areas. The main legal instruments in this set of legislative reforms are the following:

Resolution 181 of 2013. This Resolution creates the Land Formalization Program and its Coordination Unit. This program aims to promote access to rural land and to improve the quality of life of the peasant population, coordinating those actions for supporting the matters related to:

- Formalization of ownership rights over private rural fields.

- Clearance of title in cases of incomplete or irregular documentation.

- Resolution of administrative, notarial and registration matters that have not been fulfilled.

- Promotion of a culture of formalization for rural property.

Law 1579 of 2012. This law regulates the notarial and registration processes for officially registering immovable property.

Law 1561 of 2012. This law establishes an expedited process for formalizing rights for valid occupants of urban or rural properties, and provides for an expedited procedure for cleaning registered titles that may have problems in the chain of title order to increase security. The key aspect of this special process is that it obligates judges to issue a ruling within approximately 6 months. This term can only be exceeded in case of interruption or cessation of the process for a legal cause.

Law 1448 of 2011: Land Restitution and Formalization Program for victims of violence. Law 1448 from 2011 (commonly known as Victims and Land Restitution Law) is part of the framework of transitional justice, which seeks to recognize the rights of victims of the Colombian armed conflict to land restitution.

With this law the government created the Special Administrative Unit for Land Restitution (URT), an administrative organ that promotes special judicial proceedings in order to restitute the lands of the dispossessed. The law also provides alternatives to the issues of secondary occupants and big investments that have caused displacement. The URT also manages the Unique Registration System for Dispossessed Lands (Spanish acronym RUTDA).

The formalization law and the restitution law are designed to work together. Any program that promotes formalization and/or land redistribution, must exclude those cases related to lands that have been reported or declared to be abandoned or dispossessed. Law 1448 creates the “Record of the Dispossessed and Forcibly Abandoned Land” which registers the lands and people who have been deprived of their lands or forced to abandon them. The register records their legal relationships and the precise location of the lands that were the object of dispossession (preferably by georeferencing) as well as the period in which there was armed actors’ influence. This register is under the responsibility of the URT.

Law 1453 of 2011. This law establishes the Fund for Rehabilitation, Social Investment and Fight Against Organized Crime – FRISCO (Fondo de Rehabilitación, Inversión Social y Lucha contra el Crimen Organizado), as a special account of the National Narcotics Directorate (Dirección Nacional de Estupefacientes) according to the policies established by the National Council of Narcotics.

The Fund has responsibility for the formalization and redistribution of the lands that have been confiscated by the government. In particular, properties which have received a declaration of extinction of ownership in criminal procedures, require formalization. The majority of these lands have not been regularized to date due to their informal occupation (in many cases by vulnerable populations), delays in tax and service payments or lack of clarity about their exact boundaries.

SECURING LANDED PROPERTY RIGHTS

Land tenure insecurity is a widespread problem in Colombia, which has a history of conflict and violent land takings. According to a recent study between 20 and 60% of land tenure in the country is held under informal arrangements (Bartel et al. 2016). An estimated 48% of the 3.7 million rural parcels registered in the National Cadastre do not have registered titles. An unknown number of parcels, estimated in the millions, are not in the National Cadastre. Informality inhibits investment and land transactions, reduces local revenue from property taxation, complicates efforts at land use planning, land restitution and agrarian reform, and facilitates illicit activities.

Since 1985, 7.21 million people are estimated to have abandoned their land due to conflict, or fled after their land was forcibly seized. IDPs have abandoned an estimated 4 million hectares (IDMC 2017).

Ownership rights acquired through purchase require registration of a transfer deed (UN-Habitat 2005). In some urban areas, it is relatively common to obtain ownership rights through adverse possession. Under the National Police Code, invaders may become possessors of private property in urban areas if not evicted within 30 days. In rural areas, invaders become possessors after 15 days. Per the Civil Code (Article 673), possessors of property may acquire property ownership through adverse possession if they meet the following conditions: a) the possessor holds the property as an owner, e.g. pays taxes and installs services in his/her name; b) the possessor holds the land for 10 years in urban areas, or five years in rural areas; and c) a judge declares adverse possession. Invaders can also gain occupation rights for certain classifications of state property. Adverse possession is regularly used in Colombia, and landowners may lose their land if they do not utilize their property. However, the poorest people – those who are most likely to live on invaded land – often lack the resources to prove ownership or tenure (UN-Habitat 2005).

Rural-urban migrants and IDPs often gravitate toward informal settlements with the intention of staying permanently. Some settlements have been subject to mass evictions, while others have been gradually annexed into cities. Local authorities may provisionally secure tenure rights for residents in informal settlements by designating these settlements “special social areas.” This designation is a binding declaration of intent by authorities to legitimize the settlement, legalize tenure claims, and implement infrastructure-improvement projects. Such a designation protects residents from eviction (Albuja and Ceballos 2010; Mertins et al. 1998; Macedo 2000). In rural areas, land may be obtained through the country’s land reform program. Law 160 (1994) provides subsidies for farmers to acquire land, with a preference for female-headed households. The subsidy covers 70% of the land’s cost. Law 812 (2003) modified this program to create an integrated subsidy for the development of productive projects including marketing and land improvement (UN-Habitat 2005), but had limited coverage in execution. Agrarian reform programs prioritized joint titling and the inclusion of female-headed households, resulting in improved rights for women through these programs. However, there is no requirement for joint titling in both spouses’ names when registering private land (UN-Habitat 2005).

The Land Formalization Program is intended to address the problem of informality nation-wide. The program is currently entering a phase of national roll-out, planned to be completed by 2021. Priority areas are being selected for the first large-scale field work to be carried out. Areas are being selected to prioritize areas with low indexes of dispossession, demands for formalization from the municipal and provincial governments, presence of agricultural policy programs, and the existence of a cadastral census in the municipality. As noted, the formalization program applies only to those properties that are not involved in the land restitution process (per Law 1448 of 2011).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Colombia has legislation favorable to gender equity. Women can legally own land. Further, men and women have equal land rights. Legislation also provides for the opportunity, though not the requirement, to adjudicate jointly and/or to title land to couples (Deere and Leon 2001).

The Law on Rural Women, Law 731 (2002), specifically recognizes the rights of women (whether married or in stable co-habitation) to agricultural reform parcels and calls for the participation of women in the allocation of parcels (UN Habitat 2005).

Married women and those who have been in a stable union for at least two years hold marital property as community property. In the event of divorce, separation, or death of a spouse, community property entitles each spouse to 50% of property acquired during the marriage. However, when marriages dissolve women must often get a letter from their former partner that is certified by a notary confirming the union. This document, along with others required to support their claims, such as extrajudicial declarations, civil records of children who have both the father’s and the mother’s last name, and testimonies of friends and neighbors may be difficult for women to obtain due to time and costs involved (USAID 2016).

Married women and those who have been in a stable union for at least two years hold marital property as community property. In the event of divorce, separation, or death of a spouse, community property entitles each spouse to 50% of property acquired during the marriage. However, when marriages dissolve women must often get a letter from their former partner that is certified by a notary confirming the union. This document, along with others required to support their claims, such as extrajudicial declarations, civil records of children who have both the father’s and the mother’s last name, and testimonies of friends and neighbors may be difficult for women to obtain due to time and costs involved (USAID 2016).

Under the Civil Code, when a spouse dies intestate the surviving spouse has the right to 50% of the community property. The remaining 50% is divided equally between all children, regardless of gender or legitimacy. Individuals can bequeath up to 25% of their property through a will. The rules of succession in the Civil Code govern the inheritance of the remaining property (UN-Habitat 2005). In addition to community property protections, property used as the family home is considered “homestead property,” regardless of when it was purchased or by whom. Such property can only be transferred or mortgaged with the consent of both spouses (Martindale-Hubbell 2008).

Despite legislation protecting women’s rights to land, these rights are often violated. Women are the most susceptible to forced displacement by armed groups. The percentage of women-headed households in Colombia increased from 26% to 31% between 1997 and 2003. During the conflict in Colombia more than 3.9 million women were displaced because of violence and threats to their safety and the safety of their families (USAID 2016) Women-headed households constitute 35–50% of all displaced households. Women-headed households and Afro-Colombian women suffer disproportionately from displacement and more frequently live in informal settlements. Women are also more restricted in their access to subsidies, credit, and adequate basic services.

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

As part of the preparation for the peace process and to achieve goals for land restitution, formalization and refocusing of agrarian reform, Colombia’s land and rural development institutions are also undergoing reforms. In December 2015 President Santos signed a series of decrees under the special powers granted by Congress, which empower the GOC to pursue comprehensive institutional reforms in the agricultural sector.

Recent Presidential decrees establish a new National Land Agency (NLA) with oversight of land issues, a new Ministry for Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD), a new Agency for the Renewal of the Territory, a Supreme Council for Land Use, a Superior Council for Land Restitution and a Directorate of Rural Women in the Ministry of Agriculture, among other changes.

The NLA is responsible for implementing national policy for rural property. To do this, the Agency will manage the access to land for production, will seek to achieve legal certainty in property rights and manage public lands to ensure their proper use. This new agency will allow the Federal Government to directly implement land formalization (barrido predial) in the areas which it identifies as priority areas (GOC Decree 2363 of 2015).

The MARD is responsible for implementing plans for comprehensive agricultural development projects. It should channel more resources into local regions and support small, medium and large producers by promoting producer associations. This new system is intended to ensure that producers will receive adequate technical and marketing assistance, as well as infrastructure (irrigation and drainage). Under this institutional framework, the MARD will be the lead agency for the trural sector.

The cadastral function (i.e., mapping and valuation of land parcels and buildings) in Colombia is carried out by the Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (IGAC) and decentralized, autonomous cadastral agencies under supervision of IGAC in Bogota, Cali, Medellín and the province of Antioquia. IGAC is the entity responsible for producing the official map and the basic cartography of Colombia; developing the national parcel map of properties; managing the inventory of soil characteristics; carrying out geographic investigations in support of territorial development; training and educating professionals in geographic information technologies, and coordinating the “Colombian Spatial Data Infrastructure” (Spanish acronym ICDE). Under the new multipurpose cadastre effort, the IGCA will have three offices: one for national planning, one for execution and oversight and regulation will be in the hands of the Superintendancey of Notaries and Registry (SNR).

Registration of legal rights to immovable property is managed by the Superintendency of Notaries and Registry (SNR). SNR guarantees the public record of property rights in Colombia through the provision of registration and inspection of property rights, supervision and control of the public notary service. It should be noted that the databases of IGAC and SNR are only partially linked, a situation that exacerbates the challenge of clarification and formalization of property rights in the country.

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Illegal land expropriation is a common legacy of the country’s history of conflict. The GOC is estimated to be responsible for approximately 1% of total population displacement through land expropriation, while the remaining 99% of displacement is due to extra-judicial processes. In order to address this problem, Legislative Decree 1 (1999) amended the Constitution to prohibit extrajudicial expropriation of private property. The decree further stipulates that compensation must be paid prior to expropriation (Reynolds and Flores 2008; Elhawary 2007).

Residents of informal settlements are sometimes subject to mass evictions. These evictions frequently relate to urban development; as urban land increases in value, residents of informal settlements are forced further and further to the periphery of cities. This is particularly true in Bogota, where neighborhoods on the periphery of the city are increasingly valued by developers. When evicted, residents are rarely offered compensation or resettlement opportunities (Albuja and Ceballos 2010; Everett 2001; UN-Habitat 2005).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Colombia has a history of violent conflict over land. The persistent failure of land reform fueled the emergence of guerrilla insurgencies, such as the Armed Revolutionary Forces (FARC) and National Liberation Army (ELN). In response, large landowners formed their own self-defense groups. As these paramilitary groups grew in power, they transitioned from defending large landholders to controlling territory. Paramilitary groups have gained territory by displacing smallholders from their land. This process has led to an estimated 2 to 4 million IDPs (Elhawary 2007).

The civil court system and customary dispute-resolution institutions generally handle land disputes. Indigenous Territorial Entities (ETIs) are allowed to exercise jurisdiction within their communities in accordance with their own customs, rules, and procedures. Neither the court system nor the customary dispute resolutions processes are adequately equipped, however, to handle issues related to restitution following mass displacement (UN-Habitat 2005; Elhawary 2007).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

Land in the peace process and in a post-conflict scenario are key issues. Agreements have been reached on five out of six topics, including rural land. In the Joint Draft for Integrated Rural Reform, agreement was reached to grant land to landless farmers and to formalize legitimate landholders who do not possess valid legal documents. The current Draft Agreement also aims to establish a state land fund of properties for allocation to landless households. The new recent National Development Plan (2014- 2018) incorporates these expected agreements and creates an approach for their widespread implementation. Implementing these measures could become a fundamental platform for lasting peace.

Land tenure and rural land rights interventions are critical issues to support the objectives of the National Development Plan and the peace process. To address rural tenure insecurity, Colombia has been developing a National Land Formalization Program since 2012 under the auspices of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. The program establishes an expedited process for resolving the situation of the owners of urban or rural properties who lack legal documentation. The program also provides legal security to those people that possess registered titles with legal deficiencies, enabling them to fully clear their titles. The Program is being implemented in two stages: the first phase was carried out between 2012 – 2014 for design and development; and the second phase will be implemented between 2015 and 2021 for national roll-out. This initiative is of utmost importance for the country to overcome the legacy of conflict and bring the benefits of formality including increased agricultural productivity, environmental sustainability, and a reduction of violence to too small-scale farmers across the country.

Urban land rights interventions remain a priority for action. To improve land-rights security in urban areas and housing conditions for millions of urban residents, as well as to foster growth and employment in the construction sector, the government and donors should work closely with local authorities and the private sector to support a country-wide regularization effort for informal settlements. Lessons learned from experiences in the 2000s in Medellin, Bogota and Cali can help to show the way. The government could promote provisional land-rights security through encouraging local authorities to designate informal settlements as “special social areas.” It could further assist in providing primary services such as water and sewerage to these communities, as well as longer-term land-rights security over time. The legal framework for adverse possession could also be explored as a tool for formalizing land rights of urban settlers as an alternative to expropriation.

Colombia’s land disputes complicate the formalization effort and initiatives for rural development and poverty reduction. New efforts are needed to mediate and resolve conflicts based on land and natural resources. USAID’s Land and Rural Development Program (LRDP) is currently helping the GOC to explore innovations such as a comprehensive, expedited land-mediation initiative with the use of ADR to resolve tenure security issues.

The land tenure issues of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) are another key priority for Colombia’s economic and social development. Colombia has 3.1 million officially registered IDPs. Providing IDPs with secure tenure and connecting them to government services and employment opportunities is a priority. For many IDPs, return to their place of origin is not a feasible or a desired option. The government could implement a comprehensive urban integration strategy, including the formalization of informal settlements where IDPs live, job training, and technical and legal assistance.

Land restitution and victims reparation for IDPs and conflict victims land issues are at the heart of national reconciliation processes. The Law for Victims and Land Restitution (Law 1448 of 2011) provides for attention, assistance and reparations to displaced people and civilian victims of the conflict. The law is the centerpiece of the framework for transitional justice that seeks to create a post-conflict status based on the rights of victims to truth, justice and reparation, with guarantees of non-repetition. The law’s implementation has begun, but it will require continued national commitment and integration with other parts of the land agenda to succeed at the required scale.

Tax incentives and government subsidies support large landholdings by the well-off, even if this land is under-utilized. These government interventions create land-market inefficiencies, impeding the distribution of land rights to the most productive users. They also contribute to continued socio- economic disparity in rural areas. As a preliminary step toward greater land-market efficiency and more balanced land distribution in rural areas, the government should be encouraged to remove tax incentives and subsidies that give distorted support to large landholders.

Mining and minerals extraction are another key area of natural resource tenure and management. Colombia’s internal conflict and lack of policy enforcement has resulted in two major problems for mineral exploitation. The first are situations where formal mining activity has triggered conflicts involving displacement of populations and land disputes. The second are situations in which the mining sector has become a tactical or strategic objective of armed groups, including circumstances where mining facilitates the activity of these groups as a source of income, money laundering or territorial control. Resolving mining conflicts in the country is currently one of the biggest challenges of the government, not only for it’s environmental implications, but also for the sector’s linkages to political, economic and social outcomes.

Gender equality is a key area that cuts across all land and natural resource issues. The Government of Colombia has enacted legislation favorable to women’s rights to land and property, but women-headed households remain especially susceptible to insecurity, poverty and the consequences of forced displacement. A focus on effective implementation of laws protecting women’s rights to land could improve living conditions for women and children in Colombia. The government and donors could institute gender training within land-administration bodies and launch a legal awareness/legal aid campaign that aims to increase awareness of women’s rights, and empowers women to exercise them. Programs should have a particular focus on vulnerable women, particularly Afro-Colombian and indigenous women, who are more likely to be displaced.

TENURE TYPES

Land in Colombia is classified as state property owned by the nation; private property owned by individuals; and communal land, which is possessed by indigenous groups, Afro-Colombian communities, and cooperatives or groups of urban dwellers (UN-Habitat 2005).

Land (other than communal land) can be held or acquired through: private ownership (freehold, unconditional, indefinite); possession without legal registration; invasion, if the invader is not promptly evicted from the property; simple tenure; user loans; rent; usufruct; house leasing; transit lots and temporary settlements (for IDP’s); assignment contract or provisional tenure; and joint ventures between private interests and the state (UN-Habitat 2005).

Communal land includes four types of holdings: (1) territories of indigenous groups, titled or untitled, which cannot be transferred or mortgaged; (2) territories of Afro-Colombians; (3) associative and/or joint property held by rural workers as cooperatives; and (4) urban community property (UN-Habitat 2005).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

One of the most important aspects discussed in the framework for the peace negotiations between the Government of Colombia (GOC) and the Colombia Revolutionary Armed Forces (FARC) is Comprehensive Rural Reform (CRR). The Comprehensive Rural Reform (CRR) effort is intended to create important structural changes in the rural and agrarian environment of Colombia based on principles of equity and democracy. The aim is to address the structural roots of conflict to prevent its recurrence and contribute to building a stable and lasting peace.

CRR is focused on the welfare of rural people, including peasants, indigenous, black, Afro-palenqueras communities and island populations. It aims to achieve the integration of regions, eradication of poverty, promotion of equality, closing of the gap between cities and the countryside, the protection and enjoyment of rights of citizens and the reactivation of the rural sector, especially the rural economy (Peace Process draft, 2014).

The previously mentioned Agrarian Jurisdiction (Jurisdicción Agraria) originally created by Decree 2303 of 1989) is part of the CRR. It is comprised of judges with specific knowledge of agrarian law that are empowered to directly resolve all conflicts related to rural land and affairs. The Agrarian Jurisdiction is designed with the aim of protecting vulnerable groups and economically weaker parties.

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

The international community is assisting the GOC with land and natural resource policy reforms. The United States of America, the World Bank, UNDP, UNEP, UN-Habitat, the EU and several other donors are providing technical and financial assistance under a variety of programs.

One of the largest donor-supported programs is USAID’s Land and Rural Development Project (LRDP). In collaboration with key GOC institutions and other actors the Project supports the development of tools, systems, and skills to enable the GOC to fulfill its mandate to resolve the land issues at the heart of the conflict. The Project is helping to build the capacity of the institutions to administer and manage the programs to restitute land to victims of conflict and extend land titling in prioritized rural areas. In collaboration with the public and private sectors, the Project is also promoting sustainable rural development to enable beneficiaries of land interventions to retain and make productive and efficient use of their land. The LRDP’s activities in Colombia have an anticipated budget of approximately $65,000,000 (USAID, 2015).

A Superintendence of Notary and Registry (SNR) is in the process of designing and rolling out a new internal electronic platform that provides legal analyses of land parcels—including information about who the landowner is, the legal state of the land, and whether the land is micro-focalized (and thus available for restitution). This information is critical to conducting efficient and timely land restitution processes. Previously, when a GOC entity needed this type of information, it had to mail in a formal request to the SNR, which would then process it manually and mail it back. With the new electronic system, which was supported by the LRDP project, the legal analysis is performed on demand, which reduces processing time by 50% and eliminates the time needed to access information (USAID, 2015).

Also through LRDP, USAID actively supported a team of high-level GOC and international experts to design Colombia’s Misión Rural, a policy and action framework that represents the GOC’s 20-year vision for the country’s agriculture and rural development sectors, and includes the reforms outlined in the peace negotiations. The framework includes recommendations for short-, mid-, and long-term solutions that will open markets, improve land use, resolve bottlenecks, increase social inclusion, and decentralize GOC efforts. It also supports a massive formalization effort that will help address agreements in the Peace Accord. Critical LRDP inputs that were adopted include the creation of two new entities, the Land Authority and Rural Development Fund. Short-term solutions have been delivered to President Santos with recommendations for implementation using his extraordinary powers (USAID, 2015).

The World Bank has been, and continues to be, a major supporter of the rural land agenda in Colombia. The WB’s project to prevent forced displacement, the Protection of Patrimonial Assets Internally Displaced People project, laid an important foundation for the restitution law and program. One of the project’s important innovations was the development of a social mapping technique which shows resettlement locations per municipality. Using official cartography or aerial imagery, neighbors were able to identify their property locations. This approach allowed those affected to exercise social control over the legitimacy of land claims since no one person could single-handedly claim a right to a particular parcel of land. The methodologies and procedures developed by the project were incorporated into a Decree of the National Plan for the Assistance to the Displaced Population, which made the application of new land protective measures mandatory.

In 2016 the World Bank’s Subnational Government program will start assisting rural municipalities with land use plans (Planes de Ordenamiento Territorial) and is expected to provide financial and technical support to cadastral updating nationally.

The UN system, particularly UNDP, UN-Habitat is an important partner of the GOC in the land agenda.

UNDP has been a key supporter of the peace process with a strong focus on land displacement and restitution. UNDP was requested by Colombia’s Congressional Peace Commissions to organize 18 regional fora to gather input from civil society on the issues on the peace agenda, ranging from rural development, to illegal crop substitution, to victims’ rights. Subsequent consultations, requested by the Government and the FARC rebel group focused on land issues and political participation. The results of these consultations contributed to the enactment of the 2011 Victims and Land Restitution Law. With a significant presence in remote, conflict-affected areas and offices in eleven departments, UNDP Colombia also oversees major programs aimed at reducing poverty—which is most acute in rural areas— supporting good governance, and promoting inclusive, equitable economic growth.

UN-Habitat is active in urban land issues in Colombia, with ten on-going projects including piloting an inclusive and participatory land readjustment activity in Medellin, support for the national urban strategy development, and securing land for affordable housing in Medellin.

German international cooperation is supporting the GOC in three priority areas which link to land issues. These areas are peace building and crisis prevention, including support to displaced peoples, environmental planning including local land use and degraded land restoration, and sustainable economic promotion.

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Colombia is ranked as one of the world’s richest countries in terms of aquatic resources. The country’s large watersheds feed into the five massive sub-continental basins of the Amazon, Orinoco, Caribbean, Magdalena-Cauca and the Pacific (CBD, 2013). The basin of the Magdalena River, the country’s most important river system, covers one-quarter of Colombia. Colombia has an average water yield equivalent to 6 times the world average and three times Latin America’s. Its groundwater reserves are over three times annual yield and are distributed across 74% of the country (IDEAM, 2015a).

According to IDEAM estimates (2015), the total water demand in Colombia is 36 million cubic meters/year. This breaks down into the following use pattern: agricultural 46.6%; energy 21.5%; aquaculture 8.5% and household 8.2%. As of 2007, 900,000 hectares of land were under irrigation. Two-thirds of these were privately developed. The GOC relates underutilization of agricultural lands to poor irrigation coverage (EarthTrends 2003; FAO 2000, World Indicators 2008).

In spite of the abundance of fresh water, distribution of drinking water in rural areas is a problem; 26% of the rural population has no access to improved drinking water, and 94% do not have access to adequate sewerage and sanitation (UNDP, 2015).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Under the Constitution (1991), the GOC is responsible for the management and use of natural resources to ensure the sustainable development and conservation of those resources. Law 99 of 1993 establishes The National Environmental System (SINA) under the Ministry of Environment as the policymaker and management authority for water at the national level.

Since the SINA law was established, the current set of regulations for the water sector has been developed. The main regulations are those for efficient water use and conservation (Law 373 of 1997); the national policy document on water management (Document 1750 of 1995); the provisions for wetland protection, conservation and sustainability (Resolution 769 of 2002); the regulation of technical standards for drinking water (Decree number 475 1998); and the regulation of surface waters, including estuary waters and groundwater and coastal aquifers (the Resolution 769 of 2002 and Decree 155 of 2004).

More recently, the first scheme for payment for environmental services (PES) in Colombia for the protection of water sources was established (Decree 953 from May 2013).

The current policy for providing drinking water and basic sanitation in rural areas was established in 2014 (CONPES document 3810). The policy is intended to articulate and implement the necessary actions to increase the coverage of the population with access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation in rural areas of the country, to improve living conditions and health and decrease the poverty gap between the urban and rural population (CONPES, 2014).

TENURE ISSUES

Water is considered a public resource, but private service delivery is permitted based on 1991 constitutional changes (Barrera-Osorio and Olivera 2006).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The current National Development Plan (NDP) 2014-2018 establishes the National Water Council as a coordinating body for the integrated management of water resources. The Council is composed of the Director of the National Planning Department, the Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development who manages the Technical Secretariat, the Minister of Mines and Energy, the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Minister of Housing, Cities and Territory and the Minister of Health and Social Welfare.

The Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Housing, Cities and Territory and the Ministry of Agriculture are responsible for specific policies on water use, for example for financing and constructing public irrigation networks (Ministry of Agriculture, 2015). Regional Autonomous Corporations (CARs) and Urban Environmental Authorities are also endowed with administrative and financial autonomy to administer water resources within the overall regulatory framework (OECD, 2015). The NDP states that the Government will define specific schemes for the provision of services for water supply, sewerage and sanitation in rural areas, especially for areas that are difficult to access and manage.

Regulation of local water utilities is carried out by the Regulatory Commission for Drinking Water and Sanitation (CRA), which is composed of the Environment Minister; the Minister of Housing, Cities and Territory; the Health Minister; the Director of the National Planning Department; the Superintendent of Public Services and a group of experts. The CRA’s objective is to regulate water utilities to avoid monopolization and promote competition when possible, searching for economic efficiency of the water and solid waste utilities and encouraging the provision of good quality services. In particular cases, the Commission creates rules for specific utilities depending on their market conditions (CRA, 2015).

Conflicts over water quality in Colombia are usually associated with the presence of unplanned towns and erosion due to unplanned construction or other development. Conflicts over the quantity of water being used usually stem from the inefficient use of water resources by large industrial or agricultural users, the natural conditions of the basin (such as intermittent streams), and illegal water uptake.

One of the major areas of conflicts related to water involves high-altitude wetlands (paramos) and mining. In Colombia there are 36 major high-altitude wetlands in three mountain ranges and in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. This is the largest concentration of high-altitude wetlands in the world. These ecosystems over nearly three million hectares, representing 50% of the Andean highlands (Humboldt Institute, 2013), and are considered strategic because they provide important ecosystem services — water being the most important environmental service. It is estimated that 70% of the Colombian population depends on water from these wetlands (The Humboldt Institute 2013). Four hundred municipalities have jurisdiction over wetlands which contribute to the water supply for about 20 million people.

A large number of the wetlands are at risk and threatened by mining and the lack of an effective state regulatory presence. The National Mining Agency has reported that in Colombia there are 364 mine titles in wetland areas. These mine titles for the exploration and development of coal, gold, minerals, zinc and other mineral deposits, cover almost 80,000 hectares of wetland (El Colombiano newspaper 2015).

The current discussion on this matter is aggravated by the legal framework. The National Development Plan (NDP) recognizes the legitimacy of mining rights that were granted before 9 February 2010. In other words, the mining titles that were granted before 2010 may continue to operate until 2039. It is therefore important to promote a dialogue between the government, mining companies and communities, to balance the need for development with efforts to ensure the preservation of the wetlands and water.

The NDP establishes that from 2015 onwards the Ministry of Environment, Housing and Territorial Development can partially or totally restrict the development of mining and hydrocarbon development in wetlands, based on technical, economic, social and environmental studies in accordance with national guidelines (NDP 2014).

Dispute resolution for water resources is the responsibility of the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development. It is charged with resolving discrepancies between entities for the use, management and exploitation of renewable natural resources. If the Ministry cannot resolve an issue, disputes are resolved in courts.

Community involvement in water resources decisions is also possible. Article 79 of the Constitution of Colombia empowers communities to take part in decisions that affect them. Similarly, Decree 1640 (2012) establishes basin councils to represent and advise all actors who live and develop activities within the basin to “contribute with alternative solutions in processes of conflict management related to the formulation or adjustment of the River Basin Management Plan and the management of the renewable natural resources of the basin” (OECD 2015).

One of the greatest challenges in water resources that the country needs to address is reducing inequalities between urban and rural areas for water access and quality. Colombia is continuing to design and implement projects to increase access to water and sanitation in rural areas for vulnerable populations. These efforts include infrastructure projects such as rainwater harvesting systems; household filters for water purification; construction and improvement of latrines and composting toilets; and improving water and sewer infrastructure. These projects are accompanied by strategies that promote community ownership and sustainability (UNDP 2015).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Colombia’s water sector has undergone two major reforms in recent decades. First, municipal governments have been charged with service delivery. Second, Constitutional reforms in 1991 permitted private participation in water service delivery. Though unpopular, privatization has positively affected welfare, especially in urban areas where access to safe water has increased (Barrera-Osorio and Olivera 2006).

The National Environmental System (SINA) is composed of 33 autonomous regional corporations which manage Colombia’s forests. Through the system of regional corporations, the country emphasizes watershed reforestation projects and protection (ITTO 2005).

The 2014-2018 National Development Plan calls for a widened scope of action for regional water suppliers, including permitting exclusive service areas, in order to provide drinking water and sanitation to rural areas.

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID has worked with the Colombian Ministry of Health to develop community enterprises to manage the delivery and distribution of water services (USAID 2006). USAID also supported the Semana Foundation to provide access to water in rural schools in one of the most conflict-affected departments of Colombia. Access to water remains a key issue for communities and for farmers. Lack of water constrains economic growth and negatively impacts health of Colombian communities, especially though along the Caribbean coast.

A component of USAID’s ADAM project supports the creation of improved water and sanitation facilities for IDPs. The World Bank, the United Nations Childrens’ Fund (UNICEF), the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Spanish government fund water supply and sanitation projects.

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Forests cover 60 million hectares, or 57% of the national territory of Colombia (DANE, 2015). Eighty-seven percent of the country’s forests are primary forests, which gives Colombia one of the largest areas of primary forest in the world. The country also has cloud forests, a moist and humid environment that is home to low trees, mosses, and ferns that capture moisture from clouds and provide a unique habitat for rare and endangered species (FAO 2009; FAO 2005; Bubb et al. 2004).

Colombia has several areas of high biological diversity in the Andean ecosystems. These are characterized by a significant variety of endemic species. The Amazon rainforests and the humid ecosystems in the Chocó biogeographical area are the next most biologically diverse areas in the country. As a result of complex variations in climate, topography, and soil, Colombia is home to 10% of the world’s biodiversity, making it the second most biodiverse country in the world (Vera 2001; FAO 2005; Hagan n.d.; FAO 2009).

A considerable part of these natural ecosystems has been transformed for agriculture, primarily in the Andean and Caribbean regions. It has been estimated that almost 95% of the country’s dry forests have been reduced from their original cover, including close to 70% of typically Andean forests (CBD, 2013).

Deforestation in Colombia threatens the country’s vast biodiversity and is a contributor to carbon emissions, primarily in the Amazon forest. The annual rate of deforestation is estimated to be between 0.1% and 0.9%. In 2014, Colombia lost an estimated 1670 square kilometers of forests, which was a 16% increase over the rate of deforestation in 2013 (IDEAM, 2015b), but slower than the rates experienced in the early 2000s. Deforestation rates are highest in the Amazonian provinces, with the highest rate in Caqueta.

The government has been unable to fully safeguard designated protected areas and, as a result, original forests are being harvested along Colombia’s frontiers. Deforestation is caused by agricultural expansion, indiscriminate logging, and the collection of fuelwood. People who settle within protected areas are often able to obtain formal title over time, encouraging continuing forestland encroachment and clearing (GOC 2007; FAO 2009; Grusczynski and Jaramillo 2002).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

A new General Forest Law was adopted in 2006 (Law 1021). Major goals of this law include encouraging the development of plantations and natural forests, as well as the protection of the territorial rights of Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities over their forests. The law also regulates forest concessions. The Constitutional Court of Colombia has challenged this law and it is not currently being enforced (Reynolds and Flores 2008; USAID 2006; ITTO 2006). Actual forest management is largely carried out under the auspices of the Autonomous Regional Development Corporations as part of their environmental management function. The Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development has the authority for forest management within National Parks.

Under the Constitution, indigenous groups are able to participate in decisions about the exploitation of natural resources within their territories (UN-Habitat 2005).

Colombia’s forests are also protected under the Code of Renewable Natural Resources (Decree 2811 of 1974); the Law 99 of 1993 and its implementing regulations; the National Forest Policy of 1996 (Law 1021); the National Forestry Development Plan; the 1995 biodiversity policy and other general related regulations.

TENURE TYPES AND SECURITY

Forest ownership is both private and public, and includes ownership of the surface area and the trees. Private forest land is composed of private property and collective property, which includes indigenous land and the land of Afro-Colombian communities. According to the Rights and Resources Initiative (2012), there are 31.4 million hectares of public forest lands administered by the Colombian government, and 29.9 million hectares of private lands owned by communities and indigenous groups (26.4 million in indigenous territories and 3.4 million in Afro-Colombian communities).

The communal territories of both indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities are inalienable, protected from seizure, and exempt from statutes of limitations. (Political Constitution of 1991, Art. 63; Law 70 of 1993, Art. 7).

Seven major Forest Reserve Zones (ZRF), which can be public or private, were established through Law 2 of 1959. These areas are designed to support the development of the forest economy and to protect soil, water and wildlife. They are not technically protected areas, although protected areas within the National System of Protected Areas (SINAP) and collective territories of ethnic communities can be established within these zones.

There is also a Forest Producer Reserve called ‘Cuenca Alta del Rio Bogota’ (RFPPCARB), delimited by the Ministry of Environment through Resolution 0138 of 2014 with an area of approximately 94,000 hectares.

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Forest management is part of the National Environmental System (SINA). The SINA is led by the Department of the Environment, as principal agency of the policy and regulation. SINA integrates thirty-four Regional Autonomous Corporations for Sustainable Development which act as regional environmental authorities; five research institutes; five urban environmental authorities in the main cities; and a Unit of Natural National Parks (CSU 2015).

The Map of Ecosystems in Land, Marine and Coastal Ecosystems Colombia (IDEAM, 2009) provides the methodological reference for tracking and monitoring the status of forest areas in the country. It was established in 2007 to standardize methodologies and classification systems used for analysis, monitoring and evaluation of the country’s ecosystems. It is managed by the Environmental Research Institutes, which are appointed by SINA and the Agustín Codazzi Geographic Institute (IGAC).

There is a National Program for Monitoring Forests and Suitable Areas for Forestry (PMSB in Spanish) which has established strategies and actions to study, update and provide information on the dynamics of forest demand and to generate information related to areas that are suitable for forestry, in order to inform, guide and alert administrators and decision makers.

The PMSB’s vision is that by 2025 it will be established as an inter-agency, comprehensive program, used by different actors in the forestry sector on an ongoing basis for decision-making, research and adjustments to environmental policy and legislation.

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

In recent decades, Colombia’s governments have tended to focus on the political conflict and the need for economic development. Environmental protection and forest management were often accorded a relatively low priority. This has begun to change in recent years. Colombia signed up to the “zero deforestation in the Amazon by 2020” pledge at the CBD COP 9 in Bonn in 2008 and began preliminary work on REDD+ in 2009 (REDD desk 2015).

Colombia has played a leading role in the UNFCCC REDD+ negotiations where it supports market-based mechanisms. It has been a vocal proponent of the idea that REDD+ should accommodate a stepped, subnational approach, not only to reference levels and MRV (Government of Colombia 2012) but also in terms of eligibility for phase 3 of REDD+ (results-based payments) (the REDD desk 2015).

In this context Colombia’s REDD+ program officially started in 2015 as a joint program of the Ministry of Environment, IDEAM and the UN system. This program, which will last three years and will have an investment of $4 million, will support the participatory preparation of an incentive mechanism for reducing emissions from deforestation (UN Colombia 2015).

As specified in the National REDD+ Strategy (Estrategia Nacional REDD+; ENREDD+), the institution in charge of developing the reference level for Colombia is the Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (Instituto de Hidrología, Meterología y Estudios Ambientales; IDEAM).

Colombia’s National Development Plan (NDP 2014-2018) contains a specific article on the subject of forests in Colombia. This article (Article 171), specifies the ‘prevention of deforestation of natural forests’ as a national policy priority. The NDP establishes that the Ministry of Environment, Housing and Territorial Development will develop a national policy to combat deforestation which will include a plan of action to prevent the loss of natural forests by 2030. This policy will include provisions to substantively link to the sectors that act as drivers of deforestation, including supply chains that use the forest and its derivatives.

This policy will create specific goals with the participation of producers’ associations, under agreements for sustainability, where producers commit to rehabilitate degraded forests, as part of their economic activity.

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Several international donors are assisting Colombia with forest management. Among these, the USAID Biodiversity — Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (Bio-REDD+) project, is helping reinforce Colombian efforts to sustainably manage and use environmental assets by mitigating and adapting to climate change, preserving biodiversity, and promoting formalization and legalization of artisanal gold mining (Chemonics 2015).

The project is enabling the Colombian government — in collaboration with local communities, local nongovernmental organizations, and private sector investors — to sustainably protect and manage the country’s biodiversity, ecosystem services, and natural resources. It implements low-carbon and carbon reduction plans to mitigate the emissions of climate change gases. Bio-REDD+ has developed an approach that links forest conservation and issuance of carbon credits to income generating activities and biodiversity management.

The World Bank is a major supporter of GOC’s forest management activities and is supporting REDD+ through the Forest Carbon Partnership REDD+ Readiness program.

The World Bank’s main project is the $45 million Forest Conservation and Sustainability in the Heart of the Colombian Amazon Project for Colombia. The Project’s objective is improve governance and promote sustainable land use activities in order to reduce deforestation and conserve biodiversity in the Project area. The project has four components: (1) Protected areas management and financial sustainability; (2) Forest governance, management, and monitoring (3) Sectoral programs for sustainable landscape management; and (4) Project coordination and management.

The World Bank has also created a partnership with the pencil producer Faber-Castell in the El Magdalena watershed region which creates jobs for the local community and helps rehabilitate over 3,000 hectares of degraded land. The partnership provides lessons for a program that optimizes different land uses in one of the world’s last agriculture frontiers—Colombia’s Orinoquia region—covering over 28 million hectares and four Colombian departments.