Overview

The West African country of Côte d’Ivoire is divided between two large agro-ecological zones: the northern savannah zone, where food crops, cotton and livestock predominate; and the fertile forest zone of the south, where most of the country’s cash crops, including cocoa and coffee, are produced. Nearly 64% of land in Côte d’Ivoire is used for agricultural purposes, and 68% of the labor force works in agriculture.

Almost all farmland is held and transferred according to the rules and norms of customary law. Land is viewed as belonging to the lineage of the original inhabitants of an area. A village chief or other notable can allocate use of the land to extended family members or, as often happens in the south, to outsiders. Because customary procedures for the transfer of land are not well defined or consistently applied, their use has led to conflict, especially in the last few decades as population growth, immigration and commercialization of agriculture have increased competition for land.

In 1998, with assistance from the World Bank, Côte d’Ivoire adopted the Rural Land Law, which aims to transform customary land rights into private property rights regulated by the state. Because of an extended period of political turmoil from 1999 to 2011, and lack of resources devoted to the effort, very little has been done to make the Rural Land Law a reality for most Ivoirians.

Unsustainable farming techniques and a growing demand for fuelwood and commercial timber have decimated Côte d’Ivoire’s natural forests, which have declined from approximately 13 million hectares when the country became independent in 1960 to 2.5 million hectares in the 1990s. Coastal wetlands are also rapidly disappearing. Soil degradation, water pollution and loss of biodiversity pose significant threats to future productivity and the wellbeing of rural communities.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

Moving toward a rural land tenure regime that is governed by statute, rather than by custom, has proved to be an enormous challenge in Côte d’Ivoire. The Rural Land Law, adopted in 1998, remains little known and little used. The government would be well advised to reexamine the relationship between customary and statutory land systems and, in consultation with customary groups, decide whether the current statutory system needs adjusting to create a regime that best satisfies the needs of the rural population. The donor community should promote dialogue involving the government, customary groups and other rural land users to understand what paths may be available for systematically reducing uncertainty and conflict over rural land. Donors should also support training and orientation of rural land administration staff.

Custom excludes women from land ownership even though they produce and market most of the food in Côte d’Ivoire. A woman’s access to land is based on her status within the family and involves only the right of use. Of particular concern is a widow’s right to remain on the land she farmed while her husband was alive. The 1998 Rural Land Law reverses traditional practices with respect to women and land, granting them rights equal to those of men. However, to make land rights a reality will require engagement at the village and family levels as the Rural Land Law is implemented, to ensure that women are issued individual title deeds. Donors should assist the government by piloting projects to guarantee women’s land rights through legal education programs targeting rural women and men. Donors should also consider helping the government to employ and train a cohort of community paralegals to provide such education as well as assist poor rural women and men in asserting and securing their land rights. Enforcement of women’s rights must be an integral part of implementation of the Rural Land Law.

Customary practices for dispute resolution, involving compromise and the avoidance of a zero-sum, winner-take-all outcome, appear to be better suited to resolving land conflicts than is the formal judicial system. The problem is that the mediators, usually village chiefs or other traditional authorities, are often viewed by migrants as not impartial, and, by younger autochthones, as illegitimate. Donors should support NGOs with expertise in alternative dispute-resolution that can assist traditional and local governmental authorities to establish mechanisms to resolve disputes with an eye not only to protecting individual rights, but to preserving social cohesion.

Major consequences of land tenure insecurity in Côte d’Ivoire are: unsustainable farming practices; deforestation; loss of biodiversity; and a generalized degradation of the environment. The Rural Land Law creates rural land-management committees at the village level that can help to educate local farmers on environmental protection and sustainable farming methods. Donors should support programs of the Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development to train farmers on environmental issues.

The water and sanitation infrastructure in Côte d’Ivoire fell into a state of disrepair during the armed conflict of 2002–2007; in consequence, the proportion of Ivoirians with access to safe drinking water has been significantly reduced. At the same time, the legal framework governing the water sector has remained unclear. Although the Government of Côte d’Ivoire (GOCI) passed the Water Code in 1998, it still has not passed implementing regulations. The GOCI created and transferred water-related responsibilities to the Ministry of Water and Forests (MINEF) in 2011 and approved a National Action Plan for Integrated Management of Water Resources in 2012. Donors should support recent efforts to create a coherent water-management strategy in Côte d’Ivoire, including technical assistance for systematic monitoring of water resources, and repairs and improvements to water and sanitation infrastructure.

Summary

Côte d’Ivoire was for the two decades following independence in 1960 the envy of its neighbors. The country enjoyed political stability and strong economic growth thanks to policies that stimulated agricultural development with a strong focus on the cash crops cocoa and coffee. The farms were not large plantations but small landholdings, many in the hands of migrant farmers coming from other parts of Côte d’Ivoire or from neighboring countries.

Côte d’Ivoire was for the two decades following independence in 1960 the envy of its neighbors. The country enjoyed political stability and strong economic growth thanks to policies that stimulated agricultural development with a strong focus on the cash crops cocoa and coffee. The farms were not large plantations but small landholdings, many in the hands of migrant farmers coming from other parts of Côte d’Ivoire or from neighboring countries.

Beginning in the 1980s, however, rapid population growth and urban-to-rural migration put increasing pressure on natural resources and led to social conflict over land. In 1999 the government was overthrown in a coup d’état that triggered a series of political crises and armed conflicts lasting until 2011. At the heart of the turmoil was a debate over who should control the land.

Although under the laws of Côte d’Ivoire the land belonged to the state, the government had always in practice accepted customary law, which held that land belonged to the lineage of the people who first settled and cultivated it. While the members of the lineage could not sell the land collectively owned by the lineage, they could grant use rights to anyone, including foreigners. The government encouraged customary holders to lend land to those who would make it productive, and liberal immigration policies resulted in foreigners settling in Côte d’Ivoire by the millions.

In the mid-1990s, recognizing that tenure insecurity was causing angry disturbances in the countryside and was discouraging farmers from investing in their land, the government set out to establish a new legal framework for land tenure, which became the 1998 Rural Land Law. The law transforms customary land rights to private property rights regulated by the state. Because of armed conflict and the government’s lack of capacity, however, the law has not been effectively implemented.

Côte d’Ivoire has relatively abundant water resources, although water is more scarce in the north of the country. Increased urbanization, and damage to water and sanitation infrastructure during the civil conflict have decreased the proportion of Ivoirians with access to safe drinking water and increased water pollution. The GOCI has moved toward integrated water resource management in recent years, simplifying the institutional framework in 2011 and approving a National Action Plan for Integrated Management of Water Resources and pushing for approval of an implementing decree for the 1998 Water Code in 2012.

Côte d’Ivoire has small but growing mining and petroleum sectors, governed by the Mining Code and Petroleum Code, respectively.

Land

LAND USE

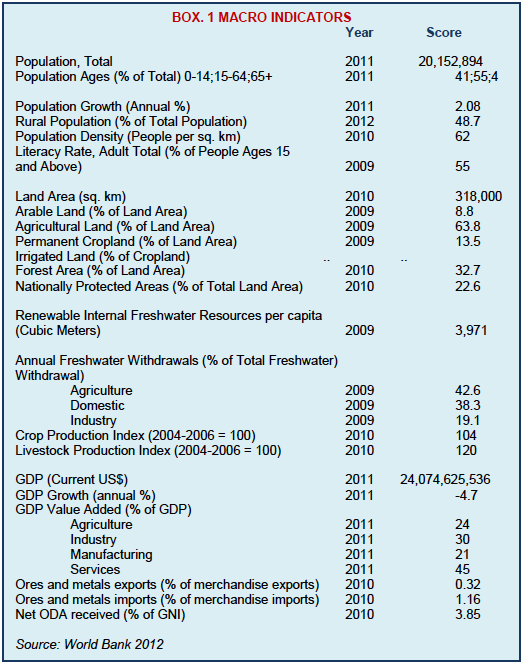

Côte d’Ivoire, located on the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa, for the most part has a flat to undulating terrain, with hills in the west of the country. Its neighbors are Liberia and Guinea to the west, Mali and Burkina Faso to the north, and Ghana to the east. The country contains 318,000 square kilometers of land, and the 2012 population was estimated to be 20,152,894, growing at annual rate of 2.08%. Forty-nine percent of the population lives in rural areas, and 68% of the labor force works in agriculture. The 2011 GDP was US $24.07 billion, of which agriculture comprised 24%. The most significant export commodities are cocoa, coffee, timber, petroleum, cotton, bananas, pineapples, palm oil and fish (World Bank 2012; GOCI 2012b; CIA 2012).

Côte d’Ivoire, located on the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa, for the most part has a flat to undulating terrain, with hills in the west of the country. Its neighbors are Liberia and Guinea to the west, Mali and Burkina Faso to the north, and Ghana to the east. The country contains 318,000 square kilometers of land, and the 2012 population was estimated to be 20,152,894, growing at annual rate of 2.08%. Forty-nine percent of the population lives in rural areas, and 68% of the labor force works in agriculture. The 2011 GDP was US $24.07 billion, of which agriculture comprised 24%. The most significant export commodities are cocoa, coffee, timber, petroleum, cotton, bananas, pineapples, palm oil and fish (World Bank 2012; GOCI 2012b; CIA 2012).

Côte d’Ivoire has over 60 different linguistic and cultural groups, usually classified as follows: the Akan in the southeast and center; the Krou in the southwest; the Southern Mandé in the west; the Northern Mandé in the northwest; and the Sénoufo/Lobi in the north and northeast. The Baoulé are the largest subgroup in the Akan division, and the Bété are the largest in the Krou division. More than five million foreigners (immigrants from or descendants of immigrants from poorer neighboring countries, especially Burkina Faso) live in Côte d’Ivoire (GOCI 2012b; Badmus 2009).

Nearly 64% of land in Côte d’Ivoire is used for agriculture. Of the country’s total land area, 8.8% is arable, 13.2% has permanent crops, 41.5% permanent meadows and pastures, and 32.8% forest. The country’s agriculture is 98% rainfed and based on traditional, manual, land-extensive swidden practices. The average farm household has ten members, and polygamy is widely practiced. In the forested southern region of the country, cocoa and coffee account for more than two-thirds of the cultivated areas, and dominate the economy. Average farm size in the south is 10–13 hectares, including forest and fallow land. Food crops (maize, rice, yams, groundnuts) and cotton are the main crops of the savannah region in the north, where farms average only 3.5 hectares, reflecting higher labor requirements for the crops grown and the difficulty of attracting seasonal labor (World Bank 2012; IDA 1997; Péatiénan 2003).

Over the last half-century, rapid population growth and expansion of land under cultivation have led to a progressive degradation of natural resources. Extensive low-input, low-output agricultural practices, combined with population growth, have led to large-scale deforestation. Currently, natural forests are being cleared at an annual rate of 0.1%. A network of parks and reserves established since independence occupy 9% of the country’s total land area. Although these areas are “protected,” they are being encroached upon by farmers, particularly in the southwest. The population-dense coastal zones of Côte d’Ivoire, which contain the last remnants of bio-diverse wetlands, are threatened by development pressures. Loss of biodiversity, soil degradation and water pollution are ongoing and serious problems (IDA 1997; FAO 2010).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

For the first 33 years following its 1960 independence from France, Côte d’Ivoire was ruled by authoritarian President Félix Houphouët-Boigny. Envisioning a country of small landholdings producing crops for export, Houphouët-Boigny encouraged both Ivoirians and immigrants to expand Côte d’Ivoire’s agricultural frontier with the clarion call: “The land belongs to those who develop it.” The policy was largely successful for two decades. Côte d’Ivoire became the most prosperous and politically stable country in the region, and by the 1970s it was the largest producer of cocoa in the world, as well as an important producer of the robusta variety of coffee (Badmus 2009; Richards and Chauveau 2007; FAO 2010).

In the 1980s, however, falling cocoa and coffee prices, and fiscal mismanagement by the government led to serious economic setbacks. When unemployed urban youth returned to their home villages to seek their livelihood, they found that most of the productive land was in the hands of farmers who were not native to the area and of a different ethnicity and religion. After Houphouët-Boigny died in 1993, the careful balancing of various ethnic, religious and urban-rural interests began to unravel. President Henri Konan Bédié, Houphouët-Boigny’s designated successor, aggravated tensions by introducing the xenophobic concept of “Ivoirianness” (Ivoirité), i.e., the primacy of indigenous people in relation to people of foreign origin. Bédié was overthrown in a military coup d’état in 1999, and the United States restricted development assistance to Côte d’Ivoire in the same year. In 2000, long-term opposition leader Laurent Gbagbo won election as president, defeating the coup leader who also ran in the election (Peace Direct 2011; Badmus 2009; US Embassy 2012).

Gbagbo was seen as the champion of disaffected autochthones (descendants of the original inhabitants of the area), angry about the state of land distribution in the country. While still in parliament, Gbagbo was the main proponent of the 1998 Rural Land Law, which, reversing Houphouët-Boigny’s land policy, is based on the principle that land belongs to the indigenous people. During Gbagbo’s administration, schisms in society surfaced in a violent fashion and resulted in an armed conflict that from 2002 to 2007 divided the country between a rebel-controlled north and government-controlled south. Gbagbo repeatedly delayed scheduled presidential elections, and when elections finally occurred in late 2010, he lost and refused to step down. Fighting then erupted between forces loyal to Gbagbo – who for the most part represented southern ethnic groups, Christians and defenders of Ivoirité – and forces supporting legitimately-elected Alassane Ouattara – who reflected the new, increasingly Muslim demographic reality of the country. After a few months Gbagbo was defeated militarily and, because of atrocities committed by government troops during the post-election period, he is currently facing crimes-against-humanity charges in the International Criminal Court. President Ouattara, inaugurated in 2011, is a US-educated economist, the first Muslim to lead Côte d’Ivoire, and the son of an immigrant father. He faces a series of daunting challenges, including slow economic growth, a steep decline in foreign investment, mounting debt, degraded infrastructure, widespread poverty and a population still deeply divided (Peace Direct 2011; Crook et al. 2007; Groupe Jeune Afrique 2012).

According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the rural poverty rate in Côte d’Ivoire rose from 15% to 62% between 1985 and 2008. This dramatic increase in poverty is attributed to political upheaval, civil war, and falling prices for the country’s chief exports. FAO poverty estimates come from household surveys of Cote d’Ivoire’s National Statistics Institute. The World Bank’s national poverty rate (combining urban and rural) was 10.1% in 1985 and 42.7% in 2008. Considering that the rural poverty rate is higher than the urban rate, FAO and World Bank figures are consistent (World Bank 2012; World Bank 1997; FAO 2010).

According to the most recent household survey, as of 2008 more than three-quarters of the country’s poor people lived in rural areas. The poorest farm households are in the northern, western and central-western regions. Among the causes cited for the increase in rural poverty are: lack of access to land; destruction of farmers’ production capital; population displacement; marketing problems; low prices for export crops; and dysfunctional social services. There are not large numbers of landless agricultural laborers in Cote d’Ivoire; only 5% of households report that the primary source of income for the head of the household are wages for work on another person’s farm (World Bank 1997; FAO 2010; IDMC 2010).

Child labor is a widespread problem on cocoa and coffee plantations. A Tulane University survey published in 2009 found that 24.1% of children between the ages of five and seventeen in the cocoa-growing regions had worked on a cocoa farm in the previous 12 months. Most worked on family farms or with their parents, but were nevertheless exposed to hazardous conditions. In addition, forced labor by boys from neighboring countries occurred on cocoa, coffee, pineapple and rubber plantations and in the mining sector. In 2011, through a presidential decree, the GOCI created the Joint Ministerial Committee on the Fight against Trafficking, Exploitation and Child Labor to ensure interagency cooperation and to mount an awareness campaign targeted at vulnerable populations (USDOS 2012b; USDOS 2012c).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 2000 Constitution guarantees the right of property to all. From the colonial period until today all vacant and uncultivated land has been deemed to be owned by the state, while occupied land has been effectively governed by customary law systems, a typical feature of which is that land, in a collective fashion, belongs to the lineage of those who first settled and cultivated it. After independence, the Decree of 20 March 1967 stated that “land belongs to the person who brings it into production, provided that exploitation rights have been formally registered.” In practice, the registration requirement was a dead letter. In 1968, the Ministry of the Interior issued a policy directive stating that “all unregistered land is the property of the state,” and “customary rights are nullified.” No action was taken to enforce the directive (Crook et al. 2007; Furth 1998; Stamm 2000; Koudou and Vlosky 1998).

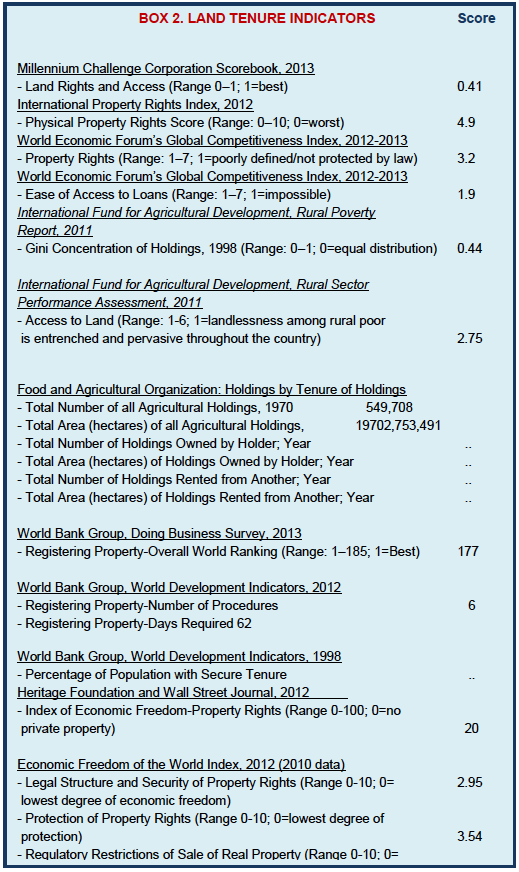

The World Bank-financed Rural Land Plan (Plan Foncier Rural, PFR), initiated in 1989, was the first serious attempt to tackle the thorny problem of land tenure security. The aims of the pilot project were to: survey existing land rights and land use; establish the limits of each plot through investigations carried out at the village level; and develop technically and financially feasible methods for registration of land. The Rural Land Plan and the World Bank-financed Rural Land Management and Community Infrastructure Development Project (Projet National de Gestion des Terroirs et d’Equipement Rural, PNGTER), initiated in 1997, served as the basis for a new legal framework for land tenure in Côte d’Ivoire (World Bank 2011; Zalo 2006; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

The 1998 Rural Land Law (Loi relative au domaine foncier rural, Loi n°98-750 du 23 décembre 1998 modifiée), along with three decrees and 15 implementation orders adopted between 1999 and 2002, aims to enhance land tenure security by transforming customary rights into private property rights regulated by the state. The law breaks new ground by explicitly recognizing customary landholdings, if only during a transitional period. The law provides for an initial ten-year phase subsequent to promulgation (i.e., until January 2009) during which all persons claiming customary land tenure rights (excluding derived rights holders such as tenants) must apply to have their rights officially recognized with a view to obtaining a land certificate (certificat foncier). After the deadline, land not claimed under this process would become property of the state, and those farming it would be deemed to be tenants of the state. In February 2009, the government, in effect acknowledging that virtually no progress had been made in implementing the law, extended the time limit for issuing land certificates by ten years, to January 2019 (GOCI Rural Land Law, Amended1998a; Chauveau 2007; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

Obtaining formal land tenure rights under the 1998 law is a two-step process. The first step is to apply for a land certificate, which confers a transitory type of tenure. The applicant must demonstrate “continuous and peaceful existence of customary rights,” which involves an official investigation at the level of the sub-prefecture in which the claimed plot of land is located. The sub-prefect appoints an investigative commissioner who in turn organizes a public hearing with participation of the village council and the Village Rural Land Management Committee (Comité Villageois de Gestion Foncière Rurale), which includes the traditional land chief, the applicant, occupants of adjoining property and anyone else likely to make a useful contribution. The investigative commissioner publishes the results of the hearing, and during a three-month period any member of the public may register an objection with the prefecture-level Rural Land Management Committee (Comité de Gestion Foncière Rurale). This committee, which is presided over by the sub-prefect and includes community leaders and local representatives of various ministries, can rule on any issues or conflicts left unresolved. If the committee confirms the veracity of the land tenure documentation, a land certificate is signed by the prefect, registered by the local representative of the Ministry of Agriculture and published in the official journal of the prefecture. Land certificates can be held individually or collectively, and land rights described in the certificate may be sold or leased to third parties (GOCI 1999a; GOCI 1999b; Zalo 2006).

In the second step, the certificate holder may apply to obtain either a title deed or emphyteutic lease (a long-term lease by which the lessee has full use and benefit of the land but also an obligation to cultivate it and increase its value in a lasting manner). The application must be submitted within three years of registration of the land certificate. Although the land certificate can be issued to any individual or legal entity (personne physique ou morale), the law provides that only the state, public entities and Ivoirian individuals may become owners. Therefore, if the certificate is held in the name of a collective, such as a village, lineage or family, or if the certificate reflects joint ownership of heirs, these joint holders must decide how they intend to divide the land among themselves and then apply separately to receive the permanent land deeds (titres fonciers) in their individual names. A non-citizen is not eligible to receive a land deed but may obtain an emphyteutic lease (bail emphytéotique) from the private landowner or, if the parcel is registered as state-owned, the same type of lease from the state. All costs connected to registration of land rights, including those for surveying one’s land and certifying one’s rights, are borne by the applicant. These costs and the likelihood of taxes being levied on registered land are disincentives to registration (GOCI 1999a; GOCI 1999b; Stamm 2000; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

Because of the decade-long political crisis, the complexity of the Rural Land Law and the lack of resources devoted to its implementation, only 1172 title deeds and 339 emphyteutic leases have been issued in the entire country. The vast majority of rural land in the country (about 98%) continues to be governed by customary practices (GOCI 2012a; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

With respect to urban areas, the Law on Development Concessions (Loi sur les concessions d’aménagement), adopted in 1997, authorizes the state to grant concessions to land management companies to develop serviced land and housing. The government plans to clear the land titling backlog in order to develop a market for such development (World Bank 2001).

TENURE TYPES

There are two systems of land tenure in the country, customary and statutory. The customary system continues to be dominant, accounting for more than 98% of the rural land of Côte d’Ivoire. Customary rules differ from community to community, but there are basic customary tenure types common to the whole country. The statutory system comes into play only when land is registered, which has thus far been accomplished for less than 2% of rural land. The 1998 Rural Land Law, as modified by decrees, envisions that by 2019 Ivoirians with customary rights to land will register their land and obtain an individual land title. Non-Ivoirians will obtain emphyteutic leases. After 2019, theoretically, the customary land tenure system will disappear (Zalo 2006).

The principal customary forms of land tenure in Côte d’Ivoire are the following:

Rights of permanent use. Permanent use-rights are the birthright of persons descended from the original inhabitants of an area. Such rights pass from generation to generation by patrilineal or matrilineal line, depending on the community. Village chiefs, land chiefs or heads of the lineage manage the land as a collective resource bequeathed from their ancestors and held in trust for future generations. The customary rights of members of the lineage are inalienable and perpetual, but plots may be allocated to persons outside the lineage for their use. This form of tenure is common throughout Côte d’Ivoire (McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

Rights to use and benefit from land. Usufruct rights are rights to land that is owned by another. Migrants from other parts of Côte d’Ivoire and from neighboring countries obtain land from a local guardian (tuteur) whom they reward with token gifts and loyalty or, occasionally, with more substantial payment in the form of cash, product or labor. Much of Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa and coffee is produced by migrants who hold their land in this fashion (McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

Leasehold rights. Individuals granted leasehold rights to a parcel of land must make a formal agreement with the lessor. Lessees are typically required to make regular payments of cash or shares of production to the permanent rightsholder. When the land is not registered, the leasehold rights are customary rights (McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

The principal statutory forms of tenure in Côte d’Ivoire are the following:

Land certificate. Legal persons in possession of a land certificate are allowed a transitory form of tenure under the 1998 Rural Land Law. Within three years following the issuance of the certificate, Ivoirian certificate-holders must apply for a definitive land title. Non-Ivoirians may apply only for an emphyteutic lease. In the meantime, rights under the certificate may be sold or leased (Chauveau 2007).

Freehold rights. Persons holding title to a parcel of land have freehold rights. Only the state, public entities and Ivoirian individuals are eligible to own rural land. A land title may be sold to Ivoirians or passed on to heirs, and the property may be leased, but not sold, to non-Ivoirians or private companies (Chauveau 2007).

Emphyteutic lease. Under the 1998 Rural Land Law, a lease of this kind entitles holders to heritable and alienable tenure rights of 18 to 99 years duration. While lease-holders do not own the land, they own everything built and produced on it. This is the most secure form of tenure available to non-Ivoirians (Chauveau 2007).

In addition, Côte d’Ivoire has privately-owned industrial-scale farms for export crops such as rubber, palm oil, banana, coconut, pineapple and sugar cane. Most of these farms are the result of the privatization of former government-owned development companies set up after independence. Private companies may obtain a land certificate and either transfer it to an Ivoirian citizen or use it to obtain a long-term lease from the state (Richards and Chauveau 2007; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

Many urban-dwellers, because they have no registered title deed, own their houses but not the land on which they stand. Urban land, when not recorded, usually belongs to a traditional local chief or is owned by the government (Gulyani and Connors 2002).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Land in rural Côte d’Ivoire is for the most part attached to the lineage of a specific area’s original inhabitants. Rights of permanent use are regarded as communal, inalienable and perpetual. In many cases land has a spiritual component, and offerings to ancestors and spirits ensure its fertility. Administration and management of land-related issues, most importantly the allocation of plots, is generally in the hands of village chiefs or land chiefs, who are patriarchs of the lineage. Individual families are granted rights to cultivate designated plots, which include fallow areas, and these rights are heritable within the family. Unused lands revert to the community. In patrilineal communities, land is passed from father to son. In matrilineal groups, such as the Akan, land is passed from maternal uncles to their nephews. Under customary land tenure systems, whether patrilineal or matrilineal descent, women have no access to property ownership (Richards and Chauveau 2007; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

Since the 1940s there has been significant migratory movement of people in southern Côte d’Ivoire. Searching for better farmland, the large Baoulé ethnic group from the central southern part of the country and foreigners from Burkina Faso, Mali, Guinea and other nearby countries moved to forested and little-developed parts of the south and west, where they acquired land from the original inhabitants through a system of guardianship (tutorat). This customary practice allows outsiders the full use and enjoyment of a plot of land to cultivate crops and make their homes in exchange for small gifts, gratitude and, occasionally, payment in the form of cash, product or labor. The arrangement, usually made orally, is regarded as permanent and binding on both parties and on their respective descendants. For the autochthones, putting vacant land to use under their guardianship, especially when the plots lie on the fringes of lineage landholdings, protects their hold on the land by marking it out with respect to neighboring villages. For the Ivoirian government, as well as the earlier French colonial authorities, opening the frontier to migrants increased agricultural production, including of the country’s top exports, cocoa and coffee (Richards and Chauveau 2007; McCallin and Montemurro 2009; Chauveau 2000).

During the armed conflict of 2002–2007, many foreign migrants were forced off their land and became internally displaced persons (IDPs) or refugees in neighboring countries. In late 2005 a survey funded by the United Nations Population Fund and conducted by Côte d’Ivoire’s National School of Statistics and Applied Economics (ENSEA) counted almost 710,000 IDPs in five government-held regions. An additional 200,000 persons had fled the country. When IDPs and refugees returned to their farms following the 2007 peace settlement, many found that they were unwelcome and that their plots had been sold (contrary to custom and law) or leased to others. Migrants forced to flee post-election violence in 2010–2011 faced a similar plight. Côte d’Ivoire has not developed a specific system of restitution or compensation for properties abandoned due to conflict. Under the 1998 Rural Land Law, which appears to be the migrants’ only legal recourse to repossess their property, there is a requirement of “a certified statement of the continuous and peaceful existence of customary rights.” The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), an NGO supported by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), notes that it is unclear how this provision will be interpreted with respect to persons who abandoned their land due to armed conflict (McCallin and Montemurro 2009; IDMC 2009; UNCEDAW 2011; Massey 2005; Kolouma 2012).

The relationship between ethnic Fulani (mostly foreign) pastoralists and the sedentary Sénoufo farmers of the savannah region of northern Côte d’Ivoire is in the process of transformation as land available for grazing becomes more scarce, in particular as farmers increasingly turn to tree crops such as mangoes and cashews to boost their income. Traditionally, transhumant pastoralists have been allowed to roam freely over harvested and fallow fields where their cattle grazed crop residues and grass. The land benefitted from the application of manure, and the Fulani herders also sometimes cared for cattle owned by local farmers. As competition for land increases, however, local farmers are beginning to institute grazing fees (Bassett and Koné 2007; Furth 1998).

The Ministry of Construction, Housing, Sanitation and Urban Development (Ministère de la Construction, du Logement, de l’Assainissement et de l’Urbanisme, MCLAU) controls and manages vacant government-owned land in Abidjan and the other major towns of Côte d’Ivoire. It is responsible for the distribution of urban plots, which are converted to private ownership in a phased process. First, during the concession phase, one applies for an award letter, which serves as a provisional and temporary title. The holder of an award letter may not sell or otherwise dispose of the lot in question, but it may be inherited. The second phase requires a technical dossier demonstrating that the lot has the necessary amenities and any construction on it is of standard materials. Because the registration process is lengthy, expensive and bureaucratic, it often is not completed. Many urban-dwellers thus own their houses but not the land on which they stand (GOCI 2012c; Djibril et al. 2012; Gulyani and Connors 2002).

Informal settlements are common in urban and peri-urban areas of Côte d’Ivoire and are usually situated on publicly owned land. In Abidjan, roughly 15–17% of settlements are considered illegal because of their location, the absence of basic services or the substandard construction of the dwellings (Gulyani and Connors 2002).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

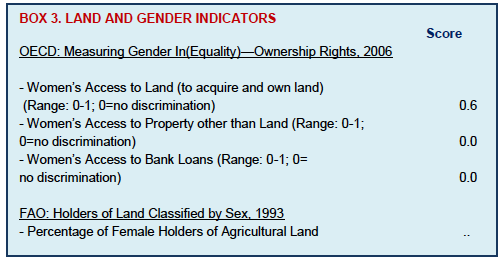

Côte d’Ivoire’s constitution affirms gender equality before the law, as does the 1998 Rural Land Law. The Marital Equality Act of 2012 revised an antiquated section of the Civil Code that made the husband the sole head of the family. Henceforth, husband and wife have joint and equal responsibility for managing the household and raising children. There remain, however, several discriminatory provisions in Ivoirian law. With regard to the right of property, the law gives the husband the authority to administer and dispose of marital assets in a community-property marriage. To avoid this rule, couples can affirmatively choose a separate-property regime at the time they marry, but few do. A 1964 decree banned polygamy and all land succession except patrilineal inheritance, thus denying women the right to pass on land through their blood line. Neither part of the 1964 decree is effectively enforced, however. In 1998, according to UNICEF, 34.8% of women were in polygamous unions. The Minister for Family, Women and Children, reporting to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, pledged that the current government of Côte d’Ivoire will review and eliminate any remaining discriminatory legislation (FIDH 2012; UNCEDAW 2011; IRIN 2012c; OECD 2012).

Côte d’Ivoire’s constitution affirms gender equality before the law, as does the 1998 Rural Land Law. The Marital Equality Act of 2012 revised an antiquated section of the Civil Code that made the husband the sole head of the family. Henceforth, husband and wife have joint and equal responsibility for managing the household and raising children. There remain, however, several discriminatory provisions in Ivoirian law. With regard to the right of property, the law gives the husband the authority to administer and dispose of marital assets in a community-property marriage. To avoid this rule, couples can affirmatively choose a separate-property regime at the time they marry, but few do. A 1964 decree banned polygamy and all land succession except patrilineal inheritance, thus denying women the right to pass on land through their blood line. Neither part of the 1964 decree is effectively enforced, however. In 1998, according to UNICEF, 34.8% of women were in polygamous unions. The Minister for Family, Women and Children, reporting to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, pledged that the current government of Côte d’Ivoire will review and eliminate any remaining discriminatory legislation (FIDH 2012; UNCEDAW 2011; IRIN 2012c; OECD 2012).

Statutes concerning marital property and women’s access to property are of little relevance in rural Côte d’Ivoire as they apply only in the case of legal marriage, which is rare outside major urban centers. Under customary law, a woman’s access to land depends on her relationship to a husband, father, uncle, brother or son and on the goodwill of that male relative. Although women play an essential role in agriculture, producing and marketing 60–80% of the food in Côte d’Ivoire, they have no land ownership rights under customary law, and their access to land is limited. When a woman marries, she works her husband’s land.

If the union is polygamous, each wife receives a plot to cultivate. In the event of the husband’s death, the wife or wives generally remain on the land to protect the interests of their male children. If there are no sons, the brother of the deceased will inherit the land. Most communities allocate plots of land to widows and female orphans who do not otherwise have access to land, but women are generally not allowed to cultivate perennial crops, which are the most profitable. Because women do not produce cash crops like cocoa and coffee and do not possess a title to a house, they are unable to meet the lending criteria established by banks. Some banks also require a husband’s approval before a married woman can secure a loan (OECD 2012; ECA 2004; Richards and Chauveau 2007; FAO 2010).

The 1998 Rural Land Law seeks to erase distinctions between men and women with respect to land ownership rights while at the same time giving recognition to customary land rights, which are held exclusively by men. Because men control land, only they will obtain land certificates under the 1998 law, even if they might hold the certificates on behalf of a collective, such as a family group. Women have the opportunity to claim their portion of a parcel of land when the land is divided into individual plots prior to the issuance of individual title deeds. The outcome of the process depends on members of the collective being informed about and asserting their rights, and on the goodwill of the man who, before redistribution, controlled the collective land. Women, who are generally less educated than men in rural Côte d’Ivoire and less likely to be informed about the law, are at a distinct disadvantage and risk exclusion (FAO 2012b; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Côte d’Ivoire inherited a highly centralized governmental structure from the French colonial administration. After independence and especially in recent years, the government’s policy has been to gradually devolve power to the local level. For administrative purposes, Côte d’Ivoire is now divided into 81 departments, each headed by a prefect appointed by the central government. There are also approximately 1000 communes, each comprising a town, a section of a city or a group of villages, and headed by an elected mayor. Village chiefs, chosen according to customary rules, usually by consensus, manage affairs at the village level (GOCI 2012b; IDA 1997).

The Office of Rural Land and Rural Land Registry (Direction du Foncier Rural et du Cadastre Rural), which is part of the Ministry of Agriculture (Ministère del’’Agriculture), has a presence in every department. Its mission is to give effect to the 1998 Rural Land Law by putting in place a land registry indicating village and plot boundaries, and recording claims to land as well as current land uses. This requires the cooperation of Village Rural Land Management Committees in more than a thousand locations around the country and the demarcation of 24 million hectares of farmland. The task is complicated by the lack of adequate capacity and staffing in the rural land registry, which in 2009 had only 23 land surveyors at its disposal (Zalo 2002; McCallin and Montemurro 2009; IDA 1997).

In 2003 the Prime Minister set up the Joint Ministerial Technical Rural Land Committee (Comité technique interministériel sur le foncier rural) to lead efforts to educate the public and provide training for stakeholders on the provisions of the 1998 Rural Land Law. The committee includes representatives from the Ministry of Agriculture, The Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, the Ministry of Construction, Housing, Sanitation and Urban Development, and the Ministry of Economic Infrastructure, as well as representatives of agricultural producers, financial institutions and the scientific community. The committee, which is also charged with studying the impact of the 1998 law and making proposals to improve the legal framework concerning rural land, has been inoperative because of political upheaval (Zalo 2002; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

Urban land-tenure matters, including the registration of plots, are managed by the Office of Land Development of the Ministry of Construction, Housing, Sanitation and Urban Development. One priority of the ministry is to develop an urban land law along the same lines as the 1998 Rural Land Law and for the same principal purpose: to improve land-tenure security. The Land Management Agency (Agence de Gestion Foncière, AGF) negotiates the acquisition of customary land rights from traditional chiefs and then sells the land to developers. The aim of this public-private partnership is to bring order to the development of Côte d’Ivoire’s cities and town (World Bank 2001; GOCI 2012c).

Corruption impacts all bureaucratic undertakings, contract awards, customs and tax matters, the accountability of the security forces and judicial proceedings. Obtaining an official stamp or copy of a birth certificate, death certificate or automobile title requires payment of a supplemental “commission.” For example, truckers moving cargo from the western agricultural belt to Abidjan typically pay a total of US $100– 400 to pass through the various police checkpoints. Laws and regulations to combat corruption are not effectively enforced (USDOS 2012a; USDOS 2012b; FAO 2010).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

The land market in Côte d’Ivoire is characterized by informality and uncertainty. Less than 2% of land is held under title deed, and land transactions are seldom recorded. Questions frequently arise as to the seller’s legitimacy, the contents of the rights being transferred, and the obligations of the purchaser with respect to the seller. Despite increased demand for land throughout the country, which is fueled by the continued development of cash crops, population growth and immigration, the process for transferring rights to land, even in urban areas, tends to follow custom rather than law (Colin and Ayouz 2006; Koné and Chauveau 1998).

In rural Côte d’Ivoire, newcomers to an area obtain property rights through guardianship arrangements or by purchasing rights from a migrant leaving the area. Rural land transactions thus occur between autochthones and migrants, or between migrants and other migrants (usually when sellers decide to return to their land of origin), but seldom between autochthones. Most such transactions are oral or at best commemorated by a simple receipt or “small papers” (petits papiers) signed in the presence of a village chief or land chief. As Ivoirian law recognizes only land transactions witnessed by a notary and duly registered, these transactions carry no legal weight (Colin and Ayouz 2006; Koné and Chauveau 1998).

The lack of clarity surrounding land transactions gives rise to myriad misunderstandings and conflicts between the parties and between the heirs of both. Customary law does not recognize the “sale” of property; it authorizes only the transfer of usufruct rights, which are accompanied by a complex and ongoing implied system of “payment” from the land user to the guardian in the form of gifts and continued social interdependence. Although such use rights are generally regarded as permanent and heritable as long as obeisance is duly paid, there is a propensity on the part of the heirs of the original landholders to challenge the validity of the transfers or to demand renegotiation of terms (Colin and Ayouz 2006; Chauveau and Colin 2010).

Land leasing has proliferated since the 1990s. Contractual rights that are clearly set out and agreed upon by the parties enjoy a high level of security. In the southeast almost 80% of the land cultivated in pineapple is leased through fixed-rent or share contracts, mostly to Burkinabé farmers who come into the area not to settle but specifically to produce pineapple. The leasing market impacts negatively on the sales market for two reasons: first, landowners prefer not to lose a source of income, and second, the opportunity to lease out mitigates the absence of a credit market and thus reduces distress sales (Richards and Chauveau 2007; Colin and Ayouz 2006; Zalo 2006).

The urban rental market in Côte d’Ivoire is quite developed. In Abidjan about three-quarters of residents are renters. Elsewhere in Côte d’Ivoire the urban rental market is smaller, as in the municipality of Aboisso, where 37% of residents are renters and the rest own their homes (Gulyani and Connors 2002).

In an effort to promote legal certainty in the land market, the government adopted the 1998 Rural Land Law, which regulates land transfers by requiring that property rights be identified and registered. Under this law, on a transitional basis the state recognizes de facto forms of customary landholding to allow those claiming customary rights to apply for the conversion of those rights to a statutory form of tenure; claimants then obtain either a recorded title deed or a recorded long-term lease. Ivoirian legislators, who passed the law unanimously, believe that greater land-tenure security brought about by registration will induce private investments in the land and result in higher levels of productivity as well as more environmentally sustainable farming practices. The law reserves land ownership for Ivoirian citizens, but non-citizens may obtain a heritable and alienable lease of up to 99 years’ duration. However, the law is little known and little used; its full implementation would require the monumental task of demarcating over 24 million hectares of farmland and recording the land rights that attach to each parcel. In 13 years, from 1997 to 2010, the World Bank’s PNGTER resulted in 1.12 million hectares being surveyed (Chauveau 2007; FAO 2010; Zalo 2006; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Article 15 of the 2000 Constitution of Côte d’Ivoire states: “No one shall be deprived of his property unless it is for public benefit and on condition that just and prior compensation is made.” The government uses its power of eminent domain to seize unused land belonging to traditional local chiefs, providing them compensation in the form of lump-sum payments or allocation of one or more serviced plots in a future upgraded area. As of June 2012, the US Embassy in Abidjan was not aware of any cases of illegal government expropriation of private property (GOCI 2000; Djibril et al. 2012; USDOS 2012a).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Land disputes in Côte d’Ivoire were to a large extent both a cause and consequence of the political turmoil that shook the country from 1999 to 2011. As a deteriorating economy compelled young and unemployed urban-dwellers to return to their villages of origin, they found that outsiders had taken control of much of the land that the returnees regarded as family patrimony. Because the relatively prosperous migrant farmers were from different cultures and ethnic groups, and often also had a different religion and nationality, they became victims of a combustible mix of prejudice and resentment. A politically partisan national press fanned the flames by carrying sensational reports of violent confrontations between young autochthones and Ivoirian or foreign migrants, usually in the central-west and southwest. Existing customary and statutory mechanisms to resolve such conflicts fell far short of the task. By 2002, hundreds of thousands of people who had lived peacefully in their communities, sometimes for decades, fled their homes (ECA 2004; Colin and Ayouz 2006; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

While the conflicts of the recent past were unprecedented in their violence, tensions concerning competing land claims are nothing new in Côte d’Ivoire. There is a long history of conflict in the Akan lands of the southeast and between the indigenous groups and Baoulé settlers in the west. In fact, it is estimated that 80% of land conflicts in the country do not involve foreigners. Most disputes arise because land transactions are shrouded in vagueness, and the parties have different understandings as to the contents or duration of their agreement (WANEP 2002).

The vast majority of rural land disputes are mediated by village chiefs or land chiefs. The customary authorities are widely respected and are generally skilled at arriving at a compromise in which each party to the dispute derives some advantage. The goal of the method and the ruling is to limit humiliations or resentments and to maintain social cohesion. The customary process has the advantage of proximity and affordability and, because it is highly participatory and transparent, the community and the parties tend to view the process as legitimate. Nonetheless, a party may feel aggrieved by a ruling and may appeal to the cantonal chief as a superior authority (Crook et al. 2007; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

Alternatively, land disputes may end up on the desks of local administrative authorities, usually a sub-prefect. Migrant farmers in particular may prefer the administrative route because they consider the village chief, normally a scion of one of the area’s original land-owning families, to be inherently biased in favor of autochthones like himself. In addition, younger autochthones may have less respect for customary authority and choose to have their cases mediated by government officials. Sub-prefects, who represent the government in a cluster of villages, prefer that cases be resolved at the village level but generally will step into the breach when necessary (Crook et al. 2007; McCallin and Montemurro 2009).

The courts are seldom used and, if they are, only as a forum of last resort. The judicial system is at best slow, expensive, inefficient and ineffectual; in recent years it simply stopped functioning at all. When the courts were taking cases, the average time from filing to resolution of a contract dispute was eight years, and it was not unusual for a case to be tied up for decades. Moreover, there is a widespread belief that judges are subject to political and financial influence. For these reasons, persons who bring a case to court are viewed with suspicion and are thought to be hostile to accepted community standards (Crook et al. 2007; USDOS 2012a; USDOS 2012b).

Although the basic idea behind the adoption of the 1998 Rural Land Law was to modernize the management of the rural land domain and abolish customary land transactions, in the area of conflict resolution customary practices have proven to be more effective than formal legal mechanisms. In time, as the 1998 law is implemented, the rural land management committees at the village and sub-prefect levels are expected to play a greater role in resolving land disputes, thus weakening the role of traditional authorities (Crook et al. 2007).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Côte d’Ivoire has been attempting to develop its rural areas, the source of the country’s wealth, for more than a century. The main focus since independence has been on decentralization to foster better planning and administration at the local level. In the 1970s the government created rural districts (pays ruraux), groupings of six to nine villages on approximately 300 square kilometers of land, to be the principal planning units in the countryside. In 1995 the government approved a law to allow the rural districts to be governed by locally elected bodies with administrative and financial autonomy (World Bank 2011).

The Ivoirian government recognizes that conflict over land was one of the root causes of the decade-long crisis that tore the country apart. Tenure insecurity continues to discourage rural producers from investing in the land they occupy. Effective implementation of the 1998 Rural Land Law, a process that was stalled by civil unrest, is therefore not only a major part of Côte d’Ivoire’s agricultural strategy but a prerequisite for peace and reconciliation. According to the Director of Rural Land and Rural Land Registry, land tenure security provided by the 1998 law is “a factor in social cohesion inside of villages and between villages and should contribute to reestablishing a climate of confidence and reconciliation between the communities of this country.” Given the economic wreckage left by of years of political tumult, the government looks to the international donor community to finance its land tenure program (World Bank 2011; Zalo 2006).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The World Bank and the French Development Fund (Caisse Française de Développement) funded the Rural Land Plan (PFR, 1989–1996), and the Rural Land Management and Community Infrastructure Development Project (PNGTER, 1997–2010), which together served as the basis for the drafting of the 1998 Rural Land Law and subsequent improvements in Côte d’Ivoire’s land tenure system. The PFR pilot project demonstrated that there exists a strong demand for clarification of land rights. During the course of the project, fieldwork was completed on 495,000 hectares, encompassing 27,300 plots in 360 villages. The US $60.8 million PNGTER involved land surveying and mapping, certification of land rights, and dispute resolution at a time that armed conflict had split the country in two. Of the 2 million hectares targeted, 1.12 million hectares were surveyed and 44,209 village parcels demarcated. In addition, the PNGTER contributed to the establishment of rural land management committees in various parts of the country, and developed the Land Information System (SIF) for computerized management of implementation of the Rural Land Law (World Bank 2011).

The World Bank also funded the US $11 million Urban Land Management and Housing Finance Reform Technical Assistance Project (1997–2002), to help establish a functioning land market in Côte d’Ivoire’s cities and towns. The project was largely responsible for adoption of the Law on Development Concessions and for the creation of the Land Management Agency (AGF) (World Bank 2001).

The other major donor in the area of land tenure security is the European Union (EU), which supports the Office of Rural Land and Rural Land Registry in the Ministry of Agriculture. The (EU) is involved in capacity-building and helping the government to organize a media campaign on the 1998 law (World Bank 2011).

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) has been active in Côte d’Ivoire throughout the crisis years, providing information, counseling and legal assistance to internally displaced persons (IDPs), refugees and returnees. The NRC together with the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) has also furnished comprehensive documentation on land disputes and forced displacement in the country (IDMC 2009; NRC 2012).

In 1999 the United States restricted US development cooperation with Côte d’Ivoire, and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) ended its bilateral presence in the country. Following the inauguration of President Alassane Ouattara in 2011, however, the U.S. Mission launched an interagency transition assistance program with the goal of preparing the government to become eligible for a compact with the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) (US Embassy 2012).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Côte d’Ivoire has about 77 billion cubic meters (or 3971 cubic meters per capita) of renewable fresh water resources, including surface water and groundwater. Surface water sources include rivers, streams, lakes, artificial reservoirs, springs, marshes and lagoons. In addition to several small coastal rivers and tributaries of the Niger and Black Volta, Côte d’Ivoire has four principal river systems: the Cavally, the Sassandra, the Bandama and the Comoé, all flowing south into the Gulf of Guinea. Côte d’Ivoire has 572 dams (mostly erected in the 1960s and 1970s) with a total storage capacity of about 38 cubic kilometers. Many of these manmade reservoirs are now considered lakes, including the Buyo, the Kossou, the Taabo and the Ayamé. Côte d’Ivoire’s groundwater is located in aquifers in sedimentary basins or on top of or in the cracks of crystalline bedrock. To access groundwater, Ivoirians may dig sumps, ponds or wells (FAO 2005; World Bank 2012; Biémi 1996; CIA 2012; Gadji 2003; Aregheore 2009).

Wetlands cover an estimated seven million hectares of Côte d’Ivoire (about 22% of the total land area). Six wetland sites covering 127,344 hectares are designated Wetlands of International Importance. Côte d’Ivoire is the most biologically diverse country in West Africa, and the wetlands provide habitats for hundreds of plant and animal species, including fish, mollusks, crustaceans, reptiles and waterfowl. Several endangered and threatened species live in Côte d’Ivoire’s wetlands and other surface water, including manatees, forest and Nile crocodiles, several species of turtles and pygmy hippopotamuses (FAO 2005; Ramsar 2005; Hance 2011).

In Côte d’Ivoire the average precipitation is 1348 millimeters per year, and rainfall varies by region. The tropical south, including the forest region, has the most abundant and consistent rainfall (about 1500 millimeters annually), with two rainy seasons (March-June and September-November) and two dry seasons (December-March and July-August). The area in the middle of the country also has four seasons and averages between 1200 and 1500 millimeters of precipitation annually, but the rainfall is more erratic, and the area is more susceptible to flooding. The semi-arid savannah in the north has only one rainy season, averages between 900 and 1200 millimeters of rainfall per year and is also susceptible to floods and droughts (FAO 2005; GWP 2012; Gadji 2003; Aregheore 2009; IDA 1997; Duflo and Udry 2003).

Annually, 1.4 billion cubic meters of freshwater are withdrawn, of which agriculture claims 43%, domestic use 38% and industry 19%. Most cultivation completely depends on rainfall, including 90% of rice crops. Only 2% of permanent cropland (or 0.4% of total agricultural land) is equipped for irrigation. Areas that are irrigated generally produce industrial or export crops (World Bank 2012; Duflo and Udry 2003; FAO 2005).

Côte d’Ivoire began developing its hydropower sector in the 1960s. In 2007, Côte d’Ivoire produced about 1800 gigawatt hours of hydroelectricity (33% of its total electricity production). The country’s main hydropower plants are Ayamé I and II, Kossou, Taabo, Buyo and Grah. Côte d’Ivoire exports its surplus energy (about one-third of the electricity generated in 2010) to Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mali and Togo. In order to boost power capacity and extend power export capability to Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone, GOCI will begin construction on a new 270-megawatt hydroelectric system in the Soubré region in 2013. Côte d’Ivoire has identified four other undeveloped hydropower sites (with capacities ranging from five to 288 megawatts) (REEP 2010; USEIA 2012; New Democrat 2013; African Review 2013).

In the early 2000s, 81% of Ivoirians had access to safe drinking water. However, regular maintenance and repair to water infrastructure was neglected during the conflict that ended in 2007, especially in rural areas in the north of the country. Increased urbanization has put additional pressure on the water and sanitation infrastructure. By 2008, 24% of Côte d’Ivoire’s population (and 35% of rural residents) used unsafe sources for drinking water, and 43% of Ivoirians lacked adequate sanitation facilities. Where infrastructure does exist, taps have frequently run dry, and Ivoirians have turned to less safe sources for their water supply. Consequently, Ivoirians (especially women and girls) must spend more of their time fetching water. Risk of waterborne infections and diseases, such as cholera and typhoid fever, has increased (FAO 2005; UNICEF 2008; IRIN 2012a).

Côte d’Ivoire does not currently conduct systematic monitoring of water quality, but increased water pollution from sewage and agricultural and industrial runoff has degraded the water supply. In recent years, the population in urban centers has increased, leading to pressure on sanitation facilities, and sewage being directly discharged into waterways. Economic development efforts have increased the amount of industrial effluents, and the use of chemical fertilizers is increasing chemical runoff. Concentration of pollutants in the water supply is higher in the dry season. Increased seawater contamination of freshwater sources in coastal areas also reduces water quality (N’Guessan 2012; GWP 2012; Groga et al. 2012; AfDB and OECD 2007).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1998 Water Code (Code de l’Eau), established by Law No. 98-755, is the principal piece of legislation governing use of precipitation, surface water, groundwater and territorial seas in Côte d’Ivoire. Under the Water Code, the country’s water resources are part of the common national heritage, and the state provides integrated management of all water resources, facilities and structures. The state’s water priorities are: (1) providing drinking water; (2) protecting, conserving and managing water resources; and (3) satisfying other human water-related needs. The state’s water management duties under the Water Code include: maintaining quality of water resources; preventing waste; ensuring availability; preventing waterborne disease; and developing and protecting water facilities and structures. The government may contract out the operation of water structures and facilities to other entities, as it has for the provision of drinking water (discussed below) (GOCI 1998b).

Under the Water Code, the right to use water is connected to the right to use land. For example, anyone can collect rainwater that falls on their land or use water from a pond on their property without permission from the government. However, certain water-related activities always require government approval, including activities that: interfere with the free flow of surface or groundwater; present a public health or safety danger; interfere with water navigation; degrade the quality or quantity of water; significantly increase the risk of flooding; or present a serious risk to the quality or diversity of the aquatic environment. Use of water for grazing, industry, fishing, transportation or recreation requires an easement (servitude) (GOCI 1998b).

Water users are subject to usage fees set by the state. The state can issue decrees regulating quality standards (including discharge limits), measures of classification and declassification, and management of system utilities. The Water Code also provides a legal framework for water-related law enforcement, offenses and penalties (GOCI 1998b).

The National Agency for Water of Côte d’Ivoire (Agence Nationale de l’Eau de Côte d’Ivoire, or ANECI) has drafted decrees for the implementation of the 1998 Water Code in 2008, 2010 and 2011. However, as of 2012, the GOCI has not passed any implementing decrees. Without an implementing decree, the specifics of how the law works and what its standards are remain unclear (N’Guessan 2012; Mémoué 2012).

The 1996 Environmental Code, established by Law No. 96-766, lays out the legal framework for protection of the environment against pollution and degradation, and contains provisions related to water management (Gadji 2003; FAO 2005).

A hybrid lease contract (affermage) framework underlies the provision of water in Côte d’Ivoire. The contract establishes a long-term arrangement between a private water supply services enterprise and the state, which provides public finance for development of the water supply infrastructure. The state awarded the first concession contract in 1959 to the Urban and Rural Planning Company (Société d’Aménagement Urbain et Rural, or SAUR), a French private water distributor which operates through its Ivoirian subsidiary Côte d’Ivoire Water Distribution Company (Société de Distribution d’Eau de Côte d’Ivoire, or SODECI). The contract covered Abidjan and major cities and was later extended to the entire country. In 1987, the government signed a new 20-year “concession” contract with SODECI, which included changes to key terms. SODECI no longer has responsibilities for rural areas. Instead, the onus to provide water services was transferred to rural communities, although the government continues to provide financing through regional cross-subsidization. Under the new agreement, the GOCI and SODECI established a new Water Development Fund (Fonds de Développement de l’Eau, or FDE) under which SODECI collects a tariff surcharge from connected customers and manages the fund for network extension and subsidized household connections. The contract provides for tariff revisions every five years, but this process was delayed during the conflict. Consequently, in recent years SODECI has not collected enough to keep up with maintenance costs (Tremolet et al. 2002; Fall et al. 2009; Foster and Pushak 2010).

Côte d’Ivoire is a member of the Niger Basin Authority and the Volta Basin Authority, intergovernmental organizations that foster cooperation in managing and developing the resources of the Niger River Basin and Volta River Basin, respectively. Côte d’Ivoire also ratified the Convention on Wetlands, an intergovernmental treaty committing members to protect and sustainably use wetlands (GOCI 1998b; ABN 2012; Modern Ghana 2006; Ramsar 2005).

TENURE ISSUES

The state has classified water consumption into five different categories (social, domestic, normal, industrial and administrative), and charges fees at different rates based on each category. Fees go into the National Water Fund (FNE) and Water Development Fund (FDE) for the operation, maintenance and new development of the water systems (AfDB and OECD 2007).

Drinking water supply is provided to Ivoirians though urban water systems, village water systems and improved village water systems. In order to access water supply services, households in urban areas need legal rights to the places where they live. SODECI operates the urban water system, including the treatment, distribution and billing of drinking water in towns and cities. About half of Côte d’Ivoire’s urban population is connected to the potable water system via individual connections or standpipes. In order for households to receive water services, they must allow SODECI to install water meters. This requirement poses problems for those residing in illegal settlements, which in Abidjan are home to 15–17% of the population. Illegal settlements occupy areas that are either unfit for development or slated by the government for other uses. Because they have no rights to the land and SODECI cannot install water meters, squatters in the illegal settlements lack access to water services. They also lack the means to pay for formalizing their land tenure to make access to water possible. Even where households have a sound legal basis for claiming rights to land, many low-income households lack access to water services because they cannot afford the cost of connecting their house to the water system, and also lack documentation of their land rights, which is needed to receive a government subsidy for water services (AfDB and OECD 2007; Collignon et al. 2000; Kariuki et al. 2003; Gulyani and Connors 2002).

In urban areas, increasing population and infrastructure that was damaged or fell into disrepair during the conflict have put pressure on the safe drinking water supply. Many taps are broken, leading urban dwellers to purchase potable water from informal water vendors. The informal market in water makes people vulnerable to price hikes and distribution of unsafe or illegally obtained water. SODECI has accused informal water vendors of illicitly siphoning water out of SODECI’s pipes at night (Kouassi 2011; Kouassi 2012).

Village water systems rely on wells and boreholes that access groundwater for potable water supply. In 1990, the GOCI introduced an improved village water system, which provided standpipes for potable water in villages that met certain criteria. In rural areas, the conflict has led to contamination of wells and a high breakdown rate of water supply systems. As a result, rural inhabitants seek water elsewhere, potentially from unsafe sources, increasing their risk of waterborne infections (AfDB and OECD 2007; Sapienza 2011).

IDPs, who numbered 710,000 in 2005, also lack access to safe water. Although the political crisis ended in 2011, social tensions continue to prevent IDPs from returning home. This population is doubly affected. Not only do IDPs require access to water in a context where the socio-political crisis has severely impaired water infrastructures, but they must manage this challenge while being displaced from or barred from accessing their original water access points (IDMC 2009; IDMC 2010).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

In 2011, the GOCI created the Ministry of Water and Forests (Ministère des Eaux et Forêts, or MINEF). The Directorate of Water Resources (Direction des Ressources en Eau, or DRE) within MINEF is responsible for implementing the Water Code. MINEF must also work with the ministries in charge of economic infrastructure, environment, agriculture, health and animal resources and fisheries to ensure integrated management of Cote d’Ivoire’s water resources (GOCI 2012d).

Historically, the GOCI’s water management system involved many different institutions. The multitude of actors and fragmented activities led to an uncoordinated approach to water management. In 1996, the GOCI created the High Commission on Water (Haut Commissariat à l’Hydraulique, or HCH) to lead water policy reform and coordination. In June 2012, the HCH approved the National Action Plan for Integrated Management of Water Resources (Plan d’Actions National de Gestion Intégrée de Ressources en Eau, or PLANGIRE), which further reforms the institutional framework on water management. The goal of PLANGIRE is to achieve water security and environmental sustainability through 2040, and implementation is expected to cost 20 billion CFA (about US $40 million) (N’Guessan 2012).

The new framework under PLANGIRE provides for institutions at four levels: national, basin, regional/departmental and local. Each level will have four categories of stakeholders: (1) public administration; (2) territorial or local communities; (3) basin organizations; and (4) other actors such as users, the private sector and NGOs. DRE’s responsibilities under PLANGIRE will include: monitoring implementation of the Water Code; coordinating the implementation of PLANGIRE; monitoring international conventions and agreements for water resources; promoting, supporting and monitoring projects and programs of national and international watershed organizations; promoting education, research and development in the field of water; developing a financial policy in conjunction with the Department of Administrative and Financial Affairs; developing a water policy; overseeing sub-national agencies and structures; and protecting water resources (N’Guessan 2012).

The National Drinking Water Authority (Office National de l’Eau Potable, or ONEP) guarantees access to safe drinking water for the people of Côte d’Ivoire. It also manages public and private assets related to the potable water sector. The financial resources of ONEP are provided by the FNE and FDE (GOCI 2011).

The GOCI created National Village Water Point Management Units (Cellules Nationales de Gestion des Point d’Eau Villageois, or CNGPEVs) to help rural communities manage hydrological works, and to increase women’s empowerment by including women on the CNGPEVs (GOCI 2012e; Nouveau Réveil 2012).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Under the Poverty Reduction Strategy, Cote d’Ivoire made several improvements to the water sector in the period from 2009 to 2011. These interventions derive from the commitment to ensure access to safe water and increase the percentage of people with access to safe drinking water in rural, suburban and urban areas. In 2009, the government began professionalizing the administration and operations of rural hydraulic structures. During 2009 and 2010, over a thousand rural wells were drilled and several water infrastructure repairs and improvements made. The government also established the Presidential Emergency Program in 2011 to improve infrastructure that had worsened following the post-electoral crisis. Between 2009 and 2011, ONEP also began to professionalize water management in suburban areas and to install new infrastructure. In urban areas, the government joined with development partners to upgrade twenty water treatment stations (GOCI 2012e).

In 2005, the Ministry of Agriculture conducted a study on irrigation potential and developed a national irrigation plan that provides for a US$1.7 billion investment to rehabilitate 3000 irrigated hectares and irrigate an additional 139,000 hectares. The Ministry of Agriculture acknowledged in the study that the benefits from the improved irrigation network depend on the development of feeder roads in addition to the irrigation infrastructure itself (Foster and Pushak 2010).

From 2005 through 2008, the GOCI, as a member of the intergovernmental Niger Basin Authority (Autorité du Bassin du Niger, or ABN), participated in the Niger-Hydrological Cycle Observing System (Niger-HYCOS) project, which aimed to collect data on water heights and flows in the Niger River Basin. During this first phase, the ABN installed two data collection platforms in Côte d’Ivoire. In 2011, the GOCI and ABN signed an agreement for implementation of Phase Two of the project (GOCI 2012e; WHYCOS 2007).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

During the 2002–2007 armed conflict in Côte d’Ivoire, much of the water infrastructure was damaged or fell into disrepair due to insufficient maintenance, leading to a lack of access to safe drinking water. Donors have addressed this issue with projects to repair water infrastructure and improve local water management. In 2009, United Nations agencies spent US $56.9 million to support basic social services, including water and sanitation. In 2006 and 2007, the United Nations Childrens’ Fund (UNICEF) repaired over 2000 village pumps and re-started over 1800 water management village committees. In 2011, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) began treating wells with chlorine and rehabilitating village water pumps to ensure that local populations could access safe drinking water. In 2011, UNICEF and its project partners researched the failure of 200 manual pumps and restarted 100 water point management committees to provide water to over 100,000 IDP returnees in the Moyen Cavally region.

Between 2009 and 2011, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) has provided water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) assistance to ninety villages throughout Cote d’Ivoire, and chlorinated wells and distributed water purification tablets in the Nahibly IDP camp1. During that same period, Oxfam provided WASH assistance as well (UNICEF 2008; UNDP 2012; GOCI 2012e).

Five hydro-agricultural projects are being implemented in Cote d’Ivoire in 2012. These include the rehabilitation of eighteen irrigated areas covering over 400 hectares in the North, along with creation and rehabilitation of irrigation infrastructure in M’bahiakro (450 hectares) and the N’zi Valley (130 hectares). These projects are co-funded by the GOCI, the West African Development Bank, the Kuwait Fund, the Islamic Development Bank and the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (GOCI 2012e).

In 2002, the African Development Bank (AfDB) approved a US $33.7 million grant to improve agricultural infrastructure in Cote d’Ivoire, although the project has been delayed due to the conflict. In addition to other agriculture-related infrastructure improvements, the project activities include rehabilitating irrigation infrastructure of 923 hectares of land, constructing forty boreholes and installing seven improved village water systems and 100 hand pumps. The project began in 2012 and is expected to involve 9000 smallholder farms and benefit over 100,000 inhabitants (ADF 2012).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION