Published / Updated: August 2010

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

In Guatemala, a history of discrimination and inequality of opportunity led to a 36-year conflict that finally subsided with a Peace Agreement in 1996. Improvements since then have prevented a return to conflict and begun to create the conditions for sustained stability. However, the persistence of substantial inequality constitutes a risk factor for future stability and constrains Guatemala’s growth potential.

Land distribution is highly unequal. The largest 2.5% of farms occupy nearly two-thirds of agricultural land while 90% of the farms are on only one-sixth of the agricultural land. Furthermore, tenure is insecure and is one of the key causes of poverty among indigenous Guatemalans, who make up 43% of the population. Multiple unresolved land disputes and ineffective mechanisms to resolve them discourage investment and reduce the potential contribution of agriculture to improvements in rural living standards and overall economic growth.

Guatemala’s extensive and biologically diverse forest systems are experiencing a rapid 1.3% annual rate of deforestation and losing their economic value due to forest fires, agricultural expansion, wildlife-poaching, and large-scale development projects. Increases in ongoing donor assistance to empower communities in resource management of this valuable forest system would help Guatemala achieve a greater, more sustainable yield from its forests and reduce the rate of deforestation.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

Guatemala still lacks a basic land law that describes basic tenure types and addresses indigenous rights to land. These shortcomings make it difficult to resolve land conflicts, and leave the indigenous population without the means to obtain legal certainty regarding their interests and rights to land. Women are prevented from enjoying legal rights to land and are insecure in their access due to patriarchal customs and attitudes. Donors should support a Guatemalan review of the legal framework governing land, including family law, and provide recommendations for a basic land law and other laws that can reduce tenure insecurity, particularly among the indigenous population and women. The legal framework around land should explicitly support communal property rights and other ownership systems that are traditional in indigenous communities. Donors should consider recommending to Guatemala the development of a National Land Policy to inform drafting of such a land law.

The Government of Guatemala (GOG) should assess FONTIERRA’s past performance and institutional capacity, to inform recommendations for improving upon its delivery of pro-poor services and for improving transparency and accountability. It should also consider revisions to the land purchase program to include micro-plots for the landless and other programs to decrease the number of landless. households.

Donors and the government should support national and local institutions (both formal and informal) in their efforts to resolve land disputes, including family law courts and indigenous systems and methods of resolution in order to improve those institutions’ knowledge of the law, as well as the accessibility, functionality, efficiency, and coordination of the institutions. This effort could include training on land rights and conflict-resolution methods as well as developing a land-rights curriculum for the law schools, and piloting a rural legal aid program that engages and trains local residents to serve as paralegals in rural communities.

Donors should consider support for implementation of a public information and awareness campaign on the existence and importance of land rights of the rural poor as well as indigenous populations, with an emphasis on women’s land rights.

There is no national policy or law governing the use and protection of water resources; this lack perpetuates an environment where the resource is poorly managed and conserved. Donors could support a Guatemalan review of the legal framework governing water resources, and assist in conducting an assessment of water use and protection to inform recommendations for a basic national water policy and law and the governmental agency charged with implementation.

Too little is being done to maintain the rich biodiversity and long-term sustainability of Guatemala’s forestry resources. This reduces forests’ potential to contribute to improved livelihoods and sustainable economic growth. Donors should continue support of forestry and livelihood initiatives, including support for the Maya Biosphere Reserve. Donors should also assist the GOG to assess impacts of extraction and reforestation concessions to determine if such concessions are ensuring sustainable forest management.

Donors could support the reformation of the current Mining Law to include environmental and human rights protections. They could additionally support the reformation of the current royalty scheme to ensure that a percentage of mining profits is invested in local communities. Finally, donors could encourage compliance to Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO) on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries to ensure that local populations are consulted prior to mineral exploration or exploitation.

Summary

Guatemala has a history of rural poverty, distorted land distribution patterns, and severe income inequality. Land-related issues were a fundamental cause of the 36-year Guatemalan Civil War, which ended in 1996. The Peace Accords attempted to address land issues, including access for the poor, legal reform, and land administration. However, political will for reform has been limited, and Guatemala continues to have the most inequitable and concentrated distribution of land ownership in Central America.

Land conflicts are a major issue in Guatemala. Observers have noted that the country’s economic development and competitiveness will be stunted until land conflicts are addressed. Although widespread violence in the near future is unlikely, land disputes could lead to political instability.

Indigenous and peasant populations face systemic exclusion from access to land. Tenure insecurity is one of the key causes of poverty among these groups. The rural population comprises 52% of the total population, of which 80% is indigenous. Three-quarters of the rural population live in poverty, which correlates with their geographic isolation and ethnic exclusion.

Indigenous and peasant populations face systemic exclusion from access to land. Tenure insecurity is one of the key causes of poverty among these groups. The rural population comprises 52% of the total population, of which 80% is indigenous. Three-quarters of the rural population live in poverty, which correlates with their geographic isolation and ethnic exclusion.

The Guatemalan Civil War and resulting human rights abuses led to the displacement of between 500,000 and 1.5 million people. Many of these internally displaced persons (IDPs) moved to informal squatter settlements in and near Guatemala City. Guatemala’s over 200 informal settlements are characterized by inadequate housing and hazardous living conditions. Twenty-three percent of children living in these settlements suffer from malnutrition.

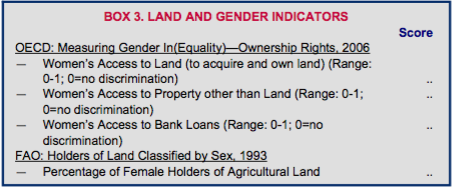

Although there are no legal restrictions on women’s access and rights to land, the percentage of female landowners is extremely low due to prevailing patriarchal influences. Within indigenous communities, women are even more marginalized. Women-headed households, particularly those headed by indigenous women, are more susceptible to poverty.

Guatemala is rich in water resources, primarily from streams and lakes. However, surface water is unevenly distributed, seasonal and often polluted. Water resources are stressed by growing demand, deforestation and agricultural pressure. Contamination by biological and chemical agents occurs in varying degrees throughout the country. This problem is compounded by the limited capacity of sewage systems in urban centers; raw effluent flows directly into the streams.

Guatemala has one of the most extensive and biologically diverse forest systems in Central America. Some 2.8 million hectares of forest are protected under the Guatemalan Protected Areas System. The Maya Biosphere Reserve, the largest protected area in Mesoamerica, is threatened by forest fires, unsustainable agricultural expansion, poaching, and poorly planned large-scale development projects. These threats have resulted in rapid deforestation.

Mineral exploration and exploitation is contentious in Guatemala. Mining Laws encourage investment in the mineral sector, but do not offer strong environmental or human rights protections. Local communities near mining projects have allegedly had their property forcibly expropriated, been compensated below the market value of their land, and have been made ill as a result of the chemicals used in the mining process.

Land

LAND USE

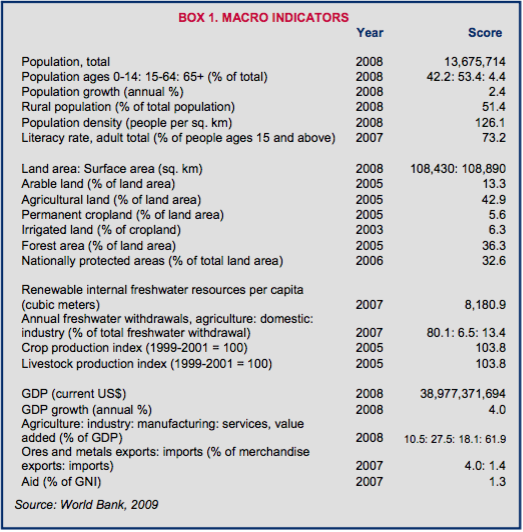

Guatemala’s total land area is 109 thousand square kilometers with a 2008 population of 14 million. Of total land area, 43% is agricultural land and 36% is forested. Thirteen percent of the land is arable and 24% is pasture land. The rural population comprises 51% of the total population, of which 80% is indigenous. Three-quarters of all rural people live in poverty, which correlates with their geographic isolation and ethnic exclusion (SID 2004; World Bank 2009a; FAO 2004; WFP 2005).

Guatemala’s 2008 GDP was US $39 billion, consisting of 61% services, 11% agriculture and 28% industry. Agriculture continues to play an important role in the Guatemalan economy. The sector employs approximately two-thirds of the working population and produces 50% of total export earnings (World Bank 2009a; WFP 2005).

Six percent of cropland is irrigated and used for cash and export crops, mainly vegetables and sugar cane. Primary agricultural products are sugar, fruits and vegetables, and cereals (World Bank 2009a; FAO 2004).

Six percent of cropland is irrigated and used for cash and export crops, mainly vegetables and sugar cane. Primary agricultural products are sugar, fruits and vegetables, and cereals (World Bank 2009a; FAO 2004).

Guatemala has over 200 informal squatter settlements, many of which are located in and around Guatemala City. These settlements are characterized by inadequate housing, hazardous living conditions and increasing gang violence. Twenty-three percent of children living in these settlements suffer from malnutrition. Women-headed households, particularly those headed by indigenous women, are more susceptible to poverty (COHRE 2002; Cabanas Diaz et al. 2000; IDMC 2009; IFPRI 2002; UN-Habitat 2010).

Guatemala has become a staging point for the flow of illegal drugs into North America. Drugs are trafficked through El Petén and by boat off the country’s Pacific coast. El Petén is a largely unpopulated region where drug traffickers utilize crude landing strips to transfer drugs. Guatemalan security forces lack the capacity to deal effectively with the incursion of drug traffickers (Johnson 2009).

Demand for natural resources has strained forests, water and soil. Deforestation is occurring at a high annual rate, primarily due to demand for firewood. Watersheds have deteriorated. Soil degradation and erosion are severe (World Bank 2008a; SID 2004).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Guatemala has the most inequitable and concentrated distribution of land ownership in Central America. Historical and pervasive inequality in land distribution was a fundamental contributor to the country’s 36-year civil war and continues to be a primary cause of rural poverty. The government’s attempts to redistribute land between 1951 and 1954 were short-lived. A military coup in 1954 ended and reversed the redistribution; the new government returned land rights to previous owners at an average holding size of 3000 hectares. Currently, 2.5% of farms occupy 65% of the land, while 88% of farms occupy 16% of agricultural land (USAID 2005b; Lastarria-Cornhiel 2004; Deininger 2003; FAO 1999).

A long-standing landed oligarchy controls vast tracts of productive land and maintains political influence over land and labor issues. The highest levels of land concentration are in departments with the most fertile land. In contrast, subsistence farmers cultivate small parcels on increasingly eroded hillsides, primarily in the Western Highlands. In impoverished regions such as the western and northwestern departments, farm parcels range from .5 to 2 hectares (1.2 to 5 acres) per family. These departments also have the highest density of indigenous populations, as well as the highest rates of poverty and social marginalization in the country. Most food-insecure villages are almost entirely indigenous. Guatemala has the third-highest level of malnutrition in the world (USAID 2005a; Lastarria-Cornhiel 2004; SID 2004; WFP 2005; World Bank 2007).

Indigenous Guatemalans face systemic exclusion from access to land. During colonization, the Spanish expropriated indigenous lands to create plantations, and forced the population onto ever-smaller plots at higher elevations. The Spanish engaged the indigenous population as workers on the plantations or as tribute payers on communal lands. This land policy continued for 50 years after independence, when communal land was converted to private property through low-priced sales. As a result, many indigenous people became workers on coffee plantations. Until the mid-twentieth century, government administrations worked to dispossess indigenous groups of their land. Currently, 40% of the economically active population is landless; indigenous populations are overrepresented within this group (USAID 2005b; Gould 2006; Ybarra 2008).

A United Nations Special Rapporteur has cautioned that access and rights to land are one of the fundamental problems facing the indigenous population, and particularly indigenous women. The issue is a cause of increasing social tensions (IDMC 2009).

The Guatemalan Civil War and resulting human rights abuses led to the displacement of between 500,000 and 1.5 million people. These internally displaced persons (IDPs) were dispersed across the country. IDPs are among Guatemala’s poorest residents and are vulnerable to food insecurity and malnutrition (IDMC 2009).

As of 2007, 2.6 million people – or 40% of the urban population – lived in slums. In Guatemala City, slum and non-slum households share neighborhoods on the urban periphery, the dilapidated city center, and in “slum islands” that are located amidst more affluent, fully serviced areas. The Gini Coefficient for urban areas at the national level is 0.55, which is the highest in Central America (2005 data) (UN-Habitat 2010).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1985 Political Constitution of the Republic of Guatemala, as amended in 1993, recognizes the right to private property. The Constitution makes the state responsible for providing indigenous communities with state lands necessary to their development. Implementation of this provision has been limited (ILC 2003; World Bank 2006b).

Guatemala does not have a clear, integrated agrarian policy or land law. The 1973 Civil Code provides general principles on possession, use, transfer (through inheritance, mortgage, lease, usufruct or purchase/sale) and ownership rights over real property, including land and its registration (USAID 2005b; World Bank 2006b; GOG 1973).

Rules for registering land rights are set forth in specific legislation dating from 2005 back to 1880, as well as in the Civil Code. The 1999 Land Fund Act, or FONTIERRAS Law, and its 2005 implementing regulations create a program to facilitate access to land by individuals, including campesino (peasant) individuals and communities. The 2005 Cadastral Information Registry (RIC) Law provides a detailed process for establishing and maintaining the cadastre. The 2002 Municipal Code provides for municipalities’ cadastral responsibilities, including establishing and maintaining municipal cadastres through the municipal planning office. The Code also provides a procedure for resolving land disputes involving a municipality. The 1880 Law of Supplementary Titles allows for the acquisition and ownership of land via a series of administrative steps without requiring proof of continued occupation of the land. This law has been heavily criticized for the lack of checks confirming that the land is vacant and for ignoring the rights of Mayan communities (World Bank 2007; World Bank 2006b; Amnesty 2006b).

The 1948 Expropriation Law governs matters related to the state’s power of compulsory acquisition over land and other property. The 1998 Foreign Investment Law also addresses expropriation (GLG 2010; Rodriguez 2006).

The State’s Real Estate Property Adjudication, Sale or Usufruct Law governs the state’s transfer of real estate rights to people with low income and wealth levels (GLG 2010).

The 1964 Law of Family Courts governs a range of family matters including common law marriage, divorce and inheritance. Family Courts have jurisdiction over all matters relating to the family (GLIN 1999b).

There is no uniform customary law governing land. Rather, customary law varies among communities and ethnic groups (World Bank 2006b).

TENURE TYPES

The1985 Constitution, as amended (1993), recognizes the right to private property and states that every person may dispose freely of their property, in accordance with the law (World Bank 2006b; GOG 1985, Art. 39).

Guatemala lacks a basic land law identifying specific tenure types, although, in practice, several tenure types exist, including private ownership, communal, use (colonato/usufrutco), leasehold, municipal, and state (government above municipalities) (World Bank 2006b).

Under the 2005 RIC Law, communal lands include those in property, possession or tenancy of indigenous or peasant communities as collective entities with or without legal title. In some areas, common ownership has evolved into individual ownership. However, many owners do not have formal title to their land (World Bank 2006b; Macours 2009).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

In Guatemala, land is typically secured through inheritance, purchase, lease, use, administrative fiat, and government programs (Lastarria-Cornhiel 2004).

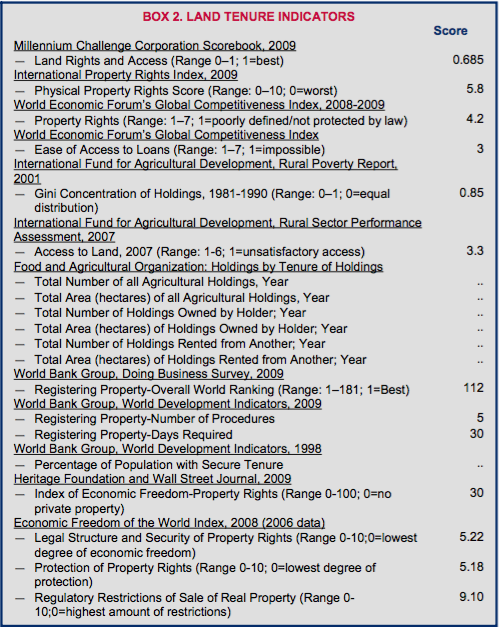

As of 1998, 30% of the country’s properties were registered, though the majority of registered properties were located in urban areas. In contrast, 95% of rural parcels were not registered. The GOG and the World Bank plan to title 50% of the country by 2013. The 2005 Cadastral Information Registry (RIC) Law provides a detailed process for establishing and maintaining the cadastre (World Bank 2007; World Bank 2006b).

Guatemala has yet to adopt procedures for registration of communal land. The Civil Code states that land held communally by more than one owner will be registered in the name of one of the owners only. In some cases, indigenous groups have registered land rights as municipal property; in most cases they have not registered their communal rights at all. Either approach leaves these groups vulnerable to competing claims by private individuals or entities. In the context of large-scale titling projects, such as that funded by the World Bank in El Peten, traditional Q’eqchi’ Maya communal tenure patterns have in some cases been converted into individual privatized parcels (Lastarria-Cornheil 2004; GOG 1973; Ybarra 2008).

Under the 1880 Law of Supplementary Titles, a person may acquire rights to land without proof of continued occupation. A person must report the parcel as vacant to the appropriate authority. The claim then goes through a series of steps to determine whether the land is actually vacant. This process has been criticized for its lack of checks confirming that the land is vacant and for ignoring the land rights of the indigenous, who rely on customary law and have often lived on land for generations, but lack formal legal title. The Peace Accords called for the suspension of grants of titles under this law, but between 2000 and 2003 there were 8852 supplementary title claims (Amnesty 2006b).

Under the 1973 Civil Code, possession of land may be transferred to ownership after ten years. However, few campesinos are aware of this provision in the law (Bailliet 2002; GOG 1973).

A GOG land-purchase program, FONTIERRAS, provided a means of acquiring land. FONTIERRAS facilitated access to land by individuals and communities through means of low-interest loans. However, the land-purchase program portion of FONTIERRAS has been suspended (World Bank 2007; World Bank 2006b).

Tenure insecurity continues to be one of the primary causes of poverty among the indigenous and peasant populations. Land policy between the 1960s and 1990s made access to formal property rights difficult for indigenous people. Some individuals were able to obtain title through state agencies, but many more gave up or did not attempt to obtain title (World Bank 2006b; Gould 2006).

Tenure in informal settlements is very insecure. Forced evictions, sometimes violent, have been common. The largest informal settlement in Guatemala, El Mezquital, was founded through a large land invasion in the 1980s. A recent UN-Habitat report suggests that the Guatemalan government may be moving toward a policy of slum improvement (COHRE 2002; Cabanas Diaz et al. 2000; UN-Habitat 2010).

Foreigners have the same rights of use, benefit and ownership of property as Guatemalans. However, foreigners may not own land adjacent to rivers, oceans, or international borders (USDOS 2008).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Guatemala has made great progress in establishing gender equity within its legal framework governing women’s access and rights to land. The Constitution recognizes the equality of all human beings and the Civil Code provides for marriage settlements and distribution of marital property under the following regimes: absolute community of property, absolute separation of property, community of acquisitions, and subsidiary regime and property of each spouse. The 1999 Land Fund Act (FONTIERRAS) provides for co-ownership of land for married couples or couples in de facto unions, and individual ownership for single women. The Civil Code provides that all property passed in intestacy be divided equally among relevant heirs, without gender preference (ActionAid 2005; Martindale- Hubbell 2007; GOG 1973, Art. 4).

Guatemala has made great progress in establishing gender equity within its legal framework governing women’s access and rights to land. The Constitution recognizes the equality of all human beings and the Civil Code provides for marriage settlements and distribution of marital property under the following regimes: absolute community of property, absolute separation of property, community of acquisitions, and subsidiary regime and property of each spouse. The 1999 Land Fund Act (FONTIERRAS) provides for co-ownership of land for married couples or couples in de facto unions, and individual ownership for single women. The Civil Code provides that all property passed in intestacy be divided equally among relevant heirs, without gender preference (ActionAid 2005; Martindale- Hubbell 2007; GOG 1973, Art. 4).

Although the Constitution and Civil Code recognize the concept of dual-headed households, there is a low incidence of joint land-registration among spouses (ActionAid 2005).

In practice, only 6.5% of agricultural land in Guatemala is administered by women. The prevailing patriarchal culture influences customs and attitudes. For example, women are often excluded from inheriting land, and in most families the male head of household makes all major decisions concerning land-use. Widows and single women with dependents control land that they have inherited through their father or deceased spouse. Most other women access land through a male relative. Within indigenous communities, women are even more marginalized by their male relatives and are restricted from accessing land through purchase or inheritance (FOCAL 2006; ActionAid 2005; UN-Habitat 1999; Amnesty 2006a; World Bank 2006b).

Few Guatemalan women have taken part in the Government’s agrarian reform programs, and gender disaggregated data is difficult to find. For example, within the FONTIERRA land-purchase program, there is no explicit requirement for jointly titling land. The program focuses on family farming and on household heads, who typically are not women (ActionAid 2005).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The General Property Registry is an autonomous agency that records rights to land. The General Property Registry is now incorporated into the Administrative and Financial System (Sistema Administrativo y Financiero) and coordinates with the Registry of Cadastral Information. There is one central Registry in Guatemala City and one in Quetzaltenango (World Bank 2007; World Bank 2006b).

The Registry of Cadastral Information (RIC) is a cadastre agency responsible for the management of each parcel’s physical and legal information. It also is an autonomous government institution with a board of directors presided over by Minister of Agriculture. The National Geographic Institute (IGN) is at the center of the mapping efforts (World Bank 2006b).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

The land market in Guatemala has been unable to erode the concentrated land ownership structure. Large farms, or fincas, tend to not be subdivided and instead are purchased and sold only among those with wealth or access to the limited available credit. Without the help of a governmental land-purchase program, it is almost impossible for peasants to enter the land market due to lack of sufficient savings to purchase large tracts of land (Schweigert 2006; Viscidi 2004).

There are five steps to registering the sale of a parcel: (1) seller obtains a certificate at the Property Registry to verify the status of the property; (2) seller obtains the cadastral value of the property from the municipality where the property is located or if the municipality does not have a registry, from the Directorate of Cadastre and Real Estate Appraisal (Direccíon de Catastro y Avalúo de Bienes Inmuebles) (DICABI); (3) lawyer/notary prepares and notarizes the sale agreement and the public deed; (4) public deed is delivered to the Property Registry for recording; (5) the municipality and/or the DICABI is notified of the transaction. This process takes approximately 30 days and costs 1% of the value of the property (World Bank 2008b).

The rental market is limited and highly imperfect. There are land rentals to campesinos, but these are temporary and insecure. Landowners perceive a risk to their property rights in granting long-term leases to campesinos. As such, sharecrop tenants do not practice intensive cultivation on large holdings (Schweigert 2006).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The Constitution provides for compulsory acquisition in cases of collective use, social benefit or public interest, provided compensation at the actual value is paid within 10 years. These provisions are codified and expanded upon in the Expropriation Law and the Foreign Investment Law, but are not clearly defined (Rodríguez 2006).

Article 12 of the Expropriation Law establishes the method for valuing expropriated property. First, the parties may jointly agree on compensation. Alternatively, if the parties fail to reach agreement, expert assessors determine the actual value of the property being expropriated. Whether actual value is equivalent to fair market value is unclear, a fact which has led to criticism of the law for failing to guarantee adequate compensation (Rodríguez 2006; HG.org 2007).

The government of Guatemala has a history of forcefully evicting poor people where land rights are not clear. In these cases, the government has seldom attempted to clarify the rights or compensate evictees. Historic expropriations of indigenous land by the government have negatively impacted land-use, smallholder self-sufficiency, and food security (Amnesty 2006c; COHRE 2002; Wittman and Saldivar-Tanaka 2006; Johnston n.d.).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Land conflicts were a fundamental cause of Guatemala’s civil war, which lasted from the early 1960s until the Peace Agreement was signed in 1996. During the conflict, an estimated 130,000 – 200,000 people were killed; 50,000 were disappeared; 100,000 became refugees; one million were internally displaced; and 200,000 children were orphaned. Land conflicts continue to be a problem in the country. Escalation of these disputes and involvement of state police forces have, in some instances, resulted in death (USAID 2005b; IDMC 2009; LRAN 2007; Amnesty 2009).

Guatemala continues to have an overwhelming number of land disputes. The number of active disputes registered with the state agency responsible for dispute resolution, the Presidential Commission for Legal Assistance and Resolution of Land Conflicts (CONTIERRA) was very high. However, CONTIERRA has been suspended and its functions transferred to the Land Affairs Secretariat (SAA) (Secretaria de Asuntos Agrarios). There appear to be significantly more disputes that are latent and/or have not been registered. Observers have noted that the country’s economic development and competitiveness will be stunted until land conflicts are addressed (USAID 2005b; USBCIS 2002).

Land disputes are particularly complicated because many, if not most, have root causes that date back over 100 years. There are three broad categories of land disputes: (1) disputes over competing property rights and perceptions of property rights (64%); (2) disputes caused by the occupation of property legally owned by another (16%); and (3) boundary disputes (14%) (USAID 2005b).

The first category tends to be between individuals or communities, or between individuals and communities. The state is also sometimes involved as a party. These disputes relate to land titles, private documents, use or possession of land, historically grounded land claims, or government legislation (e.g., environmental). Some are grounded in mismanagement, corruption, confusion, or discrimination within the land titling or property registry agencies (USAID 2005b).

The second category is usually between landless campesino groups and private landowners. These involve relatively recent land occupations (since 2002), and are strategic initiatives to draw attention to the campesino groups’ land needs or to address outstanding labor concerns. This category is prevalent in the north but also in other parts of the country (USAID 2005b).

The third type of dispute relates to boundaries, and is between individuals and communities or between townships and departments. Those boundary disputes that are between indigenous communities and townships can involve significant violence (USAID 2005b).

Key institutions addressing land disputes were all created or re-structured within the context of the negotiations leading up to the Peace Accords. Political will to address land-related matters has been consistently lacking. The Land Affairs Secretariat (SAA), housed within the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, is the state agency responsible for resolving land disputes primarily through the provision of free legal advice and reconciliation. CONTIERRA, the former agency responsible for dispute resolution, was perceived as credible and legitimate although there were significant limitations on its ability to carry out its mandate, including a substantial lack of resources (USAID 2005b; World Bank 2007).

Civil courts are and will remain of limited use in resolving land conflicts because they are slow, inefficient, overburdened, inaccessible, and lack rules of evidence and expertise. Courts are also perceived as lacking neutrality on land issues. Although the Peace Accords contemplated the creation of specific land courts, none yet exist (USAID 2005b).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

In addition to FONTIERRA, the Land Affairs Secretariat (which replaced CONTIERRA) and the GOG’s partnership with the World Bank for land administration (discussed below), the government of President Colom has created a Rural Development Council. The Council, with a budget of US $79.8 million, is charged with promoting projects to increase agricultural productivity. The program is financed by the Agricultural Ministry and Banrural (a banking organization serving mainly rural Guatemala) and, among other functions, provides small farmers with land, a loan, a subsidy for fertilizers and pesticides, and maize seeds. This project will cover 125 municipalities and help farmers most in need (World Bank 2008a).

The Joint Commission on Indigenous Land Rights, a commission of government and indigenous representatives, was created to propose legal and administrative reforms relating to indigenous land rights. In 1999, the commission successfully created the Land Fund (Ley del Fondo de Tierras), which is responsible for the development and implementation of national land policy (ILO 2009; World Bank 2006b).

The 1996 Peace Accords and the 2005 Macro Law of the Peace Accords include land-related commitments to establish a decentralized cadastral-based land registry, a Cadastral Agency, a Land Fund, a land conflict resolution mechanism, and an agrarian jurisdiction. All but the last of these, the meaning of which is unclear, have been created (World Bank 2006b).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

USAID programs in Guatemala have resulted in land title being issued to more than 25,000 farmers in former conflict areas and the resolution of over 300 land conflicts. USAID funded advertisements and workshops in support of amending the Constitution to formalize the Peace Accords, thus ensuring that the Peace Accords will be applicable to future governments. USAID has also developed programs designed to strengthen the legitimacy of legal and political institutions, including the courts. These initiatives include the establishment of conciliation centers in Quezaltenango, Retalhuleu and Zacapa (USAID n.d.; Bailliet 2002).

The World Bank, with USAID and the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ), has undertaken two significant land administration projects. The first was a US $35 million project to increase legal security of land tenure in El Petén Department, an administrative area that includes about one-third of the country. Approximately 3.3% of the population lives in Petén. Project objectives included: (1) passage of a law modernizing land rights in El Petén (such a law would presumably streamline the process for granting and registering individual land rights through the Land Fund); (2) passage of a law establishing a cadastral institutional framework and formalizing cadastral procedures; (3) establishment of an integrated institutional structure between the cadastre and registry; and (4) resolution of land conflicts by CONTIERRA. Project accomplishments include: passage of the Land Fund Law and the Cadastral Information Registry Law, a foundation for increasing legal security of land tenure; integration of registry and cadastral services; establishment of a fully functioning Registry office in El Petén; and the opening of three new regional branch offices of CONTIERRA. The project ended in 2007 (World Bank 2007; Bailliet 2002).

The World Bank’s Land Administration project in El Petén also implemented a communications campaign and publicized project events to enable women to have greater access to information about their rights. Project staff made special efforts to ensure that women benefited from project activities, and to monitor project impacts. At the close of the project, 39% of titles issued by the project were issued to women as heads of household. Longer-term effects of the project are not clear. One study indicated that soon after people received title to their land, they sold it due to outside pressures and threats of violence (ActionAid 2005; World Bank 2007; Ybarra 2008).

The second World Bank project, Land Administration II, is a US $64 million project to increase the legal security of land tenure in seven additional departments and one municipality. Indigenous people account for about 64% of the population of the project area, which constitutes about 22% of the country. The project consists of four components: (1) carrying out the cadastral and limited land regularization processes in the project area; (2) developing the framework at the national and municipal levels to support the field surveys to keep cadastral information updated and incorporate it into initiatives for local development and territorial planning; (3) improving the legal framework for land administration in Guatemala and strengthening the institutional capacity of the agencies involved in its application; and (4) covering the costs of the project coordination unit and evaluation and monitoring systems (including participatory evaluation mechanisms, independent evaluations and audits, and inter-institutional coordination activities). At the conclusion of this project in 2013, approximately 50% of the country will have been covered by updated cadastral services (World Bank 2006a; World Bank 2007; World Bank 2008a).

Other donors financed related projects focusing on increasing the security of land tenure, including the provision of cadastral services in other departments. Those include: GTZ (US $1.3m); the Netherlands (US $6.9m); Norway (US $4.1m); Spain (US $0.6m); Sweden (US $2.2m); and Switzerland (US $7.6m) (World Bank 2007).

The Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) supported advocacy efforts around the Cadastral Information Registry Law, the preparation of proposals of the Rural Development Law, and the Integral Agrarian Reform. The proposed Rural Development Law is not yet in place and is under debate. SIDA also supports seven local organizations focused on promoting the indigenous justice system as a complement to the national justice system (SIDA 2008).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Guatemala is rich in water resources, primarily from streams and lakes. However, surface water is unevenly distributed, seasonal, and often polluted. Where water availability is low, the population is dense. The opposite is true where water is abundant (USACE 2000).

Guatemala has three drainage basins that capture the country’s significant streams. The Pacific Basin is the smallest, occupying 25% of the country. Guatemala’s longest stream, Rio Motagua, drains into the Caribbean Sea Basin, which occupies 35% of the country. The Gulf of Mexico Basin is the largest in Guatemala, occupying 40% of the country. This basin drains the northwestern part of the country and is home to Embalse Chixoy, Guatemala’s largest reservoir (USACE 2000).

The country has around 20 lakes, five of which are significant. These are Lago de Izabal, the largest lake in Guatemala; El Golfete; Lago de Atitlan; Lago Peten Itza; and Lago de Amatitlan. Lago de Amatitlan is located 20 kilometers south of Guatemala City, and receives half of the city’s domestic and industrial runoff. Because it is so polluted, Amatitlan is considered a dead lake (USACE 2000).

Water use is divided among the agricultural (80%), industrial (13%), and domestic (7%) sectors. Surface water supplies about 70% of the public’s needs in urban areas and 90% in rural areas. Both surface and groundwater sources meet industrial and commercial needs. Demand from the agricultural sector is met by surface water sources but will eventually have to shift to groundwater due to decreasing supply of surface resources (USACE 2000; FAO 2004).

Ninety-eight percent of the urban population and 88% of the rural population have access to an improved water source. Improved water sources include household connections, public standpipes, boreholes, protected dug wells, protected springs, and rainwater collection (UNESCO 2006a).

Water resources are stressed by growing demand. Deforestation and agricultural pressure on marginal farmlands have accelerated soil erosion, which degrades the water quality of Guatemala’s streams. Contamination by biological and chemical agents occurs in varying degrees throughout the country. This problem is compounded by the limited capacity of sewage systems in urban centers; raw effluents flow directly into the streams (USACE 2000).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution defines all water as inalienable, non-forfeitable assets in the public domain. The use of water for purposes of development must be in the service of the community and not any private person. The use of water, rivers, and lakes for agriculture and other industries contributing to the development of the national economy is the right of the public and no one particular person. The Constitution also calls for a general water law to regulate the water sector (GOG 1985, Art. 127).

Guatemala does not have a national policy or law governing water resources, although there have been negotiations over a draft law for over 20 years. Legal treatment of water-related issues is addressed somewhat throughout the civil, penal, labor, health, and municipal codes. In the absence of a national law, some municipalities have adopted their own policies and codes (USACE 2000; Global Water n.d.).

Under Article 68 of the Municipal Code Law, municipalities are responsible for the provision of potable water, sanitation and other public services (Water for People 2007).

TENURE ISSUES

Guatemalan laws surrounding water-use are contradictory and often confusing. Under the Constitution, water is in the public domain. However, the Civil Code recognizes water as private property. Other laws treat the resource as public or private, depending on the ownership of the land on which the water is located (GOG 1985; Castagnino 2006; Siglo XXI 2003).

Construction of the Chixoy Dam in the 1980s led to the violent displacement of approximately 3500 indigenous residents. According to some reports, many of those displaced have yet to be adequately compensated for loss of land, including loss of access to communal lands, and losses due to downstream flooding (Johnston n.d.; Aguirre 2004).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

No permanent national water authority exists for water supply. Many other governmental agencies and organizations administer potable water supply and sanitation services (USACE 2000).

The National Commission of Coordination of Water Resources (CONAGUA) is a temporary institution created by Governmental Agreement Number 19-2005. CONAGUA is responsible for the promotion and coordination of the National Water Policy, including the development of general water use and handling regulations and regulatory policies (Water for People 2007).

The Institute of Municipal Development (INFOM) supports municipal governments in providing infrastructure and public services. In 1997, INFOM was charged with the implementation of water sector policies (Water for People 2007).

In coordination with the municipalities, the Ministry of Public Health and Assistance (MSPAS) is responsible for overseeing and regulating water quality and service delivery. Additionally, MSPAS develops sanitation norms (Water for People 2007; USACE 2000).

Municipalities administer public services, including water services. Each of Guatemala’s 333 municipalities is responsible for supplying water and for maintaining water quality. Most Guatemalan municipalities have weak administrative, technical and human resource capacity (Water for People 2007; USACE 2000).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The World Bank financed a US $50 million Second Social Investment Fund (1998–2003), of which 14% was dedicated to improving water and sanitation. According to the World Bank, the project improved the water sector infrastructure and improved women’s access to water (World Bank 2004).

The provision of water supplies has been a common development effort by donors and NGOs alike. Examples have included construction of small irrigation systems, capture of water from streams in the highlands with distribution to nearby communities, and the drilling of wells and capturing of springs in rural areas (USACE 2000).

The UNESCO-IHE Institute of Water Education is implementing a project called Training and Development for the Integrated Management of the Water Resources in the West of Guatemala. The purpose of the project is to coordinate the many interests involved in Guatemala’s water management (UNESCO 2006b).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Guatemala has one of the most extensive and biologically diverse forest systems in Central America. Approximately 36.3% of Guatemala’s area is forested, reduced from 65% in 1950. The forest sector contributed 2.7% of Guatemala’s 2001 GDP. In 2000, the sector generated 37,000 jobs which employed 1.1% of the economically active population. Of Guatemala’s forested land, 38% is privately owned, 34% is nationally owned, 23% is municipal, and 5% lacks clear ownership rights due to conflicts or encroachment (World Bank 2009a; FAO 2006; FAO 2008; Gibson and Lehoucq 2003; Stoian and Rodas 2006).

Ninety-five percent of forest products are used for domestic purposes, primarily for fuelwood and charcoal. The remaining 5% is used by the forest industry. In past decades, development and settlement policies contributed heavily to deforestation. Deforestation occurs at an annual rate of 1.3%. Deforestation is due to demand from the domestic sector and the expansion of agricultural lands. Until 1995, the GOG encouraged the conversion of forests into agricultural land (World Bank 2009a; FAO 2008; CEPF 2004).

Guatemala has protected 23% of its total land area, including 32% of its forests. Some 2.8 million hectares of forest are protected under the Guatemalan Protected Areas System, with 2.1 million hectares of this area belonging to the Maya and Sierra de las Minas Biosphere Reserves. Guatemala’s vast lowland tropical forests are located primarily in the northern part of the country, home to the multi-use Maya Biosphere Reserve (MBR), which was established in 1990 to protect approximately 16,000 square kilometers of Guatemalan forests. The MBR, the largest protected area in Mesoamerica, is home to more than 95 species of mammals and 400 species of birds (World Bank 2009a; WRI 2003; FAO 2008; WCS 2010).

The Maya Biosphere Reserve faces many threats, including forest fires, unsustainable agricultural expansion, wildlife-poaching, and poorly planned large-scale development projects. These forces combined result in rapid deforestation. Secondary threats include inadequate conservation policy and funding at the local and regional levels (WCS 2010).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The legal framework governing forests includes the 1996 Forestry Law (Decree 101- 96) and the Protected Areas Law, as amended (Ferroukhi and Echeverria 2003).

The 1996 Forestry Law declares reforestation and forest conservation a national emergency and emphasizes collaboration with municipal governments. It establishes the National Institute of Forests (INAB), with the responsibility for administering and managing the country’s forestry resources. The law governs: concessions for extraction and reforestation; protection of forests; forest management; projects for forest repopulation; the creation of a private fund to support reforestation; right of cutting forests; the National Forest Registry; crimes committed against forests; and other relevant matters. Municipal governments are required to collaborate with state forest administration and are authorized to manage forests, including developing, approving, and implementing plans for local forest resources (GLIN 1999a; Ferroukhi and Echeverría 2003).

The Forestry Law requires concession contracts to include a resource management plan, part of which should be an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) (GOG 1996, Art 30).

In addition to the Forestry Law, the following laws also touch upon municipal management of forests: the Municipal Code, the Law on Environmental Protection and Improvement, and the Protected Areas Law (Ferroukhi and Echeverría 2003).

The 1996 Peace Accords recognized the need to strengthen community participation in state management by decentralizing public administration and strengthening municipal government (Ferroukhi and Echeverria 2003).

TENURE ISSUES

Ownership of forests is linked to that of the land, except when the land title specifies otherwise. Forests are located on state, municipal, communal, and private lands, and within protected areas (Ferroukhi and Echeverría 2003; GOG 1973).

State-owned forests constitute 34% of total forest area. Over 90% of the national forests are in the Maya Biosphere Reserve in the department of El Petén. The National Forest Institute is responsible for administering and managing these forests; municipalities have no authority over them (Stoian and Rodas 2006; Ferroukhi and Echeverría 2003).

Municipal forests are on municipal lands and are administered by the municipal government. Municipalities lease these lands to residents for agricultural purposes (Ferroukhi and Echeverría 2003).

Community groups administer communal forests and decide norms based on custom. Sometimes municipalities will transfer responsibility for use and management of municipal forests to the community via local agreements or involve co-management (Ferroukhi and Echeverría 2003).

Private forests constitute 38% of total forest area. Forests on private land belong to the owners. Many privately owned forests have been cleared for grazing or coffee-cultivation. Corporations use private forests for wood production (Stoian and Road 2006; Ferroukhi and Echeverría 2003; Gibson et al. 2002; Thunberg 2009).

Forests on protected land can be within any of the categories above. Because they are within the boundaries of protected areas, their use is limited. The National Council of Protected Areas (CONAP) determines the standards and grants use-permits (Ferroukhi and Echeverría 2003).

In response to public pressure, the government now supports concession contracts for both industry and communities in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Northern Peten, in recognition of the fact that private logging concessions had been managing forests poorly. Community concessions allow for the use and management of both timber and non-timber forest products (unlike the industrial concessions). The concessions grant rights to use, withdraw, manage and exclude. The rights to withdraw and manage have strict guidelines although exclusion rights are at times in conflict with other laws (Larson et al. 2009).

Insecure tenure contributes to deforestation and limited investment in resource management. Many farmers, especially those in politically sensitive areas, do not possess legal title to their land, and therefore have little incentive to invest in resource management or in expelling outsiders who enter to exploit the forest (CEPF 2004).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The National Institute of Forests (INAB) has jurisdiction over forests that are not in protected areas. INAB is an autonomous, decentralized independent agency with offices in nine regions and 31 sub-regions. INAB’s Board of Directors is composed of representatives from the Ministry of Public Finances, the National Association of Municipal Governments (ANAM), universities, the Central National Agriculture School, the Forest Guild, and the Association of Non-governmental Organizations Linked to Natural Resources and the Environment (ASOREMA). The Board is coordinated by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food. By Decree No. 101- 96, municipal governments also have responsibility for forest administration (FAO 2008; Ferroukhi and Echeverría 2003).

The National Council of Protected Areas (CONAP) is responsible for managing protected areas, including forests on protected lands. CONAP sets use-norms and issues exploitation permits (Ferroukhi and Echeverría 2003).

There are 16 Community Forest Enterprises (CFEs) (2006 data). Eleven of these are organized under FORESCOM (Forest Services Community Business, or Empresa Forestal Comunitaria de Servicios del Bosque S.A.), which provides CFEs with technical and business services. FORESCOM is a community forestry business focused on balancing the protection of ecosystems with economic development through concessions. CFEs seek to provide their members with social benefits, employment opportunities and dividends (Stoian and Rodas 2006; USAID 2009).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID has invested $38.6 million into the Maya Biosphere Reserve since 1990, with approximately $8 million going toward a program that preserves the forest and helps farmers living in the area to make a living legally, through the forestry community concessions. Among other activities, assistance has also included focusing on creating a community concession-granting mechanism and empowering communities through the formation of associations that link with local NGOs to manage the forest (USAID 2005a).

USAID supports subsistence farmers in generating income while maintaining the forest. The program teaches farmers about forest management, product certification and marketing, and financial management. Farmers also learn how harvesting and marketing forest products from a healthy forest generates increased and sustainable income (USAID n.d.).

The World Bank funds the Regional Strategic Program for Management of Forest Ecosystems (PERFOR). PERFOR (2008–2012) is designed to improve forest management in Central America, including Guatemala (World Bank 2009b).

The FAO is providing US $300,000 to the Guatemalan National Institute of Forests for reforestation of mangrove forests in Ocós, San Marcos. The mangroves are in serious danger of extinction due to uncontrolled cutting of trees and the deterioration of the environment where they grow (Guatemalan Times 2009).

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

The mineral industry contributes about 3% of Guatemala’s GDP. The only mineral of global significance is antimony, comprising 1% of the world’s production. Guatemala also produces limited crude petroleum. Other minerals include basalt, feldspar, gold, nickel, cobalt, and silver (Anderson 2008).

The development of the extractive industries has been characterized by weak governance, and is tightly controlled by powerful elite. In Guatemala, mining companies can be 100% foreign-owned. By 2005, the GOG had granted over 115 new licenses to foreign mining companies, bringing the total to over 200 potential operations, nine- tenths of which were in the indigenous territories of the Highland (Holt-Gimenez 2008).

An open-pit gold mine, Marlin, is the subject of significant controversy. The Canadian company Goldcorp owns the mine, which was partially financed by a US $45 million loan from the International Finance Corporation (IFC). Indigenous, environmental, human rights, and church organizations at the local, national, and international levels charge that the mine threatens indigenous rights to water and food, and the repressive measures used against communities’ protests of the mine have led to violations of political and civil rights. The IFC found that the mine was in compliance with human rights requirements, though the assessment has been dismissed by international human rights organizations. In May 2010 the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, an autonomous organ of the Organization of American States (OAS), called for the Marlin Mine to shut while the Commission investigates allegations of human rights abuses and environmental damage. The Commission issued precautionary measures for 18 communities near the mine. The Commission regards its recommendations as binding on member countries (McBain-Haas and Bickel 2005; CAO 2006; MarketWatch 2010; Globe Investor 2010).

As of June 2010, the GOG reportedly suspended new mining projects pending the adoption of new mining legislation that strengthens environmental protections (Josephs 2010).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1997 Mining Law codifies the constitutional grant of ownership of subsurface resources to the State. Excluded from its scope are petroleum and liquid and gaseous hydrogen carbides. The Law requires license applicants to submit either environmental mitigation studies that establish a work plan to reduce the potential environmental impact, or environmental impact studies. The 1997 law was adopted to increase foreign investment in the mining industry. It removed limits on foreign ownership, decreased taxes and set royalty rates at 1% of production volume; royalties are shared between the state and the affected municipality. The royalty rate is low by international standards and has been widely criticized (GOG 1997; Castagnino 2006; Roca 2006; Amuchastegui 2007; Valladares 2009).

In 2008, a new Parliamentary Commission on Energy and Mines (PCEM) opened debate on reforming the current Mining Law to be more sensitive to environmental impacts and human rights. Also in 2008, the Guatemalan Constitutional Court ruled eight articles of the Mining Law to be unconstitutional. These included Article 75, which permitted mining corporations to release tailings-contaminated water directly into surface water (COPAE 2008; MRGI 2008).

The Organic Law for Deposits of Petroleum and Petroleum Products (1991) governs rights to explore and exploit petroleum resources (Martindale-Hubbell 2007).

Several Guatemalan laws, such as the Decentralization Law (Art. 18), the Law on Urban and Rural Development Councils (Art. 2), and the Municipal Code (Arts. 35 & 65) guarantee that local populations have the right to consultations. However, the Guatemalan Constitutional Court ruled in 2007 that the community referendum process (held in over 20 mining-affected municipalities in the past five years) is not legally binding (McBain- Haas and Bickel 2005; MRGI 2008).

As a signatory to the International Labor Organization (ILO)’s Convention 169 on Indigenous Peoples and Tribals in Independent Countries, the GOG agreed that it will establish mechanisms for consulting local populations before permitting any exploration or exploitation activities. That commitment is codified in the Municipal Code, the Urban and Rural Development Councils Act, and the Decentralization Act. The ILO has recommended that the GOG implement consultation practices in line with Convention 169. As such, the ILO has called on the GOG to suspend mining operations at the Marlin Mine to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the social, economic and environmental impact of the operation on local populations (Castagnino 2006; OXFAM 2010).

TENURE ISSUES

The Constitution declares the technical and rational exploitation of minerals to be a public necessity. The State is the owner of subsoil resources and regulates their exploration, use and sale. The Mining Law states that the GOG is the owner of all mineral deposits within the Republic of Guatemala (Castagnino 2006; GOG 1997).

Any individual person or corporation, whether national or foreign, may hold rights for reconnaissance, exploration, or exploitation of mineral resources upon the grant of exclusive licenses by the Ministry of Energy and Mines. Mining companies may be 100% foreign-owned (GOG 1997; McBain-Haas and Bickel 2005).

Mining rights are inheritable. The heirs to the mining right must register the ownership of the right with the Registry Department of the Ministry of the Directorate (GOG 1997).

Since the approval of 1997 Mining Law, mining companies pay a royalty of only 1%, they are entitled to use all the water they need without having to pay for it, and they benefit from the easy approval mechanisms of the Environmental Impact Assessments that are required to start the construction and exploitation of a mine. The previous mining law required payment of 6% royalties (COPAE 2008; GOG 1997; Holt-Gimenez 2008).

Disputes have arisen in some cases between companies holding mining licenses and long-time residents of the land. Several of these involve nickel-mining companies, such as the Canadian-owned Guatemalan Nickel Co. which, together with state police and armed forces, reportedly evicted 400 families from land upon which they claimed to have lived for generations in El Estor, Izabal in 2007 (COHRE 2007; Amnesty 2009).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Energy and Mines is the governmental body charged with development of policies and plans for the mining sector. The Ministry grants mining permits, monitors compliance, and issues fines or orders suspension of operations. The Ministry operates through the General Directorate of Mining, which will also regulate such licenses (GOG 1997; Castagnino 2006).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) disbursed a US $45 million loan to the Marlin gold mine project, discussed above. In an assessment of the Marlin Mine operation, the IFC found that the project was in compliance with human rights requirements. However, this finding has been disputed by international human rights organizations (CAO 2006; McBain-Haas and Bickel 2005; MarketWatch 2010; Globe Investor 2010).