Published / Updated: February 2017

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

In December 2009, the Kenyan Parliament approved the National Land Policy (NLP), which calls for an extensive overhaul of current policies and institutions to address chronic land tenure insecurity and inequity. It mandates land restitution or resettlement for those who have been dispossessed and calls for reconsideration of constitutional protection for the property rights of those who obtained their land irregularly. The policy reasserts customary land tenure rights and repudiates the focus on converting customary tenure into individual ownership. The NLP is supported by the Constitution of Kenya adopted in August 2010.

Since 2010, the Government of Kenya (GOK) has made significant structural changes and economic reforms that have contributed to economic growth and stability. The Constitution ushered in a new governance system that has been transformative and strengthened accountability and public service delivery at local levels. County governments have made considerable progress in implementing constitutional and legal provisions for transparency and accountability, and set up structures (websites, communication frameworks and forums) to facilitate public participation. The GOK has promulgated a new suite of legislation in the land, water, forest and mineral subsectors aimed at broadening and securing property rights of Kenya’s citizens.

The Government’s agenda is to deepen devolution, strengthen governance institutions, advance real land reform, promote a more equitable distribution of resources, and reduce extreme poverty and youth unemployment. With the increased competitiveness of its manufacturing sector, Kenya is emerging as one of Africa’s key growth centers and is poised to become one of the fastest growing economies in East Africa (World Bank 2015a and 2015b).

Despite these advancements, weak budgets, lack of administrative capacity and sometimes token participation continue to hinder effective citizen engagement. Land tenure reforms still lack traction in redressing historical injustices. Land related conflict continues in Kenya’s land, water and forest sub-sectors. Land conflict is particularly evident in land takings for public and private sector investment. Chronic water scarcity is contributing to violent conflict in drought-stricken areas while conservation programs and pastoralists compete for land and water resources near parks and protected areas. Kenya’s forests are threatened by encroachment and logging for charcoal and fuelwood. The degradation of critical resource areas, such as the Mau Forest Complex, negatively affects Kenya’s parks and wildlife reserves, which are the foundation of the country’s important tourism industry.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

The majority of slum-dwellers are rent-paying tenants without tenure security. There is acute housing shortage due to under-investment in low to middle-cost housing, an outdated legal and regulatory framework, and high cost of finance. Donors should support a property rights regime that encourages home or apartment ownership, formalizes leases, encourages low cost lending, and clarifies and enforces landlord-renter rights and obligations. They should further assist in developing a land information system that broadly informs the public of real estate offerings and prices, increases the security of transactions, and cracks down on speculation.

Land distribution is skewed by well-documented illegal appropriations of public land by elites during the 1980s and 1990s. The NLP and Constitution include key principles on redressing these illegal acquisitions. Cases are being brought to the courts for redress, and public takings are being increasingly scrutinized. Donors should provide support where needed with land inventorying, informing citizens of due process, negotiating return of assets to rightful owners, advocacy and caseload management, and with formal and informal conflict and dispute resolution.

Kenya in the past decade has taken great strides to overhaul colonial legislation. While more legal reform lies ahead, the emphasis will switch from drafting law to implementing regulations. The legal framework in urban contexts is complex and difficult to understand or enforce. Donors should assist with support for consultation, legal drafting, assessments, advocacy, impact monitoring in an effort to simplify and harmonize the legal framework and help people understand new laws and regulations, with a goal of improving tenure security.

The land registry system makes it difficult to access land cadaster information; the system is still manual and highly centralized. Multiple registrations of single plots of land are common while the slow pace of land transactions encourages extra-legal payments. Donors should continue to help modernize Kenya’s land registries at a central level, extending outward to country level land record offices that require support with equipment, land record management, computerization, and capacity building. They should further support efforts to document and map communally owned land.

Constitutional reforms and development of progressive property, marriage and succession legislation have the potential to address gender discrimination. But only time will tell whether the current body of legislation will be successful in curbing discriminatory practices against women, and how the courts will apply the legislation in practice. While current law treats daughters and sons equally, women rarely inherit land, and inherited property or ancestral land is excluded from matrimonial property. Donors should assist legal reform, public information and awareness, legal aid, and advocacy that empower women’s groups and public defenders to ensure that law is acted upon in ways that tangibly secure women’s land and resource rights.

The Constitution commits to safe and sufficient water as a basic human right; this will require governors and county leadership to drive reforms and decentralization, increase the role of well-performing water companies, expand financing for water service provision, and facilitate citizen participation. The Forests Policy 2014 emphasizes community participation in forestry management including the recognition of user rights, strengthening community forestry associations, and introducing benefit-sharing arrangements. New mineral legislation places the onus on newly established county governments to promote sustainable governance and benefit sharing in the oil and extractive industries. Donors should assist government in ongoing efforts to devolve authority to newly formed county governments, formulate regulations, build new partnerships, leverage private sector capital, engage communities in participatory management, ensure that benefit sharing is achieved and compensation is paid, and champion technical schools to train local youth in skills for the water, forest and oil sectors. They should further strengthen the capacity of county governments to undertake these massive reforms and change the way business is done consistent with the 2010 Constitutional mandate.

Addressing historical land inequities and acquiring land for investment and infrastructure will require difficult and time consuming efforts to balance the interests of Kenya’s investors, communities and citizens for the public good. Facilitating beneficial land investment is difficult in an environment where historical injustices have undermined trust and generated conflict. Donors should assist in promoting full and transparent information, facilitating fair negotiations between investors and landholding individuals and groups, developing contracts that are pro-poor and pro-investment, paying fair and adequate compensation for land takings, and providing due recourse for those affected in disagreements or disputes.

Summary

Land and politics have long been entwined in Kenya. Insecure land rights and inequitable access to land and natural resources contributed to the 2007 election related violence. This violence, in part, reflected grievances related to decades of corruption in the land sector, forced evictions and use of land as an object of patronage to engender support and consolidate political power.

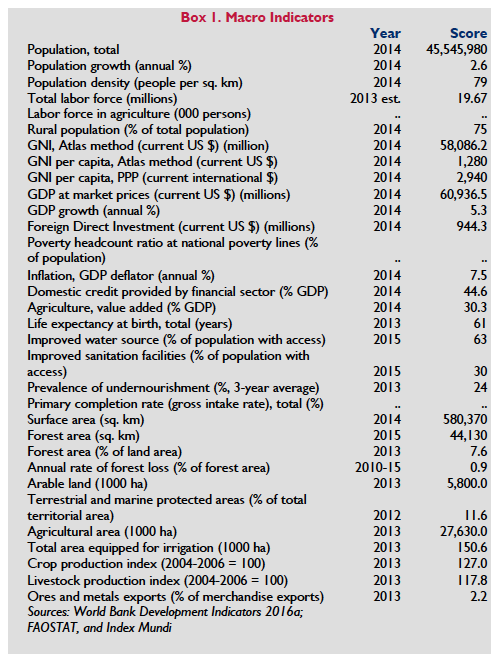

Kenya’s population of 45.5 m in 2014 is growing at 2.6 percent per year. Its economy grew by 5.3 percent in 2014 and is projected to grow between 5.4 percent and 5.7 percent in 2015 and 2016, supported by lower energy costs, a stable macroeconomic environment, strong infrastructure spending, an improved business environment, increasing exports and stronger regional integration. Economic growth was broad-based with all sectors (agriculture, manufacturing and service) contributing, with notable growth in infrastructure spending and strong consumer demand.

Kenya’s population of 45.5 m in 2014 is growing at 2.6 percent per year. Its economy grew by 5.3 percent in 2014 and is projected to grow between 5.4 percent and 5.7 percent in 2015 and 2016, supported by lower energy costs, a stable macroeconomic environment, strong infrastructure spending, an improved business environment, increasing exports and stronger regional integration. Economic growth was broad-based with all sectors (agriculture, manufacturing and service) contributing, with notable growth in infrastructure spending and strong consumer demand.

Kenya met some of its Millennium Development Goals (MDG) targets including reduced child mortality, near universal primary school enrollment and narrower gender gaps in education. Kenya has the potential to become one of Africa’s success stories due to its growing and youthful population, a dynamic private sector, and new constitutional and legislative reforms. Achieving this promise will require addressing challenges of poverty, inequality, governance, and low productivity (World Bank 2015a and 2015b).

Still, Kenya faces significant challenges. Nearly half its population lives below the poverty line or is unable to meet daily nutritional requirements. It ranks 145th among 187 countries in the UNDP’s Human Development index. Three-quarters of the population live in rural areas where agriculture is the mainstay of livelihoods, but that population is concentrated on medium- to high-quality land representing less than 20 percent of the country’s total land area. High population growth and land use pressure are increasing the vulnerability of young people and women to poverty. Only 46 percent of the rural population has access to clean water and the pace of deforestation, soil erosion and domestic and industrial population have intensified in recent decades. While the 2010 Constitution ensures the right to adequate food, 24 percent of the population is undernourished and cereal imports comprise one-third of the country’s needs. Climate change is a major challenge; drought and floods have increased in frequency and intensity over the past decade, dampening crop and livestock productivity (IFAD 2016).

Land

LAND USE

Kenya covers an area of 580,370 square kilometers. Of its total land area (56.9 million ha excluding inland water bodies) in 2013, 48.5 percent was agricultural land (arable land plus land under “permanent crops” and “permanent pastures”), 10.2 percent was arable, 0.9 percent was permanent cropland (mainly coffee, tea and horticulture), 37.4 percent was permanent meadows and pastures, and 7.6 percent was forested. Only 150,600 ha was equipped for irrigation in 2012 or 0.5 percent of agricultural area. Terrestrial protected areas encompassed 11.6 percent of Kenya’s land area in 2012 (Knoema 2016). An estimated 25 percent of Kenya’s 45.5 million people live in urban areas, highlighting the importance of land access for rural livelihoods.

Kenya’s economy is largely dependent on agriculture and tourism. Agriculture accounts for about 30.3 percent of GDP and 69 percent of the total economically active population gains its livelihood from agriculture. Of the total value of agricultural production of $11.5 billion in 2012, crop and livestock production comprised 64.1 percent and 35.9 percent respectively; of total crop value, cereal production comprised only 25.5 percent (Knoema 2016). Crop production as measured by the crop production index over the period 2004-06 to 2013 (Box 1) barely exceeded population growth while livestock production lagged, increasing dependency on food imports to meet food security needs.

The country is a world leader in the export of tea, coffee and horticultural products. The dairy sector is among the best developed in Africa and the Kenya Highlands are one of the continent’s most successful agricultural production regions. Agriculture accounted for 58 percent of Kenya’s exports of $5.22 billion in 2013; top exports include tea ($915 m), refined petroleum ($680 m), cut flowers ($642 m), coffee ($209 m) and legumes ($162 m). Kenya is the world’s leading exporter of black tea, providing income and employment to 600,000 smallholder households and 150,000 workers on tea estates (USDA 2013). Kenya is the largest supplier of cut flowers to the European Union; its shipments were estimated to reach 120,000 tons in 2014, accounting for approximately one-third of cut flowers sold in the European Union, and over 30 percent of the global cut-flower market (Bloomberg Business 2015). Coffee is primarily produced, processed, and marketed through cooperatives. Up to six million Kenyans are employed directly or indirectly in the coffee industry (Wikipedia 2016).

The livestock sector contributes an estimated 12 percent to total GDP and 47 percent to agricultural GDP. The livestock population is concentrated in the Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASALs) (75 percent of total surface area) where the livestock sector accounts for 90 percent of employment and more than 95 percent of family incomes. These areas have the highest incidence of poverty and very low access to basic social services (FAO 2005).

Pastoralists in Boran, Gabra and Garri in the border areas of northern Kenya and southern Ethiopia have long relied on moving herds between dry and wet season pastures based on primary and secondary rights of use negotiated with different pastoral groups in order to regulate sharing of water and pasture.

For decades, the viability of these systems has been weakened by state policies that have failed to recognize the legitimate right of pastoralists to rangeland resources. Thousands of pastoralists have been forced into urban centers and alternative livelihoods because of perceptions that pastoralism is linked to backwardness and poverty. Conflict has escalated, traditional rules and practices have eroded and pastoral livelihoods have been weakened as a result (Pavanello and Levine 2011). Kenya’s Community Land Bill offers a new approach to securing the rights of pastoralists to land, grazing and water through devolved governance and greater influence over decisions affecting their livelihood (Letai 2014).

Kenya’s estimates of livestock numbers and the contributions of livestock to the economy have increased in recent years. A study by IGAD and the Kenya Bureau of Statistics in 2011 showed that livestock’s contribution to Kenya’s GDP was more than two and half times larger than the 2008 official estimate.  Kenya’s livestock numbers were underestimated because the size of herds was not known, had not been enumerated for decades, and were based on official sales records which missed livestock that was informally traded or directly consumed. In 2009, a new livestock population census was undertaken and it estimated Kenya’s livestock numbers at 17.5 million cattle (versus 13.5 m officially in 2008), 17.1 million sheep (versus 9.9 m official), 27.7 m goats (versus 14.5 m official), 3.0 m camels (versus 1.1 m official), 1.8 m. donkeys (versus 0.8 m official), 335 k pigs (versus 330 k official), and 31.8 m chickens (versus 29.6 m official). Based on these new estimates, agriculture and forestry are Kenya’s most important sectors in terms of production, and livestock provides about 45 percent of output from these sectors combined (ICPALD 2013).

Kenya’s livestock numbers were underestimated because the size of herds was not known, had not been enumerated for decades, and were based on official sales records which missed livestock that was informally traded or directly consumed. In 2009, a new livestock population census was undertaken and it estimated Kenya’s livestock numbers at 17.5 million cattle (versus 13.5 m officially in 2008), 17.1 million sheep (versus 9.9 m official), 27.7 m goats (versus 14.5 m official), 3.0 m camels (versus 1.1 m official), 1.8 m. donkeys (versus 0.8 m official), 335 k pigs (versus 330 k official), and 31.8 m chickens (versus 29.6 m official). Based on these new estimates, agriculture and forestry are Kenya’s most important sectors in terms of production, and livestock provides about 45 percent of output from these sectors combined (ICPALD 2013).

Unfortunately, wildlife numbers have drastically declined. Using remote sensing data to analyze changing land use patterns between 1980 and 2013, Nyamasyo and Kihima (2014) documented a noticeable increase in size of farmland and settlement; a decline in forest land, grassland, wetland and woodland; and a decline in wildlife numbers due to habitat destruction, human-wildlife conflict, land degradation, and displacement of wildlife by livestock.

LAND DISTRIBUTION

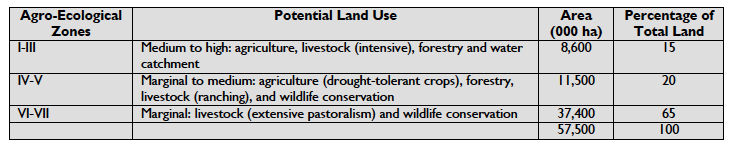

Approximately 17 percent of Kenya’s total land area is suitable for rainfed agriculture. Kenya’s agricultural potential spans seven agro-climatic zones determined by climate, hydrology and terrain (Kenya Land Alliance 2000; Orodho 2006):

Intensive cultivation is prevalent in the high-potential highlands where rainfall is above 1,200 mm annually and soils are rich. Common crops include tea, coffee, sugarcane, maize and wheat. Approximately 75 percent of the population lives in medium to high potential areas of zones I-III. Semi-arid land (zones IV-V) covers about 20 percent of the entire land area and is inhabited by 20 percent of the population. The ASAL area, which includes agro-ecological zones IV to VII, is approximately 49 million hectares (ha). It covers most parts of the northern, eastern, and southern margins of the central Kenya highlands. The arid area, which covers 60 percent of the total land is inhabited by 10 percent of the population. In the ASAL, incidences of crop failure are common; the predominant land use systems are ranching, wildlife conservation and pastoralism. Despite the appearance of land shortage, large areas of prime land are idle and owned by absentee land owners (Kenya Land Alliance 2000).

Land distribution is very much skewed because of well-documented illegal appropriations of public land by elites during the late 1980s and 1990s. In rural areas, three prominent extended families of past presidents hold significant amounts of land (McLaren 2009). Most of these large holdings are concentrated within the 17 percent of the country that is arable. More than half of the arable land in the country is in the hands of only 20 percent of the population. This has left 13 percent of the population absolutely landless while another 67 percent holds, on average, less than a half ha per person. However, determining land ownership concentration is difficult because the land is held in different names and widely distributed among numerous family members (Namwaya 2011).

In Nairobi, five percent of the land is providing housing for 75 percent of the city’s population. Over half of the total urban population lives in extremely dense informal settlements. The majority of slum-dwellers (92 percent) are rent-paying tenants with varying levels of tenure security. The buildings they occupy are owned by absentee landowners who provide extremely poor housing units without basic services (Oxfam Great Britain 2009; World Bank 2008; Economist 2007). The urban housing shortage is high and affordable rental housing is limited due to under-investment in low and middle-cost housing; an outdated legal framework; uncoordinated policy; and the high cost of finance. High rates of urbanization and escalation of housing costs and prices have made provision of housing, infrastructure and community facilities one of Kenya’s daunting challenges (McLaren 2009).

Tenure in informal settlements is varied. One study compared tenure systems between three informal settlements of Nairobi – Kibera, Mukuru Kwa Njenga, and Mathare. Kibera, an Islamic (communal) tenure system, allows ownership of structures and use for residence and building purposes but prohibits sale of community land or leasing outside the community. Mukuru Kwa Njenga consists of two tenure types. In the first, land is administered by an administrative chief who, along with a headman, allocates plots, collects rents, and decides on transfers; plot owners may rent out structures and bequeath property to heirs. In the second type, land is managed by five self-help groups with elected officials who are the land administrators. Shareholders can sell their shares to third parties with approval of the group. In Mathare, one landlord holds a lease from the government; tenants have written contracts and legal security of tenure. However, their rights are limited to occupation and inheritance; leasing is restricted to original residents and their decedents. In all three, land markets are restricted and security of tenure derives from group membership (Siakilo 2014).

Land inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient was 0.612 based on reported size of ownership in 1997. Nationally, there was a 36 percent increase in the Gini over the period 1997–2005/6 to about 0.83 for landholdings in the entire population. The increase in the Gini is linked to worsening inequality, which was marked in the Coast and Nyanza provinces and in rapidly-growing urban areas (World Bank 2008; Oxfam Great Britain 2009).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The NLP, adopted in December 2009, called for the replacement of a patchwork of often incompatible laws from the colonial period. The policy: 1) recognizes and protects customary rights to land; 2) outlines principles of sustainable land use and provides productivity and conservation targets and guidelines; 3) calls for reform of land management institutions to ensure devolution of power, increased participation and representation, justice, equity, and sustainability; 4) calls for the establishment of the National Land Commission (NLC), District Land Boards, and Community Land Boards; 5) calls for the development of a legal and institutional framework to handle land restitution and resettlement for those who have been dispossessed; and 6) calls for reconsideration of constitutional protection for the property rights of those who obtained their land irregularly. While transformative in intent, the policy objectives enshrined in the NLP will only be fulfilled through enactment and enforcement of new laws and regulations which continues to be a work in process. The NLP also focuses heavily on agrarian land issues and places less emphasis on urban areas (GOK 2009b; USAID/Kenya 2009a; Hilhorst and Porchet 2012).

Chapter 10, Art. 62, of the Constitution states that “all land in Kenya belongs to the people of Kenya, collectively as a nation, as communities and as individuals.” Land is classified as public land, private land and community land. Since passage of the NLP in 2009, Kenya has undertaken an extensive overhaul of legislation governing these different land categories (Table 1).

Following promulgation of the 2010 Constitution, the National Constitution Implementation Commission, in consultation with the Ministry of Lands, identified seven bills for proposed enactment—the Land Bill, the Registration Bill, the Environment and Land Court Bill, the Kenya National Land Commission Bill, the Matrimonial Property Bill, the Private Land Bill and the Community Land Bill. Six of these bills have been legislated as Acts of Parliament while the other is in the process of consultation. This new legal framework repeals a collection of colonial and post-colonial statutes that include, among others, The Indian Transfer of Property Act 1882; The Government Lands Act; The Registration of Titles Act; The Land Titles Act; The Registered Land Act; The Wayleaves Act; and The Land Acquisition Act (Chapman et al. 2014). The 1967 Land Control Act governing subdivision, sale, transfer, lease, mortgage or other transfer of interests or rights was not repealed but is implemented by the Land Control Regulations 2012.

Between independence and 1990, land tenure reform was effectively thwarted by the executive. However, the 1990s and beyond began a new era of land tenure reform. The Njonjo Land Commission was appointed in 1999 to review the land law systems of Kenya and develop principles for a National Land Policy. The Ndung’u Land Commission of 2003 was an inquiry into the illegal/irregular allocation of public land and revealed a serious crisis in land grabbing by well-connected individuals. Both the NLP and Constitution implemented the findings of the Njonjo and Ndung’u Commissions. In 2011, the Environment and Land Court Act was enacted to establish the Court. On April 25 and 26, 2012, Parliament passed three bills—The 2012 Land Act, The 2012 Land Registration Act, and The 2012 National Land Commission Act that, along with anticipated legislation, promise to fundamentally transform land tenure relations in Kenya (Wakoko, n.d.):

- The 2012 Land Act. Governs the management and administration of public, private and community land according to principles of: 1) equitable access to land and security of land rights; 2) sustainable and productive management of land resources; 3) transparent and cost effective land administration; 4) elimination of gender discrimination in land and property law, customs, and practice; 5) encouragement to settle land disputes through recognized local community initiatives; 6) promotion of accountable, democratic and participatory decision making; 7) affording equal opportunities to members of all ethnic groups; and 8) non-discrimination and protection of the marginalized. The Act further provides for land allocation and land settlement; creation of a Land Settlement Fund; and an assessment of the economic viability of minimum and maximum acreages regarding private land for various land zones in the country.

- The 2012 Registration Act. Applies to registration of interests in all public, private, and community land. The Act defines powers of the Chief Land Registrar and other Land Registrars and provides for survey and mapping, certificates of title, and protection of persons receiving land. It further makes special provisions for the registration of leases and charges, places certain restrictions on dispositions regarding interests in land, and provides for registration of rights regarding co-tenancy, partition, and easements.

- The 2012 National Land Commission Act. Provides for the administration, structure, operations, powers, and responsibilities of the NLC. The Commission is empowered to manage public lands on behalf of national and county governments, recommend national land policy to national government, encourage the application of traditional dispute resolution mechanisms, advise the national government on land registration, and recommend legislation for investigating and adjudicating claims arising from historical land injustices.

- The 2016 Community Land Act. Deals with the recognition, protection and registration of community lands, development of community land registers, outlines the nature of community land titles and rights associated with these, discusses the conversion of land and the special rights and entitlements associated with community land. The Bill also addresses the management of natural resources on community lands and dispute resolutions processes associated with grievances on community lands.

- The 2016 Land Laws (Amendment) Act. Aimed at resolving routine conflicts between the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Physical Planning and the NLC. It also contains provisions for receiving, investigating, and recommending solutions to claims on historical injustices, managing evictions, and curbing limits on minimum and maximum land holdings. Implementing regulations for these laws still need to be enacted. Parliament is currently seeking stakeholder input on the following (LDGI 2015):

- Physical Planning Bill 2015. Supports planning, use, and regulation to guide development of urban and rural spaces.

Until the late 1990s, the statutory framework for administering land in pastoral areas was driven by a modernization ethic. The Land (Representatives) Act (Cap 287) of 1968 advocated for promoting development of rangelands via group ranches to: improve productivity through increased off-take; increase earning capacity of pastoralists; avoid landlessness by allocating land to individual ranchers; control environmental degradation; and enable modernization of livestock husbandry. Government envisioned parceling trust land (for a definition see Table 2 below) into ranches with freehold titles held by groups of pastoralists sharing ranch infrastructure. Despite these intentions, group ranches did not successfully commercialize beef production, and problems with shared ownership led to widespread subdivision into individual plots. Few succeeded in the form intended (Veit 2011a; Letai 2014).

A number of group ranches have evolved into new governance structures for land use management, notably trusts and conservancies. For example, The National Rangeland Trust (NRT) was established in 2004 to develop resilient community conservancies, secure peace and conserve natural resources. It does so by raising funds for the conservancies, providing them advice, supporting them with training, and brokering agreements between conservancies and investors. NRT’s highest governing body is the Council of Elders comprised of chairs of the conservancies joined by members representing county councils, local wildlife forums, the Kenya Wildlife Service and the private sector. Community conservancies are legally recognized institutions, registered as not-for-profit companies, and run by democratically elected boards. The NRT is comprised of 33 conservancies, covering 44,000 km2, and 400,000 people. Examples include Lekurruki Conservation Trust located on 11,950 ha on Lekurruki Group Ranch in Laikipia North District; Namunyak Wildlife Conservation Trust located on 394,000 ha comprising six group ranches in Samburu East District; and Kalama Community Conservancy located on 46,100 ha at Gir Gir Group Ranch in Samburu East District (Northern Rangeland Trust, N.D.). With assistance of the NRT, the communities are engaged in programs aimed at improving governance, livelihoods, community enterprise development (including ecotourism), peace and security, wildlife management, and rangeland development.

Another example is II Ngwesi Group Ranch located in Laikipia District which was awarded the UNDP’s Equator Prize in 2002.2 The Ranch, 8,645 ha in size, is owned by many Maasai villages who have scaled back their livestock, are actively protecting wildlife and have opened a small lodge. All profits brought in by tourists are divided among the local community and help support nearly five hundred households and their schools, cattle dips, water supplies and other group ranch operations. One of the pioneering and most successful of Kenya’s Maasai-owned ecotourism initiatives, II Ngwesi has served as a model for replication across the country. In addition to freshwater management and education, ecotourism revenues have been invested in targeted health interventions. The group is a lead partner in a health campaign (offering awareness-raising, testing and counseling for HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis) targeting thirteen local group ranches for a combined population of 40,000 people (UNDP 2012).

Since the late 1990s, Kenya has begun to recognize the benefits of pastoralism and community rights over land and resources. Both the Constitution and the NLP lay down clear and concrete guidelines for securing community land. The emphasis should now be on implementing regulations and enforcement. There also remain gaps and uncertainties. It is yet to be seen how this new body of legislation will handle the urban land tenure issues identified in the previous section. The passage, in 2016, of the Community Land Act should help reduce risks for marginalized populations in coastal and pastoral areas by creating a process to recognize and protect their lands. For example, the new Act takes into consideration the customs and practices of pastoral communities so long as these are consistent with other applicable law.

TENURE TYPES

The NLP designates all land in Kenya as public, private (freehold or leasehold tenure), or community/trust land, which is held and managed by a specific community.

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

The most common method of obtaining land rights in Kenya is through inheritance, followed by purchase. Land leasing is common in some rural areas. The vast majority of leases are fixed rent; sharecropping is rare (Yamano et al. 2009). Any person (citizen or foreigner) can apply for and be allocated land in urban areas. Foreign individuals and companies may acquire land under a renewable leasehold from the government or landowners for investment purposes (GOK 2009b). Membership in a community through kinship ties and common descent is the primary basis for acquiring customary rights to land. Loss of membership means loss of access, which is particularly difficult for women whose membership depends on their relationship to male members (Odhiambo 2006). Throughout Kenya, security of tenure under both customary and statutory systems has been undermined by arbitrary decision-making, corruption, land takings, and lack of redress for those who have lost land through violence or public takings. County councils charged with protection of customary rights in rural areas have in many cases abused the trust bestowed on them and presided over the expropriation of these lands without regard to their constitutional mandate (Odhiambo 2006; Wakhungu et al. 2008).

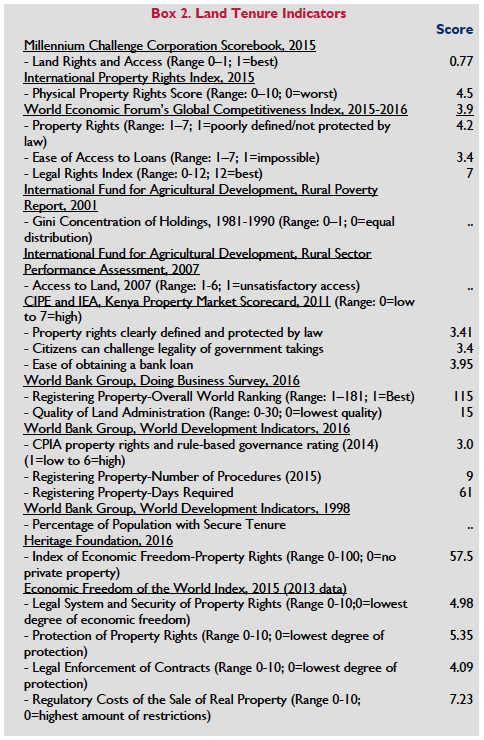

Kenya’s economy is gradually transitioning toward greater security of land and resource rights as evidenced by the major legal reforms undertaken since 2010 (see previous section), although enforcement and real state protection remains a challenge. It’s Economic Freedom score of 57.5 is on par with the region and is slightly above the world average. Economic development nevertheless remains constrained by weak rule of law, corruption, and a judicial system that is vulnerable to political influence (The Heritage Foundation 2016).

There is also a lack of awareness of the rules related to property rights and legal processes that inhibits property rights protection. The legal framework is too complex and difficult for most Kenyans to understand. Formal ownership is constrained by land speculation, corruption, political interference and abuse of power. Levels of ownership of urban property is low due to high real estate costs, leaving most people dependent on informal renting. Even where formal lease contracts exist, legal jargon may make it difficult for many people to understand lease terms and to negotiate for better terms. This contributes to exploitation by property owners. Illegal evictions and neglect of property service by landlords results in abuse of tenant rights. Most tenants lack basic services due to the high costs involved. While the NLP is aimed at rationalizing all the various laws under one policy, its implementation is yet to be fully realized. Simplification of laws and greater efforts to help the public understand them would go a long way to improving tenure insecurity (CIPE and IAE 2011).

The land registry system also makes it difficult to access land cadaster information. The system is still manual and highly centralized despite efforts at decentralization. Multiple registrations of single plots of land are common while the slow pace of formal land transactions encourages extra-legal payments (CIPE and IAE 2011). However, the land registry of Nairobi has recently gone through a full digitization of its records and is now developing new electronic services for its customers. The speed of property transfers is increasing because of improved electronic documents management and the introduction of a unified form for registration (World Bank 2016b).

The indicators in Box 2 thus tell a fairly consistent story—Kenya is gradually emerging from a period in the 1990s to the late 2000s marked by tenure insecurity, political instability and violence, and heading towards a new era of property rights freedom and legal reform. But as most indicators suggest, Kenya still has a long way to go before tenure security for the majority of Kenya’s urban and rural population is achieved. The difficult task of devolving power, formalizing rights and providing protection remain, posing ongoing challenges for years to come.

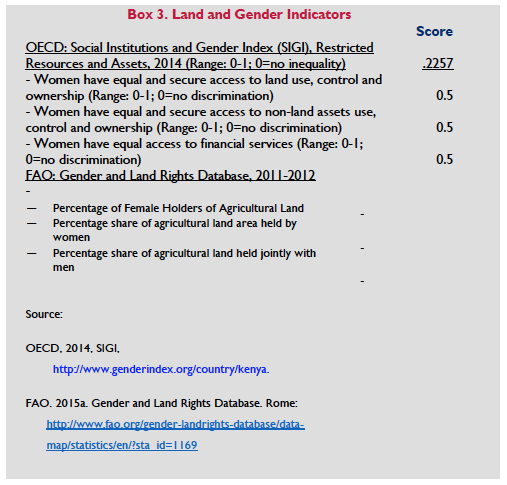

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Despite the fact that 89 percent of Kenya’s subsistence labor is provided by women, and 32 percent of households are headed by women, only 1 percent of land titles are held by women alone and another 5 percent are held by women jointly with men. Women are hindered from enjoying full land and property rights by cultural beliefs, lack of awareness, discrimination, an expensive legal system, fear of reprisal or being ostracized, lack of official representation in decision making bodies, and family laws that are gender insensitive or have entrenched discrimination (FIDA-Kenya 2013).

Despite the fact that 89 percent of Kenya’s subsistence labor is provided by women, and 32 percent of households are headed by women, only 1 percent of land titles are held by women alone and another 5 percent are held by women jointly with men. Women are hindered from enjoying full land and property rights by cultural beliefs, lack of awareness, discrimination, an expensive legal system, fear of reprisal or being ostracized, lack of official representation in decision making bodies, and family laws that are gender insensitive or have entrenched discrimination (FIDA-Kenya 2013).

Kenya is a patriarchal society; women are marginalized in most aspects of their lives. Women are particularly vulnerable in cases of divorce given a legal system that makes it difficult for them to obtain their rightful share of property. Widows and their children are often evicted from their homes. Lack of alternative housing and livelihood options often means that widows and their children migrate to urban slums where they eke out a sub-standard living (FIDA-Kenya; IWHRC 2008). Fear of dispossession renders them vulnerable to domestic violence or abusive relationships. Women are further excluded from decision making processes as men hold the vast majority of seats in institutions that adjudicate land rights. As a result, women must often rely on men for their welfare (FIDA-Kenya; IWHRC 2008).

Kenya’s 2010 Constitution provides a Bill of Rights that: recognizes the right of women to equal treatment under the law; prohibits gender-based discrimination; and requires that women make up at least one-third of the members of elected or appointed political bodies. The National Land Commission Act of 2012 prohibits gender discrimination in law, custom and practice. The Land Act of 2012 prohibits culturally biased practices that hinder women’s participation in the control of land. The Land Registration Act of 2012 creates a presumption that spouses shall hold land as joint tenants, that women will participate in settlement processes, and that a sale or charge is void without consent of the spouse (FIDA-Kenya 2013).

Beyond these Acts, a new set of marriage laws—Matrimonial Property Act of 2013 and Marriage Act of 2014—have been enacted. The Matrimonial Property Act provides some clarity on spousal rights, in particular by defining women’s contribution for domestic work and child care, but it remains to be seen how the courts will apply the Act (Gaafar 2014). Despite the Law of Succession’s Act intestate provisions treating daughters and sons equally, women rarely inherit land. Further, the Succession Act and Matrimonial Act allow for exclusion of inherited property or ancestral land from matrimonial property (Gaafar 2014). Women in Kenya are granted a “life interest” in property rather than full ownership, which prevents them from using it as collateral for bank loans or disposing it as they see fit. In the event of her husband’s death, this “interest” disappears upon her remarriage. Even when women acquire assets in their own name, their husbands often act as intermediaries (OECD 2014).

Customary tenure and community rights to land are legally recognized in the Constitution and under the Community Land Act “women, men, youth, minority, persons with disabilities and marginalized groups have the right to equal treatment in all dealings in community land (Article 30(1)). The Community Land Act goes on to prohibit direct and indirect discrimination based on race, gender, marital status, ethnic or social origin, color, age, disability, religion or culture.

Although the Land Act creates an Environment and Land Court for determining and protecting land rights, only time will tell whether it will be successful in curbing discriminatory practices against women (OECD 2014). However, the principles established in the Constitution and the recent enactment of progressive property, marriage and succession legislation gives teeth to challenges of gender discrimination. These new laws have the potential to affect long term positive change. But, until they are proven to be effective, women’s customary rights to property in Kenya remains severely limited.

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Land administration since independence in 1963 was implemented under the Ministry responsible for land (now the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development) through four departments: Lands, Surveys, Land Adjudication and Physical Planning. The NLP called for a new devolved structure of land administration comprising democratically elected Community Land Management Boards (CLMBs) responsible for managing community lands and approving all transactions, and District Land Boards (DLBs) assuming district-level responsibilities of the Ministry of Land (GOK 2009b, Siriba and Mwenda 2013). The 2010 Constitution also provides for a decentralized two-tier government consisting of National and County governments (Siriba and Mwenda 2013). The 2012 legislation, in particular the National Land Commission Act, envisioned a NLC establishing county offices, and county governments carrying out the functions of physical planning, land surveying, mapping, land adjudication, consolidation, and settlement (Siriba and Mwenda 2013).

The NLP further recommends the strengthening of surveying and mapping systems; computerized land information at national and local levels; a National Spatial Data Infrastructure to integrate and standardize spatial datasets maintained by different agencies; and the documentation and mapping of communally owned land (the largest percentage in rural areas) which has not been registered or mapped (Siriba et al. 2011).

The constitutional requirement to decentralize powers to the county level creates significant challenges. A 2016 survey looked into the status of public land management by public institutions holding large tracts of land and CLMBs. Only 77 percent of the institutions interviewed were aware of the extent of their land holdings; of these only 41 percent had documentation verifying ownership. Of CLMBs surveyed, most lacked geo-referenced maps and corresponding registration status verifying their land inventory. Despite provisions in the Constitution and Land Act, there has been a resurgence of attempts to irregularly or illegally acquire land; CLMBs repossessing land is one of several strategies being adopted to address this issue (LDGI 2016a). Beyond staff recruitment, rationalization, reorganization of land registries, and computerization of records, other interventions could improve service delivery and reduce rent seeking. These include the following: fully staffed customer care desks, holding officers accountable for timely and regular reporting, sporadic inspection visits by senior officials, adherence to service charter timelines, equipment (computers, typewriters and photocopiers), and basic induction and change management courses to cultivate a customer service attitude (LDGI 2016b).

While existing land laws may be suitable for sedentary use if well enforced, they certainly do not address the needs of pastoralists for extensive dry season mobility, or deal with livestock corridors that overlap private land. However, it’s possible to predict where pastoralists will be at any given time or during drought periods and so it is possible to map and record their traditional spatial and temporal land rights in registries and on land administration maps (Lengoiboni et al. 2010).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

In Kenya, 85 percent of the population depends on agriculture yet 88 percent hold less than 3 ha of land. Friction ensues between state, communities, and investors because of two interlinked factors: the disappearance of large tracts of public land and the enormous wealth accumulated by Kenya’s wealthy elites. Public land and “trust” (community) land bore the brunt of irregular and illegal land acquisition facilitated by government abuse of power, a highly centralized land administration system, and political patronage (O’Brien 2011; Makutsa 2010).

Under the Land Control Act, local Land Control Boards (LCBs) must approve all transactions in agricultural land, including sale, lease, mortgage, and subdivision. They have wide discretion over whether or not to approve a transaction, with an option to appeal to the Provincial and then to the Central Land Control Body (Ellis 2007). Land transactions are often a cumbersome process. In some cases, a single parcel is allocated to multiple people, proper records not kept, people may have to rely on real estate agents for information, buyers may pay for land that doesn’t exist, and the time/cost associated with formalizing rights is substantial (Kariuki and Nzioki 2011). Registering land transfers requires nine procedures and takes approximately 61 days (Box 2). As a result, many land sales and transfers are not reported to the Land Control Boards (World Bank 2009b). NLP proposals to decentralize land registries, expand registration, and devolve authority would facilitate a more efficient land market, but as shown earlier, would also entail significant challenges.

The Land Control Act prohibits the transfer of land to foreigners, but it conflicts with the Investment Promotion Act that empowers the Kenya Investment Authority to provide an investment certificate to foreign interests if a land-based investment creates employment for Kenyans; offers new skills or technology for Kenyans; contributes tax revenues; increases foreign exchange; or utilizes domestic raw materials and services (Makutsa 2010). Investors are usually given long-term leases up to 99 years. Under the new Land Commission Act, the NLC is charged with administering public land to control against fraudulent acquisitions. Nevertheless, the present land governance system is inadequate to cope with increasing pressure on land resources (Nolte and Väth 2013).

The Yala wetlands and Tana River Delta are focal areas for large scale investment. The Tana River Delta covers an area of about 130,000 ha in a triangle extending from Garsen in the north, Kipini in the east to the Milindi road in the south and west. Large scale investments targeting the Delta and surrounding area exceed 500,000 ha (Makutsa 2010). Investments include G4 Industries proposing to grow crambe, castor and sunflower on 28,911 ha; the Emirate of Qatar is engaged in horticulture production on 40,000 ha, and Mat International Limited is interested in acquiring 30,000 ha (plus 90,000 ha in adjacent districts) for sugar cane production. There are also local lease arrangements—Mumias Sugar Company was granted a license to convert wetlands into sugar cane production;4 40,000 ha was allocated to Tana & Athi Rivers Development Authority to grow rice and maize; and Jatropha Kenya Ltd, a subsidiary of an Italian company, leased 50,000 ha to grow jatropha for biofuel extraction (Otieno 2014). The Yala wetlands, located on the north-eastern shore of Lake Victoria, is under the custody of the Siaya and Bondo County councils. In 2003, Dominion Farms Ltd acquired 6,900 ha of 17,500 ha of wetlands under the Yala Swamp Integrated Development Project for a period of 25 years (FIAN International 2010).

These and other investments have met with protests over loss of ancestral land rights, disruption of livelihoods, poor working conditions and inadequate compensation. In Tana Delta Region, between August 2012 and February 2013, widespread violence that erupted between two warring communities and multinational investors claimed the lives of over 200 people and displaced more than 1000 people.

Foreign land leases promise enhanced production, employment, technology, capital, and infrastructure. However, these benefits are only possible if the deals structured are participatory and transparent. The NLP, while addressing leases and land investment, has otherwise ignored requirements related to local stakeholder participation in the management of foreign-held land leases (Otieno 2014). When interviewed about their perceptions to land deals, 60 percent of people in one study felt that well-managed leases could offer economic benefits, but also feared displacement. Those interviewed expressed preferences for leases: where communities would negotiate size and price; that provide formal contract employment rather than casual work; and, that last for 15 years or less to avoid conflicts between developers and descendants. Future land leases could be improved by considering local opinions on lease durations, sizes, renewability and the provision of compensation (Otieno 2014).

In Kenya, medium-scale farms control 0.84 million ha while large scale-farms control 0.69 million ha. The remaining 2.63 million ha is controlled by smallholder farms. There is a strong inverse correlation between landholding size and proportion of land under cultivation. The rise of medium-scale farms reflects a rising demand for prime land by more affluent people. Income growth in urban areas is contributing to land scarcity and higher land prices (KLA and MSU 2014). One study shows that farm productivity and incomes rise with population density up to 600-650 persons per km2, but beyond this threshold, rising population is associated with sharp declines in farm productivity, income and asset wealth. About 14 percent of Kenya’s rural population exceeds this threshold, thus underscoring the urgency to correct land inequality that contributes to rural poverty (Jayne and Muyanga 2012).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The Government’s power to compulsorily acquire land for public purposes is authorized by Article 40(3)(b) of the 2010 Constitution, while the procedures are provided in the Land Acquisition Act of 1968. Property can be acquired subject to prompt payment of compensation, and citizens have rights of redress through the courts. Government has considerable authority to restrict rights via zoning regulations, land use plans, sub-division policy and other land use restrictions (Veit 2011b). Precipitated by land grabs by wealthy and political elites prior to 2010, the National Land Commission Act 2012 empowered the Commission to manage the acquisition of all public land and all unregistered community land on behalf of county governments (Doshi et al. 2014).

The Compulsory Acquisition Procedure is as follows: (1) the Minister of Lands directs the Commissioner of Lands to identify land to be acquired (no public participation); (2) the Commissioner publishes a notice of intention in the Kenya Gazette; (3) the Commissioner publishes a notice of inquiry to hear claims for compensation; (4) the Commissioner convenes a public inquiry on compensation (land, houses, trees, crops, structures and fixed improvements are eligible, and property owners are compensated with land or paid at market price); (5) the Commissioner awards compensation; and (6) the Government takes possession of the land. Aggrieved persons can petition the court prior to the award of compensation (Veit 2009).

Despite well-established procedures, the GOK has carried out large-scale forced evictions of informal urban settlements for decades. Forced evictions also occur in forest areas, purportedly in the interest of forest conservation and preservation (AI n.d.; AI 2007; Mutai 2010). And, land takings by political elites and for agricultural investment have disenfranchised the land, assets and livelihoods of indigenous populations.

While legal reforms since 2010 have muted these powers or subjected them to greater scrutiny, compulsory land acquisition is still contributing to land related conflict. Developers are concerned over the exercise of private land restrictions on economic growth and development while those impacted by land takings are concerned about compensation for property lost and due recourse. There is need to strike a balance between these competing interests in Kenya’s politically charged land debate; mechanisms for doing so include establishment of a high jurisdictional standard, development of strong and clear public purpose requirements, rigorous cost-benefit analysis to justify takings, and democratizing expropriation procedures (Veit 2011b).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Land disputes were a source of conflict in the aftermath of the post-election violence experienced in Kenya in early 2008. The Kenya National Dialogue and Reconciliation process identified land reform as key to long-term peace and reconciliation, and the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission was mandated to examine historical land injustices and the illegal or irregular acquisition of land, especially as these relate to conflict or violence (Yamano and Deininger 2005; Huggins 2008).

Tensions also exist between pastoralists living on land that traverses or abuts parks, ranches and protected areas, and the owners and administrators of these areas. Up to 90 percent of wildlife is located outside protected areas increasing the risk of human-wildlife conflict (Nyamwaro 2006). The challenge to conservation is how to enhance co-existence between people and wild animals, particularly as people infringe on wildlife habitat. The main wildlife problems include: crop damage, competition for water and grazing, livestock predation, disease and human fatalities. There are two basic approaches to managing human-wildlife conflict: 1) prevention including forced removal of people or wildlife, use of barriers, employing scaring tactics, and killing or translocating problem animals; and 2) changing the attitudes of affected communities to wildlife and conservation institutions by ensuring that people are active participants in, and enjoy tangible benefits from, wildlife management (Makindi et al. 2014).

The Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) implements a scheme to share revenue generated from park entrance fees to encourage community participation in wildlife conservation but there have been concerns about lack of transparency and equitable distribution of funds. It also provides compensation to landowners who support wildlife on their land and for property destroyed but the compensation is usually insufficient or not proportional to the loss (Nyamwaro 2006; Makindi et al. 2014). In one study of Tsavo Conservation Area, respondents recommended the following remedies: a) enclose animals in the conservation area via an electric fence; b) have KWS compensate for damaged property and human injury but with caveats (done quickly, procedures shortened, and pay compensation for crops and trees); c) encourage KWS to be more vigilant in managing wildlife; d) increase payments for wildlife protection; and f) educate communities and create conservation awareness (Makindi et al. 2014). Although important, these recommendations depend on scarce public funds and government oversight in managing conflict, and ignore the potential role of trusts, conservancies and other forms of land use interventions in leveraging private sector funding, strengthening public-private partnership and increasing incentives for wildlife protection.

Climate change and growing land scarcity are contributing to increasing conflict over land and water resources. In 2012, clashes broke out between the Pokomo (predominantly sedentary farmers and fishermen) and Orma (nomadic pastoralists) communities in southeast Tana River County with death tolls estimated at over 100. As a result of loss of livelihoods, the Pokomo spread into areas they did not originally occupy, while the Orma face dwindling supplies of pasture and water so have moved closer to the banks of the Tana. Compounding this tension, the National Environment Management Authority in 2011 licensed three major projects converting 100,000 ha of wetlands to large-scale bio-fuel production leading to displacement of both communities (Asaka 2012). Women pastoralists and agro pastoralist societies are negatively impacted in two ways: while typically not land owners, as the owners of the home and garden plots they risk loss of property; and suffer from assault and beatings that result from raids, eviction and displacement (Young and Sing’Oei 2011).

Climate change and growing land scarcity are contributing to increasing conflict over land and water resources. In 2012, clashes broke out between the Pokomo (predominantly sedentary farmers and fishermen) and Orma (nomadic pastoralists) communities in southeast Tana River County with death tolls estimated at over 100. As a result of loss of livelihoods, the Pokomo spread into areas they did not originally occupy, while the Orma face dwindling supplies of pasture and water so have moved closer to the banks of the Tana. Compounding this tension, the National Environment Management Authority in 2011 licensed three major projects converting 100,000 ha of wetlands to large-scale bio-fuel production leading to displacement of both communities (Asaka 2012). Women pastoralists and agro pastoralist societies are negatively impacted in two ways: while typically not land owners, as the owners of the home and garden plots they risk loss of property; and suffer from assault and beatings that result from raids, eviction and displacement (Young and Sing’Oei 2011).

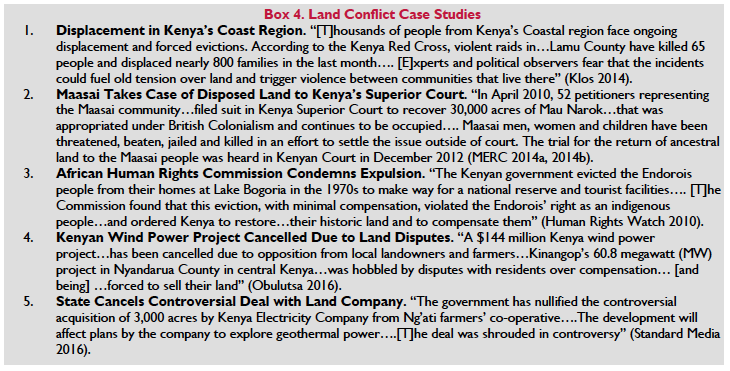

New provisions anchored in the NLP are intended to help reduce land related conflict: the NLC is supposed to manage all public land; there is a prohibition on freehold titles to foreigners, conversion of freehold titles and 999-year leases to 99-year leases; an investigation of historical injustices and establishment of mechanisms for resolving post-1895 land claims should be established; and repossession of public land grabbed or acquired illegally should move forward (Kamakia 2015). Still as indicated in Box 4, the scale of historical redress is massive, and creates a huge challenge in balancing community interests and rights with the needs of private and public investment.

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The new Constitution and NLP ushered in a new governance system that aims to strengthen accountability and public service delivery at local levels. County governments are implementing constitutional and legal provisions for transparency and accountability, and setting up structures (websites, communication frameworks and forums) to facilitate public participation.

Both the NLP and Constitution implemented the Ndung’u Commission findings on the illegal/irregular allocation of public land and addressed the issues of land grabbing by wealthy and political elites. In 2011, the Environment and Land Court Act was enacted to establish the Court. In 2012, Parliament passed the 2012 Land Act, the 2012 Land Registration Act, and the 2012 National Land Commission Act which fundamentally transform land tenure relations in Kenya. The NLC has been established and begun work on developing a land management and administration system that is equitable, efficient, and cost-effective. This work has been followed up with the passage of the Community Land Act and the Land Laws (Amendment) Act.

The Government has also been busy decentralizing and improving the effectiveness of its land administration and justice systems with support of donors. However, while transformative in substance and scope, the reforms are nonetheless relatively new and in the early stages of implementation. Ongoing reform efforts should be expected as land tenure reforms, decentralization and devolution is implemented, tested, and learned from.

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

Civil society has been very engaged in land related research and advocacy. The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) works with a number of advocacy groups including the Federation of Female Lawyers and the Kenya League of Women Voters in combatting discrimination in political decision-making and inheritance of land and property. The UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), once the major supporter of land policy and reform in Kenya, discontinued its support for land reform in its 2011-2015 plan “due to difficulties in achieving results” (DFID 2012).

Since 2008, USAID has emerged as the main donor working with government and civil society in advancing the principles of the 2009 NLP and 2010 Constitution. USAID conducted a review of the draft NLP in 2008, followed by ongoing support with land reform implementation through multiple projects:

- Supporting GOK Reform Efforts through the Kenya Transition Initiative, 2008-2013. assisted a wide range of government and civil society actors with grants. It provided support for organization of files and records, land transaction processing, and Constitutional and land law training in the Nakuru, Trans Nzoia and Kilifi District Offices; helped in modernizing the Kajiado and Thika Lands Registries to improve data and land records storage and management; assisted multiple actors with land research, legal advocacy and public information and awareness raising; and worked with Parliament to create a more transparent process for drafting land reform legislation and helped establish the NLC (USAID 2014a, 2014b).

- Securing Rights to Land and Natural Resources and Livelihoods in the Kiguna, Boni and Dodori Reserves and Surrounding Areas (SECURE) project, 2009-2013. The region is home to three national reserves that incorporate 2,500 km2 of coastal ecosystems managed by local communities. But land speculation and illegal land transactions are rampant. The project worked closely with the Land Reform Transformation Unit of the Ministry of Lands to design a participatory Community Land Rights Recognition (CLLR) Model that lays out steps to register community land and to protect customary institutions against arbitrary abuses of power by local elites and administrators (USAID 2011).

- Enhancing Customary Justice Systems in the Mau Forest (Justice) project, 2010-2013. Piloted an approach for improving women’s access to customary justice in Ol Posimoru. The project delivered a training curriculum to targeted groups on civic education, legal literacy, rights and responsibilities related to land and forest resources; facilitated community conversations with target groups; and engaged in public information and education activities to reach the broader community. A follow on project in 2013 was intended to share approach, results and lessons learned and explore opportunities for broader application throughout Kenya (USAID 2013; Landesa 2013)

- SERVIR: Implementation of the Land Administration Domain Model for Kenya, 2014-2015. Support is provided to Dedan Kimathi University of Technology to develop a prototype of a web-based, GIS-driven land administration system that allows citizens, professionals and government to obtain land related information. Such system once developed by 2015 will be used to promote land use systems and policies that improve resilience to climate change (USAID 2015a). A 2016 paper discusses the process of developing the model (Kuria et al. 2016).

- Feed the Futures’ Resilience and Economic Growth in the Arid Lands – Accelerated Growth (REGAL-AG) project, 2013-2017, and Resilience and Economic Growth in the Arid Lands-Improved Resilience (REGAL IR) project, 2012-2017. Facilitate behavior change and improve the enabling environment by working with pastoral communities to advocate for improved national policies that will expand access to critical services and markets. Through 2014, the program trained more than 1,300 pastoralists on land use and tenure systems to improve environmental management (USAID 2014c).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Most of Kenya’s water originates from five water towers: Mau Forest Complex, Aberdare range, Mount Kenya, Mount Elgon and the Cherengani Hills. There are six main catchments in the country used as the unit for water resources management by the Water Resources Management Authority (WRMA). Average rainfall is 630 millimeters, but varies significantly both temporally and spatially. Inland water bodies, mainly 9 large lakes, cover 11,230 km2 (FAO 2015a). Successfully storing and distributing water resources has been a challenge, increasing vulnerability to climate change (UNEP 2010). Overall, availability of water is in short supply and growing scarcer with growth in population and industry.

Total estimated renewable freshwater resources are 20.2 billion m3/year, and renewable ground water resources are 3.5 billion m3/year, but there is a 3.0 billion m3/year overlap between surface water and groundwater, which results in total internal renewable resources of 20.7 m3/year. Adding inflows of water from Ethiopia’s Lake Omo (10.0 billion m3/year) increases total renewable water resources to 30.7 billion m3/year, or 692 m3/year per-capita in 2014. Per capita water consumption is projected to fall below the absolute water scarcity threshold of 500 m3/year by 2030 due to population increase, underscoring Kenya’s strong need to carefully manage water for basic needs. In 2013, water permits distributed by the WRMA allocated a total volume of 5.1 billion m3/year, of which 64 percent is directed towards agriculture use, 22 percent towards municipalities, and 14 percent towards industry (FAO 2015a).

Kenya’s irrigation potential is between 353,060 ha and 1,341,900 ha depending on the source. In 2010, approximately 144,100 ha were equipped for full irrigation (70 percent surface, 22 percent sprinkler, and 8 percent localized), and 6,470 ha for spate irrigation, totaling 150,600 ha.5 There are two major types of formal schemes: 1) private irrigation schemes comprised of community based schemes managed by water users’ associations, cooperatives and self-help groups (43 percent of total irrigated area); and commercial farms using modern irrigation technology (39 percent of total irrigated area); and 2) publicly owned irrigation schemes (18 percent of total irrigated area) that include national schemes managed by government or co-managed with farmers’ organizations; and institutional schemes managed by Regional Development Authorities and Agricultural Development Corporations, among others. Most infrastructure is old and dilapidated; investment is low due to insufficient financing and inadequate to meet the Governments Vision 2030 objectives. Increasing water availability for agriculture will require construction of more storage reservoirs, agricultural rainwater harvesting, direct use of wastewater, and exploitation of groundwater for irrigation (FAO 2015a).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Water Act of 2002 provided the framework for Kenya’s water use and management. It separated the management of water resources from the provision of water services, separated policy making from day-to-day administration and regulation, decentralized functions to lower level state agencies, and involved non-governmental entities in the management of water resources and provision of water services (Mumma 2005).

The Water Bill 2014, which repeals the 2002 Water Act, confirms the right to water; allocates responsibility to county governments for development and management of water services; distinguishes between national public works and county water infrastructure; transfer of assets, rights, liabilities, obligations, and agreements from Water Services Boards to either Country service providers or proposed Water Works Development Boards; licenses water service providers by a national regulator; provides water services on a cost-recovery basis; and envisions county-level water services providers (World Bank 2013; GoK 2014b). These structures are still very much in transition and are being actively debated.

Kenya’s 2010 Constitution calls for access to safe and sufficient water for all Kenyans as a basic human right, and assigns responsibility for water supply and sanitation provision to 47 newly established counties (World Bank 2013). The Draft Water Policy 2012 confirms these provisions in the Constitution and calls for equitable distribution of water and sanitation services, devolved/decentralized water services and optimization of self-financing (ESRC n.d.).

The irrigation sub-sector is governed by the 1966 Irrigation Act (Chapter 347) which is out of step with the 2010 Constitution which called for increased accountability and public service delivery at local levels. The 2015 Irrigation Bill proposes to repeal the Irrigation Act and align existing irrigation laws with the Constitution, specifically, county irrigation development units should be established within each county to: implement irrigation policy; formulate and implement county irrigation strategy; develop an irrigation database and integrate systematic monitoring and evaluation of the sub-sector; provide technical (surveys, designs, supervision of construction), financial and other support services; identify community-based smallholder schemes for implementation; undertake rehabilitation of existing irrigation schemes; build capacity of farmers and support establishment of viable farmer organizations to develop and manage irrigation schemes; participate in conflict resolution within irrigation schemes; and set up measures to implement adaptation and mitigation to climate change, all in line with standards and policy (GoK 2015b). It also proposes taking over small irrigation schemes (< 1,000 ha) from the national government; abolishing the National Irrigation Board; and creating a National Irrigation Development Service to assume the roles of the agency and absorb its staff (GoK 2015b, Business Daily 2015).

In addition, a 2015 Draft National Irrigation Policy is being prepared that will adopt principles of integrated water resources management, environment management plans, and agriculture water management strategy (FAO 2015a).

TENURE ISSUES

The Water Act of 2002 vests all rights to water in the State. Water users must acquire a water permit except for: (1) minor uses of water resources for domestic purposes; (2) use of underground water in places where there is no stress on the resource; and (3) use of water drawn from artificial dams or channels. Water is allocated by the WRMA, which establishes a regional office and appoints an advisory committee in each catchment area to advise on water resource management issues, including the allocation of permits. Irrigation water permits extend for 5 years. The rate is based on the amount of surface area to be irrigated (Mumma 2005; FAO 2005).

Community self-help water systems are registered under an informal registration system operated by the Ministry in charge of community development. These systems are not legal entities and operate outside the Water Act of 2002. Women and children are generally responsible for domestic water collection and management, but women are often not part of community water associations (Were et al. 2006; Mumma 2005).

The 2010 Constitution calls for devolution of powers and responsibilities for water and sanitation services delivery, but the sector has been slow in making headway. This is perhaps understandable as the draft policy was prepared in 2012 before the county governments came into being. However, the Water Bill 2014 was developed after county governments came into place and the same criticisms apply (Oyugi 2015; ESRC n.d.).

Water governance in the 2002 reforms was characterized by a division of powers and responsibilities between two levels of water resources management (national and river basin) and three levels for water service delivery (national, river basin, and district/municipal). The Water Bill 2014 largely retains this architecture and recycles the same institutions. It also centralizes decision making with the national government operating all apex bodies (the Water Resources Authority, the Water Harvesting Authority, the Water Services Regulator Board and Water Works Board). This approach does not allow for sufficient demand-side input into key sector decisions, nor does it support devolution so risks usurping or limiting the power of county governments. Other concerns related to this law include: omission of sanitation; failure to adequately distinguish functions and responsibilities at national and local levels; creation of multiple institutions whose roles are not clearly identified; and failure to articulate gender issues in the delivery of water and sanitation services (Oyugi 2015; ESRC n.d.).

Aligning legislation with the 2010 Constitution brings to the fore some important policy uncertainties: new institutional structures embodied in legislation and their roles and responsibilities; promoting real devolution to county level government; mechanisms to charge for water; and the future of water services boards. To address these concerns the government has three options to consider: a) maintain the status quo as stipulated under the Water Act 2002 (regional Water Services Boards as asset holding authorities); b) create a single national entity responsible for national public works and investment in water services; or c) devolve country-level investment functions to the county level. Regardless of the option chosen, past experience has shown that processes are likely to take a long time to implement; the matter of asset transfers is immediate particularly with regard to how new infrastructure is funded (Heymans et al. 2013).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Environment, Water and Natural Resources is the successor to three Ministries: Ministry of Water, Ministry of Wildlife and Forestry, and Ministry of Environment & Mineral Resources. It does not have responsibility over mining which falls under the authority of the Ministry of Mines, and irrigation which falls under the authority of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries (MALF). The Ministry is responsible for policies and programs aimed at improving, maintaining, protecting, conserving and managing the richness of Kenya’s natural resources including water, forestry, wildlife and environment. It is also tasked with ensuring good access to clean, safe, adequate and reliable water supply. It includes oversight of the Kenya Water Institute, Lake Basin Development Authority, National Water Conservation and Pipeline Corporation, Tana and Athi River Development Authority, Water Appeals Tribunal, Water Catchment Conservation Agency, Water Resources Management Authority, Water Services Board, Water Services Regulatory Board, and Water Services Trust Fund.

Overall responsibility for irrigation water management lies with the MALF, replacing the former Ministry of Water and Irrigation. Within MALF, the Irrigation and Drainage Directorate (IDD) is responsible for the coordination of irrigation and specifically smallholder irrigation. The National Irrigation Board formed in 1966 through the Irrigation Act (cap. 347) is responsible for the development of national irrigation schemes and the promotion of smallholder irrigation. Six Regional Development Authorities (RDAs), based on the main river basins of the country, have responsibility to plan, coordinate, and promote investment for integrated natural resource use, including irrigation projects. There is therefore duplication between the MALF and the RDAs (FAO 2015a).

The Water Resources Management Authority (WARMA) is responsible for allocation of water and delivery of water permits. The 2010 Constitution devolves planning and implementation to local counties at least for the projects they finance but this is not yet fully in place (FAO 2015a).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The government is aligning its legal framework governing water with the Constitution, while also adjusting its institutional framework to devolve more authority to newly formed county governments.

Kenya is making progress with improving access to clean water and sanitation. In 2015, 63 percent of the population had access to improved drinking water (82 percent urban versus 57 percent rural) and 30 percent to improved sanitation facilities (31 percent urban versus 30 percent rural) (World Bank 2016a). While the Constitution commits to safe and sufficient water as a basic human right, rapidly expanding clean water for all Kenyans poses a huge challenge given Kenya’s increasing water scarcity and population growth. Forward progress will require governors and county leadership to aggressively drive reforms and decentralization, increasing the role of well-performing water companies, expanding financing for water service provision, and increasing accountability and compliance—all with some urgency and at risk of supply disruption (Heymans et al. 2013).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Numerous public and private foundations are working to expand clean water and sanitation services for the poor and expanding water supply in urban and rural areas including the Water Project, Water.org, WaterAID UK, Charity:Water, Blue Planet Network, Lifewater, Project Humanity and Water4, among many others.