Published / Updated: May 2011

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

Nicaragua’s tumultuous political history reflects the dramatic impacts that differing perspectives on property rights and resource governance can have on the structure and performance of societies and economies. The Somoza regimes that governed Nicaragua from 1936 to 1979 emphasized the primacy of private property rights and the pursuit of an export market-oriented, large-scale commercial agriculture. These policies resulted in an economy in which rural land ownership was concentrated in the hands of relatively few Nicaraguans who operated farms producing coffee, cotton, sugar, tobacco, and beef for export, largely to the United States. This success, however, was accompanied by high rates of rural landlessness, low productivity in the small-farm food sector, and the emergence of stark inequalities of income and opportunity within the Nicaraguan population. The Sandinista government (1979–1990) reversed these policies, expropriating large landowners’ property for redistribution to cooperatives and smallholders and for use as state farms oriented toward food production for domestic markets. This move toward national self-sufficiency – combined with a reorientation of trade patterns toward Eastern Europe, Cuba, and other socialist countries – was more inclusive but did not provide a path to more equitable prosperity. Incomes declined and poverty levels climbed throughout the 1980s. During its seven-year tenure (1990–1997), the democratically elected government of Violeta Chamorro attempted to chart a middle path by adopting policies that protected the rights of land reform beneficiaries while also recognizing the rights of the landowners dispossessed by the reforms. These competing policies resulted in a plethora of competing claims, undermined land tenure security, and limited much-needed investment in the agriculture sector.

Successive Nicaraguan governments have made efforts to strike the appropriate balance between (1) promoting greater investment in economic growth through private ownership and management of property, especially agricultural lands; and (2) realizing greater social justice, including provision of more equitable and secure access to land by the poor and vulnerable. Some progress has been made. However, Nicaragua remains a highly inequitable lower middle-income economy, with the lowest 20% of the population holding less than 4% of national income and 39% of rural households estimated to be landless. Poverty is largely a rural phenomenon, with two-thirds of the rural population living below the poverty line.

External support is critical to both the Government of Nicaragua (GON) and to the prospects of poor, rural Nicaraguans, especially those indigenous groups living in the thinly settled and remote areas of the Atlantic coastal region. Donors provided an average of 18% of Nicaragua’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as official development assistance from 2000–2008, down from a high of 72% in 1991. This official development assistance constitutes a significant share of the government’s budgets in key sectors, including water, environmental protection, and health. External support also comes through private channels. Remittances from Nicaraguans living abroad, largely in Costa Rice and the US, are estimated to supplement the incomes of 40% of Nicaraguan households, with over US $1 billion flowing into the country in 2008. In addition, the US-Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) provides expanded opportunities for Nicaragua to export agricultural, fisheries, and manufactured products to the United States.

Donor governments and international financial institutions have explicitly supported continued strengthening of the property rights systems in Nicaragua, funding several projects for land administration, titling, and the regularization of documents regarding land rights over the last two decades. The process is slow, however, and most Nicaraguans still lack clear tenure rights. Donors and international environmental organizations have also contributed to conservation of the forest and biodiversity resources of Nicaragua with substantial funding and have worked to ensure the rights of indigenous groups in the Atlantic coastal region. Disaster recovery assistance has also been provided, particularly after Hurricanes Mitch and Felix.

With such support, Nicaragua’s economy has made slow but fairly steady progress since the late 1990s. Analysts point out, though, that Nicaragua can only increase its economic competitiveness – and jobs and incomes for the poor – if the government directs greater attention to agricultural modernization and the resolution of continued uncertainties regarding land. And others note that the unique and extensive environmental resources of Nicaragua – its forest resources, in particular – may be irreversibly threatened by illegal logging and unsustainable uses for agriculture and ranching. Mining operations in some areas have also resulted in deforestation and in water contamination.

National and local leadership face the challenge of developing a vision for Nicaragua’s future that is shared by the majority of the population, provides for their inclusion in the economy, and also generates a path of economic progress sufficient to pull them out of poverty. There is broad consensus that more secure rights to land and water, sustainable approaches to utilization of Nicaragua’s abundant natural resources, and a structure of democratic governance that ensures fair and equitable outcomes for the population as a whole are all needed to realize this vision. Donors and international organizations can help to support this vision, but only the political leaders of Nicaragua can develop the policies and institutions that will make its achievement possible. As USAID expands its partnership with Nicaragua in the context of the Feed the Future initiative, there will be new opportunities to address these critical governance dimensions of poverty, agriculture, and food security as well as the technology and resource-related issues.

Key Issues and Intervention Opportunities

Increasing access of poor rural households to arable land may be the most direct way to improve their food security status, but there is some evidence that providing access to land should be accompanied by the provision of a bundle of complementary inputs and training and access to markets if it is to have the desired impact. Further, the legacy of appropriate documentation for land rights – whether individual or collective – must also be addressed. Perceived tenure security reportedly varies by individual or group based on a variety of social, economic, and political factors, as well as the specific historic context. There is wide agreement, however, that insecurity inhibits productivity-enhancing investments. USAID and other donors seeking to increase food security and reduce poverty in rural Nicaragua might consider focusing on particular regions of the country, where integrated approaches to increasing smallholder and landless rural households’ access to land and water, improving tenure security, and agricultural development offer the greatest potential for impact.

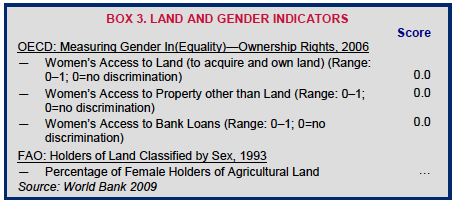

Within such integrated initiatives providing access to land and complementary inputs, specific attention should be directed to improving tenure security for rural women. Assigning land rights to women enhances the impact of land access on household wellbeing, yet women continue to experience greater tenure insecurity and more restricted access to land than is experienced by men. Donors could support initiatives to ensure that women do not face discrimination in terms of the amount or quality of land they receive, and could improve tenure security for rural women by reducing costs associated with obtaining legal title.

Many low-income families in Nicaragua have acquired land through informal markets. In some cases, multiple claims to this land threaten investments (housing, land development) that have already been made. Processes to regularize the ownership of municipal land have been launched in major towns, such as the Millennium Challenge Corporation and World Bank projects in Leon, but are not complete. Moreover, governance issues have arisen to call into question the will of the Government of Nicaragua to respond to the needs of low-income residents. Donors may also wish to consider ways to link expansion of property rights with the development of credit markets and other financial mechanisms, land banks, and community participation mechanisms – all of which should be integrated with ongoing cadastral and titling initiatives.

The 2007 Water Law attempts to clarify and reorganize the roles of the government branches, independent agencies, users’ organizations, and territorial administrative agencies in the water sector but delays in creating the National Water Authority (ANA) are impeding its effective implementation. Disputes persist between the state-owned water company (ENACAL) and the Emergency Social Investment Fund (FISE) over who is in charge of providing water and sanitation services in rural areas. This uncertainty affects the sector’s ability to move forward in a strategic manner, constraining donors from pursuing a sector-wide approach. Staffs recommend the development of a national unified strategy for water and sanitation with particular focus on establishing a clear institutional and legal framework, with special attention to rural areas. In the case of the Atlantic Coast regions, where construction costs are high, raising access to water and sanitation also will require investment in local capacity building. USAID and other donors play a very large role in the provision of funding for the water sector in Nicaragua. Efforts need to be initiated to build the capacity of the Government of Nicaragua, including the ANA, to prioritize, sequence, and finance needed actions to implement the law in a realistic timeframe, focusing on institutional development, enforcement, budgeting, and cost recovery.

Deforestation in Nicaragua is occurring at an alarming rate, with widespread illegal logging driving the decline. Although the GON has decentralized management of the forestry sector and progress has been made, decentralization has faced many obstacles, including budget problems, lack of local authority over logging and the use of forest resources; centralist and bureaucratic GON tendencies, corruption, and the lack of skills and experience of many local governments. USAID and other donors could support efforts to resolve legal contradictions and ambiguities that hinder good governance of forestland and forest resources; help the GON clarify the rights and jurisdiction of municipal authorities through refinement and revision of legislation; promote grassroots organization and mobilization around local and sustainable forest management; and provide all stakeholders with incentives and rewards for good local management.

In the Atlantic region, indigenous rights to land and forests face pressure from interests seeking to exploit forestland and products. In partnership with other donors and implementing organizations, USAID has helped indigenous communities demarcate territory, conduct forest inventories, and create management plans that include identification of forests for conservation and for sustainable harvesting and marketing of certified wood and other forest products. Experience from countries such as Mozambique has taught that such efforts can bring significant benefits to local communities and governments but they require substantial and continuing commitments of effort, time, and resources at local levels. USAID and other donors could support the extension of project activities throughout the Atlantic region. Donors could also help the GON draft legislation providing further clarity regarding indigenous rights to land and natural resources and establishing processes and procedural safeguards to ensure that local communities are able to negotiate meaningfully and effectively with commercial interests for exploitation of those natural resources.

Summary

Different perspectives on property rights and resource governance have driven conflicts and political change in Nicaragua over the last 40 or 50 years. Successive governments have introduced radical changes of direction in economic policy, although in recent years a pragmatic combination of approaches seems to be in play. The Somoza regime that ruled the country from the 1930s to 1979 emphasized private property rights and relatively capital-intensive agricultural development, the result of which was a highly inequitable distribution of rural land. Large landowners built a relatively productive, export-oriented farming sector based on coffee, livestock, sugar, cotton, and tobacco in the most fertile lands in the western Pacific region of the country, drawing in a large pool of rural landless labor. The productivity of the smallholder food sector lagged as these farmers were displaced on to more marginal lands more distant from markets and services. When the Sandinistas took power in 1979, they initiated land reforms and the agricultural system reoriented toward food production. The government expropriated large agricultural properties and distributed them to the landless, especially through the mechanism of farmer associations or cooperatives, or established state farms. Agricultural productivity declined, however, as newly established state farms, cooperatives, and independent farmers struggled to establish operations while anti-government factions pursued aggressive and destructive attacks in the rural areas. The ouster of the Sandinista government in 1990 by the political alliance headed by Violeta Chamorro resulted in the reversal of some aspects of the land reforms: expropriated landowners were permitted to claim restitution for their properties and the rights of poor and landless farmers to land distributions was affirmed. These competing principles resulted in a significant number of land disputes and high tenure insecurity. Subsequent governments have been faced with persistent confusion and uncertainty over property rights, and have made little progress in finding sustainable solutions to reducing inequities of land access and ownership, increasing tenure security, or managing Nicaragua’s abundant land, water, and forest resources effectively. Agricultural productivity has, however, been rising after 1990, in spite of periodic hurricanes that wreaked havoc on rural areas (Hurricane Mitch in 1998 and Hurricane Felix in 2007).

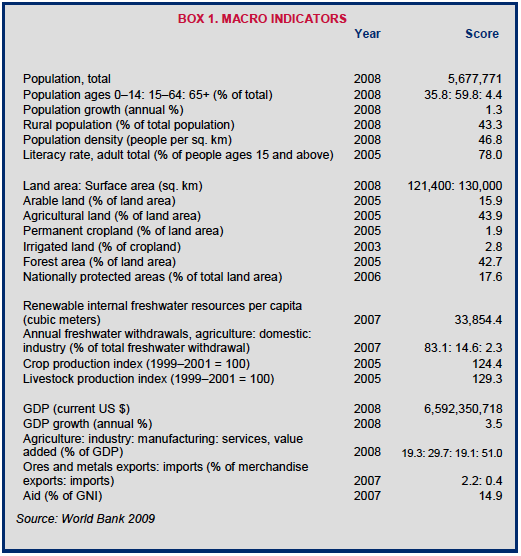

Still, Nicaragua is one of the poorest countries in Latin America, with an economy dominated by service industries and almost 60% of its six million people resident in cities. Urbanization has been occurring at an average annual rate of 1.8% (2005–2010), and over 25% of the population lives in the capital, Managua. Overall, however, Nicaragua, Central America’s largest country, is not densely settled. The Central region is an ecologically active area with mountains and ranges, with massive cloud forests as well as coffee plantations. The Atlantic lowlands, a tropical region in which many indigenous ethnic groups maintain ancestral lands, is the largest and least densely populated area, with poor soil and few roads and other services to connect it to the urban centers of the Pacific region.

Still, Nicaragua is one of the poorest countries in Latin America, with an economy dominated by service industries and almost 60% of its six million people resident in cities. Urbanization has been occurring at an average annual rate of 1.8% (2005–2010), and over 25% of the population lives in the capital, Managua. Overall, however, Nicaragua, Central America’s largest country, is not densely settled. The Central region is an ecologically active area with mountains and ranges, with massive cloud forests as well as coffee plantations. The Atlantic lowlands, a tropical region in which many indigenous ethnic groups maintain ancestral lands, is the largest and least densely populated area, with poor soil and few roads and other services to connect it to the urban centers of the Pacific region.

Forty-six percent of the population lives below the poverty line and 15% live in extreme poverty. These rates are higher in rural areas where, at 68%, the incidence of poverty is more than double that of urban areas (29%). Rural poverty is associated with access to land. Nine percent of landowners control 56% of the farmland, while 61% of the smallest farmers hold only 9% of the land area. In addition, 38% of the rural population are landless. Twenty-nine percent of the urban population live in poverty and many rural-urban migrants live in informal settlements on the urban periphery. These settlements lack infrastructure and basic services, but have continued to grow because low-income households lack access to other land. Residents of such settlements are sometimes subject to eviction. Women-headed households are more likely to be poor than are male-headed households.

Roughly 20% of agricultural land in Nicaragua is owned by women – a result of proactive efforts to improve women’s land rights through land distribution and titling programs. The formal law supports the equal rights of women and men to inherit, own, and manage economic assets, and researchers have found some gains in women’s decision-making authority over land and its production. Overall, however, custom and practice continue to support the dominance of men in accessing and controlling land and its production. Those women who do own land are often unable to protect their rights against challenge and face barriers to obtaining credit for investment. The rate of Nicaraguan women living in poverty is increasing.

Nicaragua has abundant water resources from both rainfall and groundwater. However, Nicaragua’s water supply suffers from extensive pollution and almost all rivers and lakes are contaminated. Untreated domestic and industrial waste is frequently disposed into water sources and while overall about 79% of the population has access to improved water sources, only 35% of the rural population has such access. Few regulations or legal mechanisms exist to stem the disposal of wastewater into water sources.

Nicaragua’s extensive forests cover 43% of the land area, but are threatened by legal and illegal logging, fuelwood collection, and clearing for agriculture. Deforestation is occurring at a rate of 1.3% per year. The forestry sector accounts for less than 1% of GDP, but tourism, which provided about 3% of GDP in 2006, relies heavily on Nicaragua’s forests and is expected to grow to 5% in the 2007–2016 period. However, despite the potential for growth, the sector has historically not received the attention of policymakers. Other challenges to the forestry sector include lack of coordination among government authorities, ill-defined institutional responsibilities, and lack of interest in sustaining forest resources within local communities.

The mining sector contributes about only 1% of Nicaragua’s GDP, most of which is attributed to gold mining. The sector is expanding through expansion and upgrading of existing operations and exploration for additional mineral deposits. Despite its relatively small economic contribution, gold mining has had significant negative consequences in terms of deforestation, water pollution, and damage to health, and has created conflict between mining interests and local communities. Nicaragua has unproven petroleum reserves currently under exploration off the Atlantic coast.

Land

LAND USE

Nicaragua is the largest country in Central America, occupying 121,400 square kilometers. The country is bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south, west by the Pacific Ocean, and east by the Caribbean Sea. The country has three regions: (1) the Pacific region (15% of total territory) with fertile plains, two large lakes, and the largest cities, including the capital, Managua; (2) the Central region (30% of land mass), with mountainous terrain and some small valleys with medium fertile soil; and (3) the Atlantic region (55% of territory), with a flat wooded topography, rich in forests and mineral deposits but with generally poor soil. The Caribbean coast, also known as the Mosquito Coast, is vulnerable to severe tropical storms and frequent hurricanes. The country also has dormant and active volcanoes and is prone to earthquakes. Forty-four percent of total land area is agricultural, 16% is arable land, 2% is permanent cropland, and 43% is forest, including the largest tract of rainforest north of Amazonia. Approximately 18% of all land lies within nationally protected areas (FAO 2000; World Bank 2009a).

Of Nicaragua’s 5.7 million people (2008), 43% live in rural areas and 57% live in urban areas. Approximately 23% live within nationally protected areas. Most of the population lives in the Pacific region in the lowland area between the Pacific Ocean and Lakes Managua and Nicaragua. While Nicaragua is generally characterized as a multiethnic nation, approximately 10% of the population of Nicaragua is considered to be indigenous. The majority of Nicaragua’s indigenous peoples – Miskitu, Creole, Mayangna, Garífuna, and Rama – live on ancestral land in the Atlantic region, which is recognized as indigenous territory subject to limited self-rule and divided into the Autonomous Region of the North Atlantic Region (RAAN) and Autonomous Region of the South Atlantic Region (RAAS). More than a million Nicaraguans live abroad, primarily in the United States and Costa Rica (World Bank 2009a; World Bank 2003; Orzco 2003).

Nineteen percent of Nicaragua’s 2008 GDP of US $6.6 billion was derived from agriculture, 30% from industry, and 51% from services. The agricultural sector employs 45% of the country’s workforce. About 75% of agricultural production is for domestic consumption. The primary consumption crops are beans, rice, and maize, which account for 63% of the cropped area and about 55% of the total value of agricultural production. Most families also keep some livestock, primarily cattle, poultry, and pigs. The commercial farming sector produces coffee, meat, sugar, sesame, and tobacco for export. Coffee accounts for 22% of the value of agricultural production, followed by sugar cane (11%). Nicaragua is the principal producer of ethanol in Central America. Nicaragua’s first coffee plantations were developed in plains of the Pacific region but most production is now concentrated in the Central region’s northern mountains, which have rich volcanic soils and a tropical climate. The agricultural sector is characterized by low productivity. In 2009, Nicaraguans received almost US $1 billion in remittances from abroad, the majority from the United States. Remittances provide essential income to 40% households (IADB 2009c; WTO 2006; USDOS 2011; World Bank 2009a; Orzco 2003; IFAD 2010; ILC and CISEPA 2011).

Nearly half of Nicaraguans (2.4 million) live below the poverty line; 15% (766,000) in extreme poverty. Between 1993 and 2005, the numbers of poor families have remained roughly the same. Poverty is twice as high in rural areas (68%) as in urban areas, and 80% of extremely poor households are rural. The poorest areas are in the central northern region, in the departments of Esteli, Jinotega, Matagapa, and Nueva Segovia. The poorest rural households are those with little or no access to land, a condition that affects an estimated 38% of rural households. Women-headed rural households, which comprise about one-fifth of all rural households, are among the poorest (Wiggins 2007; UN-Habitat 2005a; World Bank 2010c).

Nicaragua’s urban population is growing at an annual rate of 1.8% (2005–2010). Much of this growth is attributed to migration from rural areas, particularly to the capital, Managua. Twenty-nine percent of the urban population lives in poverty and many rural-urban migrants live in informal settlements on the urban periphery. These settlements do not conform to urban development regulations and regulations governing housing units; both physical infrastructure and services are inadequate and the settlements are spatially and socially segregated from other communities (EoE 2009; Merrill 1993; UN-Habitat 2005a).

Deforestation, soil erosion, and water pollution are significant problems in Nicaragua. Deforestation averages approximately 1.3% annually, while agricultural runoff – including pesticides, animal waste and large amounts of soil – pollutes aquifers. The conversion of forests to agricultural land (for commercial agriculture and cattle pastures) and unregulated logging also contribute to deforestation. Excessive and ineffective use of pesticides to control malaria, along with widespread agricultural use of pesticides, has resulted in extensive environmental contamination. Pollutants have devastated water supplies, disrupting the population’s drinking supply as well as damaging the country’s forests and wildlife (USACE 2001; USFS 2009).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Since pre-colonial times, the fertile lowlands along Nicaragua’s Pacific coast have attracted settlers, and elites with financial resources and political influence controlled large amounts of agricultural land. During the period of colonization by the Spanish, some indigenous communities migrated east while others remained, providing farm labor and supporting services. The eastern Atlantic region was invaded by Great Britain, but the colonial power made little effort to colonize the indigenous people, who depended on the region’s extensive forest, ocean, and river resources for their livelihoods. The Atlantic region attracted white settlers, who brought their African slaves with them to the region, and Afro-Caribbean workers migrated from Jamaica and Belize – resulting in an ethnically diverse culture. In 1894, with the support of the US, the Nicaraguan military invaded the region, imposing the western Mestizo culture and seizing control of natural resources. The Nicaraguan government sold foreign companies licenses to mine and log the area (URACCAN n.d.; Broegaard 2009).

Following Independence and the establishment of Nicaragua as an independent republic in the early 1800s, successive governments have implemented agricultural land policies reflecting their differing political philosophies. From 1939 to 1979, the Somoza regimes emphasized the primacy of private property rights and the pursuit of an export market-oriented, large-scale commercial agriculture. A relatively small number of large landowners operated large commercial farms, producing products for export. The Somoza family itself held an estimated 20% of the land. At the other end of the spectrum, the majority of the rural population had small subsistence farms characterized by low productivity or were landless (URACCAN n.d.; Broegaard 2009).

The Sandinista government (1979–1990) instituted land reforms, expropriating an estimated 35% (450,000 hectares) of land held by large landowners and redistributed it to: cooperatives, which received 40% of redistributed land; newly formed state-owned agro-industrial companies (34% of the redistributed land); and landless farmers (26% of the redistributed land). In the Atlantic region, the government passed the Autonomy Law (1987), which gave indigenous people formally recognized rights to their land and other natural resources and the right to limited self-rule. Overall, the Sandinista government’s efforts to achieve more equitable prosperity through land redistribution was unsuccessful: incomes declined and poverty levels climbed throughout the 1980s. In the Atlantic region, settlers, migrants, and foreign commercial interests have continued to seek rights to indigenous land and natural resources, often successfully (URACCAN n.d.; Broegaard 2009; COHRE 2003; Deininger et al. 2003).

The electoral defeat of the Sandinista government in 1990 led to a second era of land reform. The Chamorro government restored the rights of landowners whose land had been confiscated by the Sandinista government. At the same time, the GON promised the poor that they could keep their newly acquired land. The contradictory policies gave rise to competing land claims, tenure insecurity, and conflicts. Land ownership again became highly concentrated in areas where large landowners successfully asserted their prior rights and dispossessed beneficiaries of the Sandinista reforms. During this period, agricultural productivity only gradually improved because insecurity of tenure adversely affected investments in both export and food crops (Broegaard 2009; COHRE 2003; Deininger et al. 2003).

Land ownership in Nicaragua continues to be highly concentrated. Seventy-two percent of rural households hold only 16% of total land, with landholdings of 3.5 hectares or less. Twenty-eight percent of rural households hold 84% of all land. Ten percent of farms are over 35 hectares. Thirty-eight percent of the rural population is landless. The Gini coefficient for land concentration is 0.86 (2003 data). The high number is due to the presence of a number of very large holdings. The value of the coefficient is similar to those found in other Latin American countries, but is significantly higher than, for example, that of Asian countries that also underwent processes of land redistribution and which generally have Gini coefficients of around 0.4 (Broegaard 2009; Deininger et al. 2003; World Bank 2003).

Urban land distribution and human settlements are increasingly characterized by social and spatial segregation and exclusion of the poor, resulting in the development of enclaves. About 25% of the population lives in Managua, where, as in other urban areas, lack of land and affordable housing has led residents and new migrants to the area to develop informal settlements. These informal settlements have long developed in areas generally unsuitable for urban development due to environmental problems. More recently, migrants from rural areas have begun occupying land more suitable for urban development. The informal settlements lack infrastructure and basic services but have continued to grow as urbanization continues (UN-Habitat 2005b; FSD 2007).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution of Nicaragua (1987, as amended) guarantees the right to private property. Article 108 guarantees land ownership to all owners who use their land productively and efficiently, but Article 44 preserves the government’s right to limit property rights to accomplish the ―social function‖ of property (GON Constitution 1987).

Nicaragua’s 1904 Civil Code, as amended, governs real property in Nicaragua and provides the framework for the classification of land and land tenure types, including ownership and leaseholds. The GON has also passed, amended, and often repealed dozens of laws implementing land reforms in the period from 1979–2002. Primary among them is the Law on Agrarian Reform (1981, as amended), which governed the process of expropriation of idle or underutilized land and distribution of land to individual farmers and cooperatives. More recent legislation includes the 1999 Law on the Regularization/Organization/Titling of Spontaneous Human Settlements, which provides for some residents of informal settlements in urban and peri-urban areas to receive title to their plots (COHRE 2003; Martindale-Hubble 2008; Rogers 2009; Larson 2008).

Articles 89–91 of Nicaragua’s Constitution recognizes the rights of communities in the Atlantic region to: preserve and develop their cultural identity; to hold land communally; to establish their own forms of social organization; and to use and enjoy the water and forest resources on their land. The Statute of Autonomy of the Atlantic Coast (1987) and the Communal Land Law (2003) provide for the rights of indigenous people to own and use communal lands and the water and forests based on their traditional and customary patterns of land and resource use and occupancy. The 2002 Demarcation Law Regarding the Properties of the Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Communities of the Atlantic Coast, Bocay, Coco and Indio Maiz Rivers authorizes indigenous communities to demarcate their territories and assert rights to the natural resources within those boundaries (GON Constitution 1987; Larson 2008; Anaya and Williams 2001).

The Coastal Law (2009) provides a framework for environmental protection, public access rights, commercial activity, and property rights along the shoreline of any body of water in Nicaragua. For coastal property along the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the law establishes environmental and public access requirements. It recognizes beachfront property rights within this area, but gives municipalities zoning authority. There is a five-meter setback, measured from the high-water mark, for natural lakes, artificial lakes, rivers, and other bodies of water. The law establishes a Commission for Coastal Zone Development (CDZC) to provide technical assistance and advice to municipalities on coastal development and management, and on concessions for use of public land (Rogers 2009).

In 2001, the GON adopted the General Policy for Territorial Ordering, which is designed to support the decentralization of authority over land administration to local levels. Under the policy, municipalities are responsible for drafting land management plans that include: (1) a municipal land policy leading to sustainable development; (2) a proposal to guide land uses; and (3) proposed measures and implementation guidelines to settle disputes related to urban and rural land management. The policy is consistent with the General Law on the Environment, which gives municipal authorities the responsibility for formulating land use plans. Despite these pronouncements, decentralization of authority over land use planning has been slow, in part due to the history of control exercised by centrally driven agencies (Larson 2004; UN-Habitat 2005b).

TENURE TYPES

Nicaraguan law recognizes five land classifications: national or state land, private land, communal land, protected areas, and ejidal land:

-

- National or state lands are defined as any lands that have not been transferred to private individuals, groups such as cooperatives and associations, or are not part of communal indigenous lands.

- Private lands are owned by individuals, groups such as cooperatives, or corporations. In order to receive the benefit of private ownership rights under the law, private land must be registered.

- Communal lands are defined by the Communal Land Law (2003) as those formally recognized as the communal property of indigenous and ethnic communities in a manner consistent with that law.

- Protected areas are designated by the GON as areas whose purpose is to preserve, manage, and restore plant and animal wildlife and other life forms, as well as the biodiversity and the biosphere.Protected areas include national territory that, by being protected, allows the state to restore and preserve geomorphologic phenomena and other sites of historical, archaeological, cultural, scenic, or recreational importance. The state may designate national, private, or communal property as protected areas.

- Ejidal land is land owned by municipalities. Ejidal land is considered communal land; municipalities can control the use of ejidal land. Ejidal land can be leased but not sold (UN-Habitat 2005b; Broegaard 2009; GON Civil Code 1904).

Land tenure types in Nicaragua are:

- Ownership. Land owners – individual or collective – have the right to use their land, to exclude others from the land, and to transfer the land. Ownership rights are subject to the state’s right of expropriation and use of land is subject to GON land use planning. Countrywide, 81% of landholders identify themselves as landowners.

- Leasehold. Nicaragua’s formal law permits leaseholds. The terms of leaseholds, including the length of time and permissible land uses, are governed by the agreement of the parties. An estimated 6–15% of land in Nicaragua is leased, with slightly higher percentages in urban areas.

- Informal occupation. Occupation of informal settlements is a common tenure type in urban and peri-urban areas. Occupation of informal settlements is considered contrary to formal law and occupants are subject to eviction. An estimated 34% of urban plots are in informal settlements (GON Civil Code 1904; COHRE 2003; Broegaard 2009; de Janvry and Sadoulet 2002).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Nicaraguans access to land through purchase, inheritance, government land programs, and rental markets. As of 2002, 46% of plots were reportedly acquired through land sales, 21% through inheritance, 16% through land reform programs, and 15% through rental markets this rental figure is high by some other accounts. The extent to which the statistics report on urban or rural land or both is unknown. Land can also still be acquired through the principle of ―first clearing‖ of land, but such development is often on indigenous land. Under the Foreign Investment Law (Law No. 344 of 2000) foreigners are permitted to own land in Nicaragua under the same conditions as nationals and access land through the land sale and rental markets (Broegaard 2009; de Janvry and Sadoulet 2002).

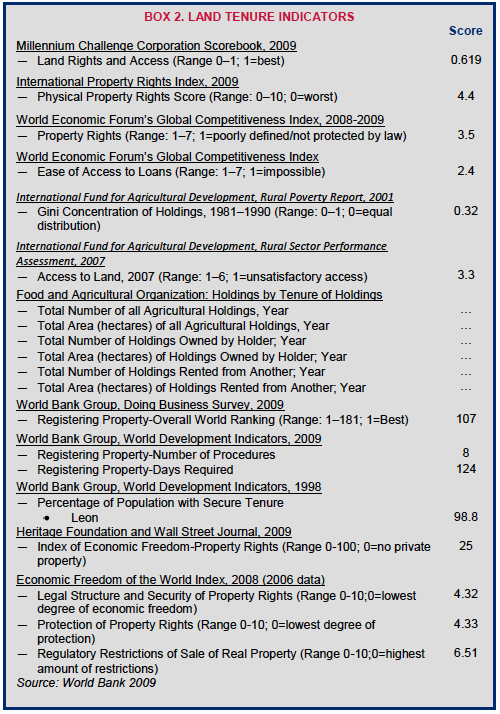

The security of private property rights in Nicaragua have been undermined by inadequate documentation of rights. As of 2005, more than half of all Nicaraguans households had inadequate documentation of their ownership rights. The land reforms of the 1980s were carried out by the government with documentation that fell short of guaranteeing clear title. Tenure security is also impacted by contradictory policies implemented after 1990 regarding rights to the 28,000 private properties that were seized during the Sandinista regime (1979–1990) and redistributed to landless people or smallholder farmers. The Chamorro government invited dispossessed landowner to apply for restitution of their lands, while also pledging to recognize the rights granted to poor and rural households during the reform period. As a result, there are many plots of land for which multiple ownership documents have been issued and these have been subject to competing land claims. Recent government efforts to dismiss claims outright through retroactive application of decrees legalizing the confiscation and by dismissing claims as settled by creating escrow accounts without agreement as to the amount of compensation have fueled continuing controversy (Broegaard 2009; USDOS 2011; USDOS 2010a).

Poor enforcement of property rights has limited both foreign and domestic investment, especially investment in real estate development and tourism. The court system is widely believed to be corrupt and subject to political influence. Establishing verifiable title history is often entangled in legalities relating to the expropriation of 28,000 properties by the Sandinista government in the 1980s. Nicaraguan authorities seldom challenge illegal property seizures by private parties, which are occasionally undertaken in collaboration with corrupt municipal officials (Broegaard 2009; Deininger et al. 2003).

As of 2005, more than half of Nicaraguan households had untitled or unregistered lands and overlapping titles were still a problem. In addition, many land reform beneficiaries believe their rights to be insecure because they depend on collective title, even when that title is legally sound and registered (Broegaard 2009).

In spite of this tenure insecurity, there is a high level of home ownership in Nicaragua, especially in urban areas. For example, 87% of households own their homes in Managua, while only 3% rent. Women in urban areas own 52% of homes. However, land tenure is insecure in low-income, informal urban settlements due to legal irregularities. In some areas, the local government has evicted residents and destroyed informal settlements to allow for new construction and has not made adequate provision for substitute housing (UN-Habitat 2005b; COHRE 2003).

Land registration requires eight procedures, an average of 124 days, and payment of 3.9% of the property value. Despite the costs in time and money, there is a high demand for more secure property rights in Nicaragua, and possession of a registered title is perceived as providing tenure security. In the case of untitled land, a landholder’s perceived tenure security depends upon the policies, actions, and opinions of the local farming community, the agricultural cooperative, and the mayor or other high-ranking civil servants. Informal rights to purchased land are usually considered secure with a written sale agreement, certified by a lawyer or by witnesses to the transaction (World Bank 2011; Broegaard 2009; UN-Habitat 2005b).

Land registration requires eight procedures, an average of 124 days, and payment of 3.9% of the property value. Despite the costs in time and money, there is a high demand for more secure property rights in Nicaragua, and possession of a registered title is perceived as providing tenure security. In the case of untitled land, a landholder’s perceived tenure security depends upon the policies, actions, and opinions of the local farming community, the agricultural cooperative, and the mayor or other high-ranking civil servants. Informal rights to purchased land are usually considered secure with a written sale agreement, certified by a lawyer or by witnesses to the transaction (World Bank 2011; Broegaard 2009; UN-Habitat 2005b).

Grassroots movements to reform land legislation have accomplished two major victories for indigenous land rights. In 2001, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights – the highest tribunal in the Americas – held that the Mayangna community of Awas Tingni had customary rights to their property and the GON violated these rights by granting concessions to a foreign lumber company. In a second 2001 case, the same court ordered the GON to title the Awas Tingni’s lands. The ruling in Mayagna (Sumo) Community of Awas Tingni v. Nicaragua is the first instance in which an international tribunal with legally binding authority has found a government in violation of the collective land rights of an indigenous group, setting an important precedent for the rights of indigenous peoples under international law (University of Arizona 2009; COHRE 2003).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Nicaraguan women head 28% of rural households and 39% of urban households, provide approximately 40% of the agricultural labor in the country, and are usually responsible for rearing and marketing small livestock. Nicaraguan women have benefited from the country’s land reforms: they own approximately 20% of the country’s agricultural land and the number of women obtaining title to land – either individually or jointly with their spouse – is increasing (Lastarria-Cornhiel et al. 2003; COHRE 2003; OECD n.d.; Ceci 2005).

Nicaragua’s formal law is generally supportive of women’s rights to access and control land and other assets. The Constitution grants equal rights to all citizens, prohibits gender-based discrimination, and provides that men and women have the same rights to inherit family-owned properties. Nicaragua’s 1959 Family Code stipulates that all property brought into or acquired during marriage be pooled, including income from those properties. In case of separation or divorce, all property and income are divided in equal shares between the spouses; and in case of death, half remains with the surviving spouse (UN-Habitat 2005b; OECD n.d.; Lastarria-Cornhiel et al. 2003; Ceci 2005).

Nicaragua’s land reform legislation attempted to improve women’s access and rights to land. The 1981 Agrarian Reform Act recognized women’s right to be direct beneficiaries of land allocations and did not apply the head of household criterion in its selection procedure. However, initial efforts to increase the number of women landowners through legislative support for joint titling were thwarted by combinations of male family members, such as fathers and sons and two or more brothers. Between 1979 and 1989, women accounted for about 10% of beneficiaries of land titles. In 1995, Law No. 209 established a legal presumption whereby titles held in the name of the head of the household would be extended to the name of the spouse or stable partner. The number of titles issued to women rose to 31% (Ceci 2005; Lastarria-Cornhiel et al. 2003).

Nicaragua’s land reform legislation attempted to improve women’s access and rights to land. The 1981 Agrarian Reform Act recognized women’s right to be direct beneficiaries of land allocations and did not apply the head of household criterion in its selection procedure. However, initial efforts to increase the number of women landowners through legislative support for joint titling were thwarted by combinations of male family members, such as fathers and sons and two or more brothers. Between 1979 and 1989, women accounted for about 10% of beneficiaries of land titles. In 1995, Law No. 209 established a legal presumption whereby titles held in the name of the head of the household would be extended to the name of the spouse or stable partner. The number of titles issued to women rose to 31% (Ceci 2005; Lastarria-Cornhiel et al. 2003).

Despite the legislative support for women’s land rights, significant challenges remain. While researchers identify a number of women asserting their rights within their households and communities to manage their agricultural land, customary norms and practices recognizing the male household head as the main authority figure and the principal property owner persist. Despite legislative reforms that give female spouses equal rights in marital property, in many households husbands have effective control over land and may not even consult their spouse when making decisions about the land. Wives often concede decision-making authority to their husbands, and in some cases women applying for credit through women’s programs have turned the money over to men for their individual use. Women also tend to face greater tenure insecurity than men. Women often lack funds to register their titles or to protect their land rights in court. The rate of women living in poverty is growing (Lastarria-Cornhiel et al. 2003; OECD n.d.; Ceci 2005; UN-Habitat 2005b).

While there is no formal prohibition against women accessing bank loans, discrimination is common and women have more difficulty borrowing and are typically granted a smaller sum than men. The number of private and public banks offering loans to women is growing, but about one-third of women in Nicaragua apply to microcredit institutions and NGOs, and many others rely on individual lenders to meet their credit needs (Lastarria-Cornhiel et al. 2003; OECD n.d.; Ceci 2005).

Recent reforms have sought to remedy this imbalance. In December 2010, the National Assembly of Nicaragua called for the creation of a fund, to be managed by Banco Produzcamos, which would provide credit to rural women for land purchase. The plan is to enable rural women to purchase up to 3.4 hectares of land for agricultural production. The program prioritizes women who are landless and heads of household (AWID 2010; Silva 2010).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Intendance of Property is the primary institution responsible for decisions regarding land and property. The Intendance is an autonomous institution that includes of several offices, including the Urban Titling Office and the Rural Titling Office, which are responsible for issuing titles following resolution of claims for indemnification or return of properties. The Nicaraguan Territorial Studies Institute (INETER) is an autonomous institution under the President of Nicaragua that is responsible for the physical cadastre in both rural and urban areas. The Public Registry, which is under the Supreme Court of Justice of the Judicial Branch, is responsible for maintaining land registration records. The Public Registry has offices in each department and in RAAN and RAAS. The Public Registry has been plagued with problems relating to the poor physical condition of records, inconsistencies and inaccuracies, and the manual filing system. The offices are being modernized (World Bank 2002; COHRE 2003; Broegaard 2009).

The General Policy for Territorial Ordering provides for the dispersal of land administration responsibilities across several institutions, including INETER; the Ministry of Natural Resources; the Ministry of Agriculture Livestock and Forestry; the Ministry of Development, Industry and Trade; and the Office of Property and Rural Titling. Municipal authorities have responsibility for formulating land use plans, with the Nicaraguan Institute for Municipal Development. However, decentralization of authority for land use planning to municipalities has been slow and the supporting institutional structures are not fully formed (UN-Habitat 2005b).

In 2007, President Ortega installed Citizen Power Councils (CPCs) at neighborhood levels throughout Nicaragua and identified CPCs as the government’s preferred civil society partner in implementing its economic and social agenda, including decisions on infrastructure development, local regulatory authority, and access to low-income housing. Civic leaders allege that CPCs are politically motivated and distinguish between government supporters and others in the delivery of benefits. On several occasions, CPC members have taken physical possession of property either through force or the threat of violence, and municipal officials, court officers, and Nicaraguan National Police have been unwilling to intervene in these cases. Constitutional experts, human rights activists, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have criticized the use CPCs because they are unelected, appear to operate outside the law, and displace NGOs (USDOS 2010a).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Nicaragua has a relatively active formal land sale market, but the market does not yet appear to be having the effect of increasing equitable distribution of landholdings and continues to be characterized by inequalities in wealth and power. Data on the land sales market suggests that, despite some participation in the market by small producers, the market is contributing to the re-concentration of rural land. Small farmers are especially vulnerable to risks resulting from legal uncertainty regarding land rights, price fluctuations, limited access to rural financial markets, and pressure from large landowners to sell. Studies suggest that many small farmers try to adopt a defensive strategy based on reduced consumption to retain their land but may ultimately be forced in distress sales. Most of the accumulation of land on the formal market has been by coffee and livestock producers. It is unknown whether the land purchasers are based in rural or urban areas, and the extent of foreign interests purchasing land is unknown (Ruben and Masset 2003; Deininger et al. 2003; Boucher et al. 2005; Broegaard 2005).

Many land sales occur on the informal market and are not registered. Registering the formal sale of land in the capital city of Managua requires eight steps: (1) the seller obtains a certificate and folio of non-encumbrance from the registry book; (2) the seller obtains a tax clearance certificate from the municipality; (3) a notary prepares and notarizes the public deed; (4) the parties obtain the Cadastre Certificate and valuation of the cadastre; (5) an inspector assesses the property value; (6) the income/transfer tax is paid to the Tax Administration Office within the Ministry of Treasury; (7) the notary inserts documents from the Office of Cadastre into the public deed; and (8) the parties file the public deed for registration at the Land Registry. Studies suggest that many small landholders are evidencing their transactions with written documentation of sale but foregoing registration in order to avoid the cost and time (World Bank 2011; Broegaard 2009).

The land rental market in Nicaragua is limited in terms of both participation and volume of land leased. Landless families are the primary lessees of land. Based on 1998 data, 23% of all agricultural producers rely on rental markets to access land and 18% of these are completely landless. Evidence also suggests that land rental markets, though far more active than before the reforms, are not significantly affecting the overall distribution of land (Deininger et al. 2003; Barham et al. 2004; Boucher et al. 2005).

Nicaragua’s mortgage market is small but growing. As of 2007, there were 8,150 mortgages for housing and the average mortgage was US $28,821. However, these mortgages tend to be only accessible to those with significant assets. The low savings capacity of small producers and the landless exposes them to significant uncertainty because of the high cost of legalizing rights to land and the lack of affordable commercial loans, most of which have high interest rates, low amounts and very short terms. However, microfinance organizations offer small loans to some agricultural producers and smallholders. These loans average US $745 and are accessible to lower-income households (Barham et al. 2004; Arenas 2007).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The Constitution of Nicaragua guarantees the right of private property, subject to the state’s right to expropriate property for purposes of social interest or public utility. Payment of fair compensation for the expropriated property is required. Nicaragua’s 1904 Civil Code, as amended, provides that no one may be deprived of property except by law or a decision grounded in law. In case of war, expropriation may precede indemnification. Public utility is not defined in the Constitution or the Civil Code. The extent of the GON’s use of its power of expropriation in recent years is not reported (Blandino 2007; IACHR 1994; Reynolds and Flores 2009).

In the 1980s, the Sandinista government expropriated about 40% of rural land for redistribution to poor peasants and the establishment of cooperatives, state farms. The GON continues to process claims for restitution and compensation for private land that was expropriated. Some claims have been granted but the GON has also denied many claims through retroactive application of Decrees No. 3 (1979) and No. 38 (1979), which legalized the confiscation of property belonging to the Somoza family and their close allies (USDOS 2010a).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Approximately 35% to 40% of all land in Nicaragua is subject to competing claims, primarily arising from two conflicting ownership claims, a result of land reforms and inadequate documentation. In the Atlantic region, most disputes are based on based on assertions of indigenous land rights. Land disputes have also been caused by natural disasters, such as hurricanes and flooding, which destroy land and other natural resources and put pressure on remaining resources. Local land conflicts are often based on competing ideologies: economic development vs. conservation; livelihoods vs. conservation; and peasant livelihoods vs. indigenous territorial rights. Conflicts may relate to inheritance or marital property disputes, competing claims of access to forest-based natural resources between indigenous communities within a defined area (as in the case Bosawás rainforest reserve between Mestizos and Mayangna Indian people), or between residents and forest and mining interests within a community (Broegaard 2009; Deininger et al. 2003; World Bank 2010a; UN-Habitat 2005b; USDOS 2011).

Nicaragua’s formal judicial system is widely perceived as inefficient, politicized, and corrupt. The average time for a local court to issue a preliminary ruling on a contract dispute is 540 days. Once judgments are rendered, their enforcement is not assured. The World Bank’s Governance Matters study ranked Nicaragua in the 22nd percentile for rule of law in 2008 while the World Economic Forum’s Competitive Index Rankings ranked Nicaragua 124th of 133 countries for judicial independence in 2009–2010. Land disputes may be pending in civil courts for 10 years or more. Most people avoid the courts and attempt to resolve difference through negotiation and mediation, often using village councils and local leaders to mediate disputes. International NGOs have asserted the rights of indigenous peoples in international tribunals (USDOS 2010a; University of Arizona 2009; COHRE 2003; Broegaard 2009; Broegaard 2005).

The GON created specialized bodies to address the many land-related conflicts that have resulted from the various land reforms, and these have performed with varying success. The National Confiscation Review Commission (CNRC) is the primary institution that considers confiscation claims. As of 2002, the CNRC had ordered indemnification to 74% of claimants, denied 13% of claims, and ordered the property returned to 5.8% of claimants. The State Attorney’s Office for Property prosecutes holders of land who were not the intended beneficiaries of reforms but who took advantage of the process to enrich themselves. In the course of such prosecutions, the GON acquires the properties, creating potential for abuse and corruption. As of 2002, little progress had been made on reclaiming such land, in part because the cases were bogged down within the judicial system. In 2003, the Supreme Court renamed these tribunals the National Property Court (COHRE 2003; UN-Habitat 2005b).

At the international level, Nicaragua and Honduras have a long history of territorial disputes, dating back to a dispute over a coastal area beginning in 1906. Currently the two countries have competing claims over several Caribbean islands that are rich in natural resources such as fish and oil. In 2007, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled that the islands Bobel Cay, South Cay, Savanna Cay, and Port Royal Cay, together with all other islands, cays, rocks, banks, and reefs claimed by Nicaragua that lie north of the 15th parallel, are under the sovereignty of the Republic of Honduras (ICJ 2007; Klerlein 2006).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

Since 2007, the Ortega administration has retained the legal and regulatory frameworks supporting a market economy and promoting macroeconomic stability. The GON has also worked to recognize the land rights of indigenous groups. As of 2009 over 123 indigenous communities live within territories registered in the name of their communities. These areas represent 8% of national territory. However, despite gains made, the continuing tenure insecurity caused by unresolved land claims and inadequate documentation of property rights continue to impede economic growth and investment in the agricultural sector (World Bank 2009b; Broegaard 2009).

The Productive Rural Development Programme (PRORURAL) was established in 2005 as a mechanism for coordinating and integrating the activities of the various GON agencies involved in agriculture and rural development and enlisting and harmonizing international support for these sectors. PRORURAL seeks to reduce rural poverty by increased competitiveness and environmental sustainability, greater participation in domestic and external markets, higher incomes and better income distribution, and creation of rural employment. PRORURAL works in seven areas: sustainable development of forestry and agro-forestry sector; raising the physical and financial capital of households and rural businesses; accelerating technical innovation through research, technical assistance, and education; complying with international standards related to food safety and standards; expanding and rehabilitating basic infrastructure; modernization and institutional strengthening of the public agencies concerned with agriculture and rural development; and formulation and implementation of policy and strategy for the sustainable rural development, and co-ordination of the implementation of the strategies and operating plans of the agencies within the agricultural public sector (USG 2010).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) pledged US $26 million to strengthen property rights in León, the second largest city in the country. The objectives of the Property Regularization Project were to strengthen property rights by: (1) increasing private returns to investments on land; (2) improving the ability to use land to access credit; (3) reducing high land transaction costs; and (4) reducing the need for expenditures to protect property rights. After issuing 2,865 titles and certificates, the MCC suspended the project because political conditions leading up to, during, and following the November 2008 elections were inconsistent with MCC’s eligibility criteria. In June 2009, MCC terminated a portion of their compact with Nicaragua, including the portion that had funded the Property Regularization Project. Thereafter, MCC worked with the World Bank to loan the GON US $10 million to continue the project (MCC 2009; MCC 2010).

The objectives of the World Bank Land Administration Project (2002–2013) are to: (1) develop the legal, institutional, technical, and participatory framework for the administration of property rights; and (2) to demonstrate the feasibility of a systematic land rights regularization program. An additional financing credit of US $10 million equivalent was approved on February 16, 2010 to support the scaling-up of most of the project’s activities in new municipalities in the departments of Madriz and Leon. The World Bank reports significant progress toward achieving the project development objectives is substantial. As of mid-2010, the overall framework for land administration has been strengthened and inter-institutional coordination improved. A systematic land rights regularization program has been developed and tested in the original project area. Cadastral activities have been completed in Chinandega and Esteli and 70% of Madriz, benefitting over 150,000 families, most of which are poor. Targets have been exceeded regarding demarcation of protected areas, with 12 areas demarcated and 10 management plans prepared under the Project. Finally, 12 indigenous peoples’ territories have been demarcated and titled in the Atlantic region. The additional funding obtained in 2010 will broaden the geographic scope of the project and support conflict mediation, a social and environmental communication campaign, and the development and implementation of an Integrated Property Information System to help track the issuance of land titles (World Bank 2010a; World Bank 2010b; USAID 2009).

USAID’s support in Nicaragua has been focused on improving access to justice and supporting small and medium-scale farmers. Since 2005, USAID has provided US $23.2 million in technical assistance and training to GON institutions working on legal reforms that increase access to justice, support the rule of law, and protect human rights, including establishing 12 mediation centers and two commercial arbitration and mediation centers where 2,000 cases have been mediated and resolved. From 2003 to 2009, USAID provided agriculture assistance to nearly 30,000 small- and medium-scale farmers to help them take advantage of the Central America-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR). Producers assisted by the ACORDAR program have had US $48.5 million in sales (29% from exports) of agricultural commodities and an estimated 11,240 new jobs have been generated since the program began in 2007 (USAID n.d.; USG 2010; USAID 2011).

Nicaragua is one of the countries targeted in the USG’s a Feed the Future initiative, and a Global Hunger and Food Security Initiative (GHFSI) Implementation Plan has been developed. USAID will lead the initiative to promote access to sufficient, safe, nutritious food in Nicaragua, and has begun with identification of priority investments to improve the country’s food security situation and creation of a policy agenda that will guide dialogue with the GON, civil society, and other donors in matters related to food security (USG 2010).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE, AND DISTRIBUTION

Nicaragua has extensive and diverse water resources but they are unevenly distributed across the country’s territory, population, and seasons. National water resources include 21 river basins, of which 13 drain to the Pacific Ocean, and eight to the Atlantic Ocean. The country has numerous rivers, streams and lakes, including the two largest freshwater lakes in Central America – Lake Nicaragua (8,264 square kilometers) and Lake Managua (644 square kilometers), both of which are in the Pacific region. The lakes provide the densely populated region with the only significant perennial surface water resources; annual rainfall ranges from 1,250–2,500 millimeters along the Pacific coast and 1,500 millimeters inland. Most rivers and streams in the Pacific region are seasonal, and drought is relatively common. In contrast, the thinly populated Atlantic region has an abundance of perennial rivers, streams, and lakes and averages 2,000–3,000 millimeters of annual rainwater in RAAN and 3,000–6,000 millimeters in RAAS. The country has a high incidence of earthquakes and volcanic activity, and hurricanes and flooding are common and cause substantial damage to the Caribbean coastline (USACE 2001; FAO 2000; INAA 2010).

Fresh groundwater is generally available throughout the country although often at depths greater than 90 meters, requiring motorized pumps for extraction. Groundwater supplies most of the country’s drinking water, while agriculture and industry rely primarily on surface water sources. Overall, agriculture accounts for most water use (83% of withdrawals), followed by domestic use (15%) and industry (2%). The principal irrigated crops include cereals, mostly maize, vegetables, and sugar cane. Water is also used in the wet processing of coffee, which is one of the country’s major export crops (World Bank 2009a; USACE 2001).

Nicaragua’s surface water suffers from extensive pollution and almost all rivers and lakes are contaminated. Untreated domestic and industrial waste – including pesticides, animal waste, and large amounts of soil – are routinely discharged into water sources. Gold mining and ore-refining activities also contribute to the chemical pollution of water sources. The country’s groundwater is generally of higher quality than surface water, but shallow aquifers in populated and industrial areas are increasingly contaminated and saltwater incursion is common along both coasts (European Commission (EC) 2007; USACE 2001).

In 2004, approximately 90% of the urban population and 63% of the rural population had access to national water supply services (piped and non-piped). In urban areas, illegal connections are common: as many as 200,000 of the connections supplying 40% of the water service in Managua are illegal. Only 56% of the urban population and 34% of the rural population had access to sewage services in 2004. In the poorest and least populated regions of RAAN and RAAS, an estimated 20% of the population receives water services and 30% receives sanitation services (WRI 2003; USACE 2001; World Bank 2008a).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution of Nicaragua provides that the state is responsible for the management of the country’s natural resources. The Constitution also recognizes and guarantees rights of Atlantic region communities (RAAN and RAAS) to the use of water on their communal lands (Larson 2008).

Nicaragua’s 2001 Water Policy establishes a number of guiding principles that were subsequently reflected in the country’s General Water Law, which was adopted in 2007. The Water Policy characterizes water resources as within the public domain and prioritizes use of water for human consumption. The policy supports the development of a water rights system, adopts polluter-pay and user-pay principles, and supports preservation of water quality and prevention of pollution (Novo and Garrido 2010; GON Water Law 2007a).

The 2007 General National Water Law (Ley General de Aguas Nacionales) (Water Law) governs the management and allocation of water resources in Nicaragua. The Water Law provides that water is in the public domain and incorporates the principles of integrated river basin management and decentralized management of water resources. The 2007 Water Law is consistent with Law No. 40 and Law No. 28, which give municipal and regional authorities authority over water resources within their borders (GON Water Law 2007a; Novo and Garrido 2010).

The 2007 Water Law provides a framework for the institutional structure for water management, regulates the issuance of permits, defines the rights and obligations of water service users, prohibits privatization of water as a resource or for drinking water services, and provides for the provision of water to the poor at affordable prices. The law calls for the creation of a National Water Authority (ANA), a decentralized body with administrative and financial autonomy. The ANA is responsible for drawing up a national water resources plan, keeping track of water levels in basins, maintaining a public registry of water rights, and promoting the use and development of water resources. The ANA is also expected to monitor the construction of water infrastructure. As of 2010, the ANA was not yet functioning and the Water Law had not been implemented. Observers have attributed the delay in implementation to competing claims to water resources, a struggle among various government bodies for authority over water resources, high levels of government turnover, and lack of funding (EC 2007; IELRC 2009; World Bank 2008a; WASH News 2010; Novo and Garrido 2010).

The Law-Decree No. 276 of 1998 created the Nicaraguan Water and Sewerage Enterprise (ENACAL); and Law No. 275 of 1998 transformed the Nicaraguan Institute for Water and Sanitation (INAA) into a regulatory agency (INAA 2010).

TENURE ISSUES

Under the 2007 Water Law, people have the right to water for domestic purposes. The state grants concessions, licenses, and authorizations for other water uses. The ANA is responsible for granting concessions and licenses for large projects, including drinking water systems, large-scale irrigation and hydropower. Municipal authorities are responsible for granting authorizations to use water for irrigation of three hectares or less and other minor uses. Water rights are generally available for periods of 5–30 years, and the law provides some guidelines for the award of rights. For example, landowners seeking authorization to use water sources on their land for irrigation shall receive priority for such use, followed by prior users of the water resources and those making first application. As of 2010, the ANA and most local governments had not yet begun issuing water rights under the Water Law, and water for irrigation was generally considered an open access resource (GON Water Law 2007; Novo and Garrido 2010).

The main method for accessing potable water in rural areas is through wells. The government, through the rural section of the Nicaraguan Water and Sewerage Enterprise, ENACAL-DAR, constructs wells. The local communities are responsible for maintenance, operation and treatment of the wells. Local Water and Sanitation Committees (CAPS), composed of local community members, undertake management of drinking water and sanitation services and maintenance of infrastructure in many rural areas. Donors provide about 60% of the funding to help provide wells and maintain the water delivery systems, with the GON funding the balance. In sparsely populated rural areas, water service is expensive and GON support is quite limited. In those remote areas and in RAAN and RAAS, which ENACAL-DAR does not serve, donors have taken on a larger share of the financial and technical support (USACE 2001; World Bank 2008a; World Bank 2008b).

Water-related conflicts are relatively common local and international levels and are expected to increase because of the impacts of climate change in the region and implementation of the 2007 Water Law, which creates a new institutional framework governing water resources. Most water conflicts occur at the local levels, such as conflicts between upstream and downstream users, between small and large farmers, and between competing uses. Under the Water Law, the ANA provides conflict mediation functions to the ANA. However, the law’s potential to reduce conflict has yet to be realized in practice because implementation of the law has been delayed. Major factors contributing to delay include budget constraints, lack of knowledge of the Water Law among stakeholders, lack of political will, entrenched interests, and lack of human capital due to high turnover of GON and local officials (Novo and Garrido 2010).

At the international level, Nicaragua has a 200-year-old dispute with neighboring Costa Rica over the management and use of the San Juan River, which forms much of the border between the two countries. In 2009, the United Nations International Court of Justice unanimously reaffirmed Nicaragua’s sovereignty over the river and upheld a ban on Costa Rican police forces using the river. Costa Rica may use the river for transport but has no right to withdraw the water (ASCA 2009; van Huijgevoort 2009).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

No single agency holds responsibility for overseeing all water-related issues, and all agencies and organizations that deal with water focus only on a specific aspect of the sector, with only limited coordination among organizations. The 2007 Water Law provides for decentralized model for water management with the ANA as the overarching agency in charge of regulating, administrating, monitoring and controlling water resources. River basin authorities will be set up under the ANA. However, the delay in implementation of the Water Law has also delayed establishment of ANA and most of the basin authorities; in the interim, at least 10 different governmental bodies have some authority over water resources (Novo and Garrido 2010; FSD 2007).

Four agencies share most of the responsibility for the sector: (1) the National Commission on Water and Sanitation (CONAPAS), the governing entity responsible for strategic planning regarding water; (2) the Nicaraguan Institute for Water and Sanitation (INAA), responsible for regulating tariffs, promoting efficient and adequate service quality and preventing formation of monopolies; (3) the Nicaraguan Water and Sewerage Enterprise (ENACAL and ENACAL-DAR), responsible for managing water supply and sanitation services in urban areas, monitoring and controlling water supply in rural areas, and establishing water well protection; and (4) the Social Emergency Investment Fund (FISE), responsible for oversight of rural water projects. Several other institutions have water-related responsibilities, including INETER, which is responsible for flood control and collection of water data; the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARENA), which is charged with protecting ground water and monitoring water quality; and the Ministry of Development, Industry, and Trade (MIFIC), which oversees the allocation of water resources and issuance of permits (USACE 2001; World Bank 2008a; ENACAL 2007).

In rural areas, Community Water and Sanitation Committees (CAPS) are responsible for the operation and maintenance of rural drinking water supply and sanitation services. CAPs do not appear to exercise any authority over or responsibility for water for irrigation, which is largely governed by farmers unions, local governments, and basin authorities. The 2007 Water Law gives ENACAL-DAR responsibility for the rural water sector, including management and oversight of the CAPs; the source of financial support for the services is not identified. CAPs and the development, operation, and maintenance of rural water infrastructure and service have been largely supported and funded by international organizations, aid agencies, and NGOs (World Bank 2008a; Novo and Garrido 2010).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The goals of the GON’s 2009–2011 National Human Development Plan (NHDP) for the water sector are to: (1) strengthen the administration, regulation, and organization of the sector; (2) mobilize donor resources in an organized and systematic manner; (3) promote proper management of water resources; (4) provide adequate maintenance to the systems, equipment, and infrastructure; (5) encourage and promote citizen, entrepreneurial and social responsibility towards the sector; and (6) promote the development and monitoring of water quality and stimulate the social, environmental, and financial sustainability of the strategy. In rural areas, the NHDP includes an investment program intended to restore and expand water infrastructure, including installation of alternative systems such as mini-aqueducts, and a program to include citizens in decision-making and implementation of water systems and operations. In urban areas, the GON plans to rehabilitate damaged infrastructure, promote citizen responsibility for maintenance of water infrastructure, and implement a plan to reduce water pollution. As of 2009, the GON reported drilling and rehabilitating 143 wells; connecting 69,042 homes to the drinking water pipeline system; and installing 73 km of drinking water piping (World Bank 2010c).

The GON adopted an energy plan, the 2010–2017 Generation Expansion Plan, which includes plans to increase installed hydroelectric capacity by 73% by 2017. Under the plan, Nicaragua will export energy to the rest of Central America through the Electric Interconnection System for Central American Countries (SIEPAC), an ongoing project with an investment of US $400 million (EUR €300 million). The Central American Bank for Economic Integration will provide US $120 million in the next five years (2007–2012) to finance hydroelectric projects (Business News Americas 2010; ProNicaragua 2009).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

International donors and agencies fund an estimated 60% of the GON’s investment in and operation of the water sector. International donors, the government, and civil society are represented on the Water and Sanitation Board, an entity created to coordinate the financial support and investments in the water sector. Donor interventions and investments are typically focused on: (1) improving access to safe and consistent water and sanitation services through national planning and infrastructure; and (2) improving the GON’s technical capacity to sustainably use and protect water resources (Novo and Garrido 2010).