Overview

OVERVIEW

Niger is among the poorest countries in the world, with most of its population dependent for their livelihoods upon subsistence agriculture and livestock-rearing. The country has experienced declining average rainfall, desertification, recurring droughts and deforestation. Undernourishment is widespread and the majority of the rural population does not have access to safe drinking water. The severe drought and food emergency in 2005 caused the under- or malnourishment of many and left the country’s population extremely vulnerable.

The government has been unsuccessful in its attempts through legislation to increase land tenure security for the population, individualize land-use rights, and reduce the power of traditional chiefs. Instead, there are now layers of often contradictory land rights. The 1993 Rural Code decentralizes land administration and allows for registration of customary land rights, but confusion over what rights can be registered, and the lack of capacity to manage land registration, has caused an increase in land disputes and increased the risk that those with less power to assert claims, such as women and pastoralists, will ultimately lose land rights.

In principle and under law, women and men have equal rights to land and other natural resources. However, in practice, rural women are among the country’s poorest people and their ability to access land depends on their relationships to male family members.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

Donors could consider the following land and natural resource interventions as ways to promote food security, improve natural resource management and increase economic growth through greater tenure security:

Many commentators have noted that the Rural Code is being only marginally implemented, and that where it is implemented it has uncovered latent conflicts without providing for an accessible and effective dispute-resolution forum, thus reducing tenure security. Donors could assist in reviewing the current status of the Rural Code’s implementation and provide technical advice for improving implementation or making necessary course-corrections. USAID in particular could use its expertise to evaluate the vision of the Rural Code against the situation on the ground and its impact to date, targeting the locations where pilot registration has occurred and pilot local land commissions have been established. The study could also investigate how the code’s implementation is affecting the country’s poorest families, emphasizing its impact on women.

Donors could support an evaluation of the Water Code in light of the Rural Code and customary practices. The study could include recommended changes to the Water Code that harmonize it with the Rural Code and customary practices on the ground. USAID in particular could work with the government to design pilot efforts to protect the rights of traditional user-groups to manage grazing resources and exclude others as necessary to promote sustainability.

One gap in the current framework for dispute resolution is the lack of implementing regulations for the Rural Code that could provide guidance to dispute-resolution tribunals. Donors could work with the government to draft such regulations. In addition, it might be appropriate to help the government amend the Rural Code to recognize and register overlapping tenure rights. Finally, donors could support an assessment of current conflict-resolution mechanisms and then assist the government in strengthening or creating local dispute- resolution institutions.

Summary

Following Niger’s President Tandja’s unconstitutional effort to extend his term in office, in 2009 most donors (including the US) suspended all but humanitarian assistance to the country. A military coup with substantial public support ousted President Tandja from office in February 2010. Political stability remains fragile in the months following the coup; the military junta is working toward creating a functioning government capable of responding to donor pressure for elections by the end of 2010. In the midst of the political upheaval, drought and failed harvests created a significant food security crisis in Niger. USAID has responded with US $48 million in humanitarian

Following Niger’s President Tandja’s unconstitutional effort to extend his term in office, in 2009 most donors (including the US) suspended all but humanitarian assistance to the country. A military coup with substantial public support ousted President Tandja from office in February 2010. Political stability remains fragile in the months following the coup; the military junta is working toward creating a functioning government capable of responding to donor pressure for elections by the end of 2010. In the midst of the political upheaval, drought and failed harvests created a significant food security crisis in Niger. USAID has responded with US $48 million in humanitarian

assistance (Reuters 2010; USAID 2010b).

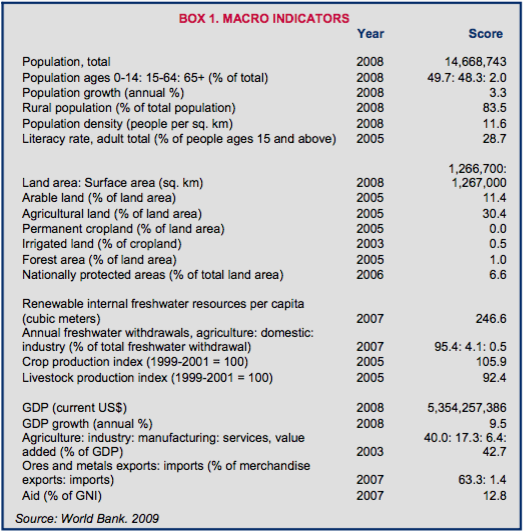

Niger is among the poorest countries in the world, ranking last in the most recent United Nations Human Development Index. Most Nigeriens depend on subsistence agriculture and livestock-rearing for their livelihoods – activities that are highly susceptible to the harsh climate, increasing degradation of soil and vegetation, and the droughts that plague the country. Thirty-two percent of the population is undernourished and 40% of children under five are chronically malnourished. Sixty-four percent of the rural population does not have access to safe drinking water, relying on pond water that is often contaminated with guinea worms, animal waste, and chemicals.

Since its independence from France in 1960, Niger’s successive governments have passed legislation intending to increase land tenure security for the population, support the individualization of land-use rights, and reduce the power of traditional chiefs. The laws have created layers of often contradictory land rights and have been largely unsuccessful at increasing land tenure security for the rural population. The Rural Code of 1993 allows for registration of customary land rights. The combination of confusion over what rights can be registered under the Rural Code and the lack of capacity in local institutions to manage land registration have caused an increase in land disputes and a risk that those with less power to assert claims, such as women and pastoralists, will ultimately lose land rights.

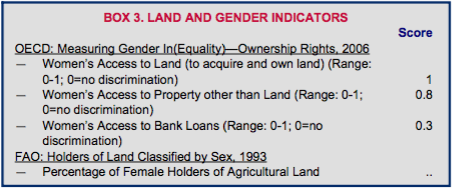

Niger’s Constitution asserts the right of all individuals to own property, and the Rural Code provides women and men with equal rights to land and other natural resources. Despite these formal pronouncements, Niger’s rural women are among the country’s poorest people; they have little economic power, are almost entirely dependent on the land for their livelihoods, and their ability to access land depends on their relationships to male family members. If those relationships end due to death, marriage, or divorce, women risk losing their means of survival.

Niger suffers from declining average rainfall, desertification, and drought. The country has limited forestland and deforestation is occurring at an annual rate of 1%, yet the vast majority of the population is dependent on forest resources for fuel. Policies in recent decades have encouraged the sustainable harvesting of fuelwood through regulated markets. Reforestation efforts to combat desertification are also underway.

Land Use

LAND USE

Niger has a total land mass of 1,266,700 square kilometers. In 2007, eighty-four percent of Niger’s 14 million people lived in rural areas, the vast majority in a semi-fertile swath of land along the country’s southern border where rainfed agriculture is possible. The northern half of the country is covered by the Sahara Desert and is sparsely populated. A semi-arid zone used for pastoralism separates the two areas (Hobbs 1998; Gnoumou and Bloch 2003; World Bank 2009a).

Niger’s 2008 total GDP was US $5.4 billion. No data is available for the breakdown of the 2008 GDP; however, in 2003, 40% of GDP came from agriculture, 17% from industry (6% of which was manufacturing), and 43% from services. Of the agricultural portion of GDP, 35% is attributed to livestock production; 12% of the overall GDP is due to livestock production. The livestock sector employs over one million people on a full-time basis. Permanent pastures cover roughly 60 million hectares. Pastoral management is directly linked to water management. Important corridors for livestock movements exist between Niger and Nigeria and between Niger and Benin (World Bank 2009a; Geesing and Djibo 2001; Gnoumou and Bloch 2003; AUC et al. 2008).

In 2003–2005, agricultural land comprised 30% of Niger’s total land area. Only 0.5% of Niger’s cropland was irrigated. Forests and woodlands make up 1% of the country, and nationally protected areas make up 7% of Niger’s total land area. Deforestation is occurring at an annual rate of 1% (Geesing and Djibo 2001; World Bank 2009a).

Most Nigeriens depend on subsistence agriculture and livestock-rearing for their livelihoods. Thirty-two percent of the population is undernourished and 40% of children under five are chronically malnourished. Niger ranks last in the most recent United Nations Human Development Index (UNDP 2009; UNICEF 2009).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Most of Niger’s population lives in the narrow swath of semi-fertile land along Niger’s southern border with Nigeria, Benin, and Burkina Faso. The major ethnic groups include Hausa (53%), Dierma (21%), Tuareg (11%), Fulani (7%), and Beri Beri (6%). Both the Hausa and Dierma are sedentary farmers who live in the southern portion of the country. The other ethnic groups are nomadic or semi-nomadic pastoralists. Northern areas are sparsely populated by both nomadic and settled Tuareg and Fulani peoples (Geesing and Djibo 2001; Hobbs 1998; USDOS 2009).

Rural land includes individual land, family land, and village common lands, known as chieftaincy lands. The chieftaincy lands include cultivated land, pasture land, fallow, and land devoted to village activities; chieftaincy lands are held and managed by the chief on behalf of the group. Rural farming families have landholdings averaging five acres of dry land. Some families also have access to small plots (less than one hectare) of irrigated land. The deteriorating quality of the soil has caused farmers to expand the area of land cultivated, often encroaching on land used by pastoralists for grazing and creating the potential for conflict (FAO 2007; Gnoumou and Bloch 2003).

At Independence in 1960, a survey concluded that land ownership was highly concentrated in the hands of traditional leaders, and recommended that the government engage in land reforms to gain popular support, improve the productivity of the land, and conserve natural resources. Successive governments have enacted land reform legislation, including laws granting land to the tiller, reducing the power of traditional chiefs, and individualizing chieftaincy land. The laws have been imperfectly implemented and have failed to account for the political power of traditional leaders and the wide range of land- and natural resource interests, resulting in confusion of land tenure and a high incidence of land conflict (Gnoumou and Bloch 2003).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Niger’s Rural Code (Principes d’Orientation du Code Rural, Ordinance 93-015 of 2 March 1993) is the most recent land legislation in Niger. The Rural Code has the following objectives: (1) increase rural tenure security; (2) better organize and manage rural land; (3) promote sustainable natural resource management and conservation; and (4) better plan and manage the country’s natural resources. The code seeks to strengthen tenure security by recognizing the private property rights of groups and individuals if such rights were acquired according to either customary or formal law. The Rural Code has not been effectively implemented in much of the country (Gnoumou and Bloch 2003; CILSS 2003; RON 1993).

Customary land tenure practices govern all types of land, including agricultural land, pasture land, and housing plots. The laws have significant regional variations in subjects such as the right to inherit land, individual and family tenure, and women’s land access. Most customary practices reflect the influence of Shari’a law (Hobbs 1998).

TENURE TYPES

Rural lands are managed by customary institutions that hold lands according to a variety of indigenous tenure forms. Many customary rights to land are recognized under the Rural Code and can be registered. Urban lands are owned and managed by the state and by collectives; occupants enjoy use-rights. Vacant lands are owned by the state (AUC et al. 2008).

Rural lands are managed by customary institutions that hold lands according to a variety of indigenous tenure forms. Many customary rights to land are recognized under the Rural Code and can be registered. Urban lands are owned and managed by the state and by collectives; occupants enjoy use-rights. Vacant lands are owned by the state (AUC et al. 2008).

Rural lands are managed by customary institutions that hold lands according to a variety of indigenous tenure forms. Many customary rights to land are recognized under the Rural Code and can be registered. Urban lands are owned and managed by the state and by collectives; occupants enjoy use-rights. Vacant lands are owned by the state (AUC et al. 2008).

Two types of land tenure are recognized in rural Niger: individualized ownership rights and a variety of land-use rights. Successive regimes beginning in 1960 imposed land reforms that granted ownership rights to holders of customary rights to rural land. Chiefs and those with economic and political power obtained ownership rights to land during these years, supported by formal or informal documentation. Landowners have the right to use the land as they wish, exclude others from the land, and lease or sell the land. Use rights can be held by families or individuals and range in the extent of authority over the land. In some cases, families hold individualized parcels over which they have complete control, but traditional leaders and principles of customary law discourage them from selling. In other cases, families and individuals borrow land from pooled community land managed by the village chief. The landholder cannot lease, lend, or sell the land and must return it to the pool if it is not used. The system also recognizes tenancy relationships in which landowners or the traditional authority controls the use and management of the land with the tenant providing labor (Gnoumou and Bloch 2003; McCarthy et al. 2004; Landtenure.info n.d.).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Customary law and traditional practice provide that rural land in Niger can be acquired under the principle of the right of first occupant. If a village is established in a previously unoccupied area, the village chief of the first occupants has the power to grant use-rights to newcomers. In present day, the main avenues for acquiring land rights in agricultural communities include: (1) inheritance; (2) borrowing fields in exchange for rent paid in the form of a symbolic payment of produce; (3) pledging, in which the user gives a cash loan in return for cultivation rights for the duration of the loan; and (4) land purchase, which is becoming more common in south-central Niger, where the most productive agricultural land is located. Land transactions take place on the informal market and are validated through witnesses or, in the case of land sales, often by written agreements (Hobbs 1998; McCarthy et al. 2004; Gnoumou and Bloch 2003; Ngaido 1996).

Among pastoralists, land-use rights are directly linked to water-use rights. Individuals and groups who control access to a water-point exercise de facto control over access to surrounding land (Cotula 2006).

Urban land rights are allocated by the government in the form of use rights, which the state regulates. Local land tenure commissions can temporarily take land from owners who use land irresponsibly or neglect or abuse the land (AUC et al. 2008; Hobbs 1998).

With adoption of the Rural Code, demand for tangible, written evidence of rights has increased. An agriculturalist has two options for obtaining written proof of the land right: (1) apply with the Land Register to receive a proper deed; or (2) apply for a certificat written and signed by the Chef de canton. Requests for deeds have overwhelmed the institutions charged with creating them, which already suffered from poorly educated staff and lack of capacity (Benjaminsen et al. 2008).

Land Commissions are charged with determining land ownership and recording land rights but are hampered by lack of training, capacity, and funding to execute their duties. In areas where Land Commissions are functional, they determine ownership rights through survey and oral testimony. If there are no objections, the rights are recorded in a rural land register and the landowner is given a property-ownership registration certificate that varies depending on whether the land was acquired by inheritance, gift, purchase, or allocation. The Land Commissions have no authority to adjudicate land disputes and competing land interests, and can only register undisputed claims. As of 2004, a total of only 3100 registrations had been processed (Gnoumou and Bloch 2003; FAO-Dimitra 2008).

The Rural Code allows for formal registration of some categories of customary rights to land. The law does not account for the historical patterns of landholdings, and layers of rights and disputes have arisen as various interests seek to register rights to the same land. Simplification of a complex composite tenure system created categories of primary right holders and weaker groups of secondary right holders. Those who lose rights tend to be women, pastoralists, and other less powerful groups (Benjaminsen et al. 2008; Ngaido 1996).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Women are among the poorest and most vulnerable groups in Niger. Although almost all of Niger’s women work in agriculture, women possess little economic power, and access land only through male relatives. The Rural Code calls for both men and women to have equal access to land and natural resources. The law provides that women can own, buy and sell land. Under customary law, however, women do not own land; their husbands and male relatives own the agricultural land that they cultivate and the small plot near the house that they may use for a kitchen garden. In some instances, organized groups of women are able to access pieces of land during the second cropping season. Because women access land through their husbands and male relatives, they risk losing the land when those relationships end due to death, marriage, and divorce (Landtenure.info n.d.; FAO-Dimitra 2008).

Women are among the poorest and most vulnerable groups in Niger. Although almost all of Niger’s women work in agriculture, women possess little economic power, and access land only through male relatives. The Rural Code calls for both men and women to have equal access to land and natural resources. The law provides that women can own, buy and sell land. Under customary law, however, women do not own land; their husbands and male relatives own the agricultural land that they cultivate and the small plot near the house that they may use for a kitchen garden. In some instances, organized groups of women are able to access pieces of land during the second cropping season. Because women access land through their husbands and male relatives, they risk losing the land when those relationships end due to death, marriage, and divorce (Landtenure.info n.d.; FAO-Dimitra 2008).

In some traditional groups, notably the Hausa, women cultivate their own fields and commonly inherit land. Most of Niger’s population is Muslim, and Islamic Law accords women the right to inherit property (in shares half the size of male relatives), but this practice is rarely followed among Muslims in rural Niger. In urban areas, Muslim women are more likely to inherit property, but the right rarely includes land (FAO-Dimitra 2008).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The National Committee on the Rural Code is the central decision-making body responsible for the implementation of the Rural Code. The Permanent Secretariat of the Rural Code is responsible for developing policies and laws that complement and support the Rural Code, create a resource center, and evaluate the work of the decentralized land commissions (Gnoumou and Bloch 2003).

The Rural Code establishes Land Commissions at three levels: department, commune, and village. Land Commission members include technical government departments at the local level, municipal departments, customary authorities, and civil society. Women are represented at every Land Commission level (AUC et al. 2008; Diarra and Monimart 2006).

Land Commissions implement the Rural Code at the local level and are given responsibility to verify and confirm land rights and to record land and ownership rights. They are also responsible for educating the local public about the Rural Code. Local Land Commission membership includes the technical government land administrative departments at the local level, representatives of the municipal departments, customary leaders, and local civil society representatives. While Land Commissions have been established in all areas, many are not functioning (Gnoumou and Bloch 2003; AUC et al. 2008).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Agricultural land is held communally in many areas of the country, and even where communal land is individualized and passed from generation to generation, customary law often precludes sale of the land. In the relatively prosperous agricultural zone of south-central Niger, political and economic elites obtained individualized ownership rights to land in the period following Independence, and an informal land sales market has developed (Hobbs 1998; Gnoumou and Bloch 2003; McCarthy et al. 2004; Land tenure.info n.d.).

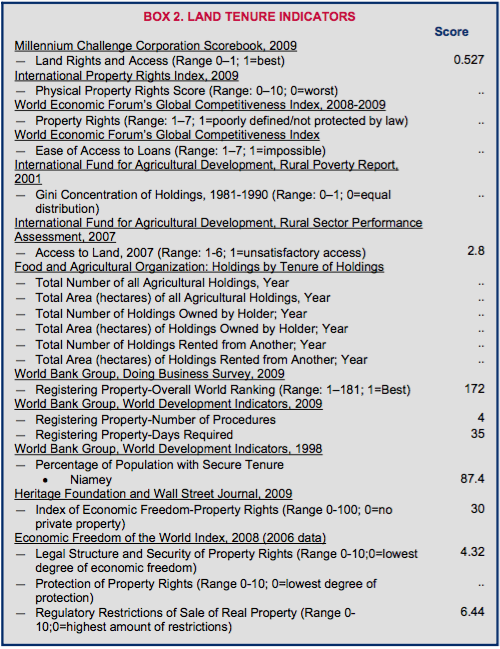

Registering a formal property transaction in Niger requires four procedures, costs 11% of the property’s value, and takes an average of 35 days. Steps include: (1) checking the ownership of the property at the Land Registry; (2) requesting a notary to draft the sales deed; (3) registering the new ownership with the Tax Authorities; and (4) transferring the property title within the Land Registry. This process is faster and more streamlined than the sub-Saharan average, but costs slightly more than the sub-Saharan average of 9% of property value (World Bank 2008a).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Article 21 of the Constitution provides that no one can be deprived of property except when taken for public use and when the landholder is fairly compensated in advance. The Rural Code narrowed the state’s ability to expropriate land for public use. Previous legislation had declared all unregistered land as property of the state and stated that such land could be appropriated at will with no compensation. The Rural Code strengthens individual and community property rights and requires the state to pay just compensation for land expropriated for a public use (Hobbs 1998; RON 1999).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

The growing population, soil degradation, and competing land uses have increased the pressure on Niger’s agricultural and pasture land. Three types of land conflict are common: (1) intra-family conflicts; (2) conflicts between pastoralists and sedentary farmers; and (3) conflicts between villagers and traditional chiefs over access to and use of land (Gnoumou and Bloch 2003).

The enactment of the Rural Code in 1993 caused an increase in the number of land disputes. The Rural Code permits the registration of customary rights but is ambiguous about which rights can be registered and the priority for registration. The Rural Code repeals prior inconsistent legislation, but authorizes formalization of land rights based on land rights created by (or at least consistent with) prior legislation. To some extent, therefore, prior land policies continue to define land rights. The Land Commissions established to manage the identification of land rights and registration of land do not have authority or capacity to hear and address land disputes, yet require all competing claims to land to be resolved before land is registered. These circumstances increase the insecurity of land tenure and the number of land disputes (Gnoumou and Bloch 2003; RON 1993).

Multiple institutions are involved in dispute resolution, including local administrative institutions, the formal court system, and traditional institutions (including village and canton chiefs). Landholders most often approach traditional institutions before turning to administrative forums or the formal court system. Where the Land Commissions are not functioning or are not able to register land, landholders may also seek to formalize their land rights through the traditional authority, circumventing the requirements of formal law altogether (Gnoumou and Bloch 2003; AUC et al. 2008; Benjaminsen 2008).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

Niger’s 2003 Rural Development Strategy and 2006 Action Plan created a joint plan to promote improved use and production in the agricultural, livestock, forest and fisheries sectors. The policies seek to support the livestock and agricultural sectors by strengthening marketing channels, supporting infrastructure such as irrigation, strengthening management of natural resources, and fighting desertification (World Bank 2008b).

In the early 1990s, with financing from the European Union (EU), the Permanent Secretariat of the Rural Code undertook a pilot project to enforce land legislation and sustainable management of natural resources. The project required active participation of women as members of the Land Commissions, and is credited with the achievement of a high percentage of female participation in the governance of land matters through the Land Commissions and as land project participants (CILSS 2003).

With funding and technical support from the World Bank, the Government of Niger has implemented a US $40.3 million Community Action Program designed to improve rural communes’ capacity to design and implement, in a participatory manner, Communal Development Plans (CDP) and Annual Investment Plans (AIP), and ultimately to contribute to enhancing rural livelihoods. The five-year project (2008–2013) includes capacity-building and improving the legal and institutional frameworks for participatory local development by working with key national institutions responsible for promoting decentralization and local development. The project will also establish a Local Investment Fund (LIF), to stimulate local development and to empower communes and communities to provide a response to their priority needs (World Bank 2009b).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

USAID does not currently have a mission in Niger; support for Niger is managed through the West Africa regional office in Ghana. The West Africa Regional Program areas of focus are: (1) improving regional food security through better management of natural resources and agricultural growth; (2) promoting peace and stability; (3) improving health; and (4) fostering regional economic integration and trade. In response to the country’s food insecurity crisis, the US Government supplied stocks of food and humanitarian aid to the country (USAID 2005; USDOS 2008; USAID 2010; USAID 2010b).

USAID supported the process of drafting Niger’s 1993 Rural Code, and USAID is the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC)’s implementing partner in a three-year (2008–2011) US $23 million program that focuses on improving rights and access to land as one of several components. Program goals include: implementing administrative and legal reforms to reduce the time and costs associated with land ownership, transfer, land valuation, building permitting and notarization; conducting a study on the institutional framework required to implement necessary reforms, with the recommendations to be implemented during the Program’s second year; organizing a public-awareness campaign to publicize land reform activities; and conducting a study on how to integrate Land Commission titles into Niger’s land registry, with the recommendations to be implemented in the medium-term as part of Niger’s broader rural development strategy (Hobbs 1998; MCC 2008).

Oxfam’s Regional Pastoral Programme, which includes Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso, supports the emergence and strengthening of pastoral organizations, develops the capacity of pastoral organizations, supports initiatives to include pastoral organizations in national decision-making, supports improved access to services for pastoralists, and carries out research on the impact of climate change on pastoralists (Oxfam 2009).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Niger depends on sources outside its boundaries for 90% of its water resources. Niger is located in two major transborder basins: the Irhazer Lullemeden and Chad Basins. The Niger River crosses the southwest of Niger and is the only permanent river in the country. Important wetlands within Niger (and crossing into neighboring countries) include Lake Chad and the W National Park (named because the Niger River flowing through the park forms the letter “W”). W Park makes up 220,000 hectares and is registered under the Ramsar Convention on Internationally Protected Wetlands (Cotula 2006; FAO 2005).

Niger has 34 cubic kilometers per year of renewable water resources of which 31 cubic kilometers is surface water and the balance is groundwater. An estimated 20% of the country’s groundwater resources are currently being exploited. Sixty-four percent of the rural population does not have access to safe drinking water. Many are only able to access pond water, which is often contaminated with guinea worms, animal waste, and chemicals (UNDP 2009; UNICEF 2009; FAO 2005; IRIN 2006).

Ninety-five percent of total water-use is dedicated to agriculture. The majority of Nigeriens depend on subsistence farming for food and, historically, seasonal rainfall provided enough water for farming. However, regional rainfall has declined an estimated 20–50% over the course of the last 30 years, and recent droughts have resulted in severe food shortages. Desertification is a growing problem (FAO 2005; IRIN 2006).

In some years, Niger is severely impacted by drought in combination with locust invasions, which cause devastating food and pasture shortages (Cotula 2006).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Niger’s Water Code was passed in 1993 and amended in 1998. Under the Water Code, access to public water-points is open to all, including outsiders such as nomadic pastoralists. Public water-points are managed by local Management Committees. Construction of new water-points with a daily capacity above 40 cubic meters requires governmental authorization (Cotula 2006).

The 1993 Rural Code addresses both land and water issues, and in some areas conflicts with the Water Code. The Rural Code grants pastoralists a common right to rangelands, and priority rights over both land and water in their home areas (terroir d’attache). Outsiders must negotiate access to water and grazing rights in these areas. In contrast, the Water Code grants open access to public water-points (Cotula 2006).

TENURE ISSUES

Under the Water Code, users can create a water point to extract up to 40 cubic meters per day based on a user declaration; government authorization is necessary to create water extraction infrastructure above 40 cubic meters per day (Cotula 2006).

Under customary law, groups that create water points by digging wells have priority rights to the water. Groups may negotiate the terms of access for outsiders to use the water source such as length of stay, time of day for watering, and health of livestock. Payment for access can be made in cash or barter. Groups often demand reciprocal access to water rights controlled by the outsiders. These local agreements (conventions locales) help reduce conflicts over resources (Cotula 2006).

This traditional system has been disrupted by state-sponsored pastoral water rights programs. As the state started constructing cement-lined wells in the years following World War II, areas around these wells became open access. The rights of groups with traditional control over the lands surrounding those water points diminished. Large state wells also allow larger numbers of livestock to be watered, encouraging increases in herd size that the surrounding rangelands cannot sustainably support (Cotula 2006).

Private operators are increasingly creating and managing water points. The state grants long-term leases to private operators to build or upgrade irrigation infrastructure, and private wells with exclusive rights are becoming more common (Cotula 2006).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Water Resources, Environment and Desertification Control, the Ministry of Agricultural Development, the Ministry of Animal Resources, and the National Environmental Council for Sustainable Development all have responsibility for management of Niger’s water resources (CIA 2010; FAO 2005).

Water supply to urban areas is overseen by Société du patrimoine des eaux du Niger (SPEN) and the Corporation for the Exploitation of the Water of the Niger River (SEEN). The Office des Eaux et du Sous-Sol (OFEDES) builds and maintains wells. The Niger Association for the Development of Private Irrigation (ANPIP) promotes the sustainable development of small-scale irrigation (FAO 2005; Cotula 2006).

Public water-points are managed by management committees (comités de gestion). These are responsible for general maintenance and collection of user fees. The committees’ ability to control access is very limited (Cotula 2006).

Niger is part of the Niger River Basin Authority (NRBA) along with Guinea, Mali, Cote d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Benin, Chad and Nigeria. The country is also a member of the Lake Chad Basin Commission, which includes Cameroon, Chad, the Central African Republic and Nigeria (AUC et al. 2008).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Niger’s 2002 Poverty Reduction Development Strategy calls for the development of improved irrigation infrastructure as a priority area. There is concern that water infrastructure projects are being planned without a full understanding of their impact on land tenure issues (Cotula 2006).

In 2006 the Niger Basin Initiative (NBI) was launched bringing together the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the NRBA, Wetlands International, and the Nigerien Conservation Foundation (NCF). The goal of this initiative is to ensure that environmental concerns are addressed in water basin development (IRIN 2006).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The World Bank is working jointly with France, Germany, Denmark, the EU, the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) to support the implementation of the Niger’s Rural Development Strategy, with special focus on irrigation and sustainable land and water resources management. In 2008, the Bank concluded a six-year US $45 million Private Irrigation Promotion Project (PIP2), which followed a 1996–2001 pilot project. PIP2 was designed to advance the Government of Niger’s agricultural-sector growth objectives through: (1) intensification and diversification of irrigated production to improve food security; (2) private sector development and empowerment of farmer associations and other agricultural organizations; (3) availability of sustainable financial arrangements in rural areas; and (4) the creation of a production environment that is environmentally sustainable and socially equitable. The completion report concluded that cost-effective small-scale irrigation with full participation of the private sector was valid and highly relevant for Niger. Irrigation investments under the project had an average cost of approximately US $2000 per hectare. These investments can bring measurable improvements in farmers’ welfare and achieve high economic rates of return, possibly above 20 % (World Bank 2009c; World Bank 2008b).

The World Bank, with the AfDB, European Investment Bank (EIB) and West African Development Bank (WADB), plan support for urban water delivery. The World Bank’s Local Urban Infrastructure Development Project includes a component on urban water supply and sanitation (World Bank 2008b; AiDA 2009).

The World Bank’s Community Action Program finances the creation of local development plans generated by communities and local governments. The broad aim of the program is to support sustainable natural resource management and local capacity. The Bank is providing technical assistance to scale-up sustainable land and water management in Niger (World Bank 2008b).

The Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development (KFAED) funds several village and pastoral water-supply projects that improve or build wells and work on resource management (AiDA 2009).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Forests make up 1% of the country, and nationally protected areas make up 7% of Niger’s total land area. The densest forests are in the extreme south. Niger is working to promote sustainable management of its forest resources while still supplying rural and urban residents’ fuel needs through fee structures and organized fuelwood markets (World Bank 2009a; Cotula 2006; FAO 2005).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Niger adopted a Forest Code in 2004. The code governs forest resource management and exploitation. The law defines all non-agricultural vegetation as “forest,” a definition that encompasses grazing land. The code devolves forest management in some instances to the commune level (the local government administrative division) in accordance with the country’s decentralization plan (Vogt et al. 2007).

Niger’s Domestic Energy Strategy (SED) focuses on the value of standing trees, public-awareness building within local populations regarding the value of the forests, and local responsibility for the management of forest areas. The Strategy includes taxation on fuelwood. Legislation governing this fuelwood taxation system includes Order No. 92-037, Decree 92-279 of 21 August 1992 and Order 09/MHE/DE of 23 February 1993 (Hamissou 2001; FAO 2000).

TENURE ISSUES

Forest reserves are controlled by the state through its technical service. In the Takiéta Forest Reserve the state has introduced governance systems to give local people more say in the reserve’s management. Non-reserve areas, which include all non-agricultural areas under the law, are governed by the Forestry Code and managed by the Forest Department. Inclusion of local populations in decision making is mixed. Licenses are necessary to exploit wood from forest reserves and to sell it in approved fuelwood markets. The Forestry Code also provides that organized groups can gain rural concession rights to forest land controlled by local communes (Vogt et al. 2007).

Under Niger’s SED, a license and taxation system is put in place to promote the sustainable use of fuelwood resources. Rural fuelwood markets have been established in which wood is sold by a local body that is recognized by formal and customary institutions. Permits to sell fuelwood are linked to the creation of plans for the sustainable management of the resource. The creation of these markets is encouraged by the preferential tax rate on wood purchased through them. All wood-haulers are subject to tax with the exception of those transferring wood from a private registered forest, resident users of forests who are exercising traditional rights, and public organizations without a working budget (Delville 2000; Hamissou 2001).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Forest Department has responsibility for forested areas, including reserves and non-reserves (Vogt et al. 2007).

The 1993 Rural Code permits the devolution of the management and use of woodlands from the central government to communes, and in some cases to groups of local people through rural concessions (Delville 2000).

As of March 2010, the Ministry for Water Resources, Environment and Desertification Control has responsibility for desertification and environmental issues related to forests (CIA 2010; Hamissou 2001).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Recent reforms in the forestry sector include the 2004 Forestry Code and the Domestic Energy Strategy (SED) (FAO 2000).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Many NGOs are involved in forestry issues; the primary funders of these NGOs are bilateral donors from France, Canada, Switzerland, Belgium, Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands, as well as the EU, USAID, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the World Bank (Hamissou 2001).

The World Bank funds a small project (US $100,000) on Carbon Sequestration and Rural Livelihoods Improvements through Acacia Plantations. The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) funds several small projects on rural development that contain forestry components, such as work on forest management and policy related to desertification (AiDA 2009).

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Niger has significant industrial mining potential in uranium, gold, salt, calcium, phosphates, cassiterite, and gypsum. Niger’s mineral production also includes cement, coal, gypsum, limestone, salt, silver and tin. Artisanal mining creates employment opportunities for local populations, and reduces the need for migration for employment. Artisanal mining operations are also responsible for loss of forest land, occupation and destruction of farmland, and population pressure in areas where mining is established (IF 2008; Bermúdez-Lugo 2006).

Uranium provides just over half of the country’s export revenues; gold accounts for 14% of export revenues. In 2006, Niger was the world’s fourth-largest uranium producer. In 2008 the French firm AREVA was awarded a license to build Imouraren uranium mine in Niger; the mine is expected to be the biggest uranium mine in Africa. Oil is now also being produced in Niger for export. As of 2008, China planned to invest US $5 billion in the country’s oil export business, including building a 2000-kilometer pipeline (Bermúdez-Lugo 2006; AUC et al. 2008; USDOS 2009; BBC 2009a; BBC 2008).

The mineral sector accounts for roughly 4% of Niger’s GDP and 40% of exports. In 2004, uranium earnings accounted for 30% of the formal economy. The country’s Mining Code calls for 15% of mineral sector earnings to be allocated to local development projects (the other 85% goes to the national budget) (Bermúdez-Lugo 2006; OECD 2006; AUC et al. 2008).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

A new Mining Code (Law No. 2006-26 of 9 August 2006) was adopted in 2006; detailed implementing regulations have yet to be adopted (AUC et al. 2008; Bermúdez-Lugo 2006).

TENURE ISSUES

Under the Mining Code, rights to explore and exploit resources are granted by permit, concession, and lease. Four types of mining rights are available to companies and individuals interested in exploration and development of mineral resources, summarized as follows.

- A Prospecting Authorization gives the holder a non-exclusive right to search for one or more minerals.

- An Exploration Permit is valid for renewable periods of three years.

- A Mining Permit is available in the event of a successful exploration and subject to the right of the Government to participate in the project. A small mine permit is valid for five years; a large mine permit lasts for 20 years initially. Both periods are renewable. The Government requires an initial 10% share in the mining project, free of all costs, which can later be increased to a maximum of 30% through share purchases.

- An Authorization for Small-Scale Mining is available for artisanal mining (Bermúdez-Lugo 2006; IF 2008).

Since the passage of the new Mining Code, a large number of new mineral exploration permits have been issued. Conflict is developing in northern Niger between Tuareg nomads and the state over control of the uranium wealth located in the area. While valuable uranium is mined in their traditional range, almost none of the earnings are seen by local people, who lose access to grazing land as a result of mining operations. In 2009, rebel groups agreed to a ceasefire and began negotiations with the government (Polgreen 2008; AUC et al. 2008; BBC 2009b).

GOVERNMENT AND CUSTOMARY ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Mining and Energy governs the mining sector. The Mining Code replaced the National Mine Research Office with two new institutions: the Geological and Mining Research Center and the Société du Patrimoine des Mines du Niger (SOPAMIN) (CIA 2010; Bermúdez-Lugo 2006).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

With support from the EU, the Government of Niger instituted a EUR €35 million Program to Strengthen and Diversify the Mining Sector in Niger (Programme de Renforcement et de Diversification du Secteur Minier au Niger, PRDSM). The overall objective of the program is to ensure that the mining sector supports the economic and social development of the country, and fights poverty by helping to: (1) improve the performance of the uranium sector, thus increasing government revenues; (2) support the mining resources diversification policy; (3) support small-scale mining activities and artisanal miners by assisting the project unit of the Small-scale Miners and Mining Enterprises Project (Projet d’Assistance aux Petites Entreprises et Artisans Miniers, PAPEAM); and (4) provide institutional support aimed at modernizing the structures of the Ministry of Mines and improving the legislative and regulatory framework of the sector (IF 2008).

In 2007, Niger was accepted as a Candidate Country under the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), which supports governance in resource-rich countries by improving transparency and accountability in the extractives sector through verification and full publication of company payments and government revenues from oil, gas and mining. Niger received an extension until September 2010 for filing its EITI Validation (EITI 2010).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The NGO Greenpeace has been an active critic of the uranium mining industry in Niger, alleging that the mines are posing substantial health risks to miners and residents. In early 2010, Greenpeace visited the uranium mines in Arlit and Akokan. The mines are operated by subsidiaries of the French company, AREVA. Greenpeace allegedly found dangerous levels of radiation in the streets. AREVA has denied allegations and offered its own studies of radiation levels (Greenpeace 2009; AREVA 2010).