Overview

Tanzania’s property rights and resource governance systems have been in flux for more than 50 years. Just prior to independence in 1961, the British colonial government attempted to introduce the concept of freehold land ownership, but the proposal was rejected by TANU, the Tanzanian political party that took power when independence was granted. Instead, the new President of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere, developed and applied the concept of “African socialism,” an initiative that transferred the customary land rights of ethnic groups and clans to newly established elected village councils and encouraged collective cultivation of the land. While this approach was embraced by some, such as women, who found their access to and security in landholdings improved, the new system did not foster greater investment, sound resource management, or adequate rates of economic growth. The sometimes-forced movement of people into villages under the policy of ujamaa (collective production) resulted in better health and education services and the creation of a “Tanzanian” identity, but it did not lead to broad-based economic growth. The country remained among the poorest in the world.

When President Nyerere left power in 1985, the government of President Mwinyi began to chart new directions for Tanzania’s economy and society. By the early 1990s, it was apparent that a new approach to property rights and resource governance was needed, and steps were taken, including the establishment of a Presidential Commission of Inquiry regarding Land Matters (the Shivji Commission), to define it. The government prepared Tanzania’s first National Land Policy in 1995, which led to the enactment of the Village Land Act and the Land Act in 1999. The Policy argued that procedures for obtaining title to land should be simplified, that land administration should be transparent; further, it recognized that secure land tenure plays a large role in promoting peace and national unity.

The Acts provide the legal framework for land rights, recognize customary tenure, and empower local governments to manage Village Land. This framework creates two main processes for securing land rights: in rural areas, village lands may be demarcated and land use plans created to provide for Certificates of Village Land (CVL). Once a village has a CVL, people living within the village may apply for Certificates of Customary Rights of Occupancy (CCROs). While the process has been slow, approximately 10,000 CVLs have been issued though few rural residents hold CCROs. In urban areas, people may apply for Certificates of Rights of Occupancy (CROs). In order to acquire both CCROs and CROs, parcel holders must have the boundaries of their lands mapped and their rights recorded and registered. Non-Tanzanians may not own land but may apply for derivative rights to use land for periods of time, for example, to develop an irrigated rice plantation or to build a factory in an urban area. This legal framework also retained the rights that women were granted and continued some of the laws regarding communal management of rangeland, forests and wildlife, especially with the idea of preserving Tanzania’s great national wealth of wild animals.

The approach also involved a gradual transition to a legal framework that supports private property rights. At the same time, all land in Tanzania is considered public land, which is held by the President of Tanzania, in trust for the people. Individualized (rather than collective) control of resources in farming areas is permitted and private investments that utilize Tanzania’s natural resources for economic gain are promoted. In some cases, land holders and users have been vulnerable to expropriation by the government if it is deemed necessary for the public interest.

Despite the progressive provisions of customary land rights and decentralization under the Village Land Act of 1999, land law has not yet been effectively integrated into the land governance framework: village authorities often lack the financial and human resources to effectively perform their duties. Furthermore, given the current global demand for land, the ease by which the executive branch can appropriate Village Land is also a concern, particularly since Tanzania is rich in natural resources, including abundant agricultural land, forests, water, and minerals. Overlapping roles of the Ministry of Land and the Prime Minister’s Office, Regional Administration and Local Government (PMO-RALG), and weak governance in land administration pose major concerns in terms of delivering land rights in an efficient and equitable manner.

The Strategic Plan for the Implementation of the Land Laws (SPILL), prepared in 2005 and revised in 2013, seeks to ensure that land law and governance better supports the current and future social, economic, and environmental development of the country. This will be crucial to the success of Tanzania’s ambitious Five Year Development Plan 2011-2016, which focuses on priority areas, including urban development, infrastructure, Information and Communication Technology, agriculture investments, mining, livestock and fishing, forestry and wildlife, and land and housing at the regional level. As part of the Tanzania Government’s effort to transition the country from low to middle-income economy, a program called Big Results Now, is working to accelerate achievement of middle income status by 2025 and transition out of aid dependency by identifying and resolving constraints to results delivery in the Government’s priority areas (initially: energy, water, transport, agriculture, education and resource mobilization, with more to be added in future years). The results-driven monitoring system will enable high-level oversight of progress, make the existing system work, and emphasize transparency and accountability for performance. In the agricultural sector the initiative seeks to support small holder farming covering 330,000 hectares of land by issuing Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy (CCROs) to 52,500 smallholder farmers in rice irrigation and marketing schemes as well as constructing irrigation infrastructure for these areas (GOT 2015b).

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

There is a need to rethink the basic framework governing investments in land, and the ways local communities, outside investors, and government policymakers interact. Currently the policy and legal framework of Tanzania fail to minimize the risks and negative impacts, as well as maximize the benefits and potential of land investments. Donors should support initiatives that clarify ambiguities and inconsistencies in the regulatory framework. This includes harmonizing the definition of “General land” in Tanzania’s Land Act and Village Land Act. Community rights should be emphasized by integrating the principle of free, prior, and informed consent in national legislation and regulatory frameworks; providing capacity building to local communities, including legal literacy training, paralegal programs, training in negotiating skills, and ensuring legal and technical support during the acquisition process; understanding potential impacts of donor programming designed to support land registration activities to ensure unintended harms to smallholders and vulnerable groups do not occur; establishing mechanisms to ensure participation of all members of the community, including groups that are often silent in community meetings such as women, young people, and any minority groups depending upon the context; and developing tools for monitoring and evaluating land deals, including databases and inventories in order to improve transparency.

Tanzania faces many challenges: from achieving food security to mitigating and adapting to climate change, protecting biodiversity while at the same time initiating economic growth. Land use planning is one of the tools that can help to meet these challenges because it helps people identify and negotiate future land and resource uses. Land availability and supply, especially in urban areas is, in part, contingent upon the efficient functioning of several processes including: (1) declaration and regulation of planning areas; (2) physical planning of land use through master planning or its alternatives; (3) detailed planning of residential, commercial and recreational layouts; (4) land development controls in urban and peri-urban areas; and (5) cadastral surveying. Improving these processes can help create more sustainable and inclusive cities. In rural areas, special attention should be paid to building the capacity of village governments to assist in land use planning and land management efforts to promote participatory planning and decision making. Reinforcement of the appropriateness of general boundary demarcation and mapping principles, as a suitable alternative to expensive and time-consuming cadastral surveys, is also seen as critical to supporting any significant scaling of land registration and regularization in Tanzania. Donors should support initiatives that build capacity for participatory, inclusive land use planning in urban areas and support efforts to build capacity that improves village-level land use planning and management. Every opportunity should be taken to reinforce the necessity of maintaining general boundary principles for rural land registration within Tanzania’s legal framework.

A significant hindrance to providing more secure to land rights is weak governance in land administration, particularly at the local level. There are a number of reasons for this including, but not limited to: availability of financial and material resources, capacity of human resources, complex procedures and multiple reporting lines, and overlapping decision making processes. Support for improvements in land administration cannot be expected in the absence of a functioning system of local government. Donors should support government efforts to decentralize land governance at the local level. The trend of decentralization and devolution of land administration and management creates the potential for more responsive and transparent governance. However effectively decentralizing and devolving land governance requires time and significant resource outlays. A significant part of this is in building human resource capacity in the land sector will have long-term payoffs. Where possible, donors should support training and professional development opportunities for government officials, civil society organizations, farmers’ organizations and others.

Tanzania is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world and is also endowed with various environmental resources including land, air, atmosphere, water, wildlife, forests, mineral resources, wetlands, renewable energy sources, and oil and gas. Despite advances in environmental law and policy use, the protection of valuable natural resources is constrained by inadequate human, infrastructure and financial capacity for managing environmental assets at all levels; low levels of awareness by the public on environmental issues; and weak enforcement and compliance with policies and laws. Donors should encourage strong measures to protect and manage these resources to ensure continued support a healthy society and sustainable economy and striking a balance between conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resource. These include involving key stakeholders for effective implementation and monitoring of relevant policies, legislation, strategy and plans; promote public awareness and participation on environmental management; strengthen the implementation of action plans and strategies, particularly by Local Government Authorities (LGA’s) Donors should also promote regional and international cooperation on environmental management and research and dissemination of findings on natural resources management and conservation.

Land rights in Tanzania have been the subject of vigorous debate and remain a contested and divisive issue. Typically, marginalized people and populations, including women and young people, have had difficulty claiming and retaining land rights. Donors should support efforts that further strengthen women’s land rights in Tanzania by addressing both legal and customary gaps. This can be done through legal reforms, research on de facto land rights for women, community awareness building, strengthening of farmers’ associations and by improving the agricultural value chain so that women will not lose land rights in the wake of large scale agricultural development initiatives.

Livelihoods for pastoralists are at risk with the loss of grazing land often attributed to increasing pressure from other users and lack of secure rights within the communal lands upon which they depend. The result has been an increase in land use conflicts between pastoralists and other land users. n. However, if pastoralist groups lack title over their lands and if villages don’t have enforceable land-use plans that define the kind of activities permitted in certain zones, such as settlement, grazing and agriculture, then pastoralist groups may be at risk of losing control of the lands and the resources they need to survive. Donors should support existing and proven approaches to secure communal land rights. CCROs are an effective tool for strengthening community land rights by granting formal recognition of customary land rights. In this way the collective nature of the title means that negotiations to plan for and accommodate pastoralists can only take place with the consent of the entire group, thus providing greater tenure security to at-risk communities and minorities. In addition, while CCROs historically granted parcels of land to individuals for farming, some places within Tanzania have modernized the tool to formally secure land for collective use such as livestock grazing.

Summary

After gaining independence from Britain in 1961Tanzania, under its first President Julius Nyerere, embraced African socialism. The authority of the state (and specifically the President) was reinforced to allocate and designate the uses of Tanzania’s natural resources. At the same time, individual and family customary land rights were largely abolished and were transferred to newly established elected village councils. Collective cultivation of the land was encouraged as rural people from scattered settlements were consolidated into communal (ujamaa) villages to promote large-scale collective farming. A change of government in1985 led to a reversal of this policy. Customary law and individualized rights to farmland were again recognized, and efforts were made to enact laws that would promote investment and increases in productivity, including by foreign investors.

After gaining independence from Britain in 1961Tanzania, under its first President Julius Nyerere, embraced African socialism. The authority of the state (and specifically the President) was reinforced to allocate and designate the uses of Tanzania’s natural resources. At the same time, individual and family customary land rights were largely abolished and were transferred to newly established elected village councils. Collective cultivation of the land was encouraged as rural people from scattered settlements were consolidated into communal (ujamaa) villages to promote large-scale collective farming. A change of government in1985 led to a reversal of this policy. Customary law and individualized rights to farmland were again recognized, and efforts were made to enact laws that would promote investment and increases in productivity, including by foreign investors.

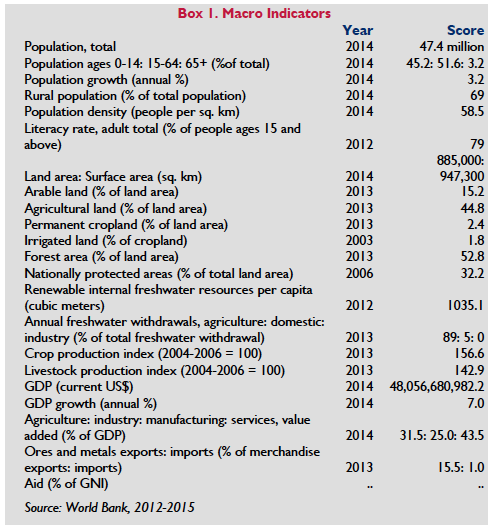

In many ways economic growth in the country is robust. Gross Domestic Product growth has averaged more 5 percent per year between 2007 and 2014 resulting in improvements in living conditions, access to basic education, health and nutrition and, labor force participation in non-agriculture employment. As of the last census in 2012, approximately 28.2 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, a reduction from 34 percent in 2007. However, these benefits have not been distributed equitably. Inequality has increased between the urban and rural population and approximately 12 million Tanzanians are still living in poverty. Additionally, not all Tanzanians are satisfied that the post-1995 framework provides a meaningful mechanism for the transparent and efficient purchase and sale of land, sufficiently supports gender equity, protects national interests in Tanzanian land and other natural resources, or fulfills its potential to support sustainable economic development.

Forty-four percent of Tanzania’s land is classified as agricultural and agriculture accounts for 24 percent of the GDP, 30 percent of total exports and 65 percent of raw materials for Tanzanian industries. Fifty-two percent of Tanzania’s total land area is classified as forest and it is one of the twelve mega-diverse countries of the world, endowed with natural ecosystems that contain a wealth of biodiversity. These resources are threatened by climate change, which has both impacted, and is impacted by, existing land use in Tanzania.

Approximately 90 percent of Tanzania’s poor people live in rural areas. At the same time by 2030, it is estimated that more than 25 million Tanzanians will be living in urban areas. The demand for urban land is significantly exceeding the formal supply—and the gap is widening. Expanding demand is resulting in escalating land prices, urban informality, and proliferating peri-urban development.

The Land Act of 1999 and the Village Land Act (VLA) of 1999 provide the overarching legal framework for land governance and administration. The two land laws establish three basic categories of land: General, Reserved and Village Land. General land is surveyed land that is usually located in urban and peri-urban centers such as legally designated municipalities. Section 2 of the Land Act defines general land as all public land which is not reserved land or village land and it includes unoccupied or unused village land. Reserved land includes that reserved for forestry, national parks, and areas such as public game parks and game reserves. Other categories of reserved land include land parcels within a natural drainage system from which water basins originate, land reserved for public utilities, land declared by order of the minister to be hazardous and public recreation grounds. The Land Act provides the legal framework for General Land and Reserved Land. Under the Land Act, only the Ministry of Lands, through the Commissioner of Lands, has the authority to issue grants of occupancy.

The Village Land Act provides the legal framework for village land. Under the Village Land Act, land is classified as: Communal land, Occupied land, and Vacant land. Village Land is managed by a Village Council elected by a Village Assembly. A Village Council is the corporate entity of a registered village; the Village Assembly includes all residents of a village aged 18 years and above. The Village Council is accountable to the Village Assembly for land management decisions. The Village Land Act gives village government the responsibility and authority to manage land, including issuing Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy within their boundaries and establishing and administering local registers of land rights. They must apply local customary law, provided it does not conflict with the prohibition of gender discrimination. Some village land has been demarcated but much still needs to be mapped and registered. While some legal experts in Tanzania have argued that villages can lease their lands directly to investors, this position is not universally accepted and is ambiguous under the VLA.

Tanzania’s land laws contain progressive elements in terms of recognizing customary land rights and granting them equal weight and validity to formally granted land rights. However, land insecurity in rural areas is high among small landholder farmers, pastoralists, and women. In urban areas, land is secured through formal and informal land transactions including land allocation from a municipality in an urban or peri-urban area and land purchase, but it is estimated that nearly 60 percent of urban dwellers live in informal settlements and lack tenure security. In general, women’s rights to land are relatively well supported in Tanzania’s formal legal framework. However, despite helpful laws, women continue to face the threat of losing their land as customary laws and norms favor male inheritance. Widowhood or divorce leads to some women losing their land to other, more powerful family members.

Global interest in investing in Tanzania’s rural and urban land has grown in recent years and hundreds of thousands of hectares of land have been acquired by companies in the biofuel, sugarcane, and forestry sectors. The formal land market is very limited and so while some investors follow formal procedures to obtain land rights others may obtain rights informally (without following the statutory processes for acquiring rights to land). In such cases investors may negotiate with traditional village authorities and local government bodies. Under the 1967 Land Acquisition Law the government may also convert lands held by villages to General Land to make it available to investors. If the investment fails, the land, once transferred to General Land, will not revert to back to Village Land because the customary rights that the communities have in Village Land are formally extinguished by the transfer. This leaves communities at risk.

Tanzania is rich in water, and natural resources. For the past decade, the resurgence in global demand for natural resources, including minerals, has been escalating, largely driven by foreign investors. The search for commercial natural resources is now expanding into more remote, and often extremely fragile, regions. At the same time Tanzania is the only country in the world to allocate more than 25 percent of its total area to national parks and other protected area status. It has 14 National Parks, 17 Game Reserves, 50 Game Controlled Areas, 1 Conservation Area, 2 Marine Parks and 2 Marine Reserves. It includes the second largest protected area in the world, the Selous Game Reserve, which is a World Heritage Site. With so much land protected for conservation purposes, and demands for resource exploitation expanding, the government needs to address how to handle competing demands for land to help mitigate or avoid conflicts over increasingly scarce land.

Land

LAND USE

Tanzania has a total land area of 885,800 square kilometers, including 2,643 square kilometers that comprise the Zanzibar archipelago. Tanzania shares borders with Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The mainland terrain includes highlands in the north and south and a central plateau. The country has large active and extinct volcanoes, including Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Meru in the north, and a block of ancient rock formations in the east known as the Eastern Arc. Coastal plains run along the 1300-kilometer coastline, and Lake Victoria, Lake Tanganyika and Lake Malawi have a combined 2300 kilometers of shoreline. The Zanzibar archipelago consists of two large islands (Unguja and Pemba) and several smaller islands collectively referred to as Zanzibar.

The mainland, known as Tanganyika, obtained independence from Britain in 1961 and Zanzibar followed in 1963. In 1964, the two regions combined to form the United Republic of Tanzania. Zanzibar has significant representation in the Union Government and is also semiautonomous, with its own president, legislature and bureaucracy and has separate legal frameworks governing land, water and forests (USDOS 2010). Zanzibar has experienced sectarian and political tensions in recent years and the contested 2015 Presidential election, resulting in another re-run election in 2016, has undermined the credibility of electoral processes on the island (Al Jazeera 2015).

Forty-four percent of Tanzania’s land is classified as agricultural, of which 14.3 percent is arable land, 2.3 percent is permanent crops, such as such as coffee, bananas and cassava and 27.1 percent is permanent pasture (World Bank 2014; Central Intelligence Agency, 2016). Agriculture is one of the leading sectors in Tanzania accounting for 24 percent of the GDP, 30 percent of total exports and 65 percent of raw materials for Tanzanian industries. The main food crops are maize, sorghum, millet, rice, wheat, beans, cassava, potatoes, bananas and plantains. Main exported cash crops are coffee, tea, cotton, cashews, raw tobacco, sisal, and spices. It is estimated that only 24 percent of about 44 million hectares of total lands are being utilized. Smallholder farmers primarily hold cultivated lands, with average farm sizes between 0.9 and 3.0 hectares.

After crops, the livestock industry is the second largest contributor to Tanzanian agriculture, representing 5.5 percent of the country’s household income and 30 percent of the Tanzania’s agriculture GDP. As with farming, livestock-raising is primarily undertaken by smallholder farmers (Tanzania Invest 2015). Pastoralists have used the rangelands in what is now Tanzania for hundreds of years, developing a land management system adapted to variable ecological, social and economic conditions. Pastoralists play a dominant role in this sector, contributing greatly to Tanzania’s economy: according to government records, pastoralists and agro-pastoralists rear approximately 98 percent of the country’s some 21 million cattle and 22 million small stock and produce most of the milk and meat consumed nationally. Pastoralists have been, and continue to be, permanently dispossessed of their land holdings, which has reduced the area available to them for livestock production (International Work Group For Indigenous Affairs, 2016b).

Climate change has both impacted, and is impacted by, existing land use in Tanzania. Regarding the former, agriculture is mostly rain fed and thus the success of activities in the sector remains highly sensitive to weather, especially rainfall. Over the last four decades, Tanzania has been hit by a series of severe droughts and flood events as a result of climate change. The consequences of climate change have been a reduction in agricultural production and greater food insecurity (FAO 2014). At the same time, unsustainable land management practices, including continuous cropping (with reductions in fallow and rotations), repetitive tillage and soil nutrient mining, overstocking, overgrazing, frequent rangeland burning, and over-use or clearance of woodlands and forest, are contributing factors in climate change (Gambino and Liwenga 2014).

Fifty-two percent of Tanzania’s total land area is classified as forest. Woodlands occupy about 93 percent of the forested area. The remaining 7 percent is composed of lowland forests, humid montane forest, mangrove forests, and plantations. These resources are currently facing a deforestation rate of 372,000 hectares per year, which results from heavy pressure from agricultural expansion, livestock grazing, wild fires, over-exploitation, and unsustainable utilization of wood resources and other human activities (FAO 2015).

As noted, Tanzania is one of the twelve mega-diverse countries of the world, endowed with natural ecosystems that contain a massive wealth of biodiversity. The country has six out of the 25 world-renowned biodiversity hotspots, hosting more than one-third of the total plant species on the continent and about 20 percent of the large mammal population (GOT 2015a). Tanzania has the second highest proportion of national protected areas, after Zambia. Twenty-eight percent of the country is set aside for national parks, conservation areas, game reserves, and controlled and protected areas (UNEP 2013).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

LAND DISTRIBUTION

As of 2014, Tanzania had a population of nearly 47.4 million people, 69 percent of whom live in rural areas (GOT 2014; World Bank 2015). It is a diverse country, with 120 tribal groups. Approximately 1.3 percent of the population lives in Zanzibar (GOT 2013). Population density varies widely and is highest in the mainland capital Dar es Salaam, followed by Mwanza, Mbeya and Morogoro, the fertile northern and southern highlands, along the shores of Lake Victoria, and in urban and coastal areas. The central region of the country, which has an arid climate and relatively poor soil, is the least populated.

Despite impressive GDP growth over the past decade, Tanzania still remains one of the world’s poorer countries in terms of per capita income. The sustained average annual GDP growth rate of 6 percent, double the average rate of the 1990s, masks disparities across sectors and geographical areas. No region is significantly better off than others and all are very poor by international standards – approximately 90 percent of Tanzania’s poor people live in rural areas. The agricultural sector, composed of a majority of smallholders, has not benefited from the same momentum as other sectors. The incidence of poverty is highest among those rural families who live in arid and semi-arid regions and who depend exclusively on livestock and food crop production (IFAD 2014).

Urbanization is well underway in Tanzania. The largest city, Dar es Salaam, on the country’s eastern coast, has an estimated 2.9 million people. It was the capital until 1996, when the capital was officially moved to the central city of Dodoma (estimated population 1.7 million) (World Bank 2012b). Dar es Salaam remains the commercial center of the country and many government functions continue to be performed there (including land administration). By 2030, it is estimated that more than 25 million Tanzanians will be living in urban areas and the percentage of people living in urban areas is likely to grow from 24 percent in 2005 to 38 percent in 2030 (World Bank 2012a). The urban poverty rate is 15.5 percent (World Bank 2012b)). Recent data suggests that 74 percent of Tanzania’s urban population lives in so-called Low-Income Areas (LIAs) (Komu 2014). Because the urban population is expected to grow at more than twice the rate of the population as a whole, the demand for urban land significantly is exceeding the formal supply—and the gap is widening (Pausche and Bruebach 2012). Urban land pressures have resulted in escalating land prices, urban informality, proliferating peri-urban development, and “land grabbing” (Komu 2014).

Global interest in investing in Tanzania’s rural and urban land has grown in recent years. In response to concerns related to some land transfers the Government of Tanzania in 2013 placed a cap on the amount of land that can be leased by foreign investors. Large-scale land acquisitions for agriculture, biofuels and forestry have encompassed significant amounts of land. For example, the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) is a multi-stakeholder partnership to rapidly develop the region’s agricultural potential. It was initiated at the World Economic Forum (WEF) Africa summit 2010 with the support of founding partners including farmers, agri-business, the Government of Tanzania and companies from across the private sector. The SAGCOT Center supports efforts to meet these objectives, including fostering inclusive, commercially successful agribusinesses that will benefit the region’s small-scale farmers, improve food security, reduce rural poverty and ensure environmental sustainability (SAGCOT 2016). The SAGCOT growth corridor, delineated by “cluster areas,” is being developed to attract and streamline appropriate investment. Cluster areas extend horizontally across the country from the western border to the eastern coast, covering approximately one third of Tanzania’s land mass (Taylor 2015). Hundreds of thousands of hectares of land have been acquired here by companies in the biofuel, sugarcane, and forestry sectors (Ngorisa 2015).

For decades, Tanzania has hosted the largest refugee population in Africa and is considered one of the world’s major refugee-receiving states. According to UNHCR, there are currently 253,190 refugees in the country; Burundian and Congolese refugees comprise the majority. Additionally, the current instability in Burundi has increased the number of individuals seeking refuge in the country (International Refugee Rights Initiative 2015). Many of these camps are located in the northwest regions of the country, including Kigoma, Katavi, and Tabora (UNHCR 2015). Tanzania also hosts a large population of urban refugees. The government estimates the number of refugees in Dar es Salaam alone to be at least 10,000 (Pangilinan 2012).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution of Tanzania (1977, as amended, 1998) provides that every person has the right to own property and the right to have his or her property protected in accordance with the law (GOT Constitution 1977). The 1995 Land Policy reaffirmed that all land in Tanzania is considered public land vested in the President as trustee on behalf of all citizens and established the fundamental principles guiding land rights use and management, which maintained centralized control of land. The Policy recognizes rights based longstanding occupation of land; it encourages productive and sustainable use, notes that women have the same rights to land as men and promotes transparency and citizen participation in decision making related to land.

The Land Policy was followed by the adoption of the Land Act and Village Land Act in 1999, both of which are currently under review for formal amendment (as of 2016). Tanzania’s Land Act classifies land as: (1) Reserved land (2) Village land and (3) General land. Reserved land includes statutorily protected or designated land such as national parks, land for public utilities, wildlife reserves and lands which, if developed, would pose a hazard to the environment (e.g., river banks, mangrove swamps). Village land includes registered village land, land demarcated and agreed to as Village land by relevant Village Councils, and land (other than reserved land) that villages have been occupying and using as village land for 12 or more years (including pastoral uses) under customary law. All other land is classified as General land. General land includes woodlands, rangelands and urban and peri-urban areas that are not reserved for public use. Under the Land Act, general land includes unoccupied or unused village land. General land and Reserved land are governed by the Land Act of 1999, whereas Village land is governed by the Village Land Act of 1999.

The Land Act stipulates that a non-citizen shall not be allocated or granted land unless it is for investment purposes as provided for under the Tanzania Investment Act (GOT 1997). The Tanzania Investment Act does not apply to investments in mining and oil exploration (GOT 1997). Whether or not the corporate body is registered in Tanzania, if the majority shareholders or owners are non-citizens, then it remains a foreign corporation and therefore cannot receive a granted right of occupancy. However, there is a conflict of between the Land Act and Companies Act (GOT 1999a; GOT 2002). The Companies Act provides that any company incorporated under the Companies Act shall have the same power to hold land in Tanzania, which is in direct contradiction to the Land Act. In principle, the Land Act takes legal precedence over the Companies Act (Lui 2014).

Village land is governed by the Village Land Act of 1999. Under this Act, land is classified as: (1) Communal land (e.g., public markets and meeting areas, grazing land, burial grounds); (2) Occupied land, which is usually an individualized holding or grazing land held by a group; and (3) Vacant land, which is available for future use as individualized or communal land (specifically encompassing unoccupied land within the ambit of village land, as opposed to general land). The Act does not recognize grazing land as a separate category, but pastoralists can assert customary rights of occupancy to grazing land (GOT Village Land Act 1999b). Foreigners who wish to occupy and use village land for various purposes can apply to the Village Council for the right to use the land and the Council may grant the non-citizen the right to use and occupy land for a limited period of time and under stipulated conditions.

In Zanzibar, all land was vested in the government in 1965. The Land Tenure Act of 1992 provides that the government can grant rights of occupation, which are perpetual and transferable. The government can cancel the occupation-right if the holder fails to use the land in accordance with good land use principles. The government also retains the right to approve any transfer of land rights under the Land Transfer Act of 1994. Most land-occupancy rights have not been registered and are held and transferred under principles of customary and Islamic law (Mirza and Sulaiman 1998; Jones-Pauly 1998).

Tanzania’s land laws contain progressive elements: they recognize customary land rights and grant them equal weight to formally granted (statutory) land rights (Sec. 18[1] Village Land Act 1999b). The law also devolves decision making at the village level, primarily through the Village Council, an elected body which is required to have 25 percent women members. However, critics of the laws, including Issa Shivji, chair of the Land Commission, contend that the laws actually make large-scale land takings and acquisition easier: for example, government authorities have centralized some elements of land administration, management and allocation in the executive branch of the government (Salcedo-La Viña 2015).

TENURE TYPES

Although a majority of land in Tanzania is held under customary tenure arrangements, all land in Tanzania is considered public land, which the President holds as trustee for the people. The Land Act places ultimate land ownership— “radical title”—in the president as a trustee for all Tanzanians, making land tenure a matter of usufruct rights as defined by various leaseholds. The government retains rights of occupancy, the imposition of development conditions, land rent, and control of all aspects of land use and ownership. Only the Ministry of Lands, through the Commissioner of Lands, has the authority to issue grants of occupancy. It also restricts non-nationals from acquiring land, except acquisitions connected to investments that have approval from the Tanzania Investment Corporation under the Tanzania Investment Act of 1997 (GOT 1999a; World Resources Institute and Landesa 2010).

The Village Land Act recognizes the rights of villages to land held collectively by village residents under customary law. Village land can include communal land and land that has been individualized. Villages have rights to the land that their residents have traditionally used and that are considered within the ambit of village land under customary principles, including grazing land, fallow land and unoccupied land. Villages can demarcate their land, register their rights and obtain a Certificate of Village Land (CVL) (GOT Village Land Act 1999b; World Bank 2010) by working with the appropriate District Land Office. The village government has the responsibility and authority to manage land, including (in conjunction with the appropriate District Land Office) issuing Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy within the village boundaries, and establishing and administering local registers of village land rights. They must apply local customary law, provided it does not conflict with the prohibition on gender discrimination (GOT Village Land Act 1999b).

The process of issuing Certificates of Village Land to registered villages has been slow. However, as of 2014, and with help from World Bank funding approximately 10,000 CVLs had been issued (World Resources Institute and Landesa 2010; Bruce 2014).

Customary Right of Occupancy. Villagers have a customary right of occupancy for village land that they hold under customary law or have received as an allocation from the Village Council. A CCRO issued by the Village Council to individual villagers affirms customary occupation and use of land by owners, once signed by the Village Chairperson, the Village Executive Officer and the owner, it must be signed and registered by the District Land Officer for final distribution to villagers. Customary rights of occupancy can be held individually or jointly, are perpetual and heritable, and may be transferred within the village or to outsiders with permission of the village council. Village land allocations can include rights to grazing land, which are generally shared. The Village Council may charge annual rent for village land (GOT Village Land Act 1999b).

Granted Right of Occupancy. Granted rights of occupancy are available for General and Reserved land, subject to any statutory restrictions and the terms of the grant. Granted Rights of Occupancy are obtained through the Commissioner on Lands, who is appointed by the President. Grants are available for periods up to 99 years and can be made in periodic grants of fixed terms. Granted land must be surveyed and registered under the Land Registration Ordinance and is subject to annual rent. Squatters and others without granted rights may have customary rights to occupy general land, which may be formalized with a residential license or remain informal and insecure (GOT Land Act 1999a).

Leasehold. Leaseholds are derivative rights granted by holders of granted or customary rights of occupancy. Holders of registered granted rights of occupancy may lease that right of occupancy, or part of it, to any person for a definite or indefinite period, provided that the maximum term must be at least ten days less than the term of the granted right of occupancy. Long-term leases shall be in writing and registered. Short-term leases are defined as leases for one year or less; they may be written or oral and need not be registered. Holders of customary rights of occupancy may lease and rent their land, subject to any restrictions imposed by the Village Council (GOT Land Act 1999a). Foreigners may lease land through long term leases or joint ventures. Using a long lease, a foreign investor will enter into a lease with local land owners for the most part of the term of right of occupancy of that land, save for few days less that term of occupancy. It is worth noting that granted rights of occupancy have a term of up to 99 years with an option of renewal. Under a joint venture arrangement, a foreign company may own up to 49 percent of an entity (a Tanzanian entity must own at least 51 percent of the entity) in which case the joint venture will be allowed to enjoy use of land as a Tanzanian company.

Residential license. A residential license is a derivative right granted by the state (or its agent) on General or Reserved land. Residential licenses may be granted for urban and peri-urban non-hazardous land, including land reserved for public utilities and for development. Residents of urban and peri-urban areas who have occupied their land for at least three years at the time the Land Act was enacted had the right to receive a residential license from the relevant municipality, provided they applied within six years of the enactment of the Land Act (i.e., by 2005) (GOT Land Act 1999a).

In Zanzibar all land is public and vested in the Government. Clove and coconut farms were nationalized and the land apportioned in the Three Acre Plots (TAP) and distributed to peasants, with a caveat that they could not transfer ownership or inheritance rights. Most rural land is either under individual or state ownership. Some of the TAPs have been sold as granted parcels, changed into residential/ commercial lands, been subdivided, or been inherited contrary to provisions of the decree. Based on various sources (e.g. agricultural census data and numbers from the TAP program, less than 10 percent of these parcels were formally (digitally) registered (Bjørn and Sæbø 2015; Lugoe 2012).

Despite laws that prohibit foreigners from owning land, non-residents can obtain land tenure rights of use and occupancy through derivative rights, lease, joint venture, and use rights granted by Village Councils. Derivative rights may be granted to investors wishing to have rights to occupy and use land by the Tanzania Investment Centre (TIC) for a specified amount of time, which cannot exceed 99 years. The TIC grants the investor the derivative right to use and occupy the land, that is classified as General Land. If the investor fails to implement the investment as applied to the TIC, the TIC may re-acquire the land from the investor and the investor will be entitled to be paid compensation for any development made on the land. Foreigners can also enter in lease agreements with Tanzanian citizens who have been granted right of occupancy, provided that the maximum term for which any lease may be executed is less than ten days of the period for which the right of occupancy has been granted. Joint venture agreements between foreign and incorporated companies in which citizen(s) are major shareholders are able to acquire granted right of occupancy, which enables them to use the acquired land for the purposes of the company business. Finally, non-citizens can be granted use rights by Village Councils for a limited period of time under stipulated conditions as indicated by the Village Council and the Village Land Act (Liu 2014; GOT Village Land Act 1999b: GOT Land Act 1999a).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Smallholders and Rural Residents

Village Land constitutes nearly 70 percent of all lands in Tanzania and is defined as a) land either originally described as the village area or so demarcated since then; b) land of a given village according to agreement between that village and its neighbors; and c) any land which villagers have been using or occupying for the past 12 years. Village Land at the village level is formally registered by obtaining a Certificate of Village Land, although the Village Land Act provides that villages without this certificate possess customary rights over land, which falls within the definition of Village Land. Once a village has a CVL then villagers can apply for Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy.

For those living on Village Land, the most common means of obtaining access to land is through inheritance, gifts, borrowing from family members, and land allocations, including leases from village councils. Where land is abundant, an occupier can take possession by clearing and cultivating the land. The most important procedure for enhancing rural land rights is by obtaining a Certificate of Customary Right of Occupancy (CCRO). There are five steps for a villager or non-villager to obtain a CCRO; these are: 1) the landowner submits an application for a certificate to the Village Council, which may be accompanied by information about parcel boundaries; 2) The Village Council reviews the application (if any disputes over land exist the Village Land Adjudication Committee may need to review and, if possible, resolve these); 3) the Village Council issues a letter of offer which stipulates fees, development conditions, yearly rent and other conditions; 4) the landowner submits a written agreement to these conditions on a prescribed form; and 5) the Village Council issues a certificate of “Customary Right of Occupancy.” (GOT Village Land Act 1999b: Mugabe 2013; World Resources Institute and Landesa 2010). In addition, the villagers must work with the Village Council and the appropriate District Land Office to have their landholdings surveyed as part of the CCRO process. Tanzania does not currently support systematic land registration; rather registration proceeds on a “spot” adjudication basis. Donors including USAID, through its Mobile Applications to Secure Tenure (MAST) and Land Tenure Assistance (LTA) activities, have sought to support more systematic adjudication efforts.

Land insecurity in rural areas is highest amongst small landholder farmers, pastoralists, and women (Mugabi 2013). Smallholder farmers have been most vulnerable to tenure insecurity due to large-scale land deals and land acquisition. Since 2005 “land grabbing” issues have returned to prominence in Tanzania’s social and political discourse, as global demand to produce biofuels triggered a wave of controversial land acquisitions in the country by foreign companies. The underpinnings of these large-scale land acquisitions are complex and diverse and include: internal politics, corruption, foreign demand, undervaluation of land and other private assets, and land speculation (Anseeuw et al 2012; Cotula et al 2008). The existing legal framework and the limited capacity of the government to register and enforce rights means the tenure security of village landholders is a continuing issue (Sulle and Nelson 2012; Nelson et al 2012).

Because foreigners cannot own village land, for a foreign company to acquire rights to a parcel of land, pre-existing customary rights to that parcel must be extinguished. This is done through the transfer of Village Land to ‘General Land’, for which a derivative right can be issued by the Tanzanian government. The transfer of land from Village to General categories can only be done by Presidential assent, and compensation, paid only once, must legally be agreed to and given prior to the transfer. If the investment fails, the land, once transferred to General Land, will not revert to back to Village Land, because the customary rights that the communities have in Village Land are formally extinguished. As a result, when foreign companies acquire land for investment purposes, local communities permanently lose their land rights. In some cases, this means that local communities bear perhaps underappreciated risks associated with these commercial investments, in that they permanently lose their key livelihood assets of land (Songa 2015; Nelson et al 2012; Curtis 2015).

Pastoralists

Other causes of insecurity include migration of people in search of land for livelihoods and changes in land use that encroach on existing residents. In Tanzania there are approximately 1.5 million pastoralists spread among five pastoral tribes and communities, with the Maasai being the largest and most well-known. Pastoralists face a number of acute challenges including a shortage of land for grazing (Maliasili Initiatives 2012). Livestock owners can obtain land for grazing under customary law, through a recognized right of customary use under the Village Land Act or by a specific land allocation by the Village Council. However, conflicts over land access prevail due to increased population pressures and the diversification of land use patterns in Tanzania (i.e. expansion of settled and ranching farming, national parks, towns and settlements (Sendalo 2009). Further, pastoral organizations point out that pastures that are lawfully granted may be perceived as idle or bare land and identified for investment purposes (IWGIA 2016b). Additionally, a large part of the land areas used for pastures fall under the category General Land, which is under the exclusive control of central government. Finally, women in rural areas, despite an equitable law, face the risk of losing their land, or having a legal claim to land brought against them. The reasons are broad and varied: customary laws favor male inheritance; widowhood or divorce can lead to some women losing their land to other more powerful family members; high demand for land in peri-urban and fertile agricultural areas has resulted in sharp increases in its commercial value and a great incentive to sell (generally men make these decisions); and the generally patrilineal culture of the country has left women with little voice and land insecurity (Dancer 2015).

Urban Issues

In urban areas, land is secured through both formal and informal land transactions including land allocation from a municipality in an urban or peri-urban area, land purchase, and squatting. Formal land titling in cities is difficult for the poor to access due to complicated procedures and costs of application. As a result of sustained informal growth, over 60 percent of the urban population lives in informal settlements, or slums (UN-HABITAT, 2010). As a result of the Tanzanian government’s ambitious attempt to deal with informality, a large-scale effort was launched in 2005 to bring millions of urban residents onto the formal land registry for the first time by issuing land titles known as “residential licenses.” These licenses were sold cheaply, without the costs and delays of cadastral surveying, identified the rightful owner of the land, provided a guarantee against government expropriation for a fixed term (initially five years), and were not transferrable and, therefore, could not be foreclosed upon by banks. While it is believed that participants did enjoy increased tenure security, the short length of the guarantee (and the prohibition on transfer) might explain why the residential license program eventually failed to gain traction, and why the benefits often associated with land formalization do not appear to be fully emerging in this setting (Colin et al 2015).

Women, children, and refugees are among cities’ most tenure insecure residents. Women have particular difficulties securing and retaining urban housing, a problem made more acute by a housing crisis. Laws and practices are discriminatory relating to inheritance, ownership, mortgage, and divorce. Patriarchal attitudes are entrenched, as regards titling, land, and renting or selling to single women. As a result, women spend significantly more time in informal settlements living in poor quality housing. In addition, they experience more acutely the lack of basic services, and are more exposed to gender-based violence and health risks (Hughes, K., & Wickeri, E., 2011). One in four children lives in a city and the vast majority of urban children suffer from social, physical and environmental problems specific to cities, including overcrowded and sub-standard housing in areas exposed to hazards and a lack of safe places to gather and play (UNICEF 2012). The country also hosts a population of refugees who live outside camps as ‘spontaneous,’ ‘self-settled’ or ‘urban’ refugees. Among urban refugees, the government estimates the number in Dar es Salaam alone to be at least 10,000 (USDOS, 2012). These refugees lack legal recognition as refugees by the Tanzanian government and do not have access to humanitarian aid or resettlement assistance and most fear being identified as refugees. Livelihood and coping mechanisms are curtailed by their lack of legal status and inability to obtain formal permission to reside in Dar es Salaam (Panglinian 2012; Asylum Access 2012).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

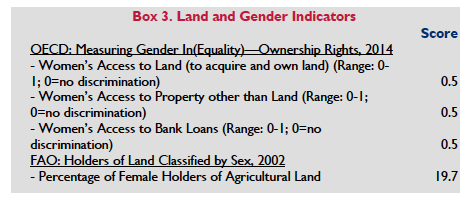

In general, women’s rights to land are relatively well-supported in Tanzania’s formal legal framework: The Constitution and formal law provide for equal rights to property and prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex (GOT Constitution 1977). Tanzania’s 1999 Land Act expressly states that women shall have equal rights to obtain and use land, and that customary law cannot be used to discriminate against women. The legal framework for land rights also provides for women’s representation in governing bodies.

In general, women’s rights to land are relatively well-supported in Tanzania’s formal legal framework: The Constitution and formal law provide for equal rights to property and prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex (GOT Constitution 1977). Tanzania’s 1999 Land Act expressly states that women shall have equal rights to obtain and use land, and that customary law cannot be used to discriminate against women. The legal framework for land rights also provides for women’s representation in governing bodies.

The Village Land Act provides that women must comprise at least 25 percent of the 15-25-member Village Councils. Many of the land-allocation programs have included specific requirements for including widows and women-headed households among the land recipients. Tanzania’s Marriage Act (1971) is also relatively progressive. The Act requires registration of both monogamous and polygamous marriages. Married women are permitted to hold property individually, and polygamous wives have individual rights to hold property. Married couples are presumed to hold land jointly; marital property is co-registered, and spousal consent is required when marital property is transferred or mortgaged (GOT Land Act 1999a; GOT Village Land Act 1999b; Tanzania Law of Marriage Act, 1971). Tanzania has also signed onto a number of international rights conventions that uphold property rights for women and girls including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW); the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC); and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa.

Despite these legislative pronouncements, in practice, national and international laws providing for women’s equal property rights are often not followed. For some issues, like inheritance, a body of conflicting and discriminatory law continues to exist. The lack of legal clarity is used to reinforce customary traditions that harm women and patriarchal practices predominate whereby men are de facto heads of households and have greater rights to land than do women (Duncan 2015).

In rural areas in particular, knowledge of the land laws is not widespread, and even where the formal laws are known, customary law and religious practices continue to govern how land is accessed and transferred. Most women access farmland from their natal families. If a woman’s clan follows a patrilineal and patrilocal system, as does the majority of the population, she will move to her husband’s village when she marries and will cultivate his land and the land of his family. A woman’s rights to the land thus depends upon her marriage, and these rights are usually lost if she divorces or becomes widowed. In matrilineal societies (a minority of the population, located primarily in the central and southern regions of the country), assets traditionally passed through the woman’s line, but male family members often controlled the assets, including land. Matrilineal systems that include matrilocal marriage (husband moves to wife’s village) tended to have the most egalitarian distribution of assets, but patrilineal/patrilocal (wife moves to husband’s village) systems have become increasingly favored. For the 35 percent of the country’s women who are Muslim, Shari’a law provides them with one-half the share of men, and a widow with children receives a one-eighth share of her deceased husband’s estate (one-fourth if there are no children) (FAO 2010a; Benschop 2002).

As a result of customary practices, which require women to access land through their fathers, brothers, husbands, or other men who control the land, women are rendered vulnerable. If she loses her connection to this male relative, either through death, divorce or migration, she can lose their land, home and means of supporting themselves and their families. Where women do have access to land, many studies show that women are allocated the smallest and least productive plots (Deere et al 2012; FAO 2011). The country’s proposed new constitution, which provides women with equal rights to own and use land, would override the current customary practices that weaken women’s rights to land (Mushi 2014). However, as of mid-2015, a referendum vote on the new Constitution had been delayed (Reuters 2015).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The President of Tanzania serves as the trustee of all land and is responsible for allocations of General land. The Ministry of Lands and Human Settlement Development (MLHSD) generally executes these responsibilities. The mandate of the Ministry is to facilitate the effective management of land and human settlements development services for the social and economic well-being of the Tanzanian society. The Ministry houses the Departments of Land Administration, Survey and Mapping, Physical Planning, and Housing. It directs the establishment of land policy and planning and is responsible for administering Reserved land and General land, including the allocation of granted occupancy rights and management of the country’s land resources. Core sector units also include Registration of Titles, Property Valuation, and District Land and Housing Tribunal (GOT 2016a). A Commissioner of Lands executes most of the Ministry’s responsibilities (GOT Land Act 1999a and GOT 2016b). The Land Commissioner’s functions include: overseeing implementation of the Land Acts; managing land acquisition, revocation and transfer processes; facilitating land development projects; overseeing administration of General land; and resolving land disputes administratively. There are three sections within the office of the Land Commissioner: Urban Land Administration Section, Rural Land Administration Section, Land Administration Legal Services Division and seven Zonal Land Administration Offices. Each section and Zonal Land Administration Office is led by an Assistant Commissioner (GOT 2016b).

Tanzania’s 30 regions are divided into districts and subdivided into divisions (Tanzania Daily News 2012). Within the Tanzanian context, therefore, decentralization is the transfer of responsibility from the Central to the Local Government. The Decentralization-by-Devolution policy was initiated in 1996 after being endorsed by the government in the Policy Paper on Local Government Reform. The reforms contained in the policy paper clearly laid out policy of devolution of functional responsibilities versus the earlier de facto de-concentrated approach to governance, which had continued to persist despite the reintroduction of elected local governments.

On the mainland, urban authorities consist of city councils, municipal councils and town councils. The rural authorities are the district councils, township councils and village councils. District councils coordinate the activities of the township authorities and village councils, approve village council bylaws and coordinate land use planning district-wide (GOT 2016a). Decentralization within the country in general and within land administration specifically, is now under way in the context of a locally empowered though centrally planned and implemented extension of land registry services, closely tied to the program of systematic adjudication and registration of land rights. During this most recent wave of land reforms Tanzania has been attempting to uphold customary land rights and develop a formalized universal land administration system that encompasses village (customary) lands (Fairley 2012). Administration and management of land is decentralized to the Village level, and is addressed by the Village Land Act, 1999. The Act mandates two local authorities to administer and manage village land: the Village Council and the Village Assembly. The Village Councils have the responsibility for formulating Village Land Use Plans for their areas, managing village forest reserves and collecting revenue including any land rents. Village Councils are elected by the Village Assembly, which includes all adult residents. One-quarter of the council must be female. The urban and district councils are comprised of members elected from each ward (wards are the government unit above villages), plus women appointed by the National Electoral Commission in proportion to the number of elected positions held on the council (not less than one-third).

A village adjudication committee marks land boundaries, sets aside land for rights-of-way and settles boundary disputes between villagers. The power of allocation of village land by the Village Council is, however, subject to the approval of the Village Assembly, which is the supreme authority on all matters of general policy-making in relation to the affairs of the village. It has been observed that de facto allocation of land occurs by Village Councils without approval of the Village Assembly for two main reasons: First the Certificate of Village Land gives power to the Village Council to manage village land. At the same time the legal requirement that they manage land as trustees of the villagers and with the consent of the Village Assembly is unclear to them due to lack of public information and training (Luhulu 2015, Van Gelder 2010).

Although the current land governance structure is designed to foster decentralized land administration, the central government continues to exercise significant authority over land through the Land Commissioner and, to a lesser extent, the District Councils and District Land Offices. (GOT Village Land Act 1999b). (GOT Village Land Act 1999b). For example, there is an unclear division of labor between the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements and village land authorities. Resource supports to village authorities to make their land institutions operate as prescribed by law is not sufficient. Finally, although the legal framework requires consultation with the Village Council, but Council approval is typically assumed. In many areas, Village Councils are also constrained in exercising their authority and responsibilities by their lack of knowledge – of the land laws and procedures generally, and obligations regarding women’s land rights in particular (GOT Village Land Act 1999b; Luhulu 2015).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

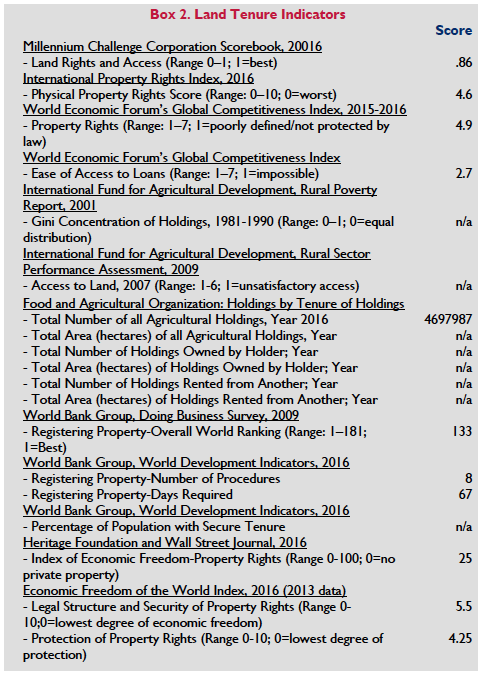

There is a very limited formal land market in Tanzania, and little information is available concerning its operation. Much of this is a reflection of problems associated with land registration. As of 2014 only three percent of the land in Tanzania has been registered and most of what is registered is in urban areas. Only 7.7 percent of villages have developed land use plans. In principle, rights of occupancy can be bought, sold, leased and mortgaged in Tanzania.

Primary constraints to development of the formal land market include: (1) the requirement for pre-sale notification of the Land Commissioner about the intended transaction; (2) the requirement that the Commissioner acknowledge such notification as a condition for registering the transaction; (3) prohibition of sale of land rights held for less than three years; and (4) the ability of the Land Commissioner to void a land transaction anytime within two years of the transaction if the Commissioner has reasonable cause to believe there has been fraud, undue influence or lack of good faith in the transaction (GOT Land Act 1999a; GOT Village Land Act 1999b; Sundet 2005; Kironde 2006). A holder of a customary right of occupancy can sell the right, subject to the approval of (and subject to any restrictions imposed by) the Village Council. Formal law regulates mortgages, and land rights must be registered before they can be mortgaged (Sundet 2005; Kironde 2006; GOT Land [Amendment] Act 2004).

The fundamental constraint to a robust land market is a lack of secure land titles (both statutory and customary) and an abundance of unsurveyed land. For example, data from the Bank of Tanzania suggests that 75 percent of land is not surveyed in Dar es Salaam. The market is also constrained by long, costly, and uncertain land registration processes. Tanzania ranks 123 of 189 economies in terms of ease of registering property on the World Bank’s 2015 Doing Business Report. It takes eight procedures and 67 days to register a property, at a cost of 4.5 percent of the property value, almost three times longer than the time it takes in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, but comparable in terms of cost. (World Bank 2015b; Centre for Affordable Housing Finance Africa 2015). However, efforts to improve land registration processes such as utilizing the Fit For Purpose Framework( FFP) a concept that encompasses a dynamic interaction of the spatial, legal, and institutional frameworks has enabled Tanzania to implement new and participatory approaches for capturing land rights information, as well as a lower cost methodology for quickly building a reliable database of land rights as an alternative to more traditional, and more costly, land administration interventions (USAID 2014).

A land market does exist for non–residents, through lease, and for domestic investors. However, Section 4 of the Village Land Act, confers to the President the right to transfer Village land to General or Reserved land for purposes of “investments of national interest.” This provision is viewed as essentially compulsory acquisition with some decision-making yielded to the village community. Further, Village lands not under cultivation or permanent settlement, or set aside for grazing, commonage, or for future use or population expansion may be easily by interpreted by government authorities as “unoccupied” or “unused” and made available to investors. The Land Act’s does not explain what the terms “unoccupied” or “unused” mean, and the phrase does not appear in the definition within the law. The result is a legal loophole that makes village land susceptible to allocation to outsiders (Makwarimba and Ngowi 2012).

The Tanzania Land Bank Scheme was created under the Investment Act; it identifies land as suitable for investment and the Tanzania Investment Centre acts as the broker for investors. The Land Bank was considered generally unsuccessful because the parcels it holds are too few, too small, and too scattered to be of much interest (Makwarimba and Ngowi 2012).

As a result of these issues, most land transactions, both urban and rural, occur on the informal market, and these tend to be leases. In rural areas, land sales were historically conducted between members of families or clans; landholders tended not to sell rights to buyers from outside the village. Since the end of the villagization project, and in keeping with the growing commoditization of land, the informal market has expanded; there is increasing demand for land in productive areas and areas with high potential for commercial development. In some cases, investors and land speculators follow formal procedures to obtain land rights, but in many cases buyers proceed informally, negotiating with traditional village authorities and government bodies, with the transaction evidenced by an informal deed signed by representatives of the official or traditional village authorities (Centre for Affordable Housing Finance Africa 2015).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The Constitution allows for the State to compulsorily acquire property for a list of broadly defined public purposes, including “enabling any other thing to be done which promotes, or preserves the national interest in general” (GOT 1977). The Land Act (1999), the Land Acquisition Act (1967) and the Urban Planning Act (2007) give the President overwhelming powers to acquire land needed for public use or interest. Compulsory acquisition laws stipulate that persons whose land is expropriated for public interest have to be fairly and promptly compensated. The compensation payable to dispossessed persons is based on the market value of the property or land. The spirit of the compensation is to ensure that affected households neither lose nor gain as a result of their land or property being appropriated for public interests (GOT Land Act 1999a; the Land Acquisition Act 1967; Urban Planning Act 2007; Kombe 2010). Compulsory acquisition was used during the process of moving the capital of the country from Dar es Salaam to Dodoma.

The Land Acquisition Act of 1967 and the Land Act of 1999 govern compulsory acquisition. Both include “development of agricultural land” as a valid public purpose for the State to acquire land compulsorily, leaving the door open for wide application of the state’s acquisition authority in the face of increased commercial interest in land investment in Tanzania. The 1970–1977 villagization program was based on the President of Tanzania’s authority to acquire and reallocate land. Hundreds of thousands of Tanzanians were resettled in the 1970s to implement a public policy of communal production and shared labor. The 1977 Constitution of Tanzania (as amended in 1998) provides some protection against the introduction of similar programs, mandating that no one can be deprived of property for purposes of nationalization or other purposes except in accordance with law and upon the government’s payment of fair and adequate compensation. However, the Constitution, the 1967 Land Acquisition Act, and land laws of 1999 do permit the President to acquire General, Village or Reserved land for public purposes. As noted, public purpose is defined broadly and includes public works, commercial development, environmental protection and resource exploitation (GOT Constitution 1977; GOT Land Acquisition Act 1967; GOT Village Land Act 1999b; GOT Land Act 1999a).

The laws governing land acquisitions state that the government must give landholders at least six weeks’ notice of the acquisition, but provide that the President has the discretion to shorten this notice period. The government must promptly pay landholders fair compensation, including annual interest of 6 percent for any delay in payment. The Land Act identifies seven factors to be considered in determining fair compensation: (1) the market value of the property; (2) disturbance allowance; (3) transport allowance; (4) loss of profits or accommodation; (5) cost of acquiring the subject land; and (7) any other cost loss or capital expenditure incurred in the development of the subject land. The government can offer landholders alternate land in lieu of or in addition to monetary compensation (GOT Village Land Act 1999b; GOT Land Act 1999a).

In practice, land expropriation is often not conducted in accordance with legal requirements. In some cases, the government converts Village land to General land to make it available to investors without paying villagers adequate compensation and without requiring or encouraging joint ventures or other local community participation in land development and enterprises. In addition to failing to compensate cultivators for the value of annual harvests lost, government compensation may fail to compensate other users of land, such as pastoralists and users of forest resources. Pastoralists in particular have lost land to tourism development, national park expansion, and infrastructure development. In some cases, investors have circumvented the requirement for government land expropriation and dealt directly with villages. Village Councils may be incentivized to negotiate directly with investors rather than wait for government intervention because the councils have an opportunity to set annual rent and request premium payments from the investors (World Bank 2010; Kironde 2009; Pallotti 2008; Hakiardhi 2009).

Compulsory acquisition practices also impact cities, especially the urban poor. In recent years, the urban landscape has been transformed in Tanzania. Despite the fairly small proportion of the population that lives in cities, the proliferation of informal land markets, land grabbing, speculation and expropriation. As a result, land values and speculation have been increasing persistently without providing an alternative resettlement area or paying fair compensation. The livelihoods of many households are more precarious. For example, urban farming, which promotes food security for residents, is threatened, and land-related conflicts have intensified especially in the peri-urban areas (Kombe 2010).

In both rural and urban settings, the Land Acquisition Act does not provide any specific protection for women or spouses. Women have been disproportionately affected by acquisitions in terms of land based, livelihoods, ability to feed their families, loss of water rights and general disempowerment. Widowed and single women have been even more impacted, as relocation has proven extremely difficult for them (Matupo 2015).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Persistent and escalating land disputes and conflicts are a feature of both rural and urban areas. In rural areas, conflicts are tied to increasing population pressure and the diversification of rural land use patterns (i.e. expansion of settled and ranching farming, national parks, towns and settlements); competition for natural resources such as land, water and minerals; conflicts over land uses, such as grazing versus cultivation; demarcation of village boundaries and allocation of common resources; promotion of commercial development; and adoption of land use plans that deny local communities access to land and natural resources needed for livelihoods (Kombe 2010; Chachage 2010). In some cases, disputes have become violent. For example, since 2015 violence in the Morogoro region between Masaai and Datoga citizens has resulted in burned villages, assaults, confiscations of livestock and property, and deaths. Though characterized as “ethnic conflict,” observers have stated that the conflict is the result of a series of attempted land grabs, where people have used their political influence to access the wetlands in Mabwegere and Kambala Villages. It is reported that the violence against the Maasai is well organized and financed by politicians, public servants and other well-connected people with economic interests in the land currently belonging to the Maasai community (IWGIA 2015).

In rural areas both formal and informal tribunals have jurisdiction to hear land disputes under Tanzania’s formal law. The Courts (Land Disputes Settlements) Act of 2002, the Land Act and the Village Land Act recognize the jurisdiction of informal elders’ councils, village councils and ward-level tribunals. Village Councils can establish a land adjudication committee, with members elected by the Village Assembly. The primary mode of dispute resolution in these forums is negotiation and conciliation. Forums provide a mechanism for local level dispute resolution. If disputes cannot be solved with Land Adjudication Committees, then cases may be taken to ward-level tribunals and/or to courts. Local forums may, however, reinforce existing hierarchies, and women and socially marginalized people may obtain less equitable results than if they had brought their claims in other tribunals. Nonetheless, many people prefer the rapid and socially legitimate results that can be achieved using local relationships and institutions (Odhiambo 2006; Odgaard 2006).