Published / Updated: May 2017

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

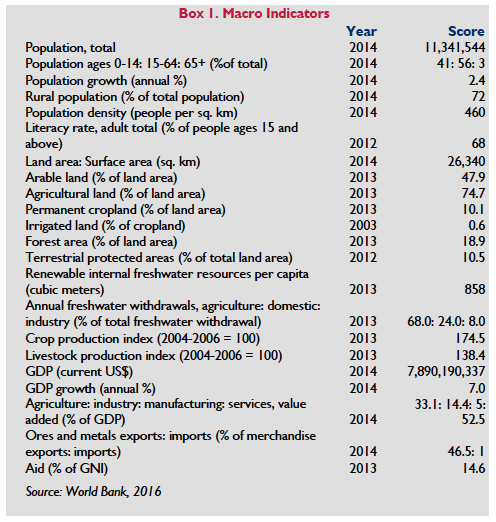

Rwanda is a small, landlocked, densely populated country with diverse terrain, an abundance of water resources. It is also one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots. The country has made numerous economic, policy and regulatory reforms promoting private sector growth, thus helping it to achieve macroeconomic stability and rapid average annual GDP growth of 8 percent from 2001to 2014. Since 2009, the percentage of Rwandans living under the poverty line has decreased from 56 to less than 30.

Access to agricultural land is severely limited and most farmers cultivate small, rain-fed plots. Seventy-five percent of Rwanda’s labor force works in agriculture, but only produced 33 percent of the GDP in 2014. Average landholdings are 0.3 hectares per household. In spite of formal laws supporting women’s rights and the equality of men and women, women’s decision-making authority and transfer rights over agricultural land remains restricted in practice. Finally, after the 1994 genocide and displacement of 30 percent of its population, Rwanda faced the additional challenge of resettling millions of refugees and internally displaced people on limited land for which there were often multiple claims.

In order to address its land scarcity and low productivity in agriculture, Rwanda instituted comprehensive land tenure reform and a systematic land registration program along with a Crop Intensification Programme. Participation in the program requires community agreement to land consolidation and resettlement. While the program has shown some early success, its continued application in hilly and marshy areas may prove more difficult. Climate change and climatic variability also pose challenges to the program.

Rwanda’s natural resources face growing pressures. Eighty-seven percent of Rwandans have reliable access to improved drinking water, which increased from 77 percent in 2005 (NISR). Rwanda is also at the center of the most biologically diverse region on the African continent. Finally, the country’s forest resources are threatened by the expansion of agricultural land and the extensive use of fuel-wood.

Rwanda’s small mineral sector is attracting increasing foreign investment and the government is supporting the integration of the country’s artisanal and small-scale miners into the formal sector.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

The government’s accomplishment of recording and registering rights to all land in Rwanda in a relatively short time frame is a demonstration of their commitment to improving tenure security. However, there is still work to be done to ensure full formalization and realize land tenure security for all:

- While there has been a robust implementation of the 2004 National Land Policy (NLP), and while the policy is viewed as a success, the manner in which the NLP has been implemented has been found to curtail some individual land rights. Key concerns relate to weaknesses preparing and implementing master plans for land use and development, expropriations in the public interest, relocation of rural dwellers to grouped settlements, the land use consolidation programs, confiscation of unused and abandoned properties, housing plot size restrictions, and restrictions on the use of other land types (among other concerns) (USAID 2015a). Donors should work with the government to identify strategies to reduce harms associated with land expropriation and resettlements.

- More work needs to be done to maintain formality through subsequent land transactions (after the first land registration). Preliminary evidence from the World Bank shows that as many as 60 percent of transactions in Rwanda are informal. Donors should support efforts to encourage formal land transfers and to examine options to create incentives for such formal transfers.

- Rwanda’s Land Information System lacks capacity, but could be linked with the Agricultural Land Information System currently under development with USAID support. The latter is designed to improve the agricultural investment climate.

- Local land use plans should be developed at the sector level, in a manner that is participatory and community-driven, so that they are based in the realities faced by farmers every day.

While Rwanda’s legal framework is impressive in its protection of women’s land rights, women still face challenges in securing their land, and control over it.

- Women in de facto unions are still vulnerable in the face of divorce or separation. Their rights to “marital” property should be protected, regardless of whether their marriage is de facto or formal. Donors could assist the government and civil society in continuing to build awareness of and support for women’s rights to marital property and clarify rights of women in informal consensual unions.

- Many men still hold the mindset that women should not receive land as inheritance or as an inter-vivos gift (or should at least not receive equal shares of land). It is necessary to shift the underlying norms and beliefs that keep parents from bequeathing land to their daughters. Donors could assist the government and civil society to build awareness of the benefits of providing women with more secure rights to inherit property or receive inter-vivos gifts.

- Some evidence has shown that women prefer to take their land-related disputes to local authorities rather than the Abunzi courts, because local authorities are seen to be more impartial. Donors could assist the government in training Abunzi members in gender equity principles, and in impartial decision making.

The government’s Crop Intensification Programme includes a land consolidation component. The component is supposed to be voluntary but consolidation is a condition of the program benefits. News reports suggest some communities have balked at consolidation and resettlement; in addition, a 2010 evaluation concludes that mechanized farming may not be feasible in hilly and mountainous areas, suggesting consolidation may not be appropriate in those (widespread) areas. Some farmers and observers have also expressed concern that while land consolidation and attendant mono-cropping could increase output and raise land productivity, most of the benefits may at least initially be realized by the wealthier farmers who can devote their land to cash crops. The poorer farmers who abandon traditional methods of managing risk and may have less reliable access to essential inputs and functioning markets may increase their vulnerability to food insecurity and the effects of environmental change. A USAID-funded study of land use consolidation found that has not fully eliminated the problem of food insecurity and that abundant food availability does not mean nutritional needs are being met. It is unclear which impacts can be attributed to LUC, and which are a direct result of agricultural investments provided by the state. Donors could support additional research to better understand which interventions are responsible for farmer’s agricultural productivity gains.

Rwanda has abundant water resources, and the government has made great strides in providing safe and clean water to its citizens. About 80 percent of disease is traced to the lack of adequate water treatment standards, facilities, and functioning infrastructure for water delivery. The government has targeted the sector for sustained support and is in the process of creating infrastructure for reliable urban water delivery that reaches informal settlements. In rural areas, government efforts are focused on local infrastructure development and rural water distribution and management, including creation of water user associations. In both urban and rural areas, the government has identified the need to include women in management of the water resources. Donors with experience in creating community-based resource management programs in sub-Saharan Africa could help the government create decentralized, community-based natural resource governance models. The models should include components designed to ensure active and effective community participation and benefit-sharing among all community members, including women and marginalized groups.

Summary

Rwanda is a small country with diverse terrain and an abundance of water resources. It is also one of world’s biodiversity hotspots. High population density and a hilly terrain punctuated by steep slopes and marshland combine to limit access to agricultural land in this small country.  A history of civil war and genocide contributed to increasing pressures on land and the environment. For example, Rwanda has experienced the most dramatic refugee returns in Africa. In 1994, an estimated one million people (more than 10 percent of the population) were massacred. Thirty percent of the population temporarily fled the country, joining the diaspora that had occurred 30 years earlier. Within a period of three years, Rwanda was faced with the need to resettle millions of refugees and internally displaced people on limited land for which there were often multiple claims of rights.

A history of civil war and genocide contributed to increasing pressures on land and the environment. For example, Rwanda has experienced the most dramatic refugee returns in Africa. In 1994, an estimated one million people (more than 10 percent of the population) were massacred. Thirty percent of the population temporarily fled the country, joining the diaspora that had occurred 30 years earlier. Within a period of three years, Rwanda was faced with the need to resettle millions of refugees and internally displaced people on limited land for which there were often multiple claims of rights.

The majority of Rwandans rely on agriculture for their livelihoods, and despite the country’s economic growth in recent years, most farmers cultivate small, rain-fed plots on a subsistence basis. The waves of population movement created uncertainty and tenure insecurity, exacerbating already challenging cultivation conditions.

The Rwandan government was keenly aware of the importance of land access and secure tenure to the peaceful reintegration of returnees, demobilized soldiers, and former prisoners. Particular groups, such as women-headed households and genocide survivors, required proactive efforts to ensure their rights are protected. Rwanda’s Land Tenure Reform Programme initiated a systematic land registration effort designed to promote land access and address tenure insecurity. As of 2013, the program had demarcated and adjudicated 10.3 million parcels, of which 81 percent had received approval for titling. The government has also undertaken a Crop Intensification Programme in an attempt to improve agricultural productivity. The program is conditioned on community agreement to land consolidation and resettlement and mandates crop selection based on region. The program’s land use consolidation component has shown some early success in reducing food insecurity, improving yields and contributing to poverty reduction (Gillingham and Buckle 2014; Musahara et al 2013). At the same time, some farmers have expressed concern that these benefits may be concentrated in the hands of wealthier farmers.

Rwanda has made significant strides in ensuring that its population has access to safe drinking water. The government adopted a new water policy in 2004 that identified a number of significant challenges in the sector, and has undertaken several projects targeting those challenges, including constructing infrastructure for water delivery in rural and urban areas, supporting rainwater harvesting, and investing in irrigation.

Rwanda is located at the center of the Albertine Rift, the most biologically diverse region on the African continent. The country has significant forest resources, threatened by the expansion of agricultural land. The population is highly dependent on fuelwood for heating and cooking. These pressures impact highly valuable and biodiverse lands.

Mining is the country’s second largest export; it generated US $210.6 million of foreign exchange in 2014. The country privatized the sector in 2007-2008, and adopted a new mining law and policy in 2008-2009. Foreign investment in the sector has been increasing, and the government is supporting the integration of the country’s artisanal and small scale miners into the formal sector (Rwanda Development Board).

Women constitute 54 percent of the Rwandan population, head approximately 20 percent of households, and are strongly represented in the parliament and government, at both the national and local level. Many formal laws drafted in recent years contain express statements of equality of women and men and support for women’s rights to natural resources and participation in governance bodies. However, in practice and especially in rural areas, paternalistic principles limit women’s rights to access and control agricultural land.

Land

LAND USE

Rwanda is a small, landlocked country in the Great Lakes region of Central Africa. The country has a land area of 24.7 thousand km², with an average altitude of 1,250 meters. The country’s terrain rises from lowland plains and swamps in the east to central uplands and rolling hills that meet a range of mountains crossing the country from the northwest to southeast. The divide separating the Congo and Nile drainage system has an average elevation of 2,700 meters and slopes sharply to the west to meet Lake Kivu and the Ruzizi River Valley. Seventy-five percent of Rwanda’s land is classified as agricultural; 10 percent of total land is permanent cropland, of which only 0.6 percent is irrigated. Six percent of the land is marshland and about 19 percent of total land is classified as forest. Slightly more than 10 percent of the total land area is in protected areas (World Bank 2009a; FAO 2009; USDOS 2010).

Rwanda has one of the fastest growing populations in Africa, and with a 2014 population of 11.3 million people, is one of the most densely populated countries on the continent. In 2014, 72 percent of the population lived in rural areas, although the percentage of urban residents is growing: between 2010 and 2015 the country’s average urban population growth rate was 6.4 percent (UNDP 2016).

Rwanda’s 2014 GDP was nearly US $7.9 billion, of which the agricultural sector made up 33 percent, industry 14 percent, and services 52 percent. The percentage of Rwandans living in poverty has dropped from 44.9 percent in 2011 to 39.1 percent in 2014, but one in four households still live in extreme poverty. Poverty is concentrated in rural areas where 85 percent of the population lives; in rural areas 49 percent of the population lives in poverty (compared to 22 percent in urban areas). Income rates remain unequal; in 2013 the income Gini coefficient was 50.8. In rural areas, agricultural entrepreneurs are benefiting from investments in agriculture while the majority of Rwandan peasants face increasingly difficult living conditions (REMA 2009a; UN-Habitat 2010; World Bank 2009a; UN-Habitat 2009; Ansoms 2009; WBDI; UNDP 2016; IFAD 2014).

Most rural households are smallholder subsistence farmers growing beans, maize, Irish potatoes, and sweet potatoes in higher altitudes and sorghum, banana, cassava, and beans at lower altitudes. Most cultivation is on rain-fed land; less than 1 percent of cropland is irrigated. Most smallholders keep livestock, primarily for manure, although livestock is also used for meat and dairy products. Some smallholders cultivate cash crops on all or a portion of their land. Primary cash crops include tea, coffee, and banana; cultivation of crops for export is increasing. Some commercial enterprises, such as the tea industry, engage local farmers through out-grower schemes. Local farmers also form cooperatives that purchase and cultivate tea bushes on state land (FAO 2009; GOR 2007; REMA 2009a). Farmers also form cooperatives to collect, wash and sell coffee, including specialty Arabica Bourbon coffee.

Agricultural productivity is, however, constrained by geography, soil degradation and erosion, and limited use of inputs. Crop residues, which are left on the fields, help the soil retain moisture and replenish nutrients and are collected and used for fuel in many areas. The pressure on land has pushed cultivation into marginal land and unstable areas. Expansion of cultivation into higher altitudes has contributed to soil erosion, which affects half the country’s land (FAO 2009; Wong et al. 2005; Musahara 2006; World Bank 2009a).

Agricultural productivity is, however, constrained by geography, soil degradation and erosion, and limited use of inputs. Crop residues, which are left on the fields, help the soil retain moisture and replenish nutrients and are collected and used for fuel in many areas. The pressure on land has pushed cultivation into marginal land and unstable areas. Expansion of cultivation into higher altitudes has contributed to soil erosion, which affects half the country’s land (FAO 2009; Wong et al. 2005; Musahara 2006; World Bank 2009a).

In the late 1990s, Rwanda experienced a 17 percent urban growth rate and the number of informal settlements rose. Eighty-three percent of Kigali’s population lives in informal settlements, which occupy 62 percent of the area of the city. In 2001, seventy-two percent of residents of Kigali’s informal settlements were not formally employed, and nearly 90 percent of the homes were constructed of cardboard, plywood, and other substandard materials. Kigali is expected to grow as rapidly as 6 percent a year in coming years, and conditions in informal settlements have been improving in many areas. For example, in the period from 2000-2010, an estimated 20 percent of residents have moved from slum conditions. The urban population is expected to continue to rise to nearly 30 percent by 2030 (UN- Habitat 2010; UN-Habitat 2009; GOR Urban Housing Policy 2008; World Bank 2012).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

With a total land area slightly smaller than the state of Maryland and a population of more than 11 million people, Rwanda has one of the highest population densities in the world (averaging 460 inhabitants/km²). Most Rwandans are members of one of three ethnic groups (Hutu, Tutsi, and Abatwa), but in an effort to support post-genocide unification, the government does not collect information on ethnicity. Many women were widowed during the war and there was a steep rise in the number of women-headed households, many of which had to care for orphaned children of family members. Other marginalized groups include the abasigajwe inyuma n’amateka (known as the Abatwa or Twa), genocide survivors, orphans, and legally vulnerable women (e.g., polygamous wives). Many of those in marginalized groups are landless and without means of income generation. While firm figures are not available, some reports estimate that upwards of 90 percent of the Twa in Rwanda are landless (GOR 2007; Musahara 2006; André and Platteau 2005).

Almost 75 percent of the country’s land is used for agriculture, with 1.6 million hectares under cultivation and 0.47 million hectares of permanent pasture. The country has 165,000 hectares of marshland, of which about 57 percent is cultivated. The trend in recent decades has been the expansion of cultivated land and loss of fallow, pasture, forestland, and woodlots (REMA 2009a)

As in many countries, rural land distribution is skewed. The smallest group (about 24 percent of all households) controls roughly 70 percent of the country’s agricultural land, with average landholding of about two hectares. Many of the landholders in this category are urban elites and many of the holdings are in excess of 20 hectares. The second smallest group (30 percent of households) controls 25 percent of agricultural land and has average landholdings of 0.6 hectares. The largest group (36 percent of households) controls only 6 percent of the country’s agricultural land. Households in this category have average holdings of 0.11 hectares. This group includes the 11 percent of all households that are landless. Most landless households are poor and marginalized persons, although the figure includes purely urban dwellers without rural land (GOR 2007; IMF 2013).

The average household’s landholding is divided among 4-5 small plots of land, often in different locations that may be some distance apart. Farmers in some areas report valuing the flexibility in holding several plots because they can diversify their production in the different locations and have some protection against environmental damage and shocks that may impact plots in one area but not others. However, land legislation and agricultural sector policy supports the consolidation of land: the 2013 Land Law provides that agricultural plots cannot be subdivided if the resulting parcels are less than one hectare, and parcels held by a single landholder must be consolidated under one title in the registration process. Participation in the Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources (MINAGRI)’s Crop Intensification Programme requires farmers to consolidate land holdings and communities wishing to participate must voluntarily agree to such consolidation and to resettlement (GOR 2007; IFDC 2010; GOR Organic Land Law 2005).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution of the Republic of Rwanda recognizes state and private property and grants every citizen the right to private property, whether held individually or in association with others. The state has the authority to grant rights to land, including private ownership rights, and to establish laws governing land acquisition, transfer, and use. State land is classified as public or private; public land cannot be alienated. Customary land (and collective customary land) is no longer recognized in Rwanda, which makes it unique among sub-Saharan African countries. Instead, land is held by individuals and families (GOR Constitution 2003).

The National Land Policy of 2004 provides that: (1) all Rwandans will enjoy the same rights of access to land; (2) all land shall be registered and land shall be alienable; (3) consolidation of household plots is encouraged; and (4) land administration shall be based on a title deeds registration system (GOR Land Policy 2004). This land policy was originally planned to be revisited in 2014 (after 10 years of implementation) and while it is widely viewed as successful, there are concerns related to how the Policy has been implemented and how it impacts individual land rights, including rights of women in informal marriages or consensual unions (USAID 2015a).

In 2013 Rwanda transformed the 2005 Organic Land Law (Organic Law Determining the Use and Management of Land in Rwanda) into ordinary law to comply with the Constitution, and also addressed particular weaknesses of the 2005 law. The Law N° 43/2013 of 16/06/2013 (Law Governing Land in Rwanda) was gazetted in June 2013. This law provides that land is the common heritage of past, present, and future Rwandans. The State has supreme power of management over all land in Rwanda, and it is required to manage the land for the general interest of all, and for economic and social development.

The Land Law recognizes rights to land obtained under customary law as equivalent to rights obtained under formal law, requires land registration, and sets minimum plot sizes for agricultural land (GOR Land Law 2013a).

At least one order has been passed to clarify and implement various aspects of the Land Law: the Ministerial Order of 2013 regarding modalities of land sharing. This order stipulates that land shared must be large enough so that each party receives land that is at least one hectare, however, this requirement may be challenging to implement as customary inheritance practices and gifts of land made during the lifetime of a landholder may lead to fragmentation into smaller parcels (GOR 2013 Ministerial Order).

TENURE TYPES

The Land Law classifies land as either individual land or state land. Individual (i.e., private) land can be obtained under principles of customary law or under formal law. State land includes: (1) state land in the public domain (e.g., lake shores, national parks, roads, tourist sites), which generally cannot be alienated; (2) state land in the private domain of the state (e.g., vacant land, swamps, plantations, expropriated land), which can be alienated; and (3) district, town, and municipality land, which is controlled by local governments (GOR Land Law 2013a).

The formal law recognizes the following tenure types, some of which were issued under prior land laws yet continue in effect:

- Right to Emphyteutic Lease. According to the land law, every person possessing land acquired through customary means or purchase is the recognized proprietor. The formal law recognizes individual rights to land through the right to Emphyteutic lease.

- Freehold Right to Land. These rights apply to developed land with infrastructure, reserved for residential, industrial, commercial, social, cultural or scientific services.

- Public Land. Public land is in the domain of the state, and includes land belonging to public institutions and or local authorities.

Other tenure types delineated in the 2013 Land Law include: (1) State Land in Public Domain, (2) Land in Public Domain of Local Government, (3) State Land in the Private Domain, (4) Land in the Private Domain of Local Authorities, and (5) Public Institutions Land. The vast majority of land in Rwanda was titled during the land regularization program (Musahara 2006; GOR 2007; GOR 2010c).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Most rural land in Rwanda is accessed through inheritance and leasing, and most urban land is accessed through purchase and leasing. Other methods of obtaining land include via government land allocations, borrowing, gift, first clearance, and informal occupation (GOR 2007; GOR Land Registration Order 2008; GOR et al. 2008).

At various times since the end of the genocide, the Rwandan government has allocated land to returning refugees and displaced people in an effort to provide people with land for farming and to prevent further conflict. Beginning in 1994, refugees (some of whom left the country in the 1950’s and 1960’s) returned to the country and sought to reclaim land, which may have been occupied by others for years, if not decades. In order to accommodate returning refugees, the government allocated land in game reserves and parks and created resettlement villages (umudugudu) in some areas. The government also instituted programs for land sharing in some areas, which required existing occupants to give up a portion of their land to returnees. More recently this policy was focused on breaking up large tracks of land acquired by elites in the Eastern Province. The compulsory villagization and land-sharing programs were often conducted without due process or payment of fair compensation, required settlement in areas without services or adequate farmland, and resulted in increased insecurity and tension (GOR 2007; Bruce 2007).

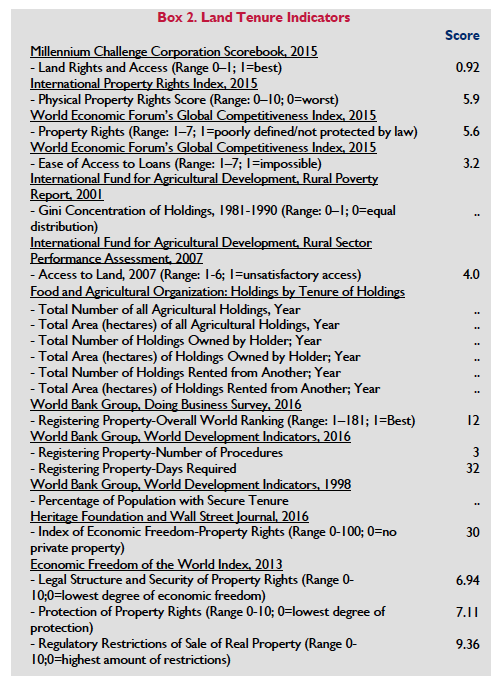

In an effort to address continuing insecurity regarding land rights, the 2005 Organic Land Law and its implementing decrees required registration of all land. By 2007 (prior to the initiation of countrywide systematic registration), rights to about 80,000 parcels held under titre proprietre, contrats de cession gratuite, acte de notoriete, and paysannat land were registered. Most registered land were urban parcels, large commercial landholdings, and land held by churches. As part of its National Land Tenure Reform Programme, in 2010 the government began the process of transferring rights registered under previous laws and demarcating and registering unregistered land under a systematic registration plan. The systematic registration took place in all 30 districts, and by August 2013, 10.3 million parcels were demarcated and adjudicated. Of those, 81 percent were granted title (GOR 2007; GOR et al. 2008; GOR 2010c; Gillingham and Buckle 2014).

Registration of property (for example, in the case of transactions) requires three steps: (1) title search at the district land registry (2) notarization of sale; and (3) finalization of registration at the district land registry and obtaining new dead. The process takes an average of 32 days and costs RWF 27,000 (a fixed fee) (World Bank 2016; GOR 2007; GOR et al. 2008). Joint ownership of land by married couples and joint registration of marital property is presumed by the new Land Law, and the Family Code (GOR Organic Land Law 2005; GOR Order on Lease Procedures 2008).

As noted, customary land tenure is not recognized by the state, and so land that is informally transferred or transacted according to old (but now unrecognized) customary rules is insecure. While land tenure regularization formalized customary rights, people continue to conduct informal transfers based on this old customary tenure system. Prior to regularization, initial surveys conducted while the National Land Reform Programme was being developed reported that most landholders were highly motivated to formalize their rights under the new legal framework. Now, a majority of Rwandans are familiar the benefits of formalization and so it is expected that informal transfers will diminish (GOR 2007; GOR et al. 2008; Biraro et al. 2015).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Rwanda’s 2003 Constitution states that women and men have equal rights and prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex. The 2013 Land Law, which in its English translation grants husbands and wives equal rights to land, has been interpreted as consistent with the Constitution: women and men have equal rights to property. Thus under formal law, women have the ability to purchase and hold property on their own (GOR Constitution 2003; GOR Organic Land Law 2005; Scalise and Giovarelli 2010).

The Constitution recognizes only monogamous marriages between a man and woman that have been registered according to the civil law. Law No. 22/99 (Law to Supplement Book One of the Civil Code and to Institute Part Five regarding Matrimonial Regimes, Liberalities and Successions) governs marital property and inheritance rights.

The Constitution recognizes only monogamous marriages between a man and woman that have been registered according to the civil law. Law No. 22/99 (Law to Supplement Book One of the Civil Code and to Institute Part Five regarding Matrimonial Regimes, Liberalities and Successions) governs marital property and inheritance rights.

Echoing the Constitution, Law 22/99 only recognizes martial property rights arising out of formal, civil marriages; consensual unions and polygamous marriages are not recognized (though the 2008 Gender Based Violence law does protect some marital property rights of women living in de facto unions).

Under Law 22/99 couples in registered marriages can elect one of three marital property regimes: (1) a community property regime in which property is held jointly; (2) a limited regime in which the couple designates property acquired during marriage as either community or separate property; or (3) a separate property regime. The selected regime governs the couples’ rights to property in the event of death, divorce, or separation. If, for example, a couple in a community property regime divorces, each spouse will be entitled to one-half of the property. If the couple does not make an election, a community property regime is presumed. The community property regime is the most commonly elected (GOR Law 22/99 1999; Brown and Uvuza 2006; GOR Gender Based Violence Law).

Law No. 22/99 includes some additional protections for land. In the event of a husband’s death, the law provides the widow with usufructuary rights to the marital house, regardless of the property regime selected. The law also states that the written consent of both spouses is required for land transactions (GOR Law 22/99 1999; Brown and Uvuza 2006).

Law No. 22/99 of 12/11/1999 (Law to supplement book one of the civil code and to institute part five regarding matrimonial regimes, liberalities and successions) also governs inheritance rights and provides that children have the right to inherit their parents’ property equally and without regard to gender. It also provides them the right to ascending partition, regardless of sex (though children are not guaranteed rights to equal shares). If land cannot be partitioned because it would violate the one-hectare minimum holding requirement under the 2013 Land Law, an heir can be compensated with the monetary value of their land share. The laws do not direct how landowners shall compensate all interests in the event that the land cannot be partitioned (GOR Law 22/99 1999; Organic Land Law 2005; GOR 2007). Taken as a whole, Rwanda’s legal framework protects women’s rights to land and property and knowledge of men and women’s equal rights to land is widespread.

Yet, despite the constitutional mandates of equality and provisions in the formal laws supporting women’s land rights, women still face some barriers in securing their rights to land. For example, women in informal marriages and consensual unions cannot typically claim their rights to land in the case of a separation, and the general understanding is that women in these situations do not have the same rights to land as men. Women’s rights to inheritance and inter-vivos gifts in these conditions are also less certain than men’s. For example, in a 2015 study, when asked how the land of a deceased couple married under the community property regime should be shared between a son and daughter, 71.3 percent of respondents said that the land would be equally divided between the son and daughter indicating good understanding of formal rules. Shifting social norms related to informal unions may take time and while formally married women’s rights are widely recognized, the mindsets of men and boys are still evolving when it comes to women’s land rights more broadly. For example, women often feel pressure to relinquish their rights to their brothers, especially if they move to their husbands’ villages (Scalise and Giovarelli 2010; Brown and Uvuza 2006; GOR 2007; GOR Law 22/99 1999; Jones-Casey 2014; Ishingiro 2015).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

As of December 2009, the Ministry of Natural Resources has primary responsibility for land matters. The Ministry is responsible for addressing issues in policy, in particular through Ministerial orders and/or instructions that set out laws and procedures for the administration, planning and allocation of land (Ministry of Natural Resources; Rwanda Natural Resources Authority).

The Rwanda Natural Resources Authority (RNRA) is in charge of land registration and land use planning. The Lands and Mapping Department within the RNRA was created to implement the National Land Tenure Reform Program (put in place by the National Land Policy and the Organic Law Determining the Use and Management of Land in Rwanda). The Lands and Mapping Department works to improve land tenure security through an efficient, transparent, and equitable system of land administration (RNRA).

Rwanda’s Ministry of Natural Resources is responsible for ensuring the sustainable management of natural resources in the country. It is governed by several national policies and strategies, including Vision 2020, National Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy, Green Growth and Climate Resilience Policy, the Government Agenda, National Investment Strategy, Good Governance and Decentralization (among others). Specifically, the Ministry focuses on sustainable land management, sustainable integrated water resources management, sustainable management of forest and biomass resources, ecosystem conservation and improved functioning, sustainable mining and mineral exploitation, environmental sustainability, and policy, legal and regulatory frameworks for environmental and natural resource management (MINIRENA).

The Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources (MINAGRI) is responsible for initiating and managing programs designed to transform and modernize the sector to ensure food security and to contribute to the national economy. The Ministry’s priority programs target: intensification and development of sustainable production systems, support for professional development of producers, promotion of product chains and agro-industry development, and institutional development (GOR 2010c; GOR 2010d).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Rwanda’s land reforms, and the land registration process in particular, do seem to have contributed to a more active land market. One study showed that half of a sample of 120 respondents made a land transaction between 2011 and 2015. A 2014 study of land market values and urban land policies in Rwanda found that in urban areas there are very high rates of property ownership (estimated at 69 percent), and more than two-thirds of formally owned properties have been acquired through direct market transactions. However, there is some evidence that some people in urban areas continue to transfer land using informal processes. For example, a 2012 case study of Butare Town found that half of all respondents acquired land through informal purchase (Niyonsenga et al 2015; USAID 2014a).

Prior to the start of systematic land registration and revision to land registration procedures, the cost of land registration and lack of familiarity with the requirements limited the number of registered transactions. These constraints continue to impact decisions to transfer land informally in rural areas.

Most people prefer to retain ownership and lease their land if they are unable to use it, but sales do occur. The most common reasons for land sales are the need for cash for livelihood purposes such as debt repayment and medical costs (i.e. distress sales), raising money for investment in businesses, and relocation. Land purchasers buy land to increase their landholdings and to access more fertile land or land suitable for livestock.

The land lease market is active in rural and urban areas. Farmers lease land on a seasonal or annual basis in order to gain access to land in various areas for growing a diversity of crops or to use better soil.

Some people, such as younger couples and women, lease land because they cannot afford to purchase land. Some households form groups and lease grazing land for their livestock. In rural areas, landholders often lease out land that they are unable to farm themselves because of disability, age, or non-agricultural commitments. The state leases marshland, which farmers cultivate on a seasonal basis.

Leases are commonly cash transactions, although there is some sharecropping in some areas. In urban areas, leasing is the most common means by which people access plots (GOR 2007).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Article 29 of the Constitution provides that the state may expropriate private property in the public interest consistent with circumstances and procedures defined by law and subject to payment of prior and fair compensation. The 2015 Expropriation Law (Law No. 32/15 of 11/06/2015 Relating to Expropriation in the Public Interest) defines public interest to include construction of infrastructure such as roads, railway lines, airports, dams, schools, and oil pipelines. It also covers exploitation of minerals and natural resources in the public domain and activities associated with implementing land use and development plans. The expropriation process is conducted at the district or municipal level (for the City of Kigali) or by the relevant Ministry and it requires that the committee managing the process conduct consultative meetings with those people affected by the expropriation. Committees are required to broadcast decisions over at least one radio station and in at least one Rwanda-based newspaper. Just compensation is based on the prevailing market rate for the land – which is established by the Institute of Real Property Valuers – and on activities carried out on land along with the value of any disruption caused by the expropriation. Compensation may be paid in monetary form or another agreed upon form. If the landholder is married, compensation is paid into an agreed upon account and withdrawal of funds requires the written authorization of the co-holder/s. Parties affected by expropriation do have a right of review (GOR Constitution 2003; GOR Expropriation Law 2015).

Land expropriation has been relatively common in Rwanda. For example, historically the government has used its power to take land to try to address the needs of returning refugees in the years following the genocide. More recently, expropriation has been used to expand urban areas (particularly the City of Kigali), and build the country’s infrastructure. In addition, market-led expropriations are common. In some cases, investors and developers approach the government with a development plan, and the government expropriates the desired land. In other cases, developers seeking land approach landowners directly and with the support of local government pressure landholders to leave the area in exchange for compensation. The processes for determining compensation are often not transparent or tied to fair market values and poorer landholders are often susceptible to the pressure and offer of cash (GOR 2007; USDOS 2009; Bruce 2007; Musahara 2006, USAID 2014c).

Research on the impacts of expropriation (under the 2007 expropriation law) shows that the most important expropriation-related issues were insufficient and delayed compensation. The same study found that delayed compensation and insufficient compensation have measurable negative impacts on individuals whose land was expropriated (USAID 2015b).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Land disputes are common in Rwanda. The pressure on land combined with limited non-agricultural livelihood options was identified as a factor that contributed to the 1994 genocide. The violence, which caused large groups of people to move in and out of the country and in and out of rural areas, put additional pressure on the land as multiple groups occupied and laid claim to the same land over time. In 2001, the government estimated that as many as 80 percent of the cases coming before prefect courts were land-related disputes. However, a 2015 household survey of 1,975 households found that only 4.11 percent of parcels were in dispute (Musahara 2006; André and Platteau 2005; GOR 2007; Wyss 2006; USAID 2015c).

The reintegration of demobilized soldiers, former prisoners, and old- and new-case returnees from neighboring countries has also resulted in competing claims to land. However, the most common causes of land disputes currently relate to inheritance claims, boundary encroachment, claims arising from polygamous relationships, and land transactions (USAID 2015c). The overwhelming majority of disputes are occurring within extended families rather than between different social groups (GOR 2007; Wyss 2006; ARD 2008a; ARD 2008b).

Most land disputes are initially handled through informal procedures using customary forums such as: the family council (a customary institution whose make-up changes depending on the issue in question); leaders of the nyumba kumi (a defunct administrative level for up to 10 households, whose leaders still retain some authority); umudugudu leaders (elected village level leaders); and the cell executive committee. (ARD 2008a). The formal court system includes courts at the town, municipal, district, and provincial levels. Appeals are heard by the High Court and Supreme Court. After the genocide, Rwanda instituted a mandatory mediation process for all cases with a monetary value of less than RwF three million (about US$ 5,000). The jurisdiction of the mediators, known as abunzi, extends to civil cases relating to land rights and land-related inheritance disputes. Each cell has a group of 12 abunzi, 30 percent of whom must be women, and who hold the position for two years. Cases are heard by a panel of three abunzi, who are required to settle the dispute within 30 days. The decisions of the abunzi are enforced by local authorities, and parties can appeal to the court of first instance. The abunzi are not compensated, and receive little training on conflict resolution skills or the law. Their strength of their authority is debated. Recent research suggests that women may prefer to have their cases heard by local authorities, because they are perceived to be less biased. There is no requirement that parties present cases to the local authorities before proceeding before the abunzi (ARD 2008b; Musiime 2007; Bruce 2007; GOR 2007; Takeuchi and Marara 2011; Jones-Casey et al 2014).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The government of Rwanda’s ambitious National Land Tenure Reform Programme, was completed in 2013. Between February 2010 and August 2013, 10.3 million parcels were demarcated and adjudicated. Of those 81 percent were granted title. The process involved demarcation of land, adjudication and recording, issuing claims, recording objections and disputes, publishing records, mediation, final registration and title issuance (Gillingham and Buckle 2014).

In 2008, the Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources (MINAGRI) introduced its Crop Intensification Programme (CIP). The program is designed to increase agricultural productivity through land consolidation, purchase and distribution of bulk fertilizer and seeds through the private sector (enterprises or farmers’ cooperatives, using auction and vouchers), extension services, and creation of credit linkages for farmers. Working through local government, the program identifies suitable land. In planned villages, the land use design separates residential land from agricultural land. In other areas, farmers who wish to participate in the program must agree to resettle to residential areas so that agricultural land can be consolidated to better allow for mechanized farming techniques. Between 2008 and 2012 the area under cultivation under the Land Use Consolidation program has increased from more than 28,000 hectares to more than 602,000 hectares. MINAGRI has continued to develop its crop list, most recently suggesting that eastern provinces will plant coffee, rice, corn, bananas and pineapples; the southern provinces will focus on manioc roots, wheat, tea and coffee; the western provinces will grow tea, coffee, potatoes; the Northern provinces will produce potatoes, wheat, pyrethrum and maracuja; and Kigali city will produce flowers and fruits (IFDC 2010; Ntambara 2010; Twizeyimana 2010; Ansoms 2009; Ansoms et al. 2010).

Recent research on the impacts of the Land Use Consolidation (LUC) concludes that most (but not all) farmers are satisfied with the program, and believe that it has brought them benefits, including increased crop yields. By participating in LUC, farmers gain access to inputs and extension services. However, despite the overall positive picture, food security, poverty and vulnerability to shocks are still high. And farmers feel pressure to participate in the program, despite the fact that it is voluntary (USAID 2014a).

In urban areas, Rwanda’s National Urban Housing Policy, which was adopted in 2008, provides for the upgrading of informal settlements. The policy provides that upgrading will not presume destruction of neighborhoods but will proceed with a rational program to bring settlements into compliance with standards for access, services, buildings, and sanitation. If rebuilding is required, the state will assist the residents with alternative accommodation and facilities. Public protests against slum clearance have grown in recent years, and efforts are underway to develop technical experience in upgrading existing settlements (GOR Urban Housing Policy 2008; Kalimba and de Langen 2007).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

USAID’s LAND Project (2012-2016) supported Rwanda’s long-term sustainability by strengthening the resilience of its citizens, communities and institutions to adapt to land-related economic, environmental and social changes. The project was funded at US$ 11,970,000. USAID’s Promoting Peace through Land Dispute Management (2013-2016), aimed to manage and mitigate land-related conflict by improving the capacity of local institutions in addressing land disputes.

The World Bank has an ongoing Land Governance Assessment Frameworks program in ten countries, including Rwanda. The LGAF is a diagnostic tool used to identify needs in land governance and prioritize reforms for addressing them.

DFID funds ongoing land registration programs in partnership with the Rwanda Natural Resources Authority, specifically supporting the Government of Rwanda to build on and ensure sustainable maintenance of the land register and improve the capacity of land institutions and delivery services (DevTracker). DFID also funded the large (~US$ 37,000,000) Land Tenure Regularisation Programme.

The European Commission supports a basket-funded implementation of Rwanda’s government strategy for land reform (European Union). Sweden is funding the Strengthening Proximity Justice in Rwanda project (2015-2018), to enable citizen participation in proximity justice.

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Rwanda has abundant water resources, including 101 lakes covering almost 150,000 hectares, 6,400 kms of rivers, and 860 marshlands spanning an estimated 278,000 hectares. Lake Kivu, one of Africa’s Great Lakes, lies on the western border with the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Akagera (Kagera) River is a remote source of the Nile River and the largest river flowing into Lake Victoria. It has the potential to provide an inland transportation route for the passage of goods. Rwanda’s marshlands are productive ecosystems, responsible for cycling nutrients, recharging groundwater, and helping mitigate flooding. The marshlands provide habitat for wildlife and fish, and support seasonal cultivation (FAO 2009; REMA 2009a; GOR Water Policy 2004).

Rwanda has two major drainage basins: The Upper Nile basin (67 percent of the country) and the Congo basin (33 percent). The country’s annual rainfall varies from 700 mm to 1400 mm in the east and western lowlands, between 1200-1400 mm in the central regions, and from 1300-2000 mm in the high altitude region. Groundwater has been relatively unexplored, although its potential for normal recharge is potentially compromised by the extent of soil erosion. In 2000, water withdrawals were estimated at 0.2 billion cubic meters per year. Agricultural use accounts for 68 percent of water withdrawal, while domestic use and industry account for 24 percent and 8 percent respectively (REMA 2009; FAO 2005; FAO 2009; World Bank 2009a; GOR Water Policy 2004; WBDI 2015).

Rwanda has made significant strides in ensuring access to clean drinking water. According to the National Institute of Statistical Research, the proportion of households using drinking water from improved sources increased from 74 percent to 85 percent from 2010/11 to 2013/14. In urban areas the numbers were higher (90 percent), compared to rural areas (83.7 percent). However, in urban areas the population growth is outpacing service development and delivery. A 2013 study found that only 56.3 percent of households in two informal settlements of Kigali had improved sanitation systems. Other studies found that access to safe drinking water in informal settlements is one third the amount available in other parts of the city (AfDB 2009; UN-Habitat 2009; Tsinda et al 2013).

Rwanda’s water resources are also threatened by contamination from untreated waste and poor drainage, especially in urban and peri-urban areas. Eighty percent of diseases suffered by the population are attributed to contaminated water and poor sanitation. Water resources are also threatened by sedimentation, discharge from industry, and invasive species such as the water hyacinth that choke some lakes and waterways (FAO 2005; REMA 2009a).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Rwanda’s Water Law (Law No 62/2008 of 10/09/08 Putting in Place the Use, Conservation, Protection and Management of Water Resources Regulations) was designed within the framework of the 2004 Water Policy. The 2008 Water Law provides that water is a public good and responsibility for its proper use and protection is the responsibility of the state, the private sector, civil society, and the citizens. This law recognizes principles such as: protecting water resources from pollution, requiring water users and water polluters to pay, using water user associations, and providing for the public distribution of water. The priorities for water distribution are: (1) the population; (2) livestock; and (3) hydroelectric energy production (GOR Water Law 2008).

In 2011 the government replaced its previous 2004 Water Policy with a new National Policy for Water Resources Management (GOR Waters Resources Policy 2011). The Policy sees water as a key, finite resources required for the sustainable socio-economic development of the country that must be carefully use and managed to ensure maximum benefits and to minimize harms. It also identifies the right to water as a human right. The Policy identifies key challenges including: (1) uncertainty related to climate; (2) competition and conflict over water resources; (3) poor land use practices including deforestation and conversion of wetlands; (4) limited infrastructure and limited supply of safe water; (5) limited financial, technical, and administrative capacity to effectively manage water resources; (6) limited functional framework to support decentralized water users and managers and (7) limited data on water resources (GOR Water Resources Policy 2011). The Policy emphasizes the importance of integrated and participatory water management to address these challenges. It also places an emphasis on improved monitoring and capacity building.

In 2010 Rwanda updated the National Policy and Strategy for Water Supply and Sanitation Services after an extensive stakeholder consultation process. The policy responds to the institutional reforms that took place after the 2004 Water Policy was adopted, including the decentralization of responsibilities for rural water and sanitation private sector engagement

The 2013 Land Law provides that the country’s lakes, rivers, and groundwater are in the public domain and the use of water resources is shared by all (GOR Organic Land Law 2005; Law Governing Land 2013).

TENURE ISSUES

Water is considered a common resource that belongs to everyone and is, therefore, owned by no one. Land owners are required to use water resources in a manner that is rational and optimizes the use of the resource. No one can divert the course of a river or water body without permission, and no one is supposed to pollute water resources or water bodies. Rights to water are considered temporary only; water rights are not alienable, cannot be seized, and cannot be acquired by prescription (GOR Water Law 2008; GOR Organic Land Law 2005; Law Governing Land 2013).

The state has responsibility to manage water resources in the public interest. The state can enter into agreements with third parties for the management of the country’s water resources. Those holding land rights must grant easements for the construction of piping of water for rational use and distribution (GOR Water Law 2008; GOR Organic Land Law 2005).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Responsibility for water resources and distribution of water in Rwanda is divided among several agencies. The Ministry of Infrastructure (MININFRA) is responsible for developing institutional and legal frameworks, national policies, strategies and master plans relation to water supply and the sanitation subsector. The Ministry of Natural Resources, through its Department of Integrated Water Resources, works to ensure the protection, conservation, restoration and rational use of water resources to meet the country’s medium and long-term socio-economic development goals. The Ministry of Natural Resources is responsible for helping to set water resources policy; ensuring compliance with relevant legislation; representing the government in intergovernmental organizations on matters related to water. The Department of Health (MINISANTE) develops policy and promotes hygiene and household sanitation. District-level basin committees are responsible for preparing district-level water management plans. The district basin committees have the power to delegate authority for management of water resources and water infrastructure to local water user associations. The Department of Integrated Water Resources is in charge of implementing water resources management policy, strategies and laws (GOR Water Law 2008; REMA 2009a; RWASCO 2010; MINIRENA Water Resources).

The first meeting of the National Water Consultative Commission was held on October 30th, 2014. The commission will contribute to the implementation of integrated water resource management in the country (RNRA 2014).

As of 2014, water is provided by the Water and Sanitation Corporation (WASAC) which provides water and sewage services. WASAC is a national utility and was previously known as Electrogaz (and before that REGIDESCO). In 1999, the Government removed the utility’s monopoly on electricity and water supply. This led to a new organizational structure and today WASAC is separate entity from the electricity corporation (WASAC, n.d.)

The Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources (MINAGRI) is responsible for the rational use of water potential for agricultural purpose including irrigation development and livestock development. MINAGRI, through the Unit of Agricultural Engineering and Soil Conservation, also manages soil conservation through terracing, drainage and irrigation (REMA 2009a; GOR 2010d).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Following the adoption of the 2004 Water Policy, the government has undertaken a significant number of actions to address the identified challenges and gaps. A Water Law (Law No. 62/2008 of 10/09/208 Putting in Place the Use, Conservation, Protection and Management of Water Resources Regulations) was enacted in 2008, and the governmental bodies responsible for water resource management have been restructured. In addition, in 2011, the government replaced its 2004 policy with the National Policy for Water Resources Management (GOR Water Resources Policy 2011).

The government has implemented several projects addressing specific water resource issues. The World Bank-supported Integrated Management of Critical Ecosystems (IMCE) Project assists farmers in four selected wetland ecosystems (Rugezi, Kamiranzovu, Akagera and Rweru-Mugesera) to adopt sustainable agricultural intensification technologies that are designed to improve farmers’ livelihoods while protecting the rare biological resources of wetlands. The IMCE has resulted in the development of 53 Watershed Management Committees, four Watershed Management Plans, nine Community-based Management Plans of critical swamps, and several new legal instruments supporting improved wetlands governance. The project supported a national marshland inventory in 2008, resulting in the classification of certain wetlands for conservation, controlled exploitation, and cultivation. The project also included communication initiatives – including documentaries, promotional material, conferences and workshops, and Head of State speeches – designed to strengthen the education and the public awareness of wetlands’ international importance (REMA 2009b; GOR 2010c).

The government’s Decentralization and Environmental Management Project (DEMP) ran from 2009 to 2013, and was implemented by REMA with support of UNDP. The project was designed to strengthen the capacity of REMA and adopt collaborative planning and management of Lake Kivu watersheds and associated riverbanks. The project planted vegetation on about 80 percent of the shoreline of Lake Kivu and riverbanks feeding the lake. The project also provided households with improved cooking stoves, introduced rainwater harvesting and run-off control technologies, and designed a resettlement program for people living within 50 meters of Lake Kivu’s shoreline (REMA 2009c; UNDP 2007).

The government is developing and rehabilitating water infrastructure, including constructing 13 new water tanks to supply water to Kigali, Rubavu, and Ruhango. The government partnered with UN-Habitat on a project to develop connections for poor households and is rolling out the project in Kigali, Kusororo and Jabana. The government is also renovating several water treatment plants, rehabilitating water sources and building additional infrastructure such as piping and water points. The Government has also created integrated water resources management initiatives to “maximize the resultant economic and social welfare without compromising the sustainability of ecosystems” (RWASCO 2010; The New Times 2014).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The African Development Bank has been a lead donor in the water and sanitation sector. The Bank’s Rural Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Programme (PNEAR I and II) (2009-2013) covered 15 districts in three Rwandan provinces (North, West and South). As of 2013, the programme had, in addition to sanitation activities, supplied storm water harvesting reservoirs constructed in village public infrastructures, created 153 km of drinking water supply networks, constructed 1,000 drinking water supply sources, and trained and supported borehole driller and private operators on maintenance of water facilities and complex water supply systems (AfDB 2013).

In 2014 the Government of Rwanda and AfDB signed a US$ 70 million agreement to improve access to drinking water, sanitation and hygiene in Africa. The funds for this “Kigali Action Plan” will be hosted by the Government of Rwanda and the African Union.

USAID supported the Integrated Water Security Program (RIWSP) (2011-2016) which was designed to implement the transformations necessary effectively improve water resource management in the country and to address future challenges (USAID 2013). It adopts an integrated approach to addressing water, sanitation and health, food security and climate related issues. The RIWSP project worked to improve sustainable management of water quantity and quality in order to create positive impacts on health, food security and resilience to climate change with a focus on vulnerable populations in targeted catchment areas.

The Government of Rwanda and the Howard G. Buffet Foundation signed a US$ 24 million partnership to development irrigation infrastructure in Kirehe (The New Times 2015b).

The World Bank is funding a five-year (2011-2015), US$ 76.3 million Land, Husbandry, Water Harvesting, and Hillside Irrigation Project. The project is designed to increase the productivity and commercialization of hillside agriculture in target areas through control of water resources. Project components include activities to develop the capacity of individuals and institutions for improved hillside land husbandry and water harvesting, and the provision of the necessary hardware for hillside intensification. The World Bank also funded a six-year (2001-2007) Rural Water and Sanitation Project that helped provide water access to about 510,000 people and constructed and rehabilitated water infrastructure (World Bank 2009b; World Bank 2008; World Bank 2011).

IFAD’s US$ 3.1 million Kirehe Community-Based Watershed Management Project (2009-2016) aims to increase links between farmers, markets and agricultural intensification programs through irrigation schemes.

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Approximately 18-19 percent of Rwanda is classified as forestland. The forests include Afro-montane ecosystems concentrated in the northwestern and southwestern regions, including mountain rainforests; lowland forests, savanna, and woodlands occur throughout much of the western and central regions of the country. The country has a limited amount of primary (old growth) forest (about 7,000 hectares); other naturally regenerated natural forest accounts for about 62,000 hectares. Planted forests make up the balance and largest percentage of forestland. Rwanda added about 162,000 hectares of forest between 1990-2005, resulting in a total increase in forest area between 2000-2005 at an estimated annual rate of 7.7 percent (World Bank 2009a; Mongabay 2010; REMA 2009a; WBDI).

Rwanda lies at the center of the Albertine Rift, considered Africa’s most biologically diverse area. Rwanda’s forests are home to 97 species of mammals, which make up 40 percent of the continent’s mammal species, including mountain gorilla and giant pangolin. Rwanda also has 1,061 species of birds, 293 species of reptiles and amphibians, and almost 6,000 species of higher plants. The forests provide the human population with timber and fuelwood, game and fish, medicinal plants, fodder, honey, fruits, tree seeds, essential oils, handicraft material, mushrooms, ornamental plants, and support for income-generating activities such as beekeeping and ecotourism (REMA 2009a; Mongabay 2010).

Seventy-nine percent of Rwanda’s forests are publicly owned and 21 percent are privately owned. Rwanda has four types of protected areas: (1) national parks (Akagera, Nyungwe and Volcanoes National Park); (2) forest reserves (Gishwati, Iwawa Island, and Mukura reserves); (3) forests of cultural importance (Buhanga forest); and (4) wetlands of global importance (Rugezi-Bulera-Ruhondo wetland complex). Some forests without protected status but with cultural importance include the Busaga forest in Muhanga district and other remnants of natural forest countrywide (REMA 2009a).

Although Rwanda has been gaining in forestland through reforestation and afforestation efforts, it has lost substantial amounts of forestland (an estimated 1.3 percent per year since 1960, 162,000 hectares since 1990), primarily as a result of encroachment for settlement and cultivation. During the years of conflict, forest service staff lost their jobs creating a void in enforcement, and war-displaced people cut down or damaged many forest plantations. Both plantation and natural forestland were used for resettlement of refugees. The country’s forests continue to be threatened by the pressure on land and the attendant expansion of cultivated areas. Forests are also threatened by the population’s dependence on fuelwood and charcoal for energy. An estimated 90 percent of the population relies on wood for heating and cooking. Illegal logging and fire also account for forest loss (REMA 2009a; Musahara 2006; FAO 2006; Mongabay 2010).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The primary legislation governing the forest sector in Rwanda is Law No. 47/2013 of 28/06/2013 Determining the Management and Utilisation of Forests in Rwanda. The law applies broadly to all types of forest, all tree species, all persons who either possess, process or use forest products and to all issues related to sustainable forest management. According to the law the government will prepare a 10-year forest management plan and large private production forests must also submit management plans for approval by the appropriate district. The law sets out a licensing scheme for the use of forest products and, interestingly, the law gives to those people living near and using forests the duty to conserve the resource and protect it from damage. Local authorities also are provided with responsibility to conserve, protect and develop forest resources, in accordance with the law (GOR Forest Law 2013).

In 2011 the government issued its National Forestry Policy, which aligns with Vision 2020 and emphasizes the important role that the forestry sector plays in supporting livelihoods in the country, in protecting watersheds and hence, supporting agriculture and energy needs. The Forestry Policy seeks to address concerns related to: increasing pressures on and competition for land for various uses; low yields on man-made forests; limited private sector investment in the sector; the need for value addition to forest products; mature and degraded forests; and, the country’s dependence on imports to supply industrially processed forest products (GOR Forestry Policy 2010f). The Forestry Policy also highlights the need to strengthen local participation in forest management to improve conservation and biodiversity outcomes.

TENURE ISSUES

Under the 2013 Forest Law, that forests may be owned by either the state, a district or by a private individual. State forests may be protected or used for production or research and include national parks, forests along the shores of rivers and lakes and some isolated trees. District forests may be production planted forests or those forest designed to maintain and safeguard the environment. State forests may be re-categorized based on an order of the Minister. Private forests may be small (not exceeding 2 ha.) production planned forests or large production planned forests (GOR Forest Law 2013). The law gives to the government the right to suspend forest harvesting to improve forest management, to allow for regeneration of forests and to conserve the environment and/or biodiversity.

The law emphasizes protection efforts related to state forests including by creating buffer zones around tree species of interest, protecting against forest fires, identifying protected trees, and creating inventories of forests. District forests may be managed by individuals, associations, companies, cooperatives or NGOs. District Councils grant these rights to selected entities (GOR Forest Law 2013). The law creates a license scheme for forest clearance, harvesting, transportation, forest product sale, the import or export of forest plants and trade in forest products or forestry seeds. Carbon market services are subject to review by the Rwanda Natural Resources Authority (RNRA).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Natural Resources (MINIRENA) has overall authority for the country’s forestland and resources. The Forestry and Nature Conservation Department (FNCD), which sits within The Rwanda Natural Resources Authority, has several responsibilities, including: (1) the design of policies and strategies relating to forestry and promoting agroforestry, (2) advising the Government on policies, strategies and legislation relating to forest management, (3) preparing national reforestation and forest management programs, (4) ensuring the management and use of public forest resources and (5) conducting forest-relevant research activities and disseminating research findings, among others (RNRA).

In 2005, Rwanda created the Designated National Authority (DNA), which is within REMA. DNA, which operates through a Permanent Secretariat and is supported by a Steering Committee and Technical Committee, was created to manage the country’s carbon projects, including coordinating Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects and voluntary carbon market (VCM) projects (REMA 2009d; REMA DNA).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Rwanda is a member of the Central African Forest Commission (COMIFAC), the regional body in charge of forests and environmental policy, coordination and harmonization, with the objective to promote the conservation and sustainable management of the Congo Basin’s forest ecosystems. COMIFAC is the primary authority for decision-making and coordination of sub-regional actions and initiatives. Rwanda is also a member of the Congo Basin Forest Partnership, which is a voluntary multi- stakeholder initiative that brings together the 10 member states of the COMIFAC, donor agencies, international organizations, NGOs, scientific institutions, and representatives from the private sector (CARPE 2010).

The government’s Protected Areas Biodiversity (PAB) Project (2006-2011) operated in Nyuajwe and Volcanoes national parks. The $13 million project was supported by UNDP and included components to: (1) support the development of national laws, collaborative frameworks, and capacity of central-level staff; (2) support development of local capacity for planning and co-management of forests and development of activities on adjacent land; and support for development of adaptive management capacity to assure long-term biodiversity preservation (UNDP 2010).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The Africa Forest Forum is funded by Sweden and Switzerland, and is aimed at supporting African stakeholders in strengthening the role of Africa’s forest and trees to adapt to climate change. Rwanda is one of twenty-three countries benefiting from this program, which is valued at US $9.2 million, and will run through December 2017 (Global Donor Platform for Rural Development).

The Government of Rwanda, in partnership with the Secretariat of the UN Forum on Forests and the International Union for Conservation of Nature, aim to achieve a “country-wide reversal” of social, water and land degradation by 2035 through the Rwanda Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (IUCN 2011).

Until 2015, USAID had two projects supporting the conservation of forestland in Nyungwe National Park. These projects developed a Protected Area Concession Management Policy, rehabilitated tourism infrastructure and training community cooperatives to maintain the trail system, supported six cooperatives to develop ecotourism products, developing the capacity of park guides, and promoted the ranger-based monitoring system.

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Rwanda has deposits of gold and concentrations of columbium (niobium), tantalum, tin, tungsten, cement, and small quantities of natural gas, beryllium, kaolin, and peat. The country also has deposits of precious stones, including sapphire, tourmaline, topaz, amethyst, opal, and agate. Historically, the mining sector has been small in both size and method; in 2007, the mining and quarrying sector accounted for less than 0.8 percent of GDP. However, the sector makes a substantial contribution to export revenue: in 2014, the sector accounted for 46.5 percent of export earnings. The mining sector is currently on track to meet the target of producing US$ 400 million mineral exports by 2017/2018. Investment, particularly in cassiterite tin production, has been increasing since 2004. Cassiterite, which is used to produce tin cans, is mined in 26 of Rwanda’s 30 districts. In 2012, Rwanda was responsible for 12 percent of the world’s tantalum production, and in the same year the production of tantalum increased by 146 percent. Increased activity in the sector is attributed to the entry of new producers. Foreign companies have licenses to explore for gold, nickel, cobalt, platinum, and copper (Yager 2010; REMA 2009a; Mukaaya 2009; IFC 2006; USDOS 2010; World Bank 2009a; The New Times 2015).

In 2010 about 35,000 people worked as small scale and artisanal miners in Rwanda and the subsector accounted for about half the mining exports in 2008. The government predicts an increase in export earnings from US$ 158 million in 2011 to US$ 400 million in 2017/2018. In 2014, the World Bank reported that the value of mining exports had reached US$ 225, which is more than half-way to the 2017 target (World Bank, 2014). Larger scale mining operations were conducted by the state since the 1980’s but were largely privatized by 2008. Foreign companies increasingly dominate the industry, including Gatumba Mining (South Africa), Bay View Group (U.S.), and Rwanda Mining (Germany). The Government holds a 50 percent share in Rutongo Mines Ltd., a 49 percent share in Gatumba Mining Concession Ltd. and owns Kibuye Poer 1 Ltd. (Mukaaya 2009; Yager 2010; GOR Mining Policy 2009; Rwandan Development Board).

Mining operations have, however, been responsible for environmental degradation in several areas of the country. Small and artisanal miners of gold and other minerals have settled in forests, clearing forestland for camps, depleting forest resources, and creating mineral waste. In other areas, water draining from mining operations has polluted the Nyabarongo, Sebeya, and Nyabugogo rivers with clay and sand sediment (REMA 2009a). The Ministry of Natural Resources suspended mining operations working in the area around the River Sebeya in the western province in 2012 (AllAfrica 2012).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Mining Sector Policy, which was released in 2009, was later updated in 2010. The policy has five pillars: (1) strengthen the enabling legal, regulatory, and institutional environment; (2) develop targeted investment and fiscal and macro-economic policies; (3) improve sector knowledge, skills, and use of best practices; (4) raise productivity and establish new mines; and (5) diversify into new products and increase value addition (GOR Mining Policy 2009; GOR Mining Policy Update 2010e).

In 2014, the Government of Rwanda adopted a new Mining Law (Law N°13/2014 on Mining and Quarry Operations), which was designed to streamline the industry and remove ambiguities of previous laws.

The biggest change in the new law is that it allows for a range of mineral license periods (between 2 and 25 years), customizable based on the capacity and needs of the applicant. The law also allows for artisanal licenses. Further, the Government is in the process of developing a mining cadastre that would provide information on all licenses and locations of mining activities. Prior to the passage of the new law, Rwanda’s Law on Mining and Quarry Exploitation from 2008 governed prospecting, search, exploitation, purchase, stocking, handling, transport, and commercialization of transferable substances other than hydrocarbon and including quarry products (GOR Mining Law 2008; GOR Law on Mining and Quarry Operations 2014; AllAfrica 2014).

A number of ministerial orders (on mineral license applications, types of mines, exporting samples, etc.) also exist to guide the nature of activity in the sector.

TENURE ISSUES

Ownership rights over mineral and quarry products vests in the Republic of Rwanda and not in the surface owners, with the objective of furthering the social and economic development of the nation. The Mining Law recognizes the following:

- All mining and exploration activities, whether artisanal and small-scale or large scale are governed by the law and its licensing provisions;

- Mining activities include exploration, mining, purchase, sale, stocking, processing, transport and marketing of minerals and quarry products as well as radioactive minerals;